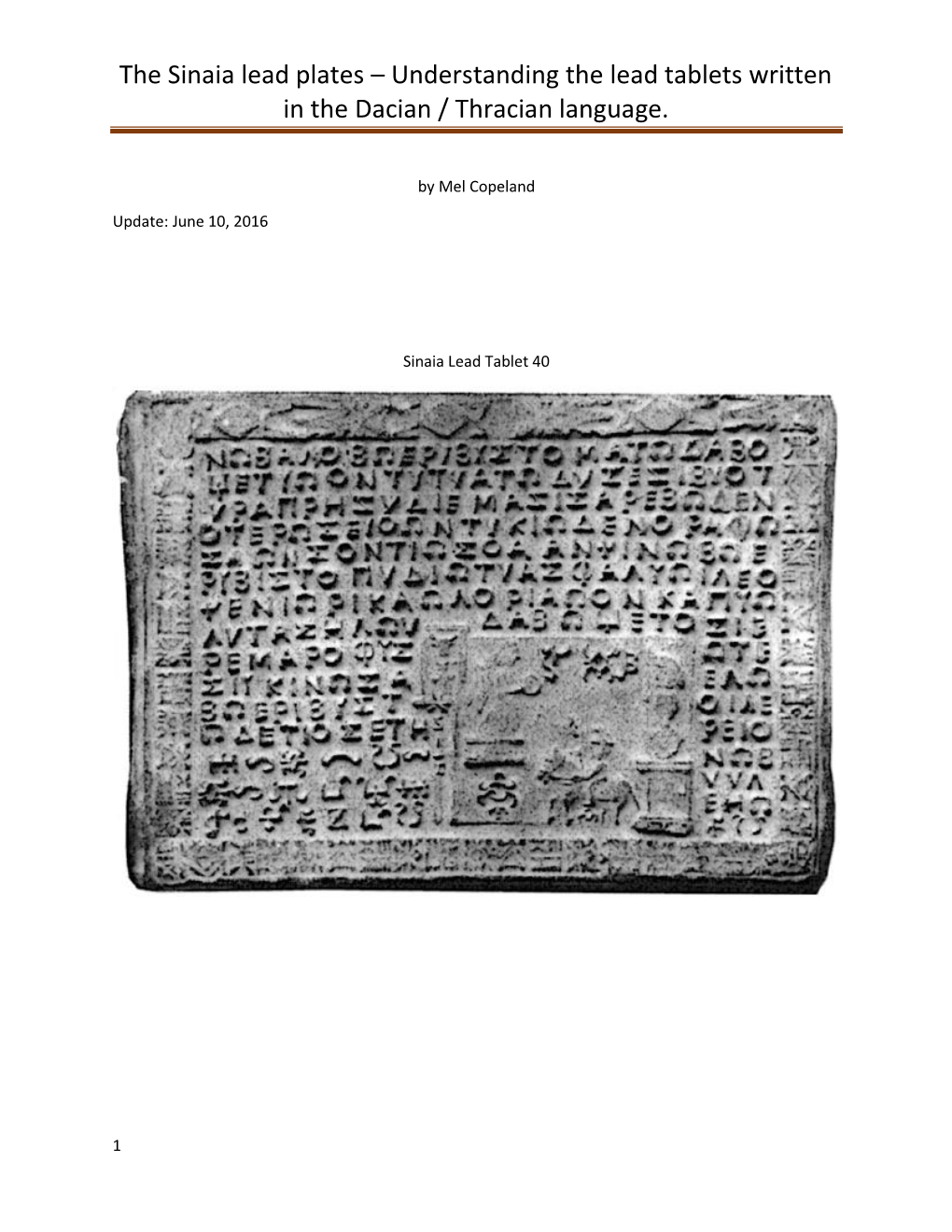

Understanding the Lead Tablets Written in the Dacian / Thracian Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Thracians and Phrygians

