Sharing Success—Owning Failure Takes You a Step Closer to Successfully Meeting That Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Literacy’, ‘Fosters Inclusion’ Foundational Competencies Now in Myvector Self-Assessment Tool

THE SOUND OF FREEDOM | Wednesday, March 10, 2021 | 5 USAFE completes CJADC2 demonstration BY SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE PUBLIC AFFAIRS RAMSTEIN AIR BASE, Germany (AFNS) -- U.S. Air Forces in Europe-Air Forces Africa, in conjunction with the Department of the Air Force’s Chief Ar- chitect’s O ce, conducted a Combined, Joint All-Domain Command and Control demonstration in international waters and airspace in and around the Baltic Sea. Participation included assets from U.S. Naval Forces Europe – Africa/U.S. 6th Fleet, U.S. Army Europe – Africa, U.S. Strategic Command, the Royal Air Force, the Royal Netherlands air force and the Polish air force. This demonstration was designed to test and observe the ability of the joint force, our allies and partners to integrate and provide command and control across multiple networks to multiple force capa- bilities. “Conducting a complex and real-world U.S. AIR FORCE PHOTO BY TECH. SGT. EMERSON NUÑEZ focused CJADC2 demonstration allowed A U.S. Air Force F-16 Fighting Falcon assigned to the 555th Fighter Squadron, Aviano Air Base, Italy, is refueled by a KC-135 our joint and allied team to nd areas Stratotanker assigned to the 100th Air Refueling Wing, RAF Mildenhall, United Kingdom, during a mission over the Black Sea, where we can innovate with systems we Jan. 14, 2021. U.S. military operations in the Black Sea enhance regional stability, combined readiness and capability with our already have and also to identify areas NATO allies and partners. where our war ghters need assistance from the Air and Space Forces’ Chief Ar- ported the demonstration. -

The War Years

1941 - 1945 George Northsea: The War Years by Steven Northsea April 28, 2015 George Northsea - The War Years 1941-42 George is listed in the 1941 East High Yearbook as Class of 1941 and his picture and the "senior" comments about him are below: We do know that he was living with his parents at 1223 15th Ave in Rockford, Illinois in 1941. The Rockford, Illinois city directory for 1941 lists him there and his occupation as a laborer. The Rockford City Directory of 1942 lists George at the same address and his occupation is now "Electrician." George says in a journal written in 1990, "I completed high school in January of 1942 (actually 1941), but graduation ceremony wasn't until June. In the meantime I went to Los Angeles, California. I tried a couple of times getting a job as I was only 17 years old. I finally went to work for Van De Camp restaurant and drive-in as a bus boy. 6 days a week, $20.00 a week and two meals a day. The waitresses pitched in each week from their tips for the bus boys. That was another 3 or 4 dollars a week. I was fortunate to find a garage apartment a few blocks from work - $3 a week. I spent about $1.00 on laundry and $2.00 on cigarettes. I saved money." (italics mine) "The first part of May, I quit my job to go back to Rockford (Illinois) for graduation. I hitch hiked 2000 miles in 4 days. I arrived at my family's house at 4:00 AM one morning. -

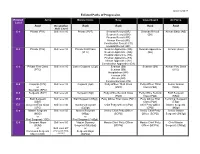

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Table of Contents

June 30, 2006 TTable of TTcontents Independence Day Air Force, U.S. CENTAF leaders offer messages for July 4: Page 2 “Teamwork” Capt. Dietrich speaks on working together to accomplish great things: Page 4 Commander’s Call Col. Orr highlights ‘fantastic job’ group has done through 30 days: Pages 5-6 Big Crane ECES helps move barriers for new Muscle Beach expansion: Page 6 Keeping track of it LRS supply team manages, issues mission items: Pages 7-8 Remembering Khobar Military commemorates 10th anni- versary of Khobar Tower bombing: Page 9 Around Iraq Latest news from around the the- ater: Page 9 Keeping cool Joint ECES effort generates, deliv- ers electricity: Page 10 Chapel corner Chaplain offers thoughts on religion versus relationship: Page 11 Looking for losers Muscle Beach looking for people willing to lose weight: Page 12 Blind volleyball PERSCO overwhelms ECS to take championship: Page 13 Movies and more Event schedules: Pages 14-16 Ali Times / June 30, 2006 Page 2 Air Force leaders send July 4 message Happy Birthday, America! For 230 years, this nation and its peo- ple have represented freedom and democracy. We earned that repu- Vol. 4, Issue 26 tation through courageous acts of June 30, 2006 patriotism by our founding fathers Col. and through bravery on battle- David L. Orr fields across the world. Today we Commander, 407th AEG mark not a resounding victory in Lt. Col. a great battle, but instead the day Richard H. Converse when we stood up as a free and Deputy Commander, Air Force Secretary Air Force Chief of Staff independent nation and told the 407th AEG Michael W. -

