Churches in Gower April 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Due to CV-19, It Is Not Going to Be Practical for the Community Council

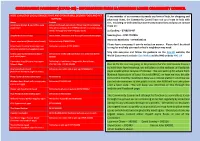

HERE IS A LIST OF LOCAL SERVICES THAT ARE OPEN OR WILL DELIVER FOOD AND PET If any member of our community needs any form of help, for shopping and SUPPLIES pharmacy items, the Community Council have set up a team to help with Name Contact this. It is being co-ordinated by 3 Community Councillors and you can contact Heronsway Garage & post office open Deliveries through volunteers. Please ring Cllr Jo Gooding them on: usual hours who will co-ordinate this 07989214487 (if no answer please leave a message and she’ll ring you back) Jo Gooding – 0798921487 Shepherds (fruit and veg) Don’t phone. Deliveries only through Facebook messenger. Sam Hughes – 07917704926 Moranda Matthews – 07903335154 Gower coast meat (Gower raised meat) Deliveries only 07939378084 Please leave a message if you do not get an answer. Please don’t be afraid Brian Davies Country Stores (Agri and Deliveries available 01792 875050 to ring for any help you need or feel a neighbour may need. domestic animal food suppliers) open Stay safe everyone and follow the guidance on the Gov.UK website, the Crofty supermarket (Grocery shop + Deliveries to Crofty and Llanrhidian min order £20 01792 post office) open 850258 Welsh Government website Gov.Wales and the NHS website NHS.UK Llanmadoc shop (Grocery shop) open Delivering to Landimore, Llangennith, Burry Green, 10am-1.00pm Cheriton only. 01792 386494 Due to CV-19, it is not going to be practical for the Community Council to hold their April meeting, we will place on the website or Facebook King’s Head pub closed Deliveries min order £25 or pick up 01792386212 (Please see Facebook page for menu) page anything that may be of interest. -

Dart18europeans

AUGUST 16TH - 22ND rt18euro da peans 2014 .org WELCOME CROESO A big warm welcome to one and all from The Mumbles Yacht Club and we hope you have a fantastic week both on and off the water. Our team has been working tirelessly for months to put this all together and I’m sure that it will be a memorable event for everyone involved. If you need, or are not sure of anything during your stay please don’t be shy - just ask, this whole week is part of all of our hols and is therefore meant to be fun and hassle free. May I just say a big thank you to the City and County of Swansea for their support, without which none of this would be possible, and also to ALL of our sponsors for their contributions enabling us to develop a packed programme both on and off the water. Welcome ashore... From peaceful retreats, to family fun, to energetic Again, Welcome and Enjoy. Visit the largest collection outdoor adventures, we have the best holiday of holiday homes in accomodation to suit your needs, all managed by Mumbles, Gower Gower’s most experienced locally-based agency. Chris Osborne Visit our website or give us a call. One of our Commodore & Swansea Marina dedicated local team will be happy to help. ( Dart 7256 ) OVER mumblesyachtclub.co.uk 2 Tel +44 (0) 1792 360624 | [email protected] | www.homefromhome.com 101 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea, SA3 4BN MUMBLES - the club that likes to say YES! special offer It was the Welsh Open Dart 18 Championships 2013. -

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas Would Have Known

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas would have known visitswanseabay.com ‘I wish I was in schoolfriend Guido Heller ran the Worm’s Head Hotel, but at the time it Rhossili’… did not have a licence. …wrote poet and writer Dylan Thomas (when he was pining to be back home). More about Dylan And you can certainly see why; Rhossili Bay is, as Dylan also aptly put, a ‘very Many people are familiar with Dylan’s long golden beach’ on the Gower poetry and prose, some of which is Peninsula, which was the first in the influenced by Gower’s inspirational UK to be designated as an Area of countryside and coastal scenery; Outstanding Natural Beauty. but this summer, there is a unique opportunity to see some of Dylan’s A ‘VERY LONG GOLDEN personal letters and manuscripts, BEACH’ ON THE GOWER written in his own hand at an PENINSULA exceptional exhibition at Swansea’s Dylan Thomas Centre. Dylan Thomas spent his boyhood in Swansea and enjoyed camping on INFLUENCED BY Gower as depicted in his short story GOWER’S INSPIRATIONAL ‘Extraordinary Little Cough’. The COUNTRYSIDE AND COASTAL promontory of Worm’s Head is linked SCENERY to the mainland by a tidal causeway and Dylan was apt to mistime his return This exhibition is part of Dylan Thomas and get cut off by the tide – resulting 2014, a year-long celebration of his in an impromptu overnight stay on life and work in his hometown and the Worm! He writes about this in the surrounding area. story ‘Who Do You Wish Was With Us?’. -

