Foreign Direct Investment Strategies by Multinational Automotive Suppliers: a New Link Between Outsourcing and Industry Concentration in Turbulent Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Prospectus

Nexteer Automotive Group Limited 耐世特汽車系統集團有限公司 (Incorporated under the laws of the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code : 01316) Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Sponsors Financial Advisor >cfYXc F]]\i`e^ IMPORTANT: If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this Prospectus, you should seek independent professional advice. Nexteer Automotive Group Limited 耐世特汽車系統集團有限公司 (Incorporated under the laws of the Cayman Islands with limited liability) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares in the Global Offering : 720,000,000 Shares (subject to the Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 72,000,000 Shares (subject to adjustment) Number of International Offer Shares : 648,000,000 Shares (subject to adjustment and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$3.57 per Hong Kong Offer Share, plus brokerage of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.003%, and Hong Kong Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars and subject to refund) Nominal value : HK$0.10 per Share Stock code : 01316 Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Sponsors Financial Advisor Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this Prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Prospectus. A copy of this Prospectus, having attached thereto the documents specified in “Appendix VI — Documents Delivered to the Registrar of Companies and Available for Inspection,” has been registered by the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by Section 342C of the Companies Ordinance (Chapter 32 of the Laws of Hong Kong). -

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions

Aerospace, Defense, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions (January 1993 - April 2020) Huntington BAE Spirit Booz Allen L3Harris Precision Rolls- Airbus Boeing CACI Perspecta General Dynamics GE Honeywell Leidos SAIC Leonardo Technologies Lockheed Martin Ingalls Northrop Grumman Castparts Safran Textron Thales Raytheon Technologies Systems Aerosystems Hamilton Industries Royce Airborne tactical DHPC Technologies L3Harris airport Kopter Group PFW Aerospace to Aviolinx Raytheon Unisys Federal Airport security Hydroid radio business to Hutchinson airborne tactical security businesses Vector Launch Otis & Carrier businesses BAE Systems Dynetics businesses to Leidos Controls & Data Premiair Aviation radios business Fiber Materials Maintenance to Shareholders Linndustries Services to Valsef United Raytheon MTM Robotics Next Century Leidos Health to Distributed Energy GERAC test lab and Technologies Inventory Locator Service to Shielding Specialities Jet Aviation Vienna PK AirFinance to ettain group Night Vision business Solutions business to TRC Base2 Solutions engineering to Sopemea 2 Alestis Aerospace to CAMP Systems International Hamble aerostructure to Elbit Systems Stormscope product eAircraft to Belcan 2 GDI Simulation to MBDA Deep3 Software Apollo and Athene Collins Psibernetix ElectroMechanical Aciturri Aeronautica business to Aernnova IMX Medical line to TransDigm J&L Fiber Services to 0 Knight Point Aerospace TruTrak Flight Systems ElectroMechanical Systems to Safran 0 Pristmatic Solutions Next Generation 911 to Management -

Merger Decision

EN Case No IV/M.768 - Lucas / Varity Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 11/07/1996 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 396M0768 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES . Brussels, 11.07.1996 PUBLIC VERSION MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION Registered letter with advice of delivery: To the notifying parties Dear Sirs, Subject : Case No IV/M.768 - LUCAS / VARITY Notification of 10.6.1996 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 1. The companies Lucas Industries plc, Solihull/UK ("Lucas"), and Varity Corporation, Buffalo, New York/USA ("Varity"), notified that they intend to enter into a full merger. Under the terms of the merger a new UK holding company, to be known as LucasVarity plc, will be created. The Lucas shareholders will own about 62% and the Varity shareholders about 38% of the new merged business. 2. After the examination of the notification, the Commission has concluded that the notified operation falls within the scope of application of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 ("Merger Regulation") and does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the common market and with the functioning of the EEA Agreement. I. THE PARTIES 3. Lucas designs, manufactures and sales advanced technology systems and components for the automotive and aerospace industry, in particular braking systems, diesel fuel injection systems as well as electrical and electronic systems. In its last business year, ended July 1995, the company had a worldwide turnover of about ECU 3.5 billion, about ECU 2.5 billion of it was generated within the Community. -

