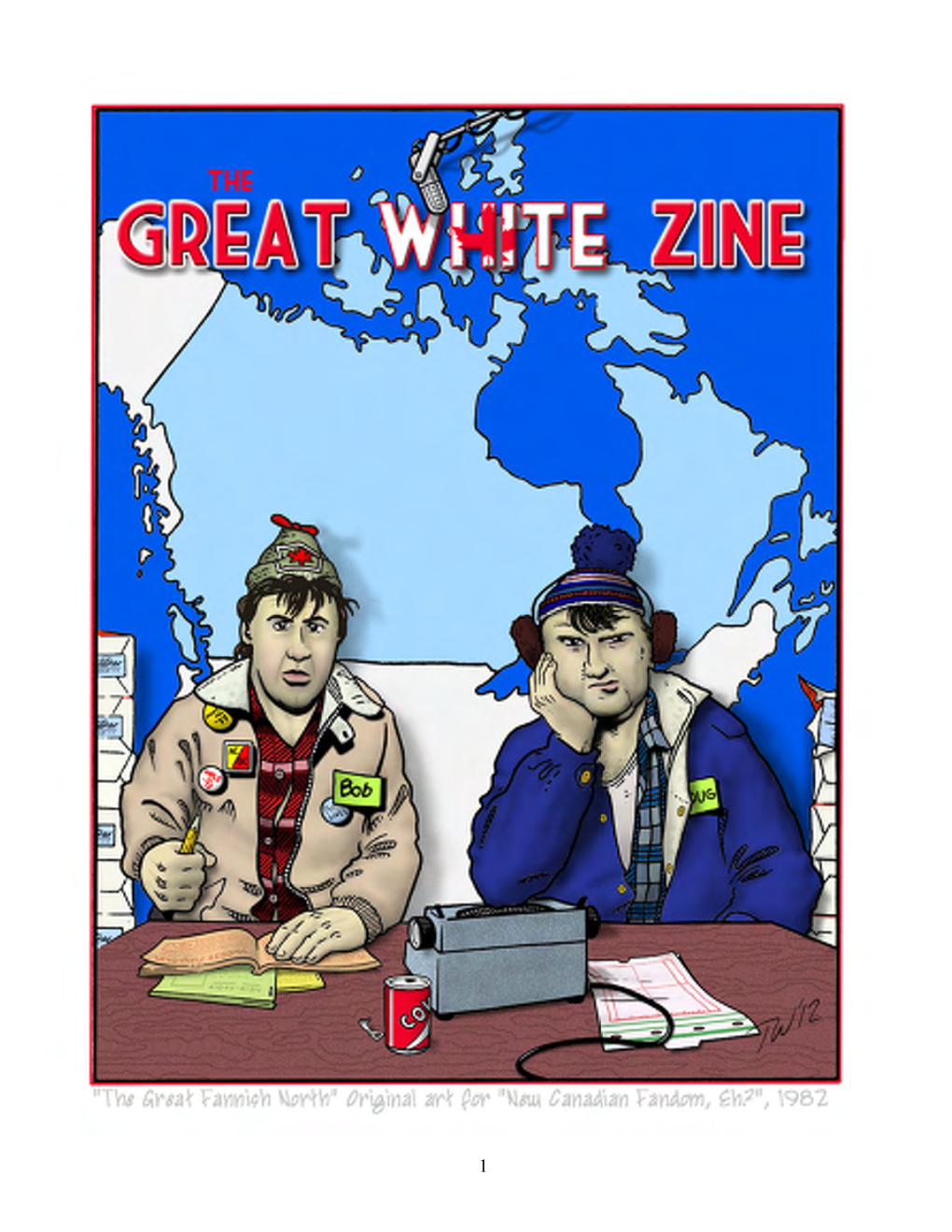

The Great White Zine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

The Brain That Changes Itself

The Brain That Changes Itself Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science NORMAN DOIDGE, M.D. For Eugene L. Goldberg, M.D., because you said you might like to read it Contents 1 A Woman Perpetually Falling . Rescued by the Man Who Discovered the Plasticity of Our Senses 2 Building Herself a Better Brain A Woman Labeled "Retarded" Discovers How to Heal Herself 3 Redesigning the Brain A Scientist Changes Brains to Sharpen Perception and Memory, Increase Speed of Thought, and Heal Learning Problems 4 Acquiring Tastes and Loves What Neuroplasticity Teaches Us About Sexual Attraction and Love 5 Midnight Resurrections Stroke Victims Learn to Move and Speak Again 6 Brain Lock Unlocked Using Plasticity to Stop Worries, OPsessions, Compulsions, and Bad Habits 7 Pain The Dark Side of Plasticity 8 Imagination How Thinking Makes It So 9 Turning Our Ghosts into Ancestors Psychoanalysis as a Neuroplastic Therapy 10 Rejuvenation The Discovery of the Neuronal Stem Cell and Lessons for Preserving Our Brains 11 More than the Sum of Her Parts A Woman Shows Us How Radically Plastic the Brain Can Be Appendix 1 The Culturally Modified Brain Appendix 2 Plasticity and the Idea of Progress Note to the Reader All the names of people who have undergone neuroplastic transformations are real, except in the few places indicated, and in the cases of children and their families. The Notes and References section at the end of the book includes comments on both the chapters and the appendices. Preface This book is about the revolutionary discovery that the human brain can change itself, as told through the stories of the scientists, doctors, and patients who have together brought about these astonishing transformations. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K. ConFrancisco Report........................................... 5 Le Guin & Brian Attebery, eds.; Chimera, Mary 1993 Hugo Awards W inners................................5 Rosenblum; Core, Paul Preuss; A Tupolev Too Nebula Awards Weekend 1994 ............................6 Far, Brian Aldiss; SHORT TAKES: Argyll: A The Preiss/Bester Connection.............................6 Memoir, Theodore Sturgeon; The Rediscovery THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Delany Back in P rint............................................ 6 of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of HWA Changes......................................................6 Cordwainer Smith, Cordwainer Smith. (ISSN-0047-4959) 1992 Chesley Awards W inners............................6 Reviews by Russell Letson:................................21 EDITOR & PUBLISHER Bidding War for Paramount.................................7 The Mind Pool, Charles Sheffield; More Than Charles N. Brown Battle of the Fantasy Encyclopedias................... 7 Fire, Philip Jose Farmer; The Sea’s Furthest ASSOCIATE EDITOR Fantasy Shop Helps AIDS F u n d ......................... 9 End, Damien Broderick. SPECIAL FEATURES Reviews by Faren M iller................................... 23 Faren C. Miller Complete Hugo Voting.......................................36 Green Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson; Brother ASSISTANT EDITORS 1993 Hugo Awards Ceremony........................... 38 Termite, Patricia Anthony; Lasher, Anne Rice; A Marianne -