961 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

961 bus time schedule & line map 961 Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen View In Website Mode The 961 bus line Llansamlet - Swansea College via Winch Wen has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Tycoch: 7:38 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 961 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 961 bus arriving. Direction: Tycoch 961 bus Time Schedule 59 stops Tycoch Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:38 AM Church Road, Llansamlet 141 Samlet Road, Swansea Tuesday 7:38 AM Lon-Las School, Gwernllwynchwyth Wednesday 7:38 AM Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth Thursday 7:38 AM Friday 7:38 AM Walters Road, Felin Fran Walters Road, Llansamlet Community Saturday Not Operational Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las Heol Las, Heol-Las 961 bus Info Smiths Road, Birchgrove Direction: Tycoch Stops: 59 Heol Dulais, Heol-Las Trip Duration: 53 min Line Summary: Church Road, Llansamlet, Lon-Las Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove School, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road Roundabout, Gwernllwynchwyth, Walters Road, Felin Heol Dulais, Birchgrove Community Fran, Ynysallan Road, Heol-Las, Heol Las, Heol-Las, School, Birchgrove Smiths Road, Birchgrove, Heol Dulais, Heol-Las, Heol Dulais Corner, Birchgrove, School, Birchgrove, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Road, Bridgend Inn, Birchgrove Birchgrove, Birchgrove Stores, Birchgrove, Birchgrove Hill, Peniel Green, Peniel Green East, Birchgrove Road, Birchgrove Peniel Green, Library, Peniel Green, Llansamlet Railway Station, Peniel Green, Llansamlet -

The Penthouse – Langland

Local Attractions Find us The historic village of Mumbles has many good restarants, Leave the M4 at J42 following the A483 to Swansea. Cross- cafés and cosy pubs. ing the river approaching the city centre this becomes the The Penthouse The Gower Peninsula, Britain’s first Area of Outstaning A4067. Follow this for 4 miles around beautiful Swansea Bay Langland Bay, Gower Natural Beauty is a haven for lovers of nature and the to the village of Mumbles. outdoors. We are lucky to have some of the country’s Turn right at the mini-roundabout on the edge of the village finest beaches, coastal walks, wildlife habitats and a onto Newton Road for 0.3 miles then left at traffic lights onto fascinating history. Langland road for 0.7 miles. Ignore the first left turn sign- For sports lovers there are tennis courts, golf, horse riding, posted Langland Bay. The road bends sharply to the right surfing and other water sports. Nearby Swansea has a well just before a prominent church, take the immediate left on equipped leisure centre, theatre, cinema, museums and the bend onto Brynfield Road. galleries. For the more adventurous, Gower has abundant After 60m take the first left, Langland Court Road, and the climbing and nearby Afan Valley boasts world class first left again. Follow the road for 150m then bear right onto mountain bike trails. a private lane to the Woodridge Court car park. The Penthouse, Woodridge Court, Langland, Swansea SA3 4TH Rhosilli Swansea Bracelet Bay Three Cliffs Relax... Unwind... Luxury Bookings / Contact www.gowerpenthouse.com Stella on 01792 824350 [email protected] Visit our website to join our mailing list or like us on Facebook for excu- sive offers and late availability deals. -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Ilston Community Council Held at Penmaen and Nicholaston Parish Hall on Wednesday, 28Th February 2018

Community Council Minutes of Meeting held on 28th February 2018 At a meeting of the Ilston Community Council held at Penmaen and Nicholaston Parish Hall on Wednesday, 28th February 2018: Present: Councillors Mr J Howells, Mrs F Owen-John, Mr D Ponting and Mr Roy Church. Mr John Jacobs as advisor to the Clerk. In the Chair: Councillor Mr J Howells 1. Apologies for Absence Apologies for absence were received from Councillors A. Elliott, C Grove, J Kingham, V Jones and J Griffiths. 2. Declarations of Personal Interest An interest in planning application 2017/2632/FUL for 3 ponds at Webbsfield Ilston was declared by Councillor R Church. 3. Minutes. The minutes of the meeting held on 31st January 2018 could not be taken as read as none of the Councillors present were present at the last meeting. 4. Matters Arising. On 4. Welsh Government & AONB. Watching brief be kept. On 5. Welsh Water on Cefn Bryn - No progress to date. Clerk to meet with Cllr J Howells. Cllr D Ponting reported that the work has finished but that the area is still a mess, bits of concrete lying around and wooden shuttering still in place. On 5a. Speeding in Parkmill – Nicola Mathews, PA to Ms Antoniazzi to keep council informed. On 9a. Bus Shelter at Perriswood.- the shelter has been erected and examined by Cllr F Owen-John. It has been found to be inadequate and dangerous. It is open to the prevailing winds. Three vehicles have gone into the ditch where the road is eroded adjacent to the bus shelter. -