World Automotive Aftermarket

Study Publication Date: April 2001 Freedonia Industry Study #1408 Price: $4,500 Pages: 408 World Automotive Aftermarket World Automotive Aftermarket, a new study from The Freedonia Group, provides you with an in-depth analysis of the major trends in the world automotive aftermarket and the outlook for product segments -- critical informa- tion to help you with strategic planning. This brochure gives you an indication of the scope, depth and value of Freedonia's new study, World Automo- tive Aftermarket. Ordering information is included on the back page of the brochure. Brochure Table of Contents Study Highlights ............................................................................... 2 Study Table of Contents and List of Tables and Charts ................... 4 Sample Pages and Tables from: Market Environment.................................................... 6 World Supply and Demand.......................................... 7 Supply and Demand by Country and Region............... 8 Industry Structure ........................................................ 9 Company Profiles ...................................................... 10 List of Companies Profiled ........................................ 11 Forecasting Methodology ............................................................... 12 About the Company ....................................................................... 13 Advantages of Freedonia Reports ................................................... 13 About Our Customers ................................................................... -

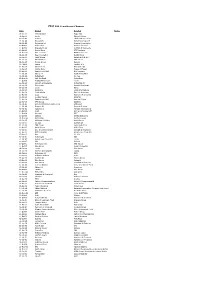

BMW of North America, LLC NJ ""K"" Line America, Inc. VA 1199

The plan sponsors listed below have at least one application for the Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS) program in an "Approved" status for a plan year ending in 2010 as of February 4, 2011. The state listed for each sponsor is the state provided by the sponsor on the application for the subsidy. This state may, or may not, be where the majority of the plan sponsor's retirees reside or where the plan sponsor is headquartered. This list will be updated periodically. Plan Plan Sponsor Business Name Sponsor State : BMW of North America, LLC NJ ""K"" Line America, Inc. VA 1199 SEIU Greater New York Benefit Fund NY 1199 SEIU National Benefit Fund NY 3M Company MN 4th District IBEW Health Fund WV A-C RETIREES' VOLUNTARY BENFITS PLAN WI A. DUDA & SONS, INC. FL A. SCHULMAN, INC OH A. T. Massey Coal Company, Inc. VA A&E Television Networks NY AAA EAST PENN PA AARP DC ABB Inc. CT Abbott Laboratories IL Abbott Pharmaceuticals PR Ltd. PR Acadia Parish School Board LA Accenture LLP IL Accuride Corporation IN ACF Industries LLC MO ACGME IL Acton Health Insurance Trust MA Actuant Corporation WI Adirondack Central School NY Administrative Office of the Pennsylvania Courts PA Adventist Risk Management MD Advisory Services OH AEGON USA, Inc. IA AFL-CIO Health and Welfare Trust DC AFSCME DC AFSCME Council 31 IL afscme d.c. 47 health & welfare fund PA AFSCME District Council 33 Health and Welfare Plan PA AFTRA Health Fund NY AGC FLAT GLASS NORTH AMERICA INC TN Page 1 AGC-IUOE Local 701 Health & Welfare Trust Fund WA AGCO Corporation GA Agilent Technologies, Inc. -

Developing an Eastern Cape Auto Sector Strategy

DEVELOPING AN EASTERN CAPE AUTO SECTOR STRATEGY A REPORT FOR THE EASTERN CAPE SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONSULTATIVE COUNCIL prepared by: Ian Russell This Report has been prepared at the request of the ECSECC, and is intended only for this purpose. March 2006 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report is: • To describe and analyse the historical performance of the Automotive sector of the Eastern Cape economy and to identify current trends • To identify its growth and labour absorption potential • To identify key constraints or blockages • To identify key infrastructural blockages and constraints and to make recommendations on how Government and stakeholders can address the constraints / blockages in a more systematic and pragmatic way A significant amount of space is devoted to the global industry, its relationships and the inter-relationships between vehicle manufacturers (OEMs) and component suppliers. This has been done because the investment decisions internationally, and this is equally applicable to South Africa, are increasingly being driven by global considerations. These decisions are often, in turn, motivated by OEMs, with the appropriate supplier investments following. Further, the significant rationalisation taking place globally is resulting in a reduction in the number of OEMs, suppliers and model platforms, each of which will have repercussions in all automotive-producing countries. A proper understanding of these complex global trends is essential background to any approach to OEMs or component suppliers for investment. It is important, therefore, to realise that in attracting new investment to a country or a region, it is unlikely that a component supplier will set up a manufacturing base without prior assurance of OEM business, at least in the local market or for export volumes. -