File 770 #132

September 1999 1 2 File 770:132 The Last Diagnostician: I met James White at Intersection James White in 1995. We shared hot dogs in the SECC food court and talked 1928-1999 about what he might do as next year's Worldcon guest of honor. Tor Books was taking over publishing his Sector General series. They issued The Galactic Gourmet to coincide with We all look up to James here, and not just L.A.con III. Final Diagnosis and Mind Changer followed, and because he is about 6 1/2 feet tall. -- Walt Willis Double Contact is in the pipeline. All were edited by Teresa Nielsen Hayden, who did a wonderful interview of James James White died August 23 in Norn Iron, the day after during our Friday night GoH programming. suffering a stroke. His son, Martin, told Geri Sullivan that so far The committee fell completely under his charm. Gary Louie as he knew it was over very quickly. White was 71. spent countless hours compiling a “concordance” of terms and Looking around the obituaries and medical reports in this ideas from White’s science fiction (as yet unfinished). Fans issue makes me believe there must be an epidemic rampaging invented strange “alien food” to display and serve at a book among the nicest and sweetest people in fandom. And if charm, launch party in the Fan Lounge. Bruce Pelz issued t-shirts for a rich sense of humor and a gracious interest in everyone they “The White Company.” He also had about 15 “Diagnostician” met were the chief traits of the victims, none were more at risk badge ribbons printed, given to James to present to fans he than three Irish fans who made SLANT among the finest found especially helpful. -

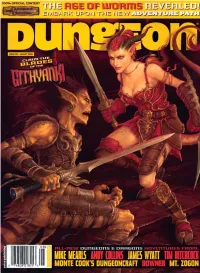

Dungeon Magazine #125.Pdf

#125 MAP & HANDOUT SUPPLEMENT PRODUCED BY PAIZO PUBLISHING, LLC. WWW.PAIZO.COM Joachim Barrum THE THREE FACES OF EVIL By Mike Mearls Clues discovered in Diamond Lake lead to the Dark Cathedral, a forlorn chamber hid- den below a local mine. There the PCs battle the machinations of the Ebon Triad, a cult dedicated to three vile gods. What does the Ebon Triad know about the Age of Worms, and why are they so desperate to get it started? An Age of Worms Adventure Path scenario for 3rd-level characters. Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 1 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Theldrick Ragnolin Eva Widermann Dourstone Eva Widermann Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 2 DUNGEON 125 Supplement The Faceless One Grallak Kur Eva Widermann Steve Prescott Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 3 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Steve Prescott Horshoe Area 17 Caverns 5 ft. Area 14 Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 4 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Caves of Erythnul 12 N KKKK 13 A G 18 A 14 17 15 16 One square = 5 feet Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Grimlock Cavern 19 up 18 20 down N 21 One square = 5 feet Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. -