Geographical Indications: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb

SPECIFICATION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1151/2012 on protected geographical indications and protected designations of origin “Gower Salt Marsh Lamb” EC No: PDO (X) PGI ( ) This summary sets out the main elements of the product specification for information purposes. 1 Responsible department in the Member State Defra SW Area 2nd Floor Seacole Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Tel: 02080261121 Email: [email protected] 2 Group Name: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb Group Address: Weobley Castle, Llanrhidian Gower SA3 1HB Tel.: 01792 390012 e-mail:[email protected] Composition: Producers/processors (6) Other (1) 3 Type of product Class 1.1 Fresh Meat (and offal) 4 Specification 4.1 Name: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ 4.2 Description: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is prime lamb that is born reared and slaughtered on the Gower peninsular in South Wales. It is the unique vegetation and environment of the salt marshes on the north Gower coastline, where the lambs graze, which gives the meat its distinctive characteristics. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is a natural seasonal product available from June until the end of December. There is no restriction on which breeds (or x breeds) of sheep can be used to produce ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’. However, the breeds which are the most suitable, are hardy, lighter more agile breeds which thrive well on the salt marsh vegetation. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is aged between 4 to 10 months at time of slaughter. All lambs must spend a minimum of 2 months in total, (and at least 50% of their life) grazing the salt marsh although some lambs will graze the salt marsh for up to 8 months. -

Report on the Examination Into the Swansea Local Development Plan 2010 – 2025

Adroddiad i Gyngor Report to Swansea Abertawe Council gan: by: Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM Rebecca Phillips BA (Hons) MSc DipM MRTPI MCIM MRTPI MCIM Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Paul Selby BEng (Hons) MSc MRTPI Arolygyddion a benodir gan Weinidogion Inspectors appointed by the Welsh Cymru Ministers Dyddiad: 31/01/19 Date: 31/01/19 PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 (AS AMENDED) SECTION 64 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION INTO THE SWANSEA LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2010 – 2025 Plan submitted for examination on 28 July 2017 Hearings held 6 February – 28 March 2018 and 10 – 11 September 2018 Cyf ffeil/File ref: 515477 Swansea Local Development Plan 2010-2025 – Inspectors’ Report Abbreviations used in this report AA Appropriate Assessment AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty AQMA Air Quality Management Area CBEEMS Carmarthen Bay and Estuaries European Marine Site DAMs Development Advice Maps DCWW Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water FCA Flood Consequences Assessment HRA Habitats Regulations Assessment IDP Infrastructure Delivery Plan IMAC Inspectors’ Matters Arising Change LDP Local Development Plan LHMA Local Housing Market Assessment LPA Local Planning Authority LSA Local Search Area MAC Matters Arising Change MoU Memorandum of Understanding NRW Natural Resources Wales PPW Planning Policy Wales RSL Registered Social Landlord SA Sustainability Appraisal SCARC Swansea Central Area Retail Centre SCARF Swansea Central Area Regeneration Framework SDA Strategic Development Area SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment SHPZ Strategic Housing Policy -

Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales This Events Programme Is Brought To

West Glamorgan Local Group Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales This events programme is brought to you by the West Glamorgan The Wildlife Trust of South & West Wales Local Group consisting is part of the largest UK voluntary purely of volunteers. organisation dedicated to conserving the full range of the UK's habitats and species. West Glamorgan Group Committee The Trust covers a huge area from Chairman Mark Winder Cardiff & Caerphilly in the east Secretary Elizabeth May (retiring) to Ceredigion & Pembrokeshire in the west. Treasurer John Gale (retiring) Events Jo Mullett It cares for over 90 nature reserves Members Roy Jones including 4 islands. WEST GLAMORGAN Mervyn Howells LOCAL GROUP John Ryland Volunteering Opportunities PROGRAMME 2010 Neil Jones Stewart Rowden • Conservation Volunteers • Reserve & Assistant Wardens • Education Volunteers • Administration Volunteers Note: programme subject to change. We are always looking for new • Membership recruitment committee members so if you are Please confirm details interested please get in touch. Tel: 01656 724100 Book on all outdoor events. Website www.welshwildlife.org Non-members welcome. Conservation Work If you are interested in conservation work please contact Senior Wildlife Trust Officer Senior Officer: Paul Thornton Tel: 01656 724100 E mail: [email protected] INDOOR TALKS 14th Sept, AGM Living Landscapes & Seas 21st- 22nd May, 24 Hour Biodiversity Blitz A vision of conservation for the Wildlife Trust Celebrate International Biodiversity Day by Our indoor talks start 7.30pm prompt every of South & West Wales focusing on our local discovering & recording all the flora & fauna 2nd Tuesday of the month (except July & patch. observed in 24 hours! Sarah Kessell, Wildlife Trust of South & West City & County of Swansea August) at the Environment Centre, Pier Wales th Street, Swansea. -

