Ayr Choral Union 1876-2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Celebration of Heritage

Opening Gala A Celebration of Heritage Mise Éire (Orchestral Suite) I Roisín Dubh II Boolavogue III Roisin Dubh/Druim Fhionn Donn Dílis IV Sliabh na mBan V Roisín Dubh Seán Ó Riada (1931-71) Cornucopia for Horn and Orchestra (1969/70) Prelude - Rondo In February of this year, Cork (and indeed, Ireland) lost one of the most intelligent and charismatic musicians to ever grace our shores. Aloys Fleischmann (1910-92) Alan Cutts had a huge influence on the education of literally hundreds of musicians - young and old - and he dedicated his time and expertise in the most humble and selfless manner imaginable. Intimations of Immortality for Tenor, Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 29 His rich wealth of knowledge was matched by his modesty and those of us who were lucky enough to study with and learn from him - be it Gerald Finzi (1901-56) in a junior choir or amateur orchestra; as a BMus or MA student at the Cork School of Music; as a member of Madrigal ’75, Wexford Opera Chorus, Irish Youth Choir, Fleischmann Choir; or as part of his many other activities including his appearances at the Cork International Choral Festival - will never forget his wisdom and charm. Cormac Ó hAodáin (French Horn) All of us on stage tonight wish to dedicate this concert to the memory Robin Tritschler (Tenor) of our friend, mentor and colleague, Alan. He is sorely missed but will forever be in our thoughts. Fleischmann Choir Cork School of Music Symphony Orchestra The 2015/2016 season of the Fleischmann Choir is also dedicated Maria Ryan (Leader) to Tadge O’Mullane and James Stevens. -

A Festival of Fučík

SUPER AUDIO CD A Festival of Fučík Royal Scottish National Orchestra Neeme Järvi Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Photo Music & Arts Lebrecht Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík (1872 – 1916) Orchestral Works 1 Marinarella, Op. 215 (1908) 10:59 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – Andante – Adagio – Tempo I – Allegro vivo – Più mosso – Tempo di Valse moderato alla Serenata – Tempo di Valse – Presto 2 Onkel Teddy, Op. 239 (1910) 4:53 (Uncle Teddy) Marche pittoresque Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Marcia da Capo al Fine 3 Donausagen, Op. 233 (1909) 10:18 (Danube Legends) Concert Waltz 3 Andantino – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo I – Più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo di Valse risoluto – 3:06 4 1 Tempo di Valse – 1:48 5 2 Con dolcezza – 1:52 6 3 [ ] – 1:25 7 Coda. [ ] – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo di Valse 2:08 8 Die lustigen Dorfschmiede, Op. 218 (1908) 2:34 (The Merry Blacksmiths) March Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 9 Der alte Brummbär, Op. 210 (1907)* 5:00 (The Old Grumbler) Polka comique Allegro furioso – Cadenza – Tempo di Polka (lentamente) – Più mosso – Trio. Meno mosso – A tempo (lentamente) – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – [Cadenza] – Più mosso 4 10 Einzug der Gladiatoren, Op. 68 (1899) 2:36 (Entry of the Gladiators) Concert March for Large Orchestra Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Grandioso, meno mosso, tempo trionfale 11 Miramare, Op. 247 (1912) 7:47 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – Andante – Adagio – Allegro vivace 12 Florentiner, Op. 214 (1907) 5:20 Grande marcia italiana Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 13 Winterstürme, Op. -