Corflu 37 Program Book (March 2020)

“We’re Having a Heatwave”+ Lyrics adapted from the original by John Purcell* We’re having a heatwave, A trufannish heatwave! The faneds are pubbing, The mimeo’s humming – It’s Corflu Heatwave! We’re starting a heatwave, Not going to Con-Cave; From Croydon to Vegas To bloody hell Texas, It’s Corflu Heatwave! —— + scansion approximate (*with apologies to Irving Berlin) 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Corflu 37! The annual Science Fiction Fanzine Fans’ Convention. The local Texas weather forecast…………………………………….4 Program…………………………………………………………………………..5 Local Restaurant Map & Guide…………..……………………………8 Tributes to Steve Stiles:…………………………………………………..12 Ted White, Richard Lynch, Michael Dobson Auction Catalog……………………………………………………………...21 The Membership…………………………………………………………….38 The Responsible Parties………………………………………………....40 Writer, Editor, Publisher, and producer of what you are holding: John Purcell 3744 Marielene Circle, College Station, TX 77845 USA Cover & interior art by Teddy Harvia and Brad Foster except Steve Stiles: Contents © 2020 by John A. Purcell. All rights revert to contrib- uting writers and artists upon publication. 3 Your Local Texas Weather Forecast In short, it’s usually unpredictable, but usually by mid- March the Brazos Valley region of Texas averages in dai- ly highs of 70˚ F, and nightly lows between 45˚to 55˚F. With that in mind, here is what is forecast for the week that envelopes Corflu Heatwave: Wednesday, March 11th - 78˚/60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Thursday, March 12th - 75˚/ 61˚ F or 24˚/15˚ C Friday, March 13th - 77˚/ 58˚ F or 25 / 15˚ C - Saturday, March 14th - 76˚/ 58 ˚F or 24 / 15˚C Sunday, March 15th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Monday March 16th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C Tuesday, March 17th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C At present, no rain is in the forecast for that week. -

Dragon Magazine #120

Magazine Issue #120 Vol. XI, No. 11 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS April 1987 9 PLAYERS HANDBOOK II: Publisher The ENRAGED GLACIERS & GHOULS games first volume! Mike Cook Six bizarre articles by Alan Webster, Steven P. King, Rick Reid, Jonathan Edelstein, and Editor James MacDougall. Roger E. Moore 20 The 1987 ORIGINS AWARDS BALL0T: A special but quite serious chance to vote for the best! Just clip (or copy) and mail! Assistant editor Fiction editor Robin Jenkins Patrick L. Price OTHER FEATURES Editorial assistants 24 Scorpion Tales Arlan P. Walker Marilyn Favaro Barbara G. Young A few little facts that may scare characters to death. Eileen Lucas Georgia Moore 28 First Impressions are Deceiving David A. Bellis Art director The charlatan NPC a mountebank, a trickster, and a DMs best friend. Roger Raupp 33 Bazaar of the Bizarre Bill Birdsall Three rings of command for any brave enough to try them. Production Staff 36 The Ecology of the Gas Spore Ed Greenwood Kim Lindau Gloria Habriga It isnt a beholder, but it isnt cuddly, either. Subscriptions Advertising 38 Higher Aspirations Mark L. Palmer Pat Schulz Mary Parkinson More zero-level spells for aspiring druids. 42 Plane Speaking Jeff Grubb Creative editors Tuning in to the Outer Planes of existence. Ed Greenwood Jeff Grubb 46 Dragon Meat Robert Don Hughes Contributing artists What does one do with a dead dragon in the front yard? Linda Medley Timothy Truman 62 Operation: Zenith Merle M. Rasmussen David E. Martin Larry Elmore The undercover war on the High Frontier, for TOP SECRET® game fans. Jim Holloway Marvel Bullpen Brad Foster Bruce Simpson 64 Space-Age Espionage John Dunkelberg, Jr. -