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents i List of Figures List of Tables m Editor's Note vi vii Introduction on behalf of Centre for Research and Assessment of the Historic Environment (TAÇDAM) at Middle East Technical University Ankara, TURKEY AssocProf.Dr. Numan TUNA, the Director Introduction on behalf of the Institute of Thracology Sofia, BULGARIA Assoc.Prof.Dr. Kiril YORDANOV, the Director and Dr. Maya VASSILEVA Opening Speech on behalf of Scientific Institutions Prof .Dr. Machteld J. MELLINK Thracian-Phrygian Cultural Zone 13 Maya VASSILEVA Sofia, BULGARIA Megaliths in Thrace and Phrygia 19 Valeria FOL Sofia, BULGARIA Early Iron Age in Eastern Thrace and the Megalithic Monuments 29 Mehmet ÔZDOÔAN Istanbul, TURKEY Some Connections Between the Northern Thrace and Asia Minor During the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age 41 Attila LASZLO Ia§i, ROMANIA Bryges and Phrygians: Parallelism Between the Balkans and Asia Minor Through Archaeological, Linguistic and Historical Evidence 45 Eleonora PETROVA Skopije, MACEDONIA Sabas/Sabazios/Sabo 55 Alexander FOL Sofia, BULGARIA Burial Rites in Thrace and Phrygia 61 Roumyana GEORGIEVA Sofia, BULGARIA Die Ausgrabung der Megalithischen Dolmenanlage in Lalapasa 65 MuratAKMAN Istanbul. TURKEY The Early Iron Age Settlement on Biiyukkaya, Bogazkoy: First Impressions 71 Jurgen SEEHER German Institute of Archaeology, Istanbul The Early Iron Age at Gordion: The Evidence from the Yassihoyiik Stratigraphie Sequence 79 Robert C. HENRICKSON and Mary M. VOIGT Philadelphia, USA Roman Phrygia 107 D.H. FRENCH Waterford, UK Phrygia: Linguistics and Epigraphies HI Petar DIMITROV Sofia, BULGARIA Phrygian and the Southeast European Namebund 115 Adrian PORUCIUC lasi, ROMANIA Une Inscription en Langue Inconnue 119 Catherine BRIXHE et Thomas DREW-BEAR Lyon, FRANCE Conservation and Reconstruction of Phrygian Chariot Wheels from Mysia 131 Hande KÔKTEN Istanbul, TURKEY Microstructural Studies on Some Phrygian Metallic Objects 147 Macit ÔZENBAS and Lèvent ERCANLI Ankara, TURKEY Panel Discussions 157. -

Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:2 (1983:Summer) P.105

SHAPIRO, H. A., Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 24:2 (1983:Summer) p.105 Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians H A. Shapiro HE AMAZONS offer a remarkable example of the lacunose and T fragmented state of ancient evidence for many Greek myths. For while we hear virtually nothing about them in extant litera ture before the mid-fifth century, they are depicted in art starting in the late eighth! and are extremely popular, especially in Attica, from the first half of the sixth. Thus all we know about the Greeks' con ception of the Amazons in the archaic period comes from visual rep resentations, not from written sources, and it would be hazardous to assume that various 'facts' and details supplied by later writers were familiar to the sixth-century Greek. The problem of locating the Amazons is a good case in point. Most scholars assume that Herakles' battle with the Amazons, so popular on Attic vases, took place at the Amazon city Themiskyra in Asia Minor, on the river Thermodon near the Black Sea, where most ancient writers place it.2 But the earliest of these is Apollodoros (2.5.9), and, as I shall argue, alternate traditions locating the Ama zons elsewhere may have been known to the archaic vase-painter and viewer. An encounter with Amazons figures among the exploits of three important Greek heroes, and each story entered the Attic vase painters' repertoire at a different time in the course of the sixth century. First came Herakles' battle to obtain the girdle of Hippolyte (although the prize itself is never shown), his ninth labor. -

Confrontation in Karabakh: on the Origin of the Albanian Arsacids Dynasty

Voice of the Publisher, 2021, 7, 32-43 https://www.scirp.org/journal/vp ISSN Online: 2380-7598 ISSN Print: 2380-7571 To Whom Belongs the Land? Confrontation in Karabakh: On the Origin of the Albanian Arsacids Dynasty Ramin Alizadeh1*, Tahmina Aslanova2, Ilia Brondz3# 1Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences (ANAS), Baku, Azerbaijan 2Department of History of Azerbaijan, History Faculty, Baku State University (BSU), Baku, Azerbaijan 3Norwegian Drug Control and Drug Discovery Institute (NDCDDI) AS, Ski, Norway How to cite this paper: Alizadeh, R., As- Abstract lanova, T., & Brondz, I. (2021). To Whom Belongs the Land? Confrontation in Kara- The escalation of the Karabakh conflict during late 2020 and the resumption bakh: On the Origin of the Albanian Arsa- of the second Karabakh War—as a result of the provocative actions by the cids Dynasty. Voice of the Publisher, 7, Armenian government and its puppet regime, the so-called “Artsakh Repub- 32-43. lic”—have aroused the renewed interest of the scientific community in the https://doi.org/10.4236/vp.2021.71003 historical origins of the territory over which Azerbaijan and Armenia have Received: December 6, 2020 been fighting for many years. There is no consensus among scientific experts Accepted: March 9, 2021 on this conflict’s causes or even its course, and the factual details and their Published: March 12, 2021 interpretation remain under discussion. However, there are six resolutions by Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and the United Nations Security Council that recognize the disputed territories as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. Azerbaijan’s national territory. This paper presents the historical, linguistic, This work is licensed under the Creative and juridical facts that support the claim of Azerbaijan to these territories. -

The Egyptians and the Scythians in Herodotus' Histories

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2011 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2011 The Old and the Restless: The Egyptians and the Scythians in Herodotus' Histories Robert J. Hagan Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2011 Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Hagan, Robert J., "The Old and the Restless: The Egyptians and the Scythians in Herodotus' Histories" (2011). Senior Projects Spring 2011. 10. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2011/10 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Old and the Restless: The Egyptians and the Scythians in Herodotus’ Histories Senior Project Submitted to Division of Language and Literature of Bard College by Robert Hagan Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2011 2 Acknowledgments On the completion of this sometimes challenging, but always rewarding project, I thank my family and friends for their support throughout the year. Thanks also go to the classics department at Bard, including Bill Mullen and Thomas Bartscherer for their help and advice, as well as one dearly needed extension. -

Diachronie Et Synchronie (Coliga) Colloque International 7-9 Avril 2021

Contacts linguistiques en Grèce ancienne : diachronie et synchronie (CoLiGA) Colloque international 7-9 avril 2021 Rostislav Oreshko Université de Leyde Phrygian and the Early History of Greek Dialects Although the evidence for Phrygian is scarce – several dozens of quite short texts plus about 300 graffiti dating to the 8th-5th c. BC and a hundred of mostly formulaic Neo-Phrygian inscriptions dated to 2nd- 3rd c. AD – it is clear that Phrygian is the closest linguistic relative of Greek (cf. de Lamberterie 2013, Ligorio-Lubotsky 2018, Obrador-Cursach 2020). Moreover, their affinity is not simply a linguistic abstraction: numerous indications suggest that the Phrygians and the Greeks were in a close geographical contact possibly until as late as the early post-Mycenaean period (12th-11th centuries BC). This is implied, for instance, by literary evidence on the European relatives of the Phrygians, Βρίγες (Hdt. 7.73 or Str. 7.3.2) or Βρύγοι (Hdt. 6.45), who were the neighbours of the Macedonians and whose areal might have extended as far west as Epidamnos/Dyrrachium (cf. Appian, BC 2.6.39); by the titles vanak and *lavagetas attested with Midas in OPhr. inscription M-01a, which have a distinct Mycenaean sounding; or by archaeological evidence for the migration from the Balkans to Anatolia at the end of the 2nd millennium BC. The evidence would not even be incompatible with the idea that early Greek and ‘proto-Phrygian’ once formed a dialect continuum. Seen in this perspective, Phrygian evidence is potentially important for understanding the dialectal situation in the northern parts of Greece as in the late 2nd millennium BC as, by extension, in the later period. -

Continuity of the Late La Tène Warrior Elite in the Early Roman Period in South-Eastern Pannonia

BUFM 79, Dizdar, Radman-Livaja, „Continuity of the Late La Tène warrior elite“, 209–227 209 Marko Dizdar, Ivan Radman-Livaja Continuity of the Late La Tène warrior elite in the Early Roman Period in south-eastern Pannonia Keywords: warrior elite / Late La Tène Period / the warrior elite of the Scordisci as allies. After Roman conquest / southeastern Pannonia / Scor- the establishment of Roman power the burials disci / warrior equipment / prestige goods of the warrior elite were continued regardless of Schlagwörter: Kriegerelite / Spätlatènezeit / Römi- the appearance of a new political-administrative sche Eroberung / Südostpannonien / Skordisker / government because members of the local aris- Waffenausstattung / Prestigegüter tocracy were entrusted with the defence of the limes. They continued to be buried, in accord- Summary ance with their ancient customs, together with During the Roman conquest and the ensuing their personal weapons, now of Roman origin, stabilization in the late 1st c. BC and 1st c. AD and also continued to offer provisions to the the most prominent position in the society of deceased that included numerous imported the Scordisci, Taurisci and those of autochtho- goods together with certain pottery forms of nous Pannonian communities was held by local local origin thus testifying to their keeping of warrior elites. Their roots can be recognised in their previously acquired status. Thus, Rom- important social and economic transformations anisation was implemented by the ruling social that occurred in the first half and the middle of class, the warrior elite being able to preserve the 2nd c. BC. The burials of the warrior elite of some of their previously attained positions and the LT D1 phase (second half of the 2nd and early to remain in its original area. -

Illyrian Policy of Rome in the Late Republic and Early Principate

ILLYRIAN POLICY OF ROME IN THE LATE REPUBLIC AND EARLY PRINCIPATE Danijel Dzino Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics University of Adelaide August 2005 II Table of Contents TITLE PAGE I TABLE OF CONTENTS II ABSTRACT V DECLARATION VI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VII LIST OF FIGURES VIII LIST OF PLATES AND MAPS IX 1. Introduction, approaches, review of sources and secondary literature 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Rome and Illyricum (a short story) 2 1.3 Methodology 6 1.4.1 Illyrian policy of Rome in the context of world-system analysis: Policy as an interaction between systems 9 1.4.2 The Illyrian policy of Rome in the context of world-system analysis: Working hypothesis 11 1.5 The stages in the Roman Illyrian relationship (the development of a political/constitutional framework) 16 1.6 Themes and approaches: Illyricum in Roman historiography 18 1.7.1 Literature review: primary sources 21 1.7.2 Literature review: modern works 26 2. Illyricum in Roman foreign policy: historical outline, theoretical approaches and geography 2.1 Introduction 30 2.2 Roman foreign policy: Who made it, how and why was it made, and where did it stop 30 2.3 The instruments of Roman foreign policy 36 2.4 The place of Illyricum in the Mediterranean political landscape 39 2.5 The geography and ethnography of pre-Roman Illyricum 43 III 2.5.1 The Greeks and Celts in Illyricum 44 2.5.2 The Illyrian peoples 47 3. The Illyrian policy of Rome 167 – 60 BC: Illyricum - the realm of bifocality 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Prelude: the making of bifocality 56 3.3 The South and Central Adriatic 60 3.4 The North Adriatic 65 3.5 Republican policy in Illyricum before Caesar: the assessment 71 4. -

