Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carolynbrowncv10.2019

Carolyn E. Brown www.carolynebrown.com [email protected] [email protected] (551) 208-7949 EDUCATION MA, Liberal Studies, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ Focus: Ethnic Studies/Anthropology Thesis Topic: Anti-Immigrant/Militia Movements/Latino Identity BA, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY Dual Major: Political Science, Art/Art History Senior Thesis Project in Art/Art History: grade earned – A+ Thesis: Documentary Film produced – subject: Latino Identity Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, 1994 Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 1994 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT HISTORY August 2017 to present Senior Lecturer, Mayborn School of Journalism University of North Texas, Denton, TX August 2010 to August 2017 Assistant Professor, Journalism Division American University, Washington, DC August 2008 to July 2010 Assistant Professor, Journalism Division, term line American University, Washington, DC August 2006 to May 2008 Part-time faculty, Journalism, Electronic Media/Film Departments Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT HISTORY EARTH MEDIA STUDIOS, Phoenix, AZ Senior Producer, 2006 Launched Arizona Entertainment Weekly Created, produced pilots for new entertainment shows Hired staff for new shows 1 FOX NEWS CHANNEL, New York, NY Line Producer, 2003—2005 Produced Sunday Housecall with Dr. Isadore Rosenfeld Produced 1 and 2-hour news shows for Fox News Live Produced Special Election Coverage MSNBC NEWS, Secaucus, New Jersey Line Producer, 2002—2003 Produced 1 and 2-hour news shows Produced Buchanan -

CURRICULUM VITAE Anthony D'agostino Department of History

CURRICULUM VITAE Anthony D’Agostino Department of History San Francisco State University San Francisco, CA 94132 home address: 4815 Harbord Drive, Oakland, CA 94618 phone: (415) 338 7535 email: [email protected] EDUCATION B.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1959 M.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1962 Graduate Study, University of Warsaw, 196768 Ph.D., University of California, Los Angeles, 1971 HONORS AND AWARDS: Teaching Assistantship, UCLA, 196566 Teaching Assistantship, UCLA, 196667 Research Fellowship, University of Warsaw (StanfordWarsaw Exchange), 196768 Research Assistantship, Russian and East European Studies Center, UCLA, 196869 Research Fellowship, Frederick Burk Foundation, San Francisco State University, 1971 Research Fellowship for Younger Humanists, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1973 Research Fellowship in Soviet and East European Studies (Title VIII), U.S. State Department and Hoover Institution, 198687 Meritorious Performance and Professional Promise Award, San Francisco State University, 198687 Meritorious Performance and Professional Promise Award, San Francisco State University, 198889 Choice cites Soviet Succession Struggles on its list of “outstanding academic books” for 198889. Encyclopedia Britannica 1989 Yearbook cites Soviet Succession Struggles in its select international bibliography. Performance Salary Increase, San Francisco State University, 1998. MEMBERSHIPS: World Association of International Studies (Stanford) American Historical Association The History Society International Institute of Strategic Studies (London) Royal United Services Institute for Defense Studies (London) InterUniversity Seminar on Armed Forces and Society American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies Great War Society Western Social Science Association Northern California World Affairs Council Electronic mail groups HRussia, HDiplo, HIdeas, HWorld, Johnson’s Russia List and others. -

Sly Fox Buys Big, Gets Back On

17apSRtop25.qxd 4/19/01 5:19 PM Page 59 COVERSTORY Sly Fox buys big, The Top 25 gets back on top Television Groups But biggest station-group would-be Spanish-language network, Azteca America. Rank Network (rank last year) gainers reflect the rapid Meanwhile, Entravision rival Telemundo growth of Spanish-speaking has made just one deal in the past year, cre- audiences across the U.S. ating a duopoly in Los Angeles. But the 1 Fox (2) company moved up several notches on the 2 Viacom (1) By Elizabeth A. Rathbun Top 25 list as Univision swallowed USA. ending the lifting of the FCC’s owner- In the biggest deal of the past year, News 3 Paxson (3) ship cap, the major changes on Corp./Fox Television made plans to take 4 Tribune (4) PBROADCASTING & CABLE’s compila- over Chris-Craft Industries/United Tele- tion of the nation’s Top 25 TV Groups reflect vision, No. 7 on last year’s list. That deal 5 NBC (5) the rapid growth of the Spanish-speaking finally seems to be headed for federal population in the U.S. approval. 6 ABC (6) The list also reflects Industry consolidation But the divestiture 7 Univision (13) the power of the Top 25 doesn’t alter that News Percent of commercial TV stations 8 Gannett (8) groups as whole: They controlled by the top 25 TV groups Corp. returns to the control 44.5% of com- top after buying Chris- 9 Hearst-Argyle (9) mercial TV stations in Craft. This year, News the U.S., up about 7% Corp. -