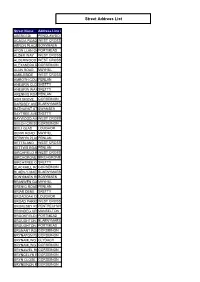

Street Address List

Street Address List Street Name Address Line 2 ABERCEDI PENCLAWDD ACACIA ROAD WEST CROSS AERON PLACEBONYMAEN AFON LLAN GARDENSPORTMEAD ALDER WAY WEST CROSS ALDERWOOD ROADWEST CROSS ALEXANDRA ROADGORSEINON ALUN ROAD MAYHILL AMBLESIDE WEST CROSS AMROTH COURTPENLAN ANEURIN CLOSESKETTY ANEURIN WAYSKETTY ARENNIG ROADPENLAN ASH GROVE GORSEINON BARDSEY AVENUEBLAENYMAES BATHURST STREETSWANSEA BAYTREE AVENUESKETTY BAYWOOD AVENUEWEST CROSS BEECH CRESCENTGORSEINON BEILI GLAS LOUGHOR BERW ROAD MAYHILL BERWYN PLACEPENLAN BETTSLAND WEST CROSS BETTWS ROADPENLAN BIRCHFIELD ROADWEST CROSS BIRCHGROVE ROADBIRCHGROVE BIRCHTREE CLOSESKETTY BLACKHILL ROADGORSEINON BLAEN-Y-MAESBLAENYMAES DRIVE BONYMAEN ROADBONYMAEN BRANWEN GARDENSMAYHILL BRENIG ROAD PENLAN BRIAR DENE SKETTY BROADOAK COURTLOUGHOR BROAD PARKSWEST CROSS BROKESBY ROADPENTRECHWYTH BRONDEG CRESCENTMANSELTON BROOKFIELD PLACEPORTMEAD BROUGHTON AVENUEBLAENYMAES BROUGHTON AVENUEPORTMEAD BRUNANT ROADGORSEINON BRYNAFON ROADGORSEINON BRYNAMLWG CLYDACH BRYNAMLWG ROADGORSEINON BRYNAWEL ROADGORSEINON BRYNCELYN ROADGORSEINON BRYN CLOSE GORSEINON BRYNEINON ROADGORSEINON BRYNEITHIN GOWERTON BRYNEITHIN ROADGORSEINON BRYNFFYNNONGORSEINON ROAD BRYNGOLAU GORSEINON BRYNGWASTADGORSEINON ROAD BRYNHYFRYD ROADGORSEINON BRYNIAGO ROADPONTARDULAIS BRYNLLWCHWRLOUGHOR ROAD BRYNMELIN STREETSWANSEA BRYN RHOSOGLOUGHOR BRYNTEG CLYDACH BRYNTEG ROADGORSEINON BRYNTIRION ROADPONTLLIW BRYN VERNEL LOUGHOR BRYNYMOR THREE CROSSES BUCKINGHAM ROADBONYMAEN BURRY GREENLLANGENNITH BWLCHYGWINFELINDRE BYNG STREET LANDORE CABAN ISAAC ROADPENCLAWDD -

14 Newton Road Mumbles Swansea Sa3 4Au

TO LET – GROUND FLOOR RETAIL UNIT 14 NEWTON ROAD MUMBLES SWANSEA SA3 4AU © Crown Copyright 2020. Licence no 100019885. Not to scale geraldeve.com Location Viewing The property is situated in the main retail pitch of Newton Strictly by appointment through sole agents, Gerald Eve LLP. Road in Mumbles. Mumbles is located four miles south west of Swansea city centre and is an affluent district which sees Legal costs many tourists throughout the year due to the nearby beaches and its tourist hotspots such as Mumbles Pier and Oystermouth Each party to bear their own costs in the transaction. Castle. Mumbles is the gateway to the Gower, the first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty to be designated in the UK. VAT The property sits 40m from the junction of Newton Road and The property is exempt from VAT and therefore VAT will not be Mumbles Road, the main arterial route from Swansea city centre payable on rent and service charge payments. to Mumbles. There is a good mix of independent and national retailers along Newton Road including Marks & Spencers, Lloyds, Co-operative Food, WH Smith and Tesco Express. EPC Description The property comprises a ground floor retail unit with glazed frontage and recessed access doors under a canopy that extends along the north side of Newton Road. Internally the unit comprises a generous sales area that is regular in shape, leading to a storage area, an office and WC’s. The property benefits from external storage and additional access at the rear. Floor area Ground floor Sales 552 sq ft Ground Floor Ancillary 76 sq ft External rear store 76 sq ft Contact Tom Cater Tenure [email protected] Available to let on a new lease on terms to be negotiated.