Overview of Current MPA Management Processes in Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales This Events Programme Is Brought To

West Glamorgan Local Group Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales This events programme is brought to you by the West Glamorgan The Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales Local Group consisting is part of the largest UK voluntary purely of volunteers. organisation dedicated to conserving the full range of the UK's habitats and species. West Glamorgan Group Committee The Trust covers a huge area from Chairman Mark Winder Cardiff & Caerphilly in the east Secretary Elizabeth May (retiring) to Ceredigion & Pembrokeshire in the west. Treasurer John Gale (retiring) Events Jo Mullett It cares for over 90 nature reserves Members Roy Jones including 4 islands. WEST GLAMORGAN Mervyn Howells LOCAL GROUP John Ryland Volunteering Opportunities PROGRAMME 2010 Neil Jones Stewart Rowden • Conservation Volunteers • Reserve & Assistant Wardens • Education Volunteers • Administration Volunteers Note: programme subject to change. We are always looking for new • Membership recruitment committee members so if you are Please confirm details interested please get in touch. Tel: 01656 724100 Book on all outdoor events. Website www.welshwildlife.org Non-members welcome. Conservation Work If you are interested in conservation work please contact Senior Wildlife Trust Officer Senior Officer: Paul Thornton Tel: 01656 724100 E mail: [email protected] INDOOR TALKS 14th Sept, AGM Living Landscapes & Seas 21st- 22nd May, 24 Hour Biodiversity Blitz A vision of conservation for the Wildlife Trust Celebrate International Biodiversity Day by Our indoor talks start 7.30pm prompt every of South & West Wales focusing on our local discovering & recording all the flora & fauna 2nd Tuesday of the month (except July & patch. observed in 24 hours! Sarah Kessell, Wildlife Trust of South & West City & County of Swansea August) at the Environment Centre, Pier Wales th Street, Swansea. -

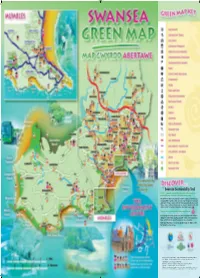

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA39 GOWER © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Penrhyn G ŵyr – Disgrifiad cryno Mae Penrhyn G ŵyr yn ymestyn i’r môr o ymyl gorllewinol ardal drefol ehangach Abertawe. Golyga ei ddaeareg fod ynddo amrywiaeth ysblennydd o olygfeydd o fewn ardal gymharol fechan, o olygfeydd carreg galch Pen Pyrrod, Three Cliffs Bay ac Oxwich Bay yng nglannau’r de i halwyndiroedd a thwyni tywod y gogledd. Mae trumiau tywodfaen yn nodweddu asgwrn cefn y penrhyn, gan gynnwys y man uchaf, Cefn Bryn: a cheir yno diroedd comin eang. Canlyniad y golygfeydd eithriadol a’r traethau tywodlyd, euraidd wrth droed y clogwyni yw bod yr ardal yn denu ymwelwyr yn eu miloedd. Gall y priffyrdd fod yn brysur, wrth i bobl heidio at y traethau mwyaf golygfaol. Mae pwysau twristiaeth wedi newid y cymeriad diwylliannol. Dyma’r AHNE gyntaf a ddynodwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig ym 1956, ac y mae’r glannau wedi’u dynodi’n Arfordir Treftadaeth, hefyd. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11 Erys yr ardal yn un wledig iawn. Mae’r trumiau’n ffurfio cyfres o rostiroedd uchel, graddol, agored. Rheng y bryniau ceir tirwedd amaethyddol gymysg, yn amrywio o borfeydd bychain â gwrychoedd uchel i gaeau mwy, agored. Yn rhai mannau mae’r hen batrymau caeau lleiniog yn parhau, gyda thirwedd “Vile” Rhosili yn oroesiad eithriadol. Ar lannau mwy agored y gorllewin, ac ar dir uwch, mae traddodiad cloddiau pridd a charreg yn parhau, sy’n nodweddiadol o ardaloedd lle bo coed yn brin. Nodwedd hynod yw’r gyfres o ddyffrynnoedd bychain, serth, sy’n aml yn goediog, sydd â’u nentydd yn aberu ar hyd glannau’r de. -

