Cjnh 2013 2 Cs5 Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Phylogeny, Divergence Times and Biogeography of Spiders of the Subfamily Euophryinae (Araneae: Salticidae) ⇑ Jun-Xia Zhang A, , Wayne P

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2013) 81–92 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molec ular Phylo genetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Molecular phylogeny, divergence times and biogeography of spiders of the subfamily Euophryinae (Araneae: Salticidae) ⇑ Jun-Xia Zhang a, , Wayne P. Maddison a,b a Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 b Department of Botany and Beaty Biodiversity Museum, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 article info abstract Article history: We investigate phylogenetic relationships of the jumping spider subfamily Euophryinae, diverse in spe- Received 10 August 2012 cies and genera in both the Old World and New World. DNA sequence data of four gene regions (nuclear: Revised 17 February 2013 28S, Actin 5C; mitochondrial: 16S-ND1, COI) were collected from 263 jumping spider species. The molec- Accepted 13 March 2013 ular phylogeny obtained by Bayesian, likelihood and parsimony methods strongly supports the mono- Available online 28 March 2013 phyly of a Euophryinae re-delimited to include 85 genera. Diolenius and its relatives are shown to be euophryines. Euophryines from different continental regions generally form separate clades on the phy- Keywords: logeny, with few cases of mixture. Known fossils of jumping spiders were used to calibrate a divergence Phylogeny time analysis, which suggests most divergences of euophryines were after the Eocene. Given the diver- Temporal divergence Biogeography gence times, several intercontinental dispersal event sare required to explain the distribution of euophry- Intercontinental dispersal ines. Early transitions of continental distribution between the Old and New World may have been Euophryinae facilitated by the Antarctic land bridge, which euophryines may have been uniquely able to exploit Diolenius because of their apparent cold tolerance. -

Rural Development for Cambodia Key Issues and Constraints

Rural Development for Cambodia Key Issues and Constraints Cambodia’s economic performance over the past decade has been impressive, and poverty reduction has made significant progress. In the 2000s, the contribution of agriculture and agro-industry to overall economic growth has come largely through the accumulation of factors of production—land and labor—as part of an extensive growth of activity, with productivity modestly improving from very low levels. Despite these generally positive signs, there is justifiable concern about Cambodia’s ability to seize the opportunities presented. The concern is that the existing set of structural and institutional constraints, unless addressed by appropriate interventions and policies, will slow down economic growth and poverty reduction. These constraints include (i) an insecurity in land tenure, which inhibits investment in productive activities; (ii) low productivity in land and human capital; (iii) a business-enabling environment that is not conducive to formalized investment; (iv) underdeveloped rural roads and irrigation infrastructure; (v) a finance sector that is unable to mobilize significant funds for agricultural and rural development; and (vi) the critical need to strengthen public expenditure management to optimize scarce resources for effective delivery of rural services. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its Rural Development developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million for Cambodia struggling on less than $1.25 a day. -

Western Ghats), Idukki District, Kerala, India

International Journal of Entomology Research International Journal of Entomology Research ISSN: 2455-4758 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.entomologyjournals.com Volume 3; Issue 2; March 2018; Page No. 114-120 The moths (Lepidoptera: Heterocera) of vagamon hills (Western Ghats), Idukki district, Kerala, India Pratheesh Mathew, Sekar Anand, Kuppusamy Sivasankaran, Savarimuthu Ignacimuthu* Entomology Research Institute, Loyola College, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract The present study was conducted at Vagamon hill station to evaluate the biodiversity of moths. During the present study, a total of 675 moth specimens were collected from the study area which represented 112 species from 16 families and eight super families. Though much of the species has been reported earlier from other parts of India, 15 species were first records for the state of Kerala. The highest species richness was shown by the family Erebidae and the least by the families Lasiocampidae, Uraniidae, Notodontidae, Pyralidae, Yponomeutidae, Zygaenidae and Hepialidae with one species each. The results of this preliminary study are promising; it sheds light on the unknown biodiversity of Vagamon hills which needs to be strengthened through comprehensive future surveys. Keywords: fauna, lepidoptera, biodiversity, vagamon, Western Ghats, Kerala 1. Introduction Ghats stretches from 8° N to 22° N. Due to increasing Arthropods are considered as the most successful animal anthropogenic activities the montane grasslands and adjacent group which consists of more than two-third of all animal forests face several threats (Pramod et al. 1997) [20]. With a species on earth. Class Insecta comprise about 90% of tropical wide array of bioclimatic and topographic conditions, the forest biomass (Fatimah & Catherine 2002) [10]. -