Der Krieg Gegen Die Bundesrepublik Jugoslawien 1999

Der Krieg gegen die Bundesrepublik Jugoslawien - 24. März bis 10./20. Juni 1999 Inhalt 1. Zum Luftkrieg Verteidiger, Angreifer und die Verluste 2. Zum Hintergrund des Krieges: Literaturtips und einige Beiträge 3. Zu allen Zeiten: Propaganda 4. Die "Helden" der US-Air-Force: 509th Bomb Wing 5. Dokumentierte Abschüsse: F-117-Abschuß durch MiG-21 und Fla-Rakete MiG-29-Abschuß durch F-15 Eagle 6. andere Berichte: Links 1. Zum Luftkrieg Die jugoslawische Luftverteidigung Die jugoslawischen Luftabwehr hatte vorwiegend verschiedene sowjetische Raketensysteme in ihrem Bestand. Die etwa 60 bis 68 selbstfahrenden Systeme SA-6 Kub sollen besonders wirksam gegen tief fliegende Kampfflugzeuge und Raketen in einer Reichweite von 100 bis 200 Kilometern sein. Hinzu kamen noch - in geringen Stückzahlen - bei der Luftverteidigung die SA-8b, SA-9 und SA- 13. Die stationären Systeme SA-2 und SA-3 schützten vor allem die großen Städte, Militäreinrichtungen sowie wichtige Industrieanlagen. Hiervon standen jeweils 60 Abschußvorrichtungen zur Verfügung. Die jugoslawischen Luftstreitkräfte waren in zwei Fliegerkorps, eine Aufklärungsstaffel sowie eine Lufttransportbrigade unterteilt. Die "westlichen" Schätzungen der Stückzahlen an Flugzeugen schwanken zwischen 225 und 252 Maschinen [Zahlendreher?]. Gesichert scheint, zu Beginn des Krieges, der Bestand an 16 MiG-29 (darunter 2 zweisitzige Schulmaschinen) und 60 MiG-21. Die 65 Maschinen der jugoslawisch - rumänischen Koproduktion Soko Orao und die etwa 80 Maschinen vom Typ Galeb G-4 und G-2 sowie Jastreb sind als Trainer und leichte Erdkampfflugzeuge ausgelegt und dürften für Luftverteidigungsaufgaben nur sehr bedingt tauglich gewesen sein. Hinzu kamen rd. 70 Hubschrauber (andere Angaben sprechen von 110 oder gar 180) vom Typ Partizan (ca. -

Air & Space Power Journal

July–August 2013 Volume 27, No. 4 AFRP 10-1 Senior Leader Perspective The Air Advisor ❙ 4 The Face of US Air Force Engagement Maj Gen Timothy M. Zadalis, USAF Features The Swarm, the Cloud, and the Importance of Getting There First ❙ 14 What’s at Stake in the Remote Aviation Culture Debate Maj David J. Blair, USAF Capt Nick Helms, USAF The Next Lightweight Fighter ❙ 39 Not Your Grandfather’s Combat Aircraft Col Michael W. Pietrucha, USAF Building Partnership Capacity by Using MQ-9s in the Asia-Pacific ❙ 59 Col Andrew A. Torelli, USAF Personnel Security during Joint Operations with Foreign Military Forces ❙ 79 David C. Aykens Departments 101 ❙ Views The Glass Ceiling for Remotely Piloted Aircraft ❙ 101 Lt Col Lawrence Spinetta, PhD, USAF Funding Cyberspace: The Case for an Air Force Venture Capital Initiative ❙ 119 Maj Chadwick M. Steipp, USAF Strategic Distraction: The Consequence of Neglecting Organizational Design ❙ 129 Col John F. Price Jr., USAF 140 ❙ Book Reviews Master of the Air: William Tunner and the Success of Military Airlift . 140 Robert A. Slayton Reviewer: Frank Kalesnik, PhD Selling Air Power: Military Aviation and American Popular Culture after World War II . 142 Steve Call Reviewer: Scott D. Murdock From Lexington to Baghdad and Beyond: War and Politics in the American Experience, 3rd ed . 144 Donald M. Snow and Dennis M. Drew Reviewer: Capt Chris Sanders, USAF Beer, Bacon, and Bullets: Culture in Coalition Warfare from Gallipoli to Iraq . 147 Gal Luft Reviewer: Col Chad T. Manske, USAF Global Air Power . 149 John Andreas Olsen, editor Reviewer: Lt Col P. -