Oxwich Beach Walk Gower

Oxwich Beach Walk Gower Description: A lovely short walk on the sands of Oxwich Bay and the nature reserve behind, great for an evening stroll and then a pint at the Oxwich bay hotel. Distance covered: 2 miles Average time: 1.0 hours Terrain: Easy under foot and flat beach walk suitable for pushchairs except at high tide. Directions: Park your car at the large beach car park. Follow the beach to the East towards 3 cliffs bay in the distance. The shallow sloping beach is one of the most sheltered in Gower its great for water sports and safe for swimming. Back in 1911, the beach was actually the site of the first aeroplane flight in Wales by Mr E. Sutton in a Bleriot monoplane. In fact the sands continued to attract petrol heads for much of the first half of the 20 th century with many motorbike races speedway and speed trials held on the beach. After about a mile you will meet a small river, at this point bear left into the sand dune system and follow any of the paths which double back in the direction from which you have come. History: The sand dune system you are walking through is managed by the Countryside council for Wales . Prior to the area becoming a national nature reserve the dunes were extremely badly eroded. the northern part of the dunes was actually described by a local botanist as “a sandy waste devoid of life” the poor state was sue in part to extensive use by the American army and RAF for practice manoeuvres during world war two. -

Gwent-Glamorgan Recorders' Newsletter Issue 19

GWENT-GLAMORGAN RECORDERS’ NEWSLETTER ISSUE 19 AUTUMN 2018 Contents New opportunities for the growth and expansion of Mistletoe in 3 Gwent Porthkerry Country Park Wildflower Meadow Creation 4-5 Buglife Cymru’s Autumn Oil Beetle Hunt 6-7 Geranium Bronze in Creigiau 8 Bioluminescent plankton in Wales 9 The Brimstone Butterfly in Gwent 10-11 Exciting plant finds in Monmouthsire Vice-County 35 in 2018 12-13 Slow Moth-ing 14-15 SEWBReC Business Update 16 SEWBReC Membership & SEWBReC Governance 17 National Fungus Day 2018 18 Slime Moulds 18-19 2018 Encounters with Long-horned Bees 20-21 Wales Threatened Bee Report 22 SEWBReC News Round-up 23 Welcome to Issue 19 of the Gwent-Glamorgan Recorders’ Newsletter. As another recording season draws to a close for many species groups, it is in- teresting to look back at the summer’s finds throughout south east Wales. Whether it is a Welsh first (Geranium Bronze in Creigiau, pg 8), a phenomenon rarely seen in our temperate climate (Bioluminescent plankton in Wales, pg 9) or just taking the time to study something often overlooked (Slime Moulds, pg 18), the joys of discovery through wildlife recording is evident throughout this issue. It is also great to learn of the efforts being made to preserve and enhance biodi- versity by organisations such as Porthkerry Wildlife Group (Porthkerry Country Park Wildflower Meadow Creation, pg 4) and Buglife (Wales Threatened Bee Re- port, pg 22). Many thanks to all who contributed to the newsletter. I hope this newsletter will be an inspiration to all our recorders as the nights draw in and your backlog of summer recording beckons! Elaine Wright (Editor) Cover photo: Stemonotis fusca © Steven Murray. -

Christmas 2018

Ysgol Stanwell School Sporting Excellence School Productions Clubs & Activities Contents Greetings from the School School Calendar 2018/19 School Trips 2018/19 Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme Eco-Schools Healthy Schools Department News Year Group News 100% attendance pupils Greetings from the school Dear Parents and Carers, As we come to the end of a busy term, this edition of our school newsletter shows just a few examples of the talents, energy and generosity of our school community. I hope you enjoy it. Our greatest strength is our students and we are delighted that they have settled quickly into school life this term. Pupils continue, in all of their endeavours, to make an outstanding contri- bution to Stanwell’s vibrant learning community, within and outside of the classroom. I am hugely grateful to our outstanding staff team who have the strongest commitment to ensuring the best possible experiences for our young people, whether in lessons or through the extensive range of extra-curricular clubs, groups, trips and visits that they provide. Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you, our parents and carers, for all of your support of the school and for working in partnership with us during 2018. On behalf of all at Stanwell School, I wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Yours faithfully, Trevor Brown Headteacher School Announcements Parents and pupils are reminded that Tuesday 8th January will be the first day of the Spring term for pupils as Monday 8th January is an INSET day. The date of the 2018 PTA quiz will be Friday 25th January. -