Case No IV/M.1462 - TRW / LUCAS VARITY

EN Case No IV/M.1462 - TRW / LUCAS VARITY Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 11/03/1999 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 399M1462 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 11-03-1999 In the published version of this decision, some PUBLIC VERSION information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets MERGER PROCEDURE and other confidential information. The ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. to the notifying party Dear Sirs, Subject: Case No IV/M. 1462 - TRW/LucasVarity Notification of 10 February 1999 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 4064/89 1. On 10 February 1999, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 1 by which TRW Inc., a US company, will acquire sole control of LucasVarity plc, a company incorporated in the United Kingdom. 2. After examining the notification, the Commission has concluded that the notified concentration falls within the scope of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 and does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the common market and with the functioning of the EEA Agreement. I. THE PARTIES 3. TRW Inc. (“TRW”) is a US company based in Cleveland, Ohio. -

Modernization of the Czech Air Force

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2001-06 Modernization of the Czech Air Force Vlcek, Vaclav. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/10888 This publication is a work of the U.S. Government as defined in Title 17, United States Code, Section 101. Copyright protection is not available for this work in the United States. Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS MODERNIZATION OF THE CZECH AIR FORCE by Vaclav Vlcek June 2001 Thesis Advisor: Raymond Franck Associate Advisor: Gregory Hildebrandt Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 20010807 033 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMBNo. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2001 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE : MODERNIZATION OF THE CZECH AIR FORCE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) Vaclav VIcek 8. PERFORMING 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) ORGANIZATION REPORT Naval Postgraduate School NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. -

Modernization of the Czech Air Force

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2001-06 Modernization of the Czech Air Force. Vlcek, Vaclav. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/10888 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS MODERNIZATION OF THE CZECH AIR FORCE by Vaclav Vlcek June 2001 Thesis Advisor: Raymond Franck Associate Advisor: Gregory Hildebrandt Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 20010807 033 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMBNo. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2001 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE : MODERNIZATION OF THE CZECH AIR FORCE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) Vaclav VIcek 8. PERFORMING 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) ORGANIZATION REPORT Naval Postgraduate School NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING / MONITORING N/A AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. -

FTSE 100 Constituent History Updated

FTSE 100 Constituent Changes Date Added Deleted Notes 19-Jan-84 CJ Rothschild Eagle Star 02-Apr-84 Lonrho Magnet Sthrns. 02-Jul-84 Reuters Edinburgh Inv. Trust 02-Jul-84 Woolworths Barrat Development 19-Jul-84 Enterprise Oil Bowater Corporation 01-Oct-84 Willis Faber Wimpey (George) 01-Oct-84 Granada Group Scottish & Newcastle 01-Oct-84 Dowty Group MFI Furniture 04-Dec-84 Brit. Telecom Matthey Johnson 02-Jan-85 Dee Corporation Dowty Group 02-Jan-85 Argyll Group Berisford (S.& W.) 02-Jan-85 MFI Furniture RMC Group 02-Jan-85 Dixons Group Dalgety 01-Feb-85 Jaguar Hambro Life 01-Apr-85 Guinness (A) Enterprise Oil 01-Apr-85 Smiths Inds. House of Fraser 01-Apr-85 Ranks Hovis McD. MFI Furniture 01-Jul-85 Abbey Life Ranks Hovis McD. 01-Jul-85 Debenhams I.C. Gas 06-Aug-85 Bnk. Scotland Debenhams 01-Oct-85 Habitat Mothercare Lonrho 02-Jan-86 Scottish & Newcastle Rothschild (J) 08-Jan-86 Storehouse Habitat Mothercare 08-Jan-86 Lonrho B.H.S. 01-Apr-86 Wellcome EXCO International 01-Apr-86 Coats Viyella Sun Life Assurance 01-Apr-86 Lucas Harrisons & Crosfield 01-Apr-86 Cookson Group Ultramar 21-Apr-86 Ranks Hovis McD. Imperial Group 22-Apr-86 RMC Group Distillers 01-Jul-86 British Printing & Comms. Corp Abbey Life 01-Jul-86 Burmah Oil Bank of Scotland 01-Jul-86 Saatchi & S. Ferranti International 01-Oct-86 Bunzl Brit. & Commonwealth 01-Oct-86 Amstrad BICC 01-Oct-86 Unigate Smiths Industries 09-Dec-86 British Gas Northern Foods 02-Jan-87 Hillsdown Holdings Argyll Group 02-Jan-87 I.C. -