|||FREE||| the Avengers: the Korvac Saga

THE AVENGERS: THE KORVAC SAGA FREE DOWNLOAD Jim Shooter | 196 pages | 31 Aug 2012 | Panini Publishing Ltd | 9781846531767 | English | Dartford, United Kingdom www.cbr.com Reading it now felt like a lot of work. In his human form, he looks skinny and weak and in his cosmic form, he glows with yellow cosmic energy with muscles and spiky hair. Refresh and try again. DK Publishing. Rows: Columns:. Cover by John Romita, Jr. Marvel Comics' Earth But inside the mansion a new foe is waiting Korvac gave The Avengers: The Korvac Saga and lets the Avengers beat him because the female model he hypnotized to be his wife was his true love Korvac happened to be attending a fashion show Universal Conquest Wiki. Origin of Michael aka Korvac. The writing and art invokes a sense of nostalgia. The power eventually reaches the year AD and inhabits Michael's father, Jordan, who is killed in battle with the Guardians. Jul 31, Stephen Snyder rated it it was amazing Shelves: graphic-novelsmarvel-comicsavengerscaptain- americairon-manthor-marvel-comics-character The Avengers: The Korvac Saga, new-york-nysuperheroesvisionquicksilver. The Korvac Saga! Avengers are vanishing one after another with no end in sight! Published May by Marvel. Notes: Korvac previously appeared in Thor Annual 6. When the Avengers and the Guardians arrived, he fought them, but even with their combined powers, Korvac easily defeated them in front of Corrina's eyes. This wiki. Avengers 1st Series I wish Nat had more lines in this one, but we Nat stans are sadly used to that by now and impatiently waiting for the much deserved solo movie. -

Hjino`M H\Ip\G•

Hjino`mH\ip\g. ROLEPLAYING GAME CORE RULES SampleMike Mearls • Greg Bilsland • Robert J. Schwalb file CREDITS Design Art Director Mike Mearls (lead), Greg Bilsland, Robert J. Schwalb Mari Kolkowsky Additional Design Graphic Designer Logan Bonner, Matt Goetz, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Bob Jordan Clifton Laird, Peter Lee, Stephen Radney-MacFarland, Matthew Sernett, Steve Townshend Cover Illustration Jesper Ejsing Development Rodney Thompson (lead), Interior Illustrations Stephen Radney-MacFarland, Peter Schaefer Rob Alexander, Dave Allsop, Thomas M. Baxa, Chippy, Brian Despain, Matt Dixon, Vincent Dutrait, Additional Development Steve Ellis, Wayne England, Jason A. Engle, Jason Felix, Greg Bilsland, Logan Bonner, Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Adam Gillespie, Tomás Giorello, E.M. Gist, Jeremy Crawford, Stephen Schubert, Chris Sims Woodrow Hinton III, Ralph Horsley, Howard Lyon, Jim Nelson, Wayne Reynolds, Chris Seaman, John Stanko, Editing Arnie Swekel, Matias Tapia, Franz Vohwinkel, Greg Bilsland (lead), Dawn J. Geluso, Eva Widermann, Ben Wootten Scott Fitzgerald Gray, Miranda Horner D&D Brand Team Additional Editing Liz Schuh, Jesse Decker, Kierin Chase, Laura Tommervik, Michele Carter, Andy Collins, Torah Cottrill Hilary Ross, Shelly Mazzanoble, Chris Lindsay Managing Editing Publishing Production Specialist Kim Mohan Erin Dorries Director of D&D R&D and Book Publishing Prepress Manager Bill Slavicsek Jefferson Dunlap D&D Creative Manager Imaging Technician Christopher Perkins Sven Bolen D&D Design Manager Production Manager James Wyatt Cynda Callaway D&D Development and Editing Manager Game rules based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® rules Andy Collins created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and the later editions by David “Zeb” Cook (2nd Edition); Jonathan Tweet, D&D Senior Art Director Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Jon Schindehette Peter Adkison (3rd Edition); and Rob Heinsoo, Andy Collins, and James Wyatt (4th Edition). -

|||GET||| Marvels Guardians of the Galaxy 1St Edition

MARVELS GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE none | 9780316271707 | | | | | Collecting Guardians of the Galaxy comic books as graphic novels Marvel Comics Presents Not collected. Drax appears. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3 15 July Collected in Guardians Disassembled, below. A new ongoing series starring the original Guardians, titled Guardians and written by Abnett, launched in Multiversity Comics. Avengers: Celestial Quest 8 Warlock in 8. Collected with Thanos imperactive, above, and in Realm of Kings Omnibus, above. Hidden categories: CS1 maint: extra text: authors list Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Groups Marvels Guardians of the Galaxy 1st edition Moved from supergroup. Marvel Spotlight Drax appears. Despite any minor qualms I had, I really did enjoy working on the series. The original members of the team include Major Vance Astro later known as Major Victoryan astronaut from 20th century Earth who spends a thousand years travelling to Alpha Centauri in suspended animation. After teaming with the thunder god Thor to defeat Korvac in the 31st century, [7] the guardians then Marvels Guardians of the Galaxy 1st edition Korvac to 20th century mainstream Earth, where together with the Avengers they fight a final battle. Gamora appears in 1. In issues 7 and 16 of the series, it was revealed a great "error" in the present day has caused the future to be destroyed; Starhawk is constantly trying to prevent it by time travel, causing the future and the Guardians to be altered. See Fantastic Four. Likely collected with the Rocket Raccoon series, below.