George Washington/Lansdowne Portrait, Oil on Canvas, H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

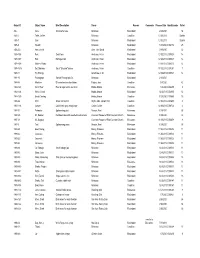

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Woodlawn Historic District in Fairfax Co VA

a l i i Woodlawn was a gift from George Washington In 1846, a group of northern Quakers purchased n a i r g to his step-granddaughter, Eleanor “Nelly” the estate. Their aim was to create a farming T r i e Custis, on her marriage to his nephew Lawrence community of free African Americans and white V , TION ag A y t V i t Lewis. Washington selected the home site settlers to prove that small farms could succeed r e himself, carving nearly 2,000 acres from his with free labor in this slave-holding state. oun H Mount Vernon Estate. It included Washington’s C ac x Gristmill & Distillery (below), the largest producer The Quakers lived and worshipped in the a f om Woodlawn home until their more modest r t of whiskey in America at the time. o ai farmhouses and meetinghouse (below) were F P Completed in 1805, the Woodlawn Home soon built. Over forty families from Quaker, Baptist, TIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESER became a cultural center. The Lewises hosted and Methodist faiths joined this diverse, ”free- many notable guests, including John Adams, labor” settlement that fl ourished into the early Robert E. Lee and the Marquis de Lafayette. 20th century. TESY OF THE NA COUR t Woodlawn became the fi rst property c of The National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1951. This private non- ri profi t is dedicated to working with t communities to save historic places. s i When construction of Route 66 threatened the nearby Pope-Leighey House (below), designed by renowned D architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the c National Trust relocated this historic home to Woodlawn. -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

Mount Rushmore

MOUNT RUSHMORE National Memorial SOUTH DAKOTA of Mount Rushmore. This robust man with The model was first measured by fastening a his great variety of interests and talents left horizontal bar on the top and center of the head. As this extended out over the face a plumb bob MOUNT RUSHMORE his mark on his country. His career encom was dropped to the point of the nose, or other passed roles of political reformer, trust buster, projections of the face. Since the model of Wash rancher, soldier, writer, historian, explorer, ington's face was five feet tall, these measurements hunter, conservationist, and vigorous execu were then multiplied by twelve and transferred to NATIONAL MEMORIAL the mountain by using a similar but larger device. tive of his country. He was equally at home Instead of a small beam, a thirty-foot swinging on the western range, in an eastern drawing Four giants of American history are memorialized here in lasting granite, their likenesses boom was used, connected to the stone which would room, or at the Court of St. James. He typi ultimately be the top of Washington's head and carved in proportions symbolical of greatness. fied the virile American of the last quarter extending over the granite cliff. A plumb bob of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th was lowered from the boom. The problem was to adjust the measurements from the scale of the centuries. More than most Presidents, he and he presided over the Constitutional Con model to the mountain. The first step was to locate On the granite face of 6,000-foot high knew the West. -

National US History Bee Round #1

National US History Bee Round 1 1. This group had a member who used the alias “Robert Rich” when writing The Brave One and who had previously written the anti-war novel Johnny Get Your Gun. This group was vindicated when member Dalton Trumbo received a credit for the movie Spartacus. Who were these screenwriters cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to testify before the anti-Communist HUAC? ANSWER: Hollywood Ten 052-13-92-01101 2. This man is seen pointing to a curiously bewigged child in a Grant Wood painting about his “fable.” This man invented a popular story in which a father praises the “act of heroism” of his son when the latter insists “I cannot tell a lie” after cutting down a cherry tree. Who is this man who invented numerous stories about George Washington for an 1800 biography? ANSWER: Parson Weems [or Mason Locke Weems] 052-13-92-01102 3. This building is depicted in Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. This building is where James Wilson proposed a compromise in a meeting convened after the Annapolis Convention suggested revising the Articles of Confederation. What is this Philadelphia building, the site of the Constitutional Convention? ANSWER: Independence Hall [or Old State House of Pennsylvania] 052-13-92-01103 4. This event's completion resulted in Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot's assassination by dissidents. This event was put into action after the Treaty of New Echota was signed. This event began at Red Clay, Tennessee, and many participants froze to death at places like Mantle Rock. -

Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition

In the Shadow of His Father: Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition URING His LIFETIME, Rembrandt Peale lived in the shadow of his father, Charles Willson Peale (Fig. 8). In the years that Dfollowed Rembrandt's death, his career and reputation contin- ued to be eclipsed by his father's more colorful and more productive life as successful artist, museum keeper, inventor, and naturalist. Just as Rembrandt's life pales in comparison to his father's, so does his art. When we contemplate the large number and variety of works in the elder Peak's oeuvre—the heroic portraits in the grand manner, sensitive half-lengths and dignified busts, charming conversation pieces, miniatures, history paintings, still lifes, landscapes, and even genre—we are awed by the man's inventiveness, originality, energy, and daring. Rembrandt's work does not affect us in the same way. We feel great respect for his technique, pleasure in some truly beau- tiful paintings, such as Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801: National Gallery of Art), and intellectual interest in some penetrating char- acterizations, such as his William Findley (Fig. 16). We are impressed by Rembrandt's sensitive use of color and atmosphere and by his talent for clear and direct portraiture. However, except for that brief moment following his return from Paris in 1810 when he aspired to history painting, Rembrandt's work has a limited range: simple half- length or bust-size portraits devoid, for the most part, of accessories or complicated allusions. It is the narrow and somewhat repetitive nature of his canvases in comparison with the extent and variety of his father's work that has given Rembrandt the reputation of being an uninteresting artist, whose work comes to life only in the portraits of intimate friends or members of his family. -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success. -