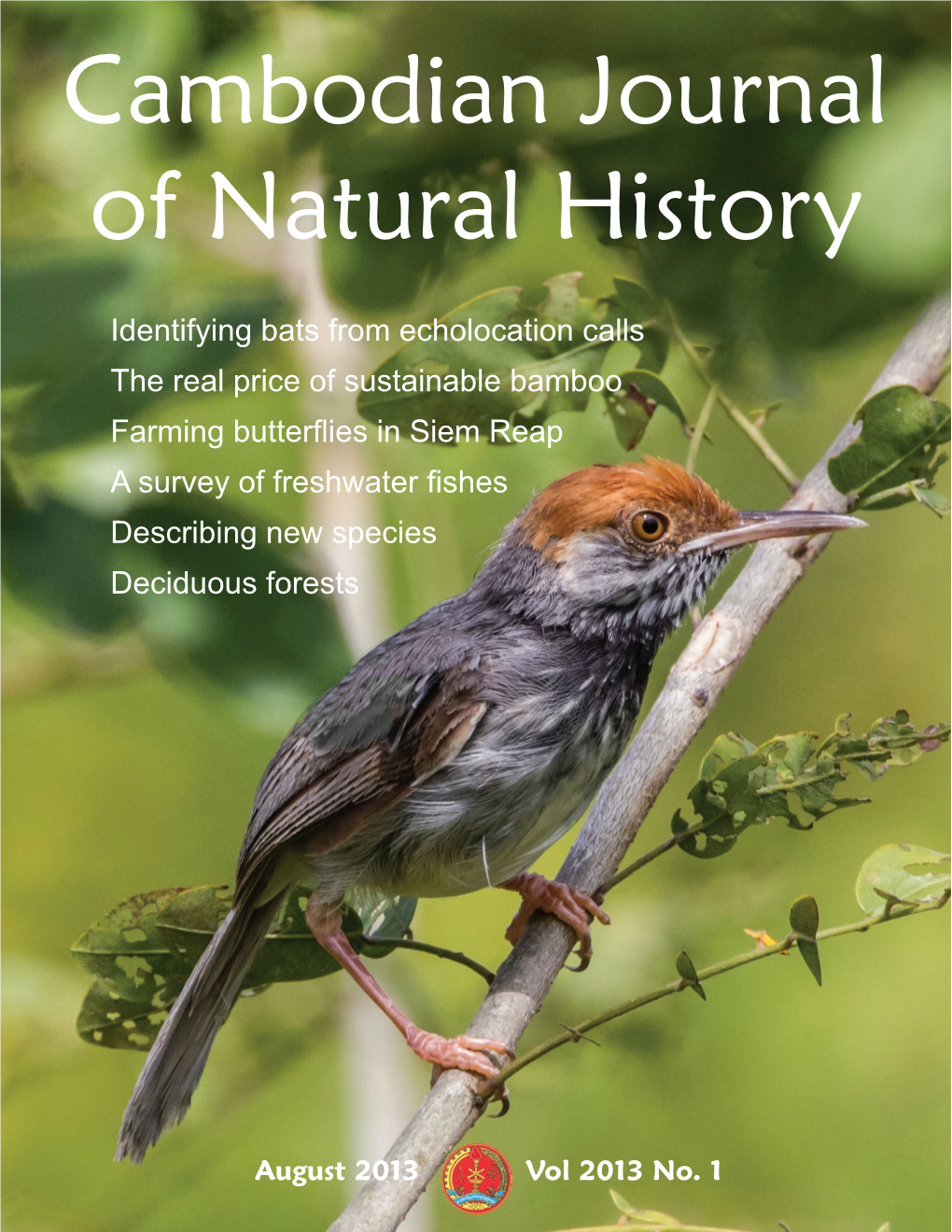

Passeriformes: Cisticolidae: Orthotomus) from the Mekong Floodplain of Cambodia

FORKTAIL 29 (2013): 1–14 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F1778491-B6EE-4225-95B2-2843B32CBA08 A new species of lowland tailorbird (Passeriformes: Cisticolidae: Orthotomus) from the Mekong floodplain of Cambodia S. P. MAHOOD, A. J. I. JOHN, J. C. EAMES, C. H. OLIVEROS, R. G. MOYLE, HONG CHAMNAN, C. M. POOLE, H. NIELSEN & F. H. SHELDON Based on distinctive morphological and vocal characters we describe a new species of lowland tailorbird Orthotomus from dense humid lowland scrub in the floodplain of the Mekong, Tonle Sap and Bassac rivers of Cambodia. Genetic data place it in the O. atrogularis–O. ruficeps–O. sepium clade. All data suggest that the new species is most closely related to O. atrogularis, from which genetic differences are apparently of a level usually associated with subspecies. However the two taxa behave as biological species, existing locally in sympatry and even exceptionally in syntopy, without apparent hybridisation. The species is known so far from a small area within which its habitat is declining in area and quality. However, although birds are found in a number of small habitat fragments (including within the city limits of Phnom Penh), most individuals probably occupy one large contiguous area of habitat in the Tonle Sap floodplain. We therefore recommend it is classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. The new species is abundant in suitable habitat within its small range. Further work is required to understand more clearly the distribution and ecology of this species and in particular its evolutionary relationship with O. atrogularis. INTRODUCTION and its major tributaries (Duckworth et al. -

Malaria in the Greater Mekong Subregion

his report provides an overview of the epidemiological patterns of malaria in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Tfrom 1998 to 2007, and highlights critical challenges facing National Malaria Control Programmes and partners as they move towards malaria elimination as a programmatic goal. Epidemiological data provided by malaria programmes show a drastic decline in malaria deaths and confirmed malaria cases over the last 10 years in the GMS. More than half of confirmed malaria cases and deaths in the GMS occur in Myanmar. However, reporting methods and data management are not comparable between countries despite the effort made by WHO to harmonize data collection, analysis and reporting among Member States. Malaria is concentrated in forested/forest-fringe areas of the Region, mainly along international borders. This providing a strong rationale to develop harmonized cross-border elimination programmes in conjunction with national efforts. Across the Mekong Region, the declining efficacy of recommended first-line antimalarials, e.g. artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) against falciparum malaria on the Cambodia-Thailand border; the prevalence of counterfeit and substandard antimalarial drugs; the Malaria lack of health services in general and malaria services in particular in remote settings; and the lack of information and services in the Greater Mekong Subregion: targeting migrants and mobile population present important barriers to reach or maintain malaria elimination programmatic Regional and Country Profiles goals. Strengthening -