Alan Rawsthorne Violin and Piano Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alan Rawsthorne Violin And Piano mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Violin And Piano Country: UK Released: 1963 Style: Neo-Classical, Modern, Serial MP3 version RAR size: 1193 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1769 mb WMA version RAR size: 1679 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 993 Other Formats: MP1 VQF FLAC MOD DXD DTS AIFF Tracklist A-1 Sonata For Violin And Piano-1959 A-2 Colloquy For Violin And Piano-1960 B Twelve Studies For Piano Op.38, 1960 Companies, etc. Record Company – Argo Record Company Limited Credits Composed By – Alan Rawsthorne (tracks: A-1), Peter Racine Fricker (tracks: B), Thea Musgrave (tracks: A-2) Piano – Lamar Crowson Violin – Manoug Parikian (tracks: A-1, A-2) Notes ARGO RECORD COMPANY LIMITED 113 FULHAM RD LONDON S3 Recorded in Association with the British Council. Cover Laminated with "Clarifoil" Dark Green Label...Deep Groove both sides. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Alan Rawsthorne, Thea Alan Rawsthorne, Thea RG 328 Musgrave, P.Racine Musgrave, P.Racine Fricker* - Argo RG 328 UK 1963 Fricker* Violin And Piano (LP, Mono) Related Music albums to Violin And Piano by Alan Rawsthorne Fauré, The Choir Of St. Johns College, Cambridge • The Academy Of St. Martin In The Fields • Benjamin Luxon • Jonathan Bond • George Guest - Messe De Requiem Op.48 / Cantique De Jean Racine Op.11 Denes Zsigmondy, Anneliese Nissen - Brahms Sonata For Violin And Piano Op. 108 And Op. 100 Senofsky - Vanden Eynden, Johannes Brahms, Richard Strauss - Sonata For Violin And Piano N°2 - Opus 100 / Sonata For Violin And Piano - Opus 18 Beethoven, Mieczyslaw Horszowski, Sandor Vegh, Pablo Casals - Trio For Piano, Violin, And Cello No. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

12:00:00A 00:00 Lunes, 29 De Julio De 2019 12A NO

*Programación sujeta a cambios sin previo aviso* LUNES 29 DE JULIO 2019 12:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 29 de julio de 2019 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00a 11:27 Con aires veracruzanos (2010) p/clarinete y guitarra Mauricio Hernández Monterrubio (1972-) Ensamble Due Voci 12:11:27a 23:58 Suite no.4 en Si Bem.May. R.109-117 Gottlieb Muffat (1690-1770) Borbala Dobozy-clavecín 12:35:25a 20:29 Nipson (1998) p/contratenor y 5 violas da gamba John Tavener (1944- ) Ens. Fretwork (violas da gamba) Michael Chance, contratenor 12:55:54a 00:50 Identificación estación 01:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 29 de julio de 2019 1AM NO - Nocturno 01:00:00a 10:13 Concierto p. violín y orq. op.9 no.4 en Si LaMay. Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751) Claudio Scimone I solisti Veneti Astorre Ferrari-violín 01:10:13a 36:59 Sinfonía no.3 en Mi May.op.51 Max Bruch (1838-1920) Manfred Honeck Orquesta del Estado Húngaro 01:47:12a 08:46 Totus Tuus Henryk Gorecki (1933-2010 ) Coro de la Capilla del colegio 01:55:58a 00:50 Identificación estación 02:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 29 de julio de 2019 2AM NO - Nocturno 02:00:00a 14:20 Concierto p/flauta y cuerd. en Re May. Gimo291 Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) Giorgio Bernasconi Academia instumental italiana Marzio Conti, flauta 02:14:20a 26:03 Caballos de vapor ("Horse power") Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) Eduardo Mata Sinfónica de Londres 02:40:23a 15:50 \Rapsodia India Frederic Hymen Cowen (1852-1935) Adrian Leaper Filarmónica del estado checoeslovaco 02:56:13a 00:50 Identificación estación 03:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 29 de julio de 2019 3AM NO - Nocturno 03:00:00a 14:22 Quinteto p/2 flautas, violín, viola y cello op.7 no.6 en Sol May. -