Mount Vernon Distillery Project: of Workers and Race

kelly UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research XIII (2010) Mount Vernon Distillery Project: Of Workers and Race Elizabeth Kelly Faculty Sponsors: Timothy McAndrews and David Anderson, Department of Sociology and Archaeology ABSTRACT The domestic artifacts of the Mount Vernon distillery site offer data on the lives of white workers. In comparing the domestic glass and ceramic artifacts of the distillery with comparable glass and ceramic data found at the slave site House for Families, the similarities and differences between the two groups can be seen. The artifact comparison may make it possible to determine if slave workers lived at the distillery along with the white workers. The artifact comparison showed that slaves and white workers were similar in being limited by their means. The existence of slave workers living at the distillery could not be determined at this time; however, potential areas for future analysis were presented. INTRODUCTION Historical archaeology is a discipline that has seen a shift in its focus over the years. The original interest of historical archaeology lay with the leaders of America. Archaeologists and historians studied and researched primarily the men who shaped and developed America. During the Civil Rights movement and other social movements of the 60's and 70's, historical archaeologists changed their focus. While there is still a strong interest in significant historical figures, there is a strong interest in historical archaeology concerning women, children, and slaves. This grouping had previously been neglected but was now the forefront of interest. Despite this focus on the less powerful of society, I have still found there to be a significant gap in research. -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives . -

George Washington Nelson Katarina Wonders

Prisoner of War: George Washington Nelson Katarina Wonders George Washington Nelson, affectionately known as Wash, was the nephew of Long Branch Plantation owners Hugh M. and Adelaide Nelson, a University of Virginia alumnus, and a Captain in the Confederate Army. Additionally, he was also one of many men captured and imprisoned during the Civil War. George and his companion Thomas Randolph were captured by Union soldiers on October 26th, 1863 in Millwood, VA while eating dinner.1 This domestic capture was the first of many oddities during George’s time as a Prisoner of War, since most soldiers were typically captured during, or as a result of, battle. George’s experiences as a POW demonstrate the common sufferings of men in Union prisons, while also allowing for a unique comparison between locations, as most prisoners did not move around nearly as much as George. Recounting his experiences as a POW, George wrote a brief narrative just over 10 years after his exchange on June 13th, 1865. The first night of his imprisonment was spent at Nineveh, Virginia under Captain Bailey. Wash makes a special note to credit Bailey for his immense kindness during their short period of time together. In Nineveh, the Captain lent George his gloves, and in Strasburg the next evening, Bailey gave the men a “first-rate supper” and tobacco before handing them off to the next set of Union men in Harper’s Ferry.2 The night spent in the “John Brown Engine House” was the first of Wash’s experience in a Union prison. He describes it as having “no beds, no seats, and the floor and walls were alive with lice.”3 After that night, the men were sent to Wheeling, West Virginia, where they found relatively nicer living conditions, but were soon sent to Camp Chase in Ohio only two or three nights later. -

Portraits by Gilbert Stuart

PORTRAITS BY JUNE 29 TO AUGUST l • 1936 AT THE GALLERIES OF M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY NEWPORT RHODE ISLAND As A contribution to the Newport Tercentenary observation we feel that in no way can we make a more fitting offering than by holding an exhibition of paintings by Gilbert Stuart. Nar- ragansett was the birthplace and boyhood home of America's greatest artist and a Newport celebration would be grievously lacking which did not contain recognition of this. In arranging this important exhibition no effort has been made to give a chronological nor yet an historical survey of Stuart's portraits, rather have we aimed to show a collection of paintings which exemplifies the strength as well as the charm and grace of Stuart's work. This has required that we include portraits he painted in Ireland and England as well as those done in America. His place will always stand among the great portrait painters of the world. 1 GEORGE WASHINGTON Canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Painted, 1795. This portrait of George Washington, showing the right side of the face is known as the Vaughan type, so called for the owner of the first of the type, in contradistinction to the Athenaeum portrait depicting the left side of the face. Park catalogues fifteen of the Vaughan por traits and seventy-four of the Athenaeum portraits. "Philadelphia, 1795. Canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Bust, showing the right side of the face; powdered hair, black coat, white neckcloth and linen shirt ruffle. The background is plain and of a soft crimson and ma roon color. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting.