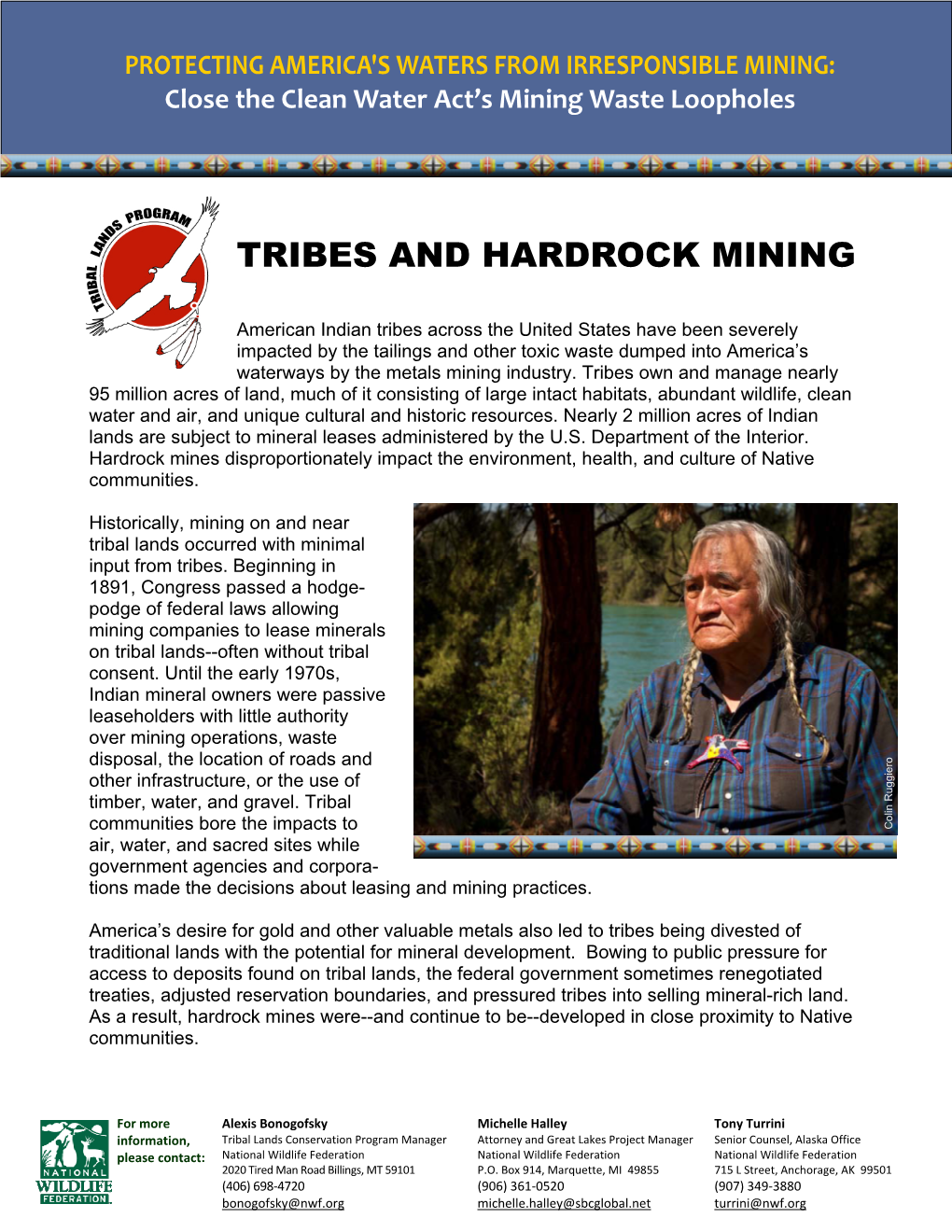

Tribes and Hardrock Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silver Valley Idaho 2010–2011 Community Resource & Relocation Guide