Dr. Rob Smith, Senior Vice President, General Manager, Europe, Africa and Middle East

Feb 4, 2015, 7:00:00 PM Dr. Rob Smith, Senior Vice President, General Manager, Europe, Africa and Middle East Dr. Rob Smith is Senior Vice President and General Manager, Europe, Africa and Middle East. In this role, Dr. Smith is responsible for reinforcing AGCO’s leading market position in Europe and further expanding the company’s manufacturing footprint in Eastern Europe, Africa and Middle East. In particular, he leads AGCO’s efforts in developing the markets of Russia and Africa where AGCO sees significant growth potential in the agricultural equipment sector. Dr. Smith and his team are also responsible for improving AGCO’s distribution coverage and local assembly presence to leverage this immense growth potential. Dr. Smith has extensive international management experience and most recently was the Vice President & General Manager of the global Engine Components Division for TRW Automotive – one of the world’s largest automotive suppliers. He also was the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of TRW Automotive GmbH. Prior to this, Dr. Smith served as Vice President of the Global Automotive Division at Tyco Electronics, and Vice President & General Manager of the Aftermarket Parts and Material Repair and Overhaul business at Bombardier Transportation. Prior to 2001 he worked in various operations and supply chain roles in the global automotive industry with LucasVarity PLC, Lucas Industries PLC and BMW. Rob began his career as a Combat Engineer Officer in the United States Army. Dr. Smith earned his Bachelor of Science in Engineering from Princeton University followed by an MBA from the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School of Business. -

Aerospace, Defence, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions

Aerospace, Defence, and Government Services Mergers & Acquisitions - European (January 1993 - April 2020) BAE L3Harris Rolls- Airbus Hensoldt Boeing Cobham Dassault Elbit General Dynamics GE GKN Honeywell Indra Kongsberg Leonardo Lockheed Martin Meggitt Northrop Grumman Rheinmetall Saab Safran Thales Ultra Raytheon Technologies Systems Aviation Systems Sistemas Technologies Royce Electronics Airborne tactical PFW Aerospace to Aviolinx Raytheon Kopter Group Atmos Sistemas Advent Hydroid to Huntington Airport security radio business to Hutchinson Bombardier C Series airborne tactical Leonardo&Codemar businesses to Leidos Vector Launch Otis & Carrier businesses BAE Systems ALP stake [25%] radios business Int’l Ingalls Industries JV [51%] Controls & Data TCS EW business to to Shareholders IE Asia-Pacific Sistemas Services to Valsef Telemus United Raytheon MTM Robotics buyout Jet Aviation Vienna Distributed Energy GERAC test lab and PK AirFinance to Informaticos Abiertas Night Vision business Rheinmetall MAN Base2 Solutions engineering to Sopemea Technologies 2 Inventory Locator Service to L3Harris Hamble aerostructure Solutions business to TRC Military Vehicles eAircraft 2 GDI Simulation to MBDA Alestis Aerospace stake [76%] NEXEYA CAMP Systems International Night Vision Apollo and Athene to Elbit Systems Stormscope product BAE Systems UK to Belcan Collins Psibernetix ElectroMechanical Websense to Aciturri Aeronautica RBSL JV w/ business to Aernnova Medav Technologies NVH stake [19.5%] 0 RUAG Switzerland Next Generation 911 to line to TransDigm