Area 1 Development Control Committee

CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA NOTICE OF MEETING You are invited to attend a Meeting of the AREA 2 DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE At: Council Chamber, Civic Centre, SWANSEA On: Tuesday 20 December 2011 Time: 2.00p.m. Members are asked to contact John Lock (Planning Control Manager) on 635731 should they wish to have submitted plans and other images of any of the applications on this agenda to be available for display at the Committee meeting. AGENDA 1. Apologies for Absence. 2. Declarations of Interest To receive Disclosures of Personal and Prejudicial Interests from Members in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Conduct adopted by the City and County of Swansea. (NOTE: Members are requested to identify the Agenda Item /minute number/ planning application number and subject matter that their interest relates). 3. To approve as a correct record the Minutes of the meeting of the Area 2 Development Control Committee held on 22 November 2011. FOR DECISION 4. Town and Country Planning - Planning Applications:- (a) Items for deferral/withdrawal. (b) Requests for Site Visits. (c) Determination of Planning Applications. Patrick Arran Head of Legal, Democratic Services & Procurement 13 December 2011 Contact: Democratic Services 01792 636820 ACCESS TO INFORMATION LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1972 (SECTION 100) (AS AMENDED) (NOTE: The documents and files used in the preparation of this Schedule of Planning Applications are identified in the ‘Background Information’ Section of each report. The Application files will be available in the committee room for half an hour before the start of the meeting, to enable Members to inspect the contents) Item No. -

125841 Great-Little-Places.Pdf

The Great Little Places Guide 2021 Part of the Welsh Rarebits Collection Take me away Take 2021 Tel + 44 (0)1570 470785 Email [email protected] A unique collection of 36 small, personally Website little-places.co.uk run places to stay throughout Wales. H21007 GLP 2021 A_W.indd 1 29/03/2021 20:13 GREAT LITTLE PLACES Gift Vouchers Give an extra special GIFT this year. From country houses to boutique boltholes and cosy B&Bs, Great Little Places’ members are all different, but they offer the same thing – genuine Welsh hospitality. 02 The Great Little Places Guide 2021 H21007 GLP 2021 A_W.indd 2 29/03/2021 20:13 This year, why not treat a loved one to a gift experience at one of our unique venues by giving them a Great Little Places gift voucher towards an unforgettable stay? Monetary vouchers start 25100 Wherever and whenever you decide to visit, you’re guaranteed a warm Welsh welcome. Gift vouchers / Downloadable e-vouchers from £25 Gift Experiences from £100 For more information little-places.co.uk Email [email protected] Tel +44 (0)1570 470785 E-vouchers available for last minute presents. H21007 GLP 2021 A_W.indd 3 29/03/2021 20:13 WELCOME... OR AS WE SAY IN WALES – ‘CROESO’ Since we launched the scheme in 1994 we’ve travelled countless thousands of miles the length and breadth of Wales to seek out the very best small hotels, inns, farmhouses, restaurants with rooms and guest houses. GLPs are the kind of places in which we like to stay. -