P-91

p-91 (Qcp-iow*e cOorCK P^6^touOG= ^^CgLLAMStxJX ( £ £ 0 '2-ooJ (HTtf^ui€.t^<; /v^»«D Tgi^Jh,£*®P pP=OvSAArnx £>*T T v ( ^ H m A(10 iH JT 'T uT£ JCIXjd^j ~ v S £ve^£-«vVKML'1, jK M or^ ■yi ■HHHHMHBH HI September 10, 2003 Dear Oral History Participant, Thank you for participation in the History project. I'm happy to report that the West Coast Oral History videos have just been placed in the African American Museum and Library in Oakland. I have enclosed your personal copy for your video library. Also, as you may know, Earl recently was appointed the position of Endowed Chair at the Hampton School of Journalism. He will be continuing the Oral History project in conjunction with Hampton. It is his hope that Hampton will join MIJE in hosting a celebration of the West Coast Oral History Project. He will contact you with an update on the project and our future collaboration. I will be in touch in with any future information. Again, thanks for your participation. Best regards, Amanda Elliott I Program Coordinator 409 Thirteenth Street, 9th Floor, Oakland, CA 94612 t: (510) 891-9202, f: (510) 891-9565, e: [email protected] BAYlTV PresS Release Date: March 23,1999 Contact: Jodie Chase (415)561-8658 Number: 99-3-51 ’ t REOfflVED MAR 2 S 1999 Ken Kaplan (415)561-8724 i “*■«* »', V' _ “PORT CHICAGO MUTINY: A NATIONAL TRAGEDY” - BAYTV TO PRESENT REBROAPCAST OF KRON-TV’S AWARD-WINNING DOCUMENTARY “I told my officer several times that one day this stuff is going to explode, and his answer was, ‘If it does, you and I won’t know anything about it.’ So we just continued to work.” — Joe Small, a seaman who was later charged with mutiny in the Port Chicago Trial (San Francisco) - With renewed interest in The World War II Port Chicago Mutiny case, BayTV will rebroadcast KRON’s Emmy Award-winning documentary, “Port Chicago Mutiny: A National Tragedy.” Hosted by actor Danny Glover, the documentary looks at the controversial trial which found 50 African American soldiers guilty of mutiny after they refused to return to work following a huge munitions explosion. -

Stanford University, News and Publication Service, Audiovisual Recordings Creator: Stanford University

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dn43sv Online items available Guide to the Stanford News Service Audiovisual Recordings SC1125 Daniel Hartwig & Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2012 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stanford News SC1125 1 Service Audiovisual Recordings SC1125 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University, News and Publication Service, audiovisual recordings creator: Stanford University. News and Publications Service Identifier/Call Number: SC1125 Physical Description: 63 Linear Feetand 17.4 gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1936-2011 Information about Access The materials are open for research use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Cite As [identification of item], Stanford University, News and Publication Service, Audiovisual Recordings (SC1125). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

Newstrak Videotape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8zp4d11 No online items Guide to the NewsTrak videotape collection April Austin and Sean Heyliger Center for Sacramento History 551 Sequoia Pacific Blvd. Sacramento, California 95811-0229 Phone: (916) 808-7072 Fax: (916) 264-7582 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.centerforsacramentohistory.org/ © 2013 Center for Sacramento History. All rights reserved. Guide to the NewsTrak videotape MS0037 1 collection Guide to the NewsTrak videotape collection Collection number: MS0037 Center for Sacramento History Sacramento, CA Processed by: April Austin and Sean Heyliger Date Completed: 10/04/2019 Encoded by: Sean Heyliger © 2013 Center for Sacramento History. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: NewsTrak videotape collection Dates: 1987-2006 Collection number: MS0037 Creator: NewsTrak Collection Size: 91 linear feet (91 boxes) Repository: Center for Sacramento History Sacramento, California 95811-0229 Abstract: The NewsTrak Videotape Collection consists 91 boxes of media coverage collected by the NewsTrak media monitoring firm from various television news stations, public relations firms, and government, corporate and non-profit public relations departments in the Sacramento area between 1987-2006. Media coverage includes media releases by local public relations firm Runyon, Saltzman & Einhorn, coverage of local and state politicians including Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gray Davis, and Pete Wilson during their terms as California governor, the Rodney King verdict, Proposition -