CUL Keller Archive Catalogue

HANS KELLER ARCHIVE: working copy A1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49 A1/1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49: independent work This section contains all Keller’s unpublished manuscripts dating from the 1940s, apart from those connected with his collaboration with Margaret Phillips (see A1/2 below). With the exception of one pocket diary from 1938, the Archive contains no material prior to his arrival in Britain at the end of that year. After his release from internment in 1941, Keller divided himself between musical and psychoanalytical studies. As a violinist, he gained the LRAM teacher’s diploma in April 1943, and was relatively active as an orchestral and chamber-music player. As a writer, however, his principal concern in the first half of the decade was not music, but psychoanalysis. Although the majority of the musical writings listed below are undated, those which are probably from this earlier period are all concerned with the psychology of music. Similarly, the short stories, poems and aphorisms show their author’s interest in psychology. Keller’s notes and reading-lists from this period indicate an exhaustive study of Freudian literature and, from his correspondence with Margaret Phillips, it appears that he did have thoughts of becoming a professional analyst. At he beginning of 1946, however, there was a decisive change in the focus of his work, when music began to replace psychology as his principal subject. It is possible that his first (accidental) hearing of Britten’s Peter Grimes played an important part in this change, and Britten’s music is the subject of several early articles. -

National Library of Ireland Nuacht

Number 38: Winter 2009 NEWS The Library’s latest exhibition, Discover your National Library: Explore, Reflect, Connect provides a unique opportunity for the public to view first-hand a representative selection of the Library’s holdings – the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of Irish documentary material numbering almost eight million items including maps, prints, drawings, manuscripts, photographs, books, newspapers and periodicals. Among the artefacts currently on display are rare manuscripts such as the Book of Maguaran dating from the Middle Ages and a deed signed by Sir Walter Raleigh. There are also curiosities such as a 1795 lottery ticket (we don’t know if it won), and more contemporary items such as a set of cigarette cards illustrated by Jack Yeats from the 1930s. 2009 marked the Bogs Commission bicentenary, an event which the exhibition celebrates by focusing on the achievements of the 18th century and early 19th century pioneers who managed to produce large and very detailed maps of Ireland’s bogs in the period before the advent of the Ordnance Survey. The effort to survey the bogs was driven by the need to see if it was feasible to grow crops such as corn or hemp on Ireland’s bogs, at a time when the English government was fighting the Napoleonic wars and suffering economic shortages. Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Throughout, the exhibition makes extensive use of digital media, with special features including a series of screened talks by the Library’s curators describing the significance or importance of certain exhibition items. -

Rsno.Org.Uk Rsno.Org.Uk/SEASON1516

2015:16 USHER HALL, EDINBURGH rsno.org.uk rsno.org.uk/SEASON1516 Subscribe SCOTLAND’S AND SAVE NATIONAL Save up to 35% when you subscribe to the Season! Simply choose a minimum of four concerts and you can start saving money. Book ORCHESTRA today using the pull-out booking form at the centre of the brochure. Celebrating 125 years of great music! Exclusive reception In 2016 the RSNO Subscribe to all eighteen Season concerts and you will receive an invitation to an exclusive reception with RSNO reaches an exciting Principal Timpanist Martin Gibson. milestone in its history – its 125th birthday! Since 1891 the Orchestra has enjoyed performing PETER OUNDJIAN BIRTHDAY BOYS: across Scotland and CONDUCTS CHORAL PROKOFIEV AND MASTERPIECES PORTER beyond with some of the We couldn’t celebrate 125 The RSNO isn’t alone years of great music without celebrating 125 years finest musicians of the the wonderful singers of the of glorious music. Sergei RSNO Chorus. Music Director Prokofiev and Cole Porter were day – and this Season we Peter Oundjian directs three also born in 1891 and so we’ll continue that tradition. large-scale choral masterpieces be sharing some of their finest throughout the Season. Make music with you across the Join us as we celebrate sure you don’t miss Mahler’s Season. Prokofiev’s Cinderella Resurrection Symphony, and Romeo and Juliet both our birthday and look Vaughan Williams’ Sea feature, and we’re especially Symphony and Beethoven’s thrilled that Nikolai Lugansky forward to another 125 Ninth Symphony Choral, which is joining us to perform all five brings the first half of our of Prokofiev’s piano concertos years of great music. -

National Library of Ireland NUACHT Leabharlann Náisiúnta Na Héireann IMPORTANT NOTICES and Thevenueisbuswell’S Hotel 20Th Centuryireland’.Lecturescommenceat7p.M