EDUCATION economic overvieW housinG RECREATION medical silver valley idaho 2010–2011 community resource & relocation Guide www.nygaardpromotions.com The Mouse Pad Hello, neighbor! 208.682.3669 509.723.2293 You are the center of our business • Computer Services WardwellWardwell InsuranceInsurance AgcyAgcy Inc Please stop by and say, “Hi!” • Home and Small Office Networking AnitaAnita Wardwell,Wardwell, Agent Kellogg, ID 83837 I’m looking forward to serving • Information Technology Sales 416Bus: W 208-784-1388 Cameron Ave Kellogg, ID 83837 your needs for insurance and www.anitawardwell.comBus: 208-784-1388 • Onsite Services www.anitawardwell.com financial services. Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.® CALL ME TODAY. 2 locations to serve you better 606 N Division St Pinehurst ID | 208.682.3669 17813 E Appleway Suite B Spokane Valley WA | 509.723.2293 1001013 State Farm, Bloomington, IL BUILDING MAINTENANCE AND SUPPLY INC. Serving the Silver Valley for Over 38 Years! • Lumber & Building Materials • Hardware • Paint Center • Plumbing & Electrical • Carpet & Appliances • Hunting & Fishing Supplies • Camping Supplies • Gold Panning Supplies WALLACE START RIGHT. START HERE.® 716 Bank Street Wallace, Idaho 208-556-1164 WELCOME TO SILVER VALLEY . he Silver Valley, heart of Shoshone County, is cradled between the Coeur d’Alene Mountains and the Bitterroot Range Tamong the pristine wilderness of Northern Idaho. Surrounded by lush green mountains, rugged canyons, rushing streams and crystal clear alpine lakes, this valley overflows with natural resources. The Silver Valley is one of the first frontiers of the Pacific Northwest and has a history as rich as its wealth from the silver, gold, lead and zinc mines. -

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2019

Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2019 Virginia S. Gillerman Idaho Geological Survey (Boise) www.idahogeology.org American Exploration and Mining Association Reno, NV December 4, 2019 Acknowledgements AEMA Idaho Dept. of Lands staff BLM and USFS minerals staff Industry geologists IGS and Claudio Berti (new IGS Director) Earl Bennett 2019 Trends and Highlights Phosphate Reigns in Idaho Lucky Friday strike? Gold Renaissance – North, South and in between! Cobalt/Critical Minerals Price Matters Social License and Public Perception Exciting Development Projects Idaho-based Companies 2018 Leading Commodities: Phosphate rock, Sand and Gravel, Crushed Stone, Pb and Ag Idaho Non-fuel Mineral Production Idaho Non-fuel Mineral Production (USGS data) 1,400,000 1,200,000 1,000,000 800,000 600,000 000sof $ 400,000 200,000 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018P Metals $ Total $ Dec. 2014: Thompson Creek Mo on care and maintenance; large March 2017: Lucky Friday resource remains. miners go on strike. Metal prices (5-years) Co Au Mo: $ 9.70/lb. (LME, Platt’s, 11/20/2019) vs. >$ 11 at end of 2018. Ag Two World Class Mining Districts Coeur d’Alene District: Over 1.24 billion troy ounces Ag (38,568 metric tons) Pb, Zn, Cu, Sb Quartz-Siderite-Sulfide veins in PC Belt metasedimentary rocks Deep mines, ore extends vertically SE Phosphate District: Also over 100 years production Permian Phosphoria Formation Sedimentary apatite-rich black shale of regional extent Coeur d’Alene district (Silver Valley) Murray 2019 Active: Lucky Friday Galena Complex (inc. Coeur) Inactive, but resource in ground: Sunshine Bunker Hill – Zn, renegotiated lease Hecla Mining Company: Lucky Friday mine 2018 Sentinels of Safety 2019 production by salaried employees up Award by NMA (115,682 oz. -

Brochure: Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur D'alene Basin

Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin February 2013 EPA 910-K-13-003 he Silver Valley and the Coeur d’Alene For example, over 6,000 properties have been cleaned Basin are great places to live, work, and play. up in the Box and Upper and Lower Basin (see map). T Knowing the facts about our area will help Properties include residential, commercial, and public keep you and your family safe and healthy. Since the properties such as parks and school grounds. late 1800’s, the Silver Valley has been a major mining area and one of the largest silver producing areas of However, lead and other metals remain in areas like the world. Past mining practices left behind metals hillsides, some river beaches and floodplains, and other like lead and arsenic in the environment. recreational areas. Cleanup has been under way since the 1980s. This brochure suggests practical tips on how to further Together, we have made great progress in reducing reduce lead exposure and safely enjoy this beautiful risks. environment. Look inside for tips, to-do's, and resources. Facts About Lead • In our area, lead from past mining practices is typically found in: Why Lead soil on hillsides in the “Box” and around old mill sites in the Basin Poses a Risk soil on the floodplain and beaches along the South Fork and Lead is most dangerous to the Coeur d’Alene River young children, pregnant women, and unborn children. dirt tracked into vehicles or into the home from these areas soil underneath clean soil caps (usually 1 foot deep), under It can cause learning foundations and in dirt basements disabilities, behavioral problems and slower growth. -