UPPNET Winter Keyline Q6

YOUR LAST FREE ISSUE UPPNETUPPNET News See Back Page Official Publication of the Union Producers and Programmers Network Winter 1998 Promoting production and use of tv and radio shows pertinent to the cause of organized labor and working people Historic Seoul L a b o r M e d i a Conference Held International Labor Communication Solidarity Growing by Steve Zeltzer, Producer Labor Video Project LaborNet-IGC Str. Ctte., UPPNET, Str. Ctte. On Nov. 10-12 in Seoul, South Ko re a , a c t ivists in lab o r video, computer, media and labor teachers from around the world met to hold a labor telecommunications conference. It was no accident the confe rence took place in Ko rea. Th e Some of the intern ational guests at Confe re n c e : (L to R) Chris Bailey, m a s s ive Ko r ean labor upheaval and ge n e ral stri ke held in L ab o u rn e t , UK; Steve Zeltze r, U P P N E T / L a bor Video Pro j e c t , USA; Dave December 1996 and January 1997 had brought not only the Ohlenroth, Labor Beat, USA; Julius Fisher, UPPNET/working tv, Canada ignition of the Korean labor movement but an international c o m mu n i c ati on netwo rk that helped back the stri ke. The con- was sponsored not only by many labor video, computer and fe rence also came on the heels of the LaborTECH confe r- l abo r info rm at i o n / e d u c a tion orga n i z ations but also by the ence held in San Francisco in Ju l y and co-sponsored by Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU). -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

E1046 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks May 20, 1999 and long-term commitment; strong leadership CONGRATULATING LEON MED- TAIWAN'S 3RD ANNIVERSARY OF and disciplinary policies; staff development; VEDOW ON HIS 70TH BIRTHDAY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS parental involvement; interagency partnerships and community links; and a culturally sensitive HON. TERRY EVERETT and developmentally appropriate approach. HON. ROSA L. DeLAURO OF ALABAMA I am proud to join my colleague from New OF CONNECTICUT IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Jersey, Congressman ROBERT MENENDEZ as a Thursday, May 20, 1999 cosponsor of the School Anti-Violence Em- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES powerment Act because it includes many of Mr. EVERETT. Mr. Speaker, for the first Thursday, May 20, 1999 the recommendations of the GAO report. This time in Chinese history, Taiwan held a truly democratic presidential election three years bill would: Ms. DELAURO. Mr. Speaker, it gives me Provide grants for school districts to hire cri- ago. As the people of Taiwan celebrate their great pleasure to rise today to recognize Leon president's third anniversary in office on May sis prevention counselors and fund anti-school Medvedow as he celebrates his 70th birthday. violence initiatives. 50% of the grants would 20, 1999, I send them my congratulations. This evening friends, family, and the New I applaud President Lee's recent proposal go to fund crisis prevention counselors and Haven community will gather to pay tribute to that Taiwan and the mainland work together in crisis prevention programs. 50% would go to Leon for a lifetime of contributions to the City drafting a comprehensive financial plan to help school districts who would have the flexibility of New Haven. -

29 Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY AWARD

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES SAN FRANCISCO / NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CHAPTER 4317 Camden Avenue e-mail: [email protected] San Mateo, California 94403-5007 http://www.emmyonline.org/sanfrancisco (650) 341-7786 SF (415) 777-0212 Fax: (650) 372-0279 A non-profit association dedicated to the advancement of television. 29th Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED The 29th Annual Northern California Area EMMY Award Nominations were announced tonight at KQED in San Francisco, as well as Mission Rogelio’s in Sacramento, the Elbow Room in Fresno, and on the Internet. The EMMY is awarded by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. San Francisco/Northern California is one of the eighteen chapters awarding local Emmys. Northern California is composed of television and cable stations from Visalia to the Oregon border and includes Hawaii and Reno, Nevada. Entries were aired during the 1999 calender year. The ballots, which were tallied by the accounting firm of Spalding & Company, totaled 158 nominations from 649 entries received in 45 categories. KRON, San Francisco, topped the nominations with 21, followed by KGO, San Francisco, and KTVU, Oakland, with 16. KPIX, San Francisco was next with 15. Cable did well with FOX Sports Net and ZDTV each receiving 10. Sacramento was next with KCRA receiving 9 and KXTV 7. Awards chair, David Mills, was pleased to see the smaller cable stations being involved in the Community Service Category. Leading the list of individuals receiving nominations: Wayne Freedman, KGO/ABC7, Ted Griggs, FOX Sports Net, and Nancy Juliber, ZDTV, each with four. -