Training Support Activity Europe a Year in Photos 2018 U.S

TRAINING SUPPORT ACTIVITY EUROPE A YEAR IN PHOTOS 2018 U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR) Seventh Army Training Training Support Activity Command (7thATC) Europe (TSAE) U.S. Army Europe is the operation- » Maintains the critical logistical, » Readiness is our #1 priority; » 7th Army Training Command, al-level Army force assigned to U.S. communications, intelligence, we deliver ready, trained, and Training Support Activity Europe European Command. medical and transportation equipped forces for operational (TSAE) provides home-station, infrastructure needed to support demands. expeditionary, rotational, and » Shapes the U.S. European operations and contingencies. contingency training support » Resource training readiness for Command area of operations across the EUCOM and AFRICOM » Serves as a logistical hub to all of USAREUR’s assigned and in order to support operations, Areas of Responsibility in order move equipment, supplies and allocated forces throughout the develop relationships, assure to build readiness and increase personnel, including vehicles and EUCOM area of operations. access, build partner capacity and interoperability of all U.S. equipment forward-positioned in deter adversaries while provid- » Lead the Army in developing assigned, attached, regionally Europe. ing mission command capability Allied and partnered nation aligned forces, our Multi-Na- that can set the theater and » Conducts more than 1,000 theater interoperability; provide the tional Partners, and Allies. execute Unified Land Operations security cooperation events each Army with an active learning, On behalf of USAREUR, TSAE in support of Combatant year, including more than 50 near peer environment to press manages the Training Support Commander requirements. scheduled multinational exercises modernization initiatives. System management process and dozens of unscheduled and the theater Visual Informa- » Provides a visible symbol of U.S. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Fall 2004

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen John P. Jumper Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Donald G. Cook http://www.af.mil Commander, Air University Lt Gen John F. Regni Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education Col Randal D. Fullhart Editor Lt Col Paul D. Berg http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Senior Editor Lt Col Malcolm D. Grimes Associate Editor Maj Donald R. Ferguson Editor and Military Defense Analyst Col Larry Carter, USAF, Retired Professional Staff Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor http://www.au.af.mil Philip S. Adkins, Contributing Editor Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager Air and Space Power Chronicles Luetwinder T. Eaves, Managing Editor http://www.cadre.maxwell.af.mil The Air and Space Power Journal, published quarterly, is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innova tive thinking on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of na tional defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanc tion of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or Visit Air and Space Power Journal online in part without permission. If they are reproduced, at http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. -

Each Cadet Squadron Is Sponsored by an Active Duty Unit. Below Is The

Each Cadet Squadron is sponsored by an Active Duty Unit. Below is the listing for the Cadet Squadron and the Sponsor Unit CS SPONSOR WING BASE MAJCOM 1 1st Fighter Wing 1 FW Langley AFB VA ACC 2 388th Fighter Wing 388 FW Hill AFB UT ACC 3 60th Air Mobility Wing 60 AMW Travis AFB CA AMC 4 15th Wing 15 WG Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam PACAF 5 12th Flying Training Wing 12 FTW Randolph AFB TX AETC 6 4th Fighter Wing 4 FW Seymour Johonson AFB NC ACC 7 49th Fighter Wing 49 FW Holloman AFB NM ACC 8 46th Test Wing 46 TW Eglin AFB FL AFMC 9 23rd Wing 23 WG Moody AFB GA ACC 10 56th Fighter Wing 56 FW Luke AFB AZ AETC 11 55th Wing AND 11th Wing 55WG AND 11WG Offutt AFB NE AND Andrews AFB ACC 12 325th Fighter Wing 325 FW Tyndall AFB FL AETC 13 92nd Air Refueling Wing 92 ARW Fairchild AFB WA AMC 14 412th Test Wing 412 TW Edwards AFB CA AFMC 15 355th Fighter Wing 375 AMW Scott AFB IL AMC 16 89th Airlift Wing 89 AW Andrews AFB MD AMC 17 437th Airlift Wing 437 AW Charleston AFB SC AMC 18 314th Airlift Wing 314 AW Little Rock AFB AR AETC 19 19th Airlift Wing 19 AW Little Rock AFB AR AMC 20 20th Fighter Wing 20 FW Shaw AFB SC ACC 21 366th Fighter Wing AND 439 AW 366 FW Mountain Home AFB ID AND Westover ARB ACC/AFRC 22 22nd Air Refueling Wing 22 ARW McConnell AFB KS AMC 23 305th Air Mobility Wing 305 AMW McGuire AFB NJ AMC 24 375th Air Mobility Wing 355 FW Davis-Monthan AFB AZ ACC 25 432nd Wing 432 WG Creech AFB ACC 26 57th Wing 57 WG Nellis AFB NV ACC 27 1st Special Operations Wing 1 SOW Hurlburt Field FL AFSOC 28 96th Air Base Wing AND 434th ARW 96 ABW -

