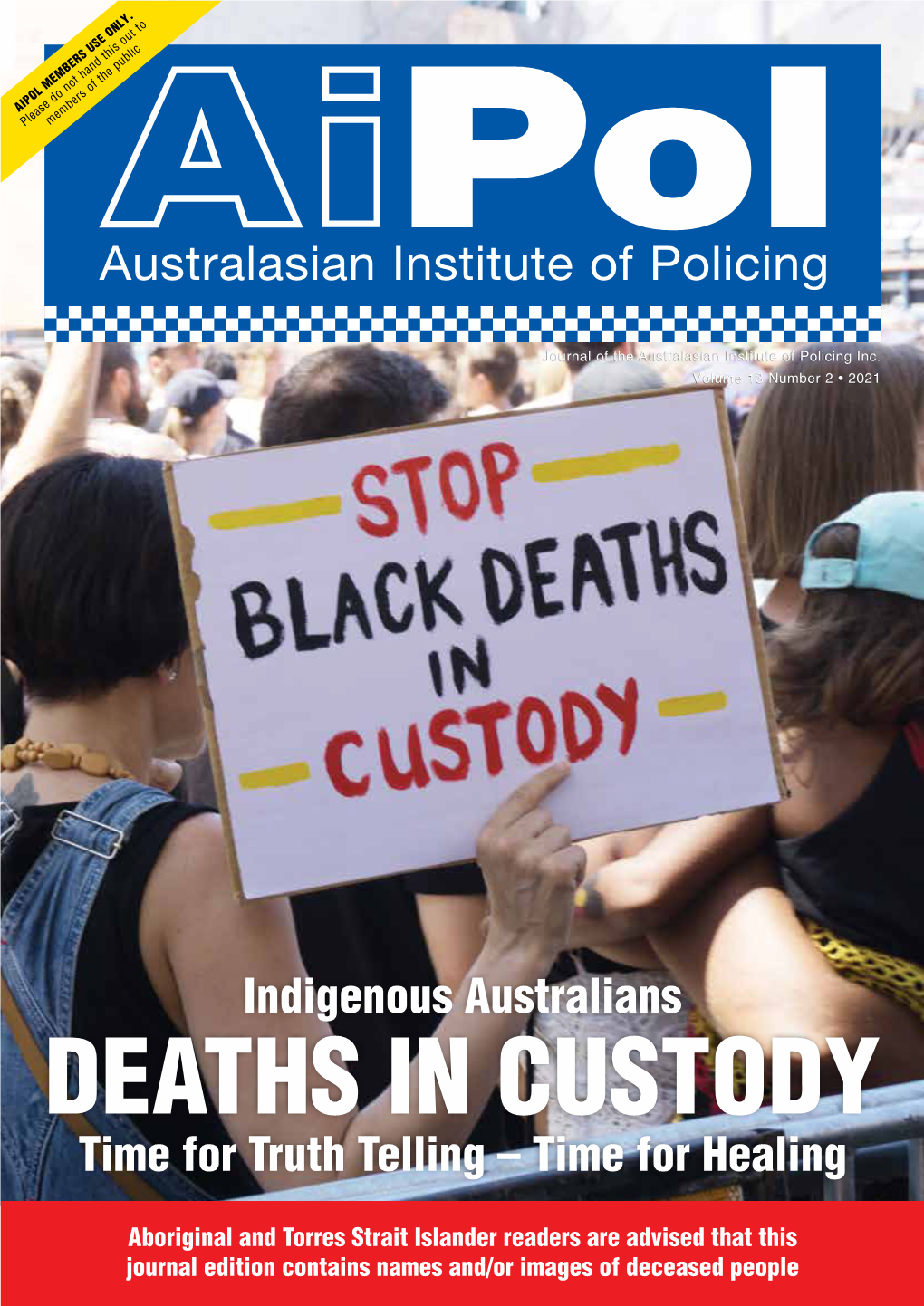

DEATHS in CUSTODY Time for Truth Telling – Time for Healing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights Law Centre Ltd Level 17, 461 Bourke Street Melbourne VIC 3000

Shahleena Musk and Adrianne Walters Human Rights Law Centre Ltd Level 17, 461 Bourke Street Melbourne VIC 3000 T: + 61 3 8636 4400 F: + 61 3 8636 4455 E: [email protected]/[email protected] W: www.hrlc.org.au The Human Rights Law Centre uses a strategic combination of legal action, advocacy, research, education and UN engagement to protect and promote human rights in Australia and in Australian activities overseas. It is an independent and not-for-profit organisation and donations are tax-deductible. Follow us at http://twitter.com/rightsagenda Join us at www.facebook.com/HumanRightsLawCentreHRLC/ | 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1.1 Summary of submission 1 1.2 About this submission 2 1.3 Recommendations 2 2. RESPONSE TO QUESTIONS AND PROPOSALS 5 2.1 Bail and the remand population 5 2.2 Sentencing and Aboriginality 7 2.3 Sentencing options 9 2.4 Prison Programs, Parole and Unsupervised Release 11 2.5 Fines and drivers licences 14 2.6 Justice procedure offences – breach of community-based sentences 16 2.7 Alcohol 17 2.8 Female offenders 19 2.9 Aboriginal justice agreements and justice targets 20 2.10 Access to justice issues 21 2.11 Police accountability 23 2.12 Justice reinvestment 25 3. ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER CHILDREN 26 | 1. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should have access to the same rights as non- Indigenous people and should be able to expect fair treatment in the criminal justice system. Unfortunately, and despite many other inquiries and recommendations over the years, this is too often not the case across Australia’s criminal justice systems. -