Mekong River in the Economy

le:///.le/id=6571367.3900159 NOVEMBER REPORT 2 0 1 6 ©THOMAS CRISTOFOLETTI / WWF-UK In the Economy Mekong River © NICOLAS AXELROD /WWF-GREATER MEKONG Report prepared by Pegasys Consulting Hannah Baleta, Guy Pegram, Marc Goichot, Stuart Orr, Nura Suleiman, and the WWF-Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam teams. Copyright ©WWF-Greater Mekong, 2016 2 Foreword Water is liquid capital that flows through the economy as it does FOREWORD through our rivers and lakes. Regionally, the Mekong River underpins our agricultural g systems, our energy production, our manufacturing, our food security, our ecosystems and our wellbeing as humans. The Mekong River Basin is a vast landscape, deeply rooted, for thousands of years, in an often hidden water-based economy. From transportation and fish protein, to some of the most fertile crop growing regions on the planet, the Mekong’s economy has always been tied to the fortunes of the river. Indeed, one only need look at the vast irrigation systems of ancient cities like the magnificent Angkor Wat, to witness the fundamental role of water in shaping the ability of this entire region to prosper. In recent decades, the significant economic growth of the Lower Mekong Basin countries Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Viet Nam — has placed new strains on this river system. These pressures have the ability to impact the future wellbeing including catalysing or constraining the potential economic growth — if they are not managed in a systemic manner. Indeed, governments, companies and communities in the Mekong are not alone in this regard; the World Economic Forum has consistently ranked water crises in the top 3 global risks facing the economy over the coming 15 years. -

Three Interesting Spiders of the Families Filistatidae, Clubionidae and Salticidae (Araneae) from Palau

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. A, 37(4), pp. 185–194, December 22, 2011 Three Interesting Spiders of the Families Filistatidae, Clubionidae and Salticidae (Araneae) from Palau Hirotsugu Ono Department of Zoology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1, Amakubo, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki, 305–0005 Japan E-mail: [email protected] (Received 29 August 2011; accepted 28 September 2011) Abstract Three interesting spiders from the Republic of Palau are reported. Filistata fuscata Nakatsudi, 1943 (Filistatidae), is taxonomically revised and redescribed with topotypical speci- mens newly obtained. Nakatsudi is regarded as the only author of the name, contrary to the hither- to treatments in the catalogues as Kishida, 1943 or Kishida in Nakatsudi, 1943. Filistata fuscata Kishida, 1947, validated on the basis of Kishida (1947) as its original description is regarded as a junior homonym and synonym of Filistata fuscata Nakatsudi, 1943. After a careful assessment of characteristics, the species is transferred from the original genus into Tricalamus Wang, 1987, and a new combination Tricalamus fuscatus is proposed. Two new species of the genera Clubiona La- treille, 1804 (Clubionidae) and Athamas O. Pickard-Cambridge, 1877 (Salticidae), are described from Koror Island of Palau under the names, Clubiona jaegeri sp. nov. and Athamas proszynskii sp. nov., respectively. Key words : Taxonomy, Araneae, Filistatidae, Clubionidae, Salticidae, Palau. In the course of research project on the biodi- The abbreviations used are as follows: ALE, versity inventory in western Pacific regions made anterior lateral eye; AME, anterior median eye; by the National Museum of Nature and Science, ap, in the apical part; PLE, posterior lateral eye; Tokyo, the author visited the Republic of Palau PME, posterior median eye. -

Bombyx Mori Silk Fibers Released from Cocoons by Alkali Treatment

Journal of Life Sciences and Technologies Vol. 3, No. 1, June 2015 Mechanical Properties and Biocompatibility of Attacus atlas and Bombyx mori Silk Fibers Released from Cocoons by Alkali Treatment Tjokorda Gde Tirta Nindhia and I. Wayan Surata Department of Mechanical Engineering, Udayana University, Jimbaran, Bali, Indonesia, 80361 Email: [email protected] Zdeněk Knejzlík and Tomáš Ruml Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, Institute of Chemical Technology, Prague, Technická 5, 166 28, Prague, Czech Republic Tjokorda Sari Nindhia Faculty of veterinary Madicine, Udayana University, Jl. P.B. Sudirman, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia, 80114 Abstract—Natural silks, produced by spiders and insects, historically used in textile industry [6]. Fibers present in represent perspective source of biomaterials for the cocoons are mainly composed from fibroin complex regenerative medicine and biotechnology because of their [7] produced from paired labial glands [8]. About 10 – 12 excellent biocompatibility and physico-chemical properties. μm fibroin fibers in B. mori cocoon are tethered by It was previously shown that silks produced by several amorphous protein; sericin, which can be released from members of Saturniidae family have excellent properties in comparison to silk from B. mori, the most studied silkworm. cocoon by washing in mild alkali conditions or hot water, Efficient degumming of silk fibers is a critical step for a process, designated as degumming [9]. Fine fibers, subsequent processing of fibers and/or fibroin. In this study, obtained by degumming, can be used as source of fibroin we describe cheap, environmentally friendly and efficient which may be next solubilized in denaturing agents such NaOH-based degumming of A. atlas fibers originated from as highly concentrated solution of lithium salts, calcium natural cocoon. -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