Dear Mountain View Lodge Guest, Welcome to Aviano Air Base Italy

Mountain View Lodge Dear Mountain View Lodge Guest, Welcome to Aviano air Base Italy. Whether this is your new permanent change of sta- tion, temporary duty assignment or you are just visiting our beautiful base, we sincerely hope you find your new home away from home comfortable and enjoyable. Aviano and the surrounding area have much to offer during all four seasons. If you enjoy out- doorsy adventures, our Outdoor Recreation staff offer great Dolomite Mountain hiking trips or snow skiing packages. If traveling and experiencing different cultures is more your speed, check out Information Travel and Tickets office! They offer custom private tour packages to major European cities such as Milan, Venice, Florence, Innsbruck, London, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, and more. For the visiting foodie, we offer great food and entertainment at the La Belle Vista Club, Mulligans Grill at the Alpine Golf Course or you can try the Italian Mensa. The 31st Force Support Squadron has it all! We are proud and honored to have you as our guest! Rest assured the staff and man- agement of the Mountain View Lodge will strive to provide you with the best lodging amenities, furnishings and service possible. We promise to ensure you have a clean, comfortable and pleasant room to guarantee a good night’s rest. Please let us know immediately if there is anything that we can do to improve your stay by contacting the front desk at 632-4040 or 0 and they will direct your call to the appropriate person. At the end of your stay, please complete the emailed customer comment survey so that we can get some feedback on your stay! With constructive feedback we improve and grow so that your next visit will be perfect. -

NSIAD-96-82 Air Force Aircraft: Consolidating Fighter Squadrons

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Committees May 1996 AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT Consolidating Fighter Squadrons Could Reduce Costs GOA years 1921 - 1996 GAO/NSIAD-96-82 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-271047 May 6, 1996 The Honorable John R. Kasich Chairman, Committee on the Budget House of Representatives The Honorable Herbert H. Bateman Chairman The Honorable Norman Sisisky Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on Military Readiness Committee on National Security House of Representatives In 1992, the Air Force decided to reconfigure its fighter force into smaller squadrons. This decision occurred at a time when the Secretary of Defense was attempting to reduce defense operating and infrastructure costs. We evaluated the cost-effectiveness of the Air Force operating its fighter forces in smaller squadron sizes and the implications this might have on the Secretary of Defense’s efforts to reduce defense infrastructure costs. We focused on the C and D models of the Air Force’s active component F-15s and F-16s. Because of your interest in this subject, we are addressing this report to you. To achieve directed force structure reductions, the Air Force has been Background reducing the number of F-15 and F-16 aircraft in its inventory. Between fiscal years 1991 and 1997, the Air Force plans to reduce its F-15 aircraft from 342 to 252. Over this same period, the Air Force plans to reduce its F-16 aircraft from 570 to 444. In 1991, F-15 and F-16 aircraft were configured in 42 squadrons. -

Biography Colonel Nicholas J. Demarco

BIOGRAPHY COLONEL NICHOLAS J. DEMARCO Colonel Nicholas J. DeMarco is the Chief of Airman and Family Care Division, Directorate of Services, Headquarters United States Air Force. He provides policy, technical direction and oversight for the Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations, Air Force protocol, oversight for uniforms, awards and recognition, Airman and Family readiness, Air Force Resiliency, Sexual Assault Prevention and Response program and other commander-interest programs that contribute to military force sustainment. He assumed his duties in Sept 2012. Col DeMarco graduated from George J. Penney High School, East Hartford, Connecticut in 1975. He enlisted in the Air Force in 1980 and spent four years at Myrtle Beach AFB, S.C. as an Accounting and Finance technician. He was commissioned in 1986 through the Reserve Officer Training Corps at Charleston Southern University, spending his first seven years as a Special Agent in the Air Force Office of Special Investigations in Los Angeles AFB, CA and Aviano AFB, Italy. He cross-flowed into the Services career field in 1994 and held positions as a Flight Chief, Deputy Services Director and Chief of Plans and Readiness. His previous command experience was as the Commander of the Okuma Joint Services Recreation Facility, Okinawa, Japan, and as commander of the 89th Services Squadron, Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland. He has Joint experience as the CENTCOM Joint Mortuary Affairs Officer, and was a Deputy Mission Support Group Commander. His last assignment prior to coming to Headquarters Air Force was as the Chief of Services, HQ Pacific Air Forces. EDUCATION: 1986: Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration, Charleston Southern Univ, S.C.