Economic Role of the Roman Army in the Province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE of EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY in POZNAŃ

Economic role of the Roman army in the province of Lower Moesia (Moesia Inferior) INSTITUTE OF EUROPEAN CULTURE ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ ACTA HUMANISTICA GNESNENSIA VOL. XVI ECONOMIC ROLE OF THE ROMAN ARMY IN THE PROVINCE OF LOWER MOESIA (MOESIA INFERIOR) Michał Duch This books takes a comprehensive look at the Roman army as a factor which prompted substantial changes and economic transformations in the province of Lower Moesia, discussing its impact on the development of particular branches of the economy. The volume comprises five chapters. Chapter One, entitled “Before Lower Moesia: A Political and Economic Outline” consti- tutes an introduction which presents the economic circumstances in the region prior to Roman conquest. In Chapter Two, entitled “Garrison of the Lower Moesia and the Scale of Militarization”, the author estimates the size of the garrison in the province and analyzes the influence that the military presence had on the demography of Lower Moesia. The following chapter – “Monetization” – is concerned with the financial standing of the Roman soldiery and their contri- bution to the monetization of the province. Chapter Four, “Construction”, addresses construction undertakings on which the army embarked and the outcomes it produced, such as urbanization of the province, sustained security and order (as envisaged by the Romans), expansion of the economic market and exploitation of the province’s natural resources. In the final chapter, entitled “Military Logistics and the Local Market”, the narrative focuses on selected aspects of agriculture, crafts and, to a slightly lesser extent, on trade and services. The book demonstrates how the Roman army, seeking to meet its provisioning needs, participated in and contributed to the functioning of these industries. -

Univerza V Mariboru Filozofska Fakulteta

UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA Oddelek za anglistiko in amerikanistiko DIPLOMSKO DELO Iva Starc Maribor, 2011 UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA Oddelek za anglistiko in amerikanistiko Diplomsko delo INDOEVROPEJCI IN BESEDE SKUPNEGA IZVORA INDOEVROPSKIH JEZIKOV Graduation thesis INDO-EUROPEANS AND WORDS OF COMMON ORIGINS FROM THE INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES Mentorica: Kandidatka: red. prof. dr. Dunja Jutronić Iva Starc Maribor, 2011 Lektorici: Maja Schweiger, profesorica angleškega in nemškega jezika Maja Malnarič, profesorica slovenskega in nemškega jezika ZAHVALA Zahvaljujem se mentorici, red. prof. dr. Dunji Jutronić, za strokovno pomoč pri izdelavi diplomskega dela. Iskrena hvala družini in prijateljem za vso pomoč in podporo v času študija. I Z J A V A Podpisana Iva Starc, rojena 22.08.1987 študentka Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Mariboru, smer angleški jezik s književnostjo in sociologija, izjavljam, da je diplomsko delo z naslovom Indo-Europeans and words of common origins from the Indo-European languages pri mentorici red. prof. dr. Dunji Jutronić, avtorsko delo. V diplomskem delu so uporabljeni viri in literatura korektno navedeni; teksti niso prepisani brez navedbe avtorjev. _______________________ Maribor, 2011 POVZETEK Indoevropejci predstavljajo najštevilčnejšo jezikovno družino sveta. Zaradi svoje številčnosti in raznolikosti so skozi zgodovino pomembno vplivali na oblikovanje današnjega sveta. Mnogi strokovnjaki skušajo pojasniti njihov izvor in način, po katerem so živeli, a jih pri tem ovira predvsem primanjkljaj dokazov. V prvem delu diplomske naloge so bili opisani indoevropski jeziki in narodi, ki uporabljajo te jezike v Evropi in Aziji. Tako kot številna strokovna dela, se je tudi diplomsko delo poskušalo najti domovino Indoevropejcev in poti po katerih je potekala njihova razselitev.