A Silver Lining in the Silver Valley Idaho Bench-Bar Conference: Boise, Idaho

A Silver Lining in the Silver Valley Idaho Bench-Bar Conference: Boise, Idaho Prof. Clifford J. Villa University of New Mexico School of Law October 25, 2019 Disclaimer: Views expressed in this presentation are those of the presenter alone and do not necessarily represent official views of the United States, the State of New Mexico, or any government agency. The presenter gratefully acknowledges the contributions to this presentation from individuals including Bill Boyd, Curt Fransen, Rob Hanson, and Darrell Early. Framework: • The Silver Valley: 1883-1973 • The Box: 1973-1995 • The Basin: 1996-present 1883: Gold discovered in North Fork Coeur d’Alene Basin Prichard Creek (c.1883). Photo: PATRICIA HART & IVAN NELSON, MINING TOWN: THE PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF T.N. BARNARD AND NELLIE STOCKBRIDGE FROM THE COEUR D’ALENES The Silver Valley – 1884: Morning Mine established near Mullan, Idaho 1885: Bunker Hill mine staked by Noah Kellogg 1889: Union Pacific Railroad line arrives to serve local mines 1891: Hecla Mining Company founded The Silver Valley – Hecla Mine (1910), Burke, Idaho. Photo: PATRICIA HART & IVAN NELSON, MINING TOWN: THE PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF T.N. BARNARD AND NELLIE STOCKBRIDGE FROM THE COEUR D’ALENES The Silver Valley – 1890s: Mining unions vs. mining companies Wreckage of Bunker Hill mill (1899). Photo: PATRICIA HART & IVAN NELSON, MINING TOWN: THE PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF T.N. BARNARD AND NELLIE STOCKBRIDGE FROM THE COEUR D’ALENES The Silver Valley – 1903: Downstream farmers vs. upstream mines The Silver Valley – 1920s: Smelter construction / operation The Silver Valley – 1920s: Smoke easements / overflow easements The Silver Valley – 1920s: Smoke easements / overflow easements The Silver Valley – 1930: Luama v. -

Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur D'alene Basin

Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin # EPA 910-K-20-001 September 2020 The Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin are great places to live, work, and play. Knowing the facts about our area will help keep you and your family healthy. Past mining practices left behind large volumes of lead and other heavy metals in Basin soils. Since the 1980s, we have made great progress in reducing risks from the contamination. For example, over 7,100 properties have been cleaned up. Even so, lead and other metals remain in areas that have not been cleaned up. Read on for tips to limit exposure and safely enjoy this beautiful environment. Lead in our area z In our area, lead from past mining practices is often found in: o Soil on hillsides and around old mill sites. o Soil on the riverbanks and floodplains. o Soil tracked into vehicles or into homes from these areas. o Soil under clean soil caps, under foundations, and in the dirt floor of crawl spaces and cellars. o Dust in homes. z Lead paint can be present in homes built before 1978. Learn more at https://www.epa.gov/lead/protect-your-family-exposures-lead z Some toys and ceramics may contain lead. 1 Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin Lead Poses a Risk Lead is most dangerous to young children, pregnant women, and unborn children. It can cause learning disabilities, behavioral problems, and slower growth. Lead can pose a risk to adults, too, causing memory loss, irritability, high blood pressure, and muscle or joint pain. -

Exploration in Idaho 1997

EXPLORATION IN IDAHO -1997 V.S. Gillerman and E.M. Bennett Idaho Geological Survey For the first time in several years, Idaho's silver mines enjoyed a better year than the state's gold properties. By the end of 1997, silver prices were on the way up. However, gold and base metal prices were down, with the resulting toll on Idaho properties. Gold production in Idaho during 1997 totaled 7.44 t (239,433 oz.), a drop from the 1996 record of 10.8 t (347,470 oz.). (Note: The U.S. Geological Survey's 1996 Idaho gold production number reported in its statistical summary omitted the Beartrack production and is incorrect. The correct number, 10,801 kg, should be included in future Minerals Yearbooks.) Like last year, Meridian Gold's Beartrack Mine was the top producer in 1997, with 3.3 t (107,271 oz.) poured. Pegasus Gold's Black Pine Mine extracted 1.37 t (44,081 oz.) before its scheduled shutdown in December. Kinross Gold's DeLamar and Stone Cabin mines in Owyhee County produced 1.42 t (45,675 oz.). Dakota Mining's Stibnite Mine accounted for 472 kg (15,168 oz.). Ore reserves were exhausted at Black Pine, which opened in 1991. Reclamation efforts were under way at year's end. Hecla Mining's Grouse Creek operation in Custer County shut down in April due to errors in reserve calculations and disappointing production from the Sunbeam pit. Reclamation at Grouse Creek included pit recontouring and construction of a water treatment plant to prevent sediment from reaching the creek. -