The Evolutionary Tree of Birds

HANDBOOK OF BIRD BIOLOGY THE CORNELL LAB OF ORNITHOLOGY HANDBOOK OF BIRD BIOLOGY THIRD EDITION EDITED BY Irby J. Lovette John W. Fitzpatrick Editorial Team Rebecca M. Brunner, Developmental Editor Alexandra Class Freeman, Art Program Editor Myrah A. Bridwell, Permissions Editor Mya E. Thompson, Online Content Director iv This third edition first published 2016 © 2016, 2004, 1972 by Cornell University Edition history: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology (1e, 1972); Princeton University Press (2e, 2004) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774, USA For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

2009 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Hilton Portland & Executive Tower Portland, Oregon 23 July 2009 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University College of Arts & Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - ECS 450 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 23 June 2009 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 22 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Pavillion East in the Hilton Portland and Executive Tower. President Lundberg plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book which covers society business from 2008 and 2009. The book includes the ballot information for the 2009 elections (Board of Govenors and Annual Business Meeting). Governors can ask to have items exempted from blanket approval. These exempted items will will be acted upon individually. We will also act individually on items exempted by the Executive Committee. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Portland. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Portland (via Davis, CA)on 18 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive in Portland late on the afternoon of 20 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 26 July 2009 from 1800-2000 h in Galleria North. -

Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Molecular systematics of the subfamily Limenitidinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Bidur Dhungel1 and Niklas Wahlberg2 1 Southwestern Centre for Research and PhD Studies, Kathmandu, Nepal 2 Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden ABSTRACT We studied the systematics of the subfamily Limenitidinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphal- idae) using molecular methods to reconstruct a robust phylogenetic hypothesis. The molecular data matrix comprised 205 Limenitidinae species, four outgroups, and 11,327 aligned nucleotide sites using up to 18 genes per species of which seven genes (CycY, Exp1, Nex9, PolII, ProSup, PSb and UDPG6DH) have not previously been used in phylogenetic studies. We recovered the monophyly of the subfamily Limenitidinae and seven higher clades corresponding to four traditional tribes Parthenini, Adoliadini, Neptini, Limenitidini as well as three additional independent lineages. One contains the genera Harma C Cymothoe and likely a third, Bhagadatta, and the other two indepen- dent lineages lead to Pseudoneptis and to Pseudacraea. These independent lineages are circumscribed as new tribes. Parthenini was recovered as sister to rest of Limenitidinae, but the relationships of the remaining six lineages were ambiguous. A number of genera were found to be non-monophyletic, with Pantoporia, Euthalia, Athyma, and Parasarpa being polyphyletic, whereas Limenitis, Neptis, Bebearia, Euryphura, and Adelpha were paraphyletic. Subjects Biodiversity, Entomology, Taxonomy Keywords Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Systematics, New tribe, Classification, Limenitidinae Submitted 22 November 2017 Accepted 11 January 2018 Published 2 February 2018 INTRODUCTION Corresponding author Niklas Wahlberg, The butterfly family Nymphalidae has been the subject of intensive research in many fields [email protected] of biology over the decades.