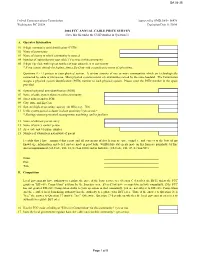

2004 FCC ANNUAL CABLE PRICE SURVEY (Save This File Under the CUID Number in Question 1)

DA 04-35 Federal Communications Commission Approved by OMB 3060 - 06476 Washington, DC 20554 Expiration Date 11/30/06 2004 FCC ANNUAL CABLE PRICE SURVEY (Save this file under the CUID number in Question 1) A. Operator Information 01 6-digit community unit identification (CUID) 02 Name of community 03 Name of county in which community is situated 04 Number of subscribers to your cable TV service in this community 05 5-digit Zip Code with highest number of your subscribers in community * If you cannot identify the highest, then a Zip Code with a significant portion of subscribers. Questions 6 - 11 pertain to your physical system. A system consists of one or more communities which are technologically connected by cable or microwave. Most physical systems consist of communities served by the same headend. The Commission assigns a physical system identification (PSID) number to each physical system. Please enter the PSID number in the space provided. 06 System's physical unit identification (PSID) 07 Name of cable system that serves this community 08 Street address and/or POB 09 City, state, and Zip Code 10 System's highest operating capacity (in MHz, e.g., 750) 11 Is this system part of a cluster in close proximity? (yes or no) * * Sharing common personnel, management, marketing, and/or facilities. 12 Name of ultimate parent entity 13 Name of survey contact person 14 Area code and telephone number 15 Number of subscribers nationwide of parent I certify that I have examined this report and all statements of fact herein are true, complete, and correct to the best of my knowledge, information, and belief, and are made in good faith. -

November 2000

ZJ FRANCISCO POLICE OFFICERS' ASSOCIATION VOLUME 32, NUMBER 11 SAN FRANCISCO, NOVEMBER 2000 www.sfpoa.org Layne Amiot PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE By Chris Cunnie By Nick Shihadeh and Matt Gardner e enter the last two months On Friday Oct. 27th, 2000 the of the year with mixed emo- police sergeant's mold was broken. W tions. On the one hand, we That was the day that SFPD member are proud to honor all of America's Layne Amiot star #1526 passed away. military veterans. On the other, we He was the most senior sergeant of pause with sadness to remember two patrol and definitely one of the most of our own —James Guelff and Layne well liked. He is also someone who Amiot. will be missed by many. Officer James Guelff was gunned Layne Amiot was a third genera- down on November 14, 1994. Part of tion native San Franciscan who at- his legacy rides on the hip of each us in tended Horace Mann Junior High, the form of a .40 caliber Beretta hand Polytechnic High School, and SF gun. It was Jim's terrible ordeal of State University. He joined the po- being out-gunned by a body armored lice department in 1967 and was tion Committee, and was a member madman that prompted the depart- promoted to sergeant out of the old of the Widows and Orphans Asso- ment to replace our old revolvers with Potrero Station in 1978. He had stints ciation. It could be said that he was the automatics we now pack. But, at the old Northern Station, the old responsible for the positive change thanks to his brother, Lee Guelff, Jim realized we had all lost a true friend, Mission Station, Southern Station in direction that the POA has taken will leave a larger legacy the James and a dedicated police officer. -

Jennifer Bermon

EXHIBITION: Jennifer Bermon “Her | Self: Women in Their Own Words” SHOW DATES: February 7 – April 4 RECEPTION: Saturday, February 7, 6-8 pm GALLERY HOURS: Tuesday – Saturday, 11 am – 6pm Jennifer Bermon presents photographs of women, and the writings of these women describing, in their own words, how they feel about the way they look in the pictures. In the United States, we grow up feeling as if our bodies are manifestations of our inner selves, and perhaps because of the power of such beliefs we offer these sometimes negative comments about ourselves. For example, when Bermon was a student at Mills College, she listened to the comments some of her friends made about themselves, “these were intelligent, strong, beautiful women … yet they still felt the need to be thin and attractive in order to be accepted.” Bermon has taken photographs of a diverse group of women who have a wide range of things to say, many of which are positive and hopeful. Bermon did not have her own expectations; she instead wishes to listen to the women as they describe themselves, in their own voice. The exhibit includes a history-making NYC firefighter, a woman who has sailed around the world twice, a NASA scientist, an actress, a judge, a farmer, a 74- year-old Rabbi, a Southern reverend, an Academy Award-winning screenplay writer and an Emmy Award-winning producer. Bermon attended Mills College, and studied photography with Catherine Wagner as part of her self-designed major of photography, art and writing. She has been working as a professional photographer since age 18, when her first portrait was published.