Silver Valley People's Action Coalition Kellogg, Idaho “When You Live in a Community Like This, It Becomes Normal to See

FIGHTING FOR POLLUTION CLEANUP IN A COMPANY TOWN Silver Valley People’s Action Coalition Kellogg, Idaho “When you live in a community like this, it becomes normal to see one out of 10 kids that can't walk or can't concentrate. And not just kids, grownups. It becomes the norm; you get used to it." A city councilman and local businessman Barbara Miller Director Silver Valley Peoples Action Coalition P. O. Box 362 Kellogg, ID 83837 Phone: 208-784-8891 Fax: 208-784-8891 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nidlink.com/~paccrcco SUMMARY: Barbara Miller and a coalition of local activists address the environmental and health consequence of 100 years of mining in Idaho’s Silver Valley. They are up against the physical damage wrought by lead poisoning as well as community members’ deep reluctance to speak out against the mining companies that had such a hold on the community. Undaunted, Miller and her colleagues pursue the following goals: • Cleanup People’s Homes: Since discovering the presence of lead in people’s homes as well as is in the environment, the coalition expanded its cleanup demands. • Build Public Credibility: Using door-to-door surveys, meeting with civic groups, and disseminating information about the scope of the pollution and its impacts, the coalition maintains the momentum for cleanup. • Engage Groups, Including Government Agencies, Outside Of The Region: Once the coalition engaged Washington, going beyond the regional EPA office, it began to see results. • Address Public Health Impacts: By establishing a health clinic and research center, the coalition enables community residents to manage the devastating effects of lead poisoning. -

Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur D'alene Basin

# EPA 910-K-17-005 September 2017 Healthy Living in the Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin The Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene Basin are great places to live, work, and play. Knowing the facts about our area will help keep you and your family healthy. Past mining practices left behind large volumes of lead and other heavy metals. Since the 1980s, we have made great progress in reducing risks. For example, over 7,000 properties have been cleaned up. Even so, lead and other metals remain. Read on for tips to limit exposure and safely enjoy this beautiful environment. Lead in our Area • In our area, lead from past mining practices is often found in: ¾ Soil on hillsides and around old mill sites ¾ Soil on the river banks and floodplains ¾ Dirt tracked into vehicles or into homes from these areas ¾ Soil under clean soil caps, under foundations and in dirt basements ¾ Dust in homes • Lead paint can be present in homes built before 1978. Learn more at https://www.epa.gov/lead/protect-your-family-exposures-lead • Some toys and ceramics may contain lead. 1 Lead Poses a Risk Lead is most dangerous to young children, pregnant women, and unborn children. It can cause learning disabilities, behavioral problems and slower growth. Lead can pose a risk to adults, too, causing memory loss, irritability, high blood pressure and muscle or joint pain. Lead is taken into the body by swallowing lead-contaminated dirt or water, or by inhaling air contaminated by lead dust. ● Even small amounts of lead can harm a child -- even less than a quarter teaspoon of contaminated dust or soil. -

SHOSHONE COUNTY Idaho Opportunity Zone

Lorem ipsum SHOSHONE COUNTY Idaho Opportunity Zone OPPORTUNITY ZONE OVERVIEW WHAT’S IN THE ZONE? This zone includes the country runs 90 Access to Interstate 90 the communities of through the area. Kellogg, Wardner, Recreation including Silver Smelterville and The zone contains Mountain Ski Resort, Silver Rapids indoor water park, Silver Mountain Shoshone County. several historic Bike Park and a golf course Once home to the buildings and a number of parcels largest silver Shoshone County Airport processing facility in have been cleared or the world, it contains are in the process of a destination resort, being approved by North Idaho College campus Silver Mountain, with the Idaho in Kellogg skiing and mountain Department of biking. The trail of Environmental the Coeur d'Alenes Quality for which ranks as one redevelopment. of the top trails in 1 32 INVESTMENT SITES 1. 163 E. Commerce Drive, Smelterville 13.9 acre mill site with oce building, storage facility and 14,900 sq. ft. planner building. 2. 8 McKinley Avenue, Kellogg 10,000 sq.ft. mixed-use retail oce with loading dock, basement and apartment. 3. 210 McKinley Avenue, Kellogg Two story building with retail/restaurant space and eight lodging rooms. CENSUS TRACT 16079960300 LOCAL PRIORITIES INVESTMENTS Housing is a top priority for this The three communities in this Quick Facts opportunity zone. The county’s zone are a part of a Superfund About proximity to Coeur d’Alene has site. This designation creates created a rise in the real estate unique grant and redevelopment Shoshone market, and multi-family funding opportunities. dwellings and newer residential Infrastructure and recreational County, Idaho homes are in short supply. -