NEWS Number 15: Spring 2004 The Library will begin a new chapter of its history next June with the opening of a newly refurbished and enlarged exhibition facility in its Kildare Street premises. The inaugural exhibition, James Joyce and Ulysses at the National Library of Ireland, will mark the centenary of Bloomsday, that is 16 June 1904, the day on at the turn of the 19th century, for example, the central role of which the events described in Ulysses are supposed to have all kinds of music in the lives of Dubliners – and so also of the taken place. characters in Ulysses – as well as the provocative and often contradictory political propaganda of the period, whether it was of a The highlight of the exhibition will be the newly discovered national or a racist character – themes that Leopold Bloom and the Ulysses manuscripts that were recently acquired by the Library. Citizen confront in such a comic but yet poignant episode as The manuscripts, which are visually striking, document as ‘Cyclops’, will play a central role in the exhibition. completely as one could hope the creative process that produced Much of the material that will go on show is bright and colourful Ulysses, a process that visitors will be able to follow in an exciting belying the often black and white or sepia perception of way by means of digital technology. Joycean Dublin. The exhibition’s more general goal is to introduce and explain the The exhibition will appeal to a wide array of visitors including those significance of Ulysses, so there will be maps and timelines, as well who have never read Joyce and remain sceptical of all the talk of as character and plot databases. -

Download Booklet

570406bk USA 12/7/07 7:36 pm Page 5 8.570406 Royal Scottish National Orchestra British Piano Concerto Foundation Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being British Piano Concertos DDD granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Britain shares with the United States an extraordinary willingness to welcome and embrace the Europe’s leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include traditions of foreign cultures. Our countries comprise the world’s two greatest ‘melting pots’, and, as Sir John Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, a result, the artistic appreciation of our people has been possibly the most catholic and least nepotistic Neeme Järvi, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, in the world. This tradition is one that we may be extremely proud of. In the case of music, it is John who served as Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane certainly one of the reasons for my own initial inspiration to become a musician and to embrace as Denève was appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first Naxos recording, which couples Roussel’s Symphony many different styles and periods as reasonably possible in one lifetime. No. 3 with the complete ballet Bacchus et Ariane (8.570245) was released in May 2007. The orchestra made an Perhaps as a result of this very enviable virtue, however, we do have a tendency to underrate the GARDNER important contribution to the authoritative Naxos series of Bruckner Symphonies under the late Georg Tintner, and artistic traditions of our own wonderful culture. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

Troy My Trust in Things and Convert Me Into a Masterful Cynic

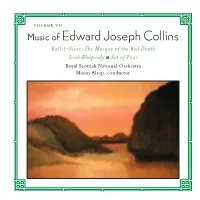

VOLUME VII Music of EdwardJoseph Collins Ballet~Suite: The Masque of the Red Death Irish Rhapsody ■ Set of Four Royal Scottish National Orchestra Marin Alsop, conductor Edward J. Collins ■ An American Composer by Erik Eriksson Composer and pianist Edward Joseph Collins was born on 10 November 1886 in Joliet, Illinois, the youngest of nine children. After early studies in Joliet, he began work with Rudolf Ganz in Chicago. In 1906, Collins traveled with Ganz to Berlin, where he enrolled in the Hochschule für Musik in performance and composition. Upon graduation, he made a successful concert debut in Berlin, winning positive reviews from several critics. When Collins returned to the United States in the fall of 1912, he toured several larger eastern cities, again winning strong reviews. After serving as an assistant conductor at the Century Opera Company in New York, he traveled again to Europe, to become an assistant conductor at the Bayreuth Festival, a position cut short by the outbreak of World War I. During that war, Collins rose from Private to Lieutenant. He served as an interpreter, received a citation Edward Collins, year and location for bravery, and entertained the troops as pianist. unknown. Upon return to Chicago, he began a career in teaching, joining the faculty of the Chicago Musical College. He later married Frieda Mayer, daughter of Oscar Mayer. Collins had co-authored Who Can Tell? in Europe near the end of WW I; the operetta was enjoyed in Paris by President Wilson. Collins continued composing on return to the USA. Two compositions submitted to a Chicago competition in 1923 were among the finalists, one the outright winner.