Visit Swansea

Finding Out Swansea Tourist Information Centre Plymouth Street, Swansea SA1 3QG (01792 468321 *[email protected] Open all year National Trust Visitor Centre Coastguard Cottages, Rhossili, Gower, Swansea SA3 1PR (01792 390707 Open all year Image Credits and Copyrights Rock Climbing p5: Dynamic Rock Ltd, Useful Contacts Coasteering p12: Adventure Britain, Rhossili National Trust p14: NTPL/John Millar, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery p28: Powell Dobson Swansea Mobility Hire Architects, Pennard Golf Course p31: Swansea City Bus Station, VisitWales © Crown Copyright, Family p34: Plymouth Street, National Waterfront Museum, Mummy p35: Swansea SA1 3AR Swansea Museum, Beach Volleyball p42: (01792 461785 360 Beach and Watersports RNLI The Council of the City & County of Swansea www.rnli.org cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information in this brochure and accepts no responsibility for any error or Published by the City & County of Swansea misrepresentation, liability for loss, © Copyright 2015 disappointment, negligence or other damage caused by the reliance on the information contained in this brochure unless caused by This publication is available in the negligent act or omission of the Council. alternative formats. Contact Please check and confirm all details before Swansea Tourist Information booking or travelling. Centre (01792 468321. Swansea Bay Mumbles, Gower, Afan & The Vale of Neath Key to beach awards 0 6km Blue Flag and Seaside Award Seaside Award 0 3 miles This map is based on digital photography licensed from NRSC Ltd. © City and County of Swansea 2015 visitswanseabay.com Contents 02 Introduction 04 Adventure 13 Cycling 14 Discover 16 Dylan Thomas 18 Entertainment 19 Event Highlights 20 Fishing 20 Food & Drink 28 Galleries 30 Golf 32 Heritage 36 Horse Riding 37 Parks & Gardens 38 Shopping 41 Walking 42 Watersports & Swimming 47 Getting About Finding Out & Area Map (back cover) visitswanseabay.com 1 Introduction Make the most of your visit to Swansea Bay. -

Things to Do

2018/19 visitswanseabay.com Things to Do y a B a e ns #SeaSwa Swansea Bay Mumbles, Gower, Afan & The Vale of Neath DISCOVER YOUR GOWER adventure Visit the largest collection of holiday homes in Mumbles, Gower & Swansea Marina From peaceful retreats, to family fun, to energetic outdoor 45 YEARS adventures, we have the best holiday accommodation to OVERMANAGING suit your needs, all managed by Gower’s most experienced GOWER45 YEARS PROPERTIES locally-based agency. Visit our website or give us a call, one MANAGING GOWER PROPERTIES of our dedicated local team members will be happy to help. Key to beach awards 0 4km Blue Flag and Seaside Award 0 2 miles Seaside Award 01792 360624 Marina Blue Flag Award [email protected] 101 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea, SA3 4BN This map is based on digital photography licensed #hfhmoments from NRSC Ltd. © Swansea Council 2018 visitswanseabay.com Contents 04 Ahoy There! 05 Adventure 14 Cycling 14 Discover 17 Dylan Thomas 18 Entertainment 20 Events 22 Food & Drink 32 Galleries 34 Holiday Essentials 35 Golf 36 Heritage 39 Parks & Gardens 40 Shopping 42 Walking 43 Watersports & Swimming 47 Getting About 50 Play Safe Finding Out & Area Map (back cover) visitswanseabay.com 1 C A N O L F A N C E N T R E EXPERIENCES WORTH SHARING Outdoor team-building with impact Full day or half day experiences Visit our free, family- available Group size from friendly exhibition. Be a 6 upwards! Dylan Thomas Explorer and learn about our Down to Earth delivers remarkable experiences that wonderful wordsmith bring out the best in your group. -

96% UWTSD's Swansea Students

#From Higher Ed To Hired #From Higher We are proud of what our students achieve with us and what they go on to do after graduation, so we have gathered a few of their stories, and some employment data, to share with you. Here you will find Oscar-winning art school graduates and innovative Ed product designers, published poets and engineering experts on the fast track to success. UWTSD alumni are making a difference in many fields, from teaching and youth work to business, sport, the arts, health, higher education and more. Our former students speak of how the support they received helped them To in their careers. As well as providing a nurturing environment, the university embeds employability into its courses, brings employers in and sends students on internships in order to provide a practical preparation for working life alongside academic study. Hired Our dynamic and innovative approach includes Life Design, a four-step programme available to all UWTSD students, created to help you make the most of your time at university and to ensure you are ready for life in a rapidly changing world. UWTSD offers a range of entrepreneurship and employability enhancement opportunities by working with employers and community organisations to develop skills required for self-employment or for working in business. In addition, many of our academic courses include elements of work-based learning or live projects. We share our graduates’ stories under #FromHigherEdToHired on social media. Choose to study with us at UWTSD and we will be looking forward