Reuse and the Benefit to Community Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site

Reuse and the Benefit to Community Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site Introduction The Coeur d’Alene Basin in northern Idaho is one of the largest historic mining districts in the world. Over 100 years of commercial mining, milling and smelting resulted in the widespread contamination of soil, sediment, groundwater and surface water in the area now known as the Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex Superfund site. Extensive cooperation and collaboration among the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (IDEQ), the Idaho Panhandle Health District (PHD), and other local and state agencies resulted in the cleanup and restoration of over 7,000 properties. The site’s unique and comprehensive institutional control program (ICP) has enabled continued use and new development across the site – providing a framework in which regulatory agencies and the community can approach cleanups, manage risks, and address community and developer concerns. The ongoing, open communication and innovative thinking of site stakeholders has resulted in the remarkable transformation of this once-contaminated industrial site into a revitalized area built on a shared vision of a better future. Superfund site restoration and reuse can revitalize local economies with jobs, new businesses, tax revenues and local spending. Cleanup may also take place while active land uses remain on site. Today, the site supports a wide range of commercial, industrial, public service, residential and recreational reuses. The site is now home to the Silver Mountain Resort, a year-round tourist destination that offers recreation opportunities – including skiing, golf, biking and an indoor water park – to locals and visitors. -

Shoshone County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazards Mitigation Plan

Shoshone County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazards Mitigation Plan Shoshone County, with the Cities of Kellogg, Mullan, Osburn, Pinehurst, Smelterville, Wallace & Wardner August 24, 2009 City of Smelterville Elevation 2,234 ft This effort developed with the Shoshone County Multi-Jurisdictional Hazards Mitigation Planning Committee and environmental and regional planning services provided by: TerraGraphics Environmental Engineering, Inc. 108 West Idaho Ave. Kellogg, Idaho 83837 Table of Contents 1. Adoptions, Promulgations, and Acceptance ..........................................................................1 1.1. FEMA Region X Letter of Approval ...............................................................................1 1.2. Authorship and Conveyance .........................................................................................1 1.3. Shoshone Board of County Commissioners Adoption ..................................................2 1.4. Kellogg City Council Adoption.......................................................................................3 1.5. Mullan City Council Adoption ........................................................................................4 1.6. Osburn City Council Adoption .......................................................................................5 1.7. Pinehurst City Council Adoption....................................................................................6 1.8. Smelterville City Council Adoption ................................................................................7 -

Bunker Hill Mining & Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site Northern Idaho

SITE REDEVELOPMENT PROFILE Superfund Bunker Hill Mining & Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site Redevelopment Initiative Northern Idaho The Silver Mountain Resort and the Kellogg skyline. (Source: EPA) Site Location: Northern Idaho, east of the city of Coeur d’Alene Size: Over 1,500 square miles Existing Site Infrastructure: All major types of infrastructure are located on site. Current Site Uses: The site supports a wide range of commercial, industrial, public service, residential and recreational uses. Use Restrictions: The Idaho Panhandle Health District (Idaho PHD) manages the site’s unique and comprehensive institutional control program (ICP). The ICP ensures the compatibility of future uses with the remedy and helps maintain protective barriers across the site. It regulates and provides assistance for all construction projects within designated boundaries. No homes or businesses are built on site without ICP involvement. Surrounding Population: The site includes mining-contaminated areas in the Coeur d’Alene River corridor, adjacent floodplains, downstream water bodies, tributaries and fill areas as well as the 21-square- mile Bunker Hill Box (referred to as “the Box”), which surrounds the area of historic smelting operations. Operable unit 1 (OU1) includes populated areas of the Box. OU2 includes non-populated areas of the Box. OU3 addresses mining-related contamination in the broader Coeur d’Alene Basin. In total, the site spans 1,500 square miles and 166 river miles, across several counties. The Box is located in Shoshone County, Idaho. About 12,500 people live in Shoshone County. The Coeur d’Alene Basin in northern Idaho is one of the largest historic mining districts in the world.