Department of Justice Annual Report 2017-2018

Annual Report 2017/18 Statement of Compliance Mail: GPO Box F317 PERTH WA 6841 Phone: 9264 1600 Web: www.justice.wa.gov.au ISSN: 1837-0500 (Print) ISSN: 1838-4277 (Online) Hon John Quigley MLA Hon Francis Logan MLA Attorney General Minister for Corrective Services In accordance with Section 61 of the Financial Management Act 2006, I hereby submit for your information and presentation to Parliament, the Annual Report of the Department of Justice for the financial year ended 30 June 2018. This Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Financial Management Act 2006. Dr Adam Tomison Director General Department of Justice 19 September 2018 The Department of Justice chose this artwork “Seven Sisters Standing In a Line” to be the front cover of its inaugural Reconciliation Action Plan. Painted by a prisoner from Boronia Pre-Release Centre for Women, it also represents this year’s NAIDOC Week theme – “Because of Her, We Can.” This is how the artist describes the painting: “When I was a girl I slept out under the stars and that’s when I learned about a group of stars called the seven sisters. The seven sisters is one of my favourite stories. The seven sisters are women that are attacked many times on their way across country. But they fight back and escape to the night sky to become stars. The women of the story are strong and free and make me think of how strong Aboriginal women are.” Department of Justice // Annual Report 2017/18 2 Contents Overview of the Agency .................................................................................................. -

Dirty Talk : a Critical Discourse Analysis of Offensive Language Crimes

DIRTY TALK: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE CRIMES Elyse Methven A thesis submitted to the University of Technology Sydney in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law March 2017 Faculty of Law University of Technology Sydney CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree, nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elyse Methven Signature of Student: Date: 02 March 2017 ETHICS APPROVAL Ethics approval for this research was granted by the University of Technology Sydney (HREC UTS 2011–498A). ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the dedication and ongoing support of my doctoral thesis supervisors: Professor Katherine Biber, Associate Professor Penny Crofts and Associate Professor Thalia Anthony at the Faculty of Law, University of Technology Sydney (‘UTS’). I cannot overstate the benefit that I have derived from their constant generosity and mentorship. Thanks are due to Professor Alastair Pennycook, who provided invaluable feedback on the linguistic component of my research, and allowed me to audit his subject, co-taught with Emeritus Professor Theo van Leeuwen, ‘Language and Power’. Whilst undertaking this thesis, I was privileged to be a Quentin Bryce Law Doctoral Scholar and Teaching Fellow at UTS Faculty of Law. -

Social Justice and Native Title Report 2016

Social Justice and Native Title Report 2016 ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER SOCIAL JUSTICE COMMISSIONER The Australian Human Rights Commission encourages the dissemination and exchange of information provided in this publication. All material presented in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia, with the exception of: • The Australian Human Rights Commission Logo • Photographs and images • Any content or material provided by third parties The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Attribution Material obtained from this publication is to be attributed to the Commission with the following copyright notice: © Australian Human Rights Commission 2016. Social Justice and Native Title Report 2016 ISSN: 2204-1125 (Print version) Acknowledgements The Social Justice and Native Title Report 2016 was drafted by Akhil Abraham, Allyson Campbell, Amber Roberts, Carly Patman, Darren Dick, Helen Potts, Julia Smith, Kirsten Gray, Paul Wright and Robynne Quiggin. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner thanks the following staff of the Australian Human Rights Commission: Isaiah Dawe, Michelle Lindley, John Howell, Leon Wild, Emily Collett and the Investigation and Conciliation Section. Special thanks to the following Aboriginal communities and organisations who feature in this report: the Quandamooka people for allowing us to host the Indigenous Property Rights Banking Forum at Minjerribah, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) for hosting our Indigenous Property Rights Network meeting, Yothu Yindi Foundation CEO, Denise Bowden and Sean Bowden for facilitating permission for use of the photo of Mr Pupuli and the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia for facilitating permission for use of the photo of Mrs Roe. -

CHAPTER 5 Criminalisation and Policing in Indigenous Communities Chris Cunneen

CHAPTER 5 Criminalisation and Policing in Indigenous Communities Chris Cunneen Introduction The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Policing and minor offences The use of arrest for minor offences Problems with meeting bail conditions From over-policing to zero tolerance policing Police use of excessive force Deaths in custody Cultural and communicative differences Police interviews and the Anunga Rules Indigenous policing and social control Aboriginal community justice Indigenous Criminal Justice Policy Development Conclusion Introduction There are two broad purposes to this chapter. The first is to build on the analysis provided in the previous chapter and to consider in more depth the processes of criminalisation of Indigenous people in Australia through policing and the criminal law. The second purpose is to reflect on contemporary Indigenous modes of policing and governance. State policing in Indigenous communities is an important issue on any range of measures. For example, members of the Indigenous community of Palm Island were so impassioned after a death in police custody, they destroyed the local police station and courthouse. This should give us pause to reflect on community attitudes to criminalisation and the volatility of Aboriginal/police relations. In Western Australia Aboriginal people are 12 times more likely to be arrested than non-Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal women the over-representation in arrests compared to non-Aboriginal women is 47 times more likely (Blagg 2016: 75). Conversely, Indigenous victimisation rates are also high. The Steering Committee for the Report of Government Service Provision (SCROGSP) noted that, nationally, between 2010-2014 the rate of homicides for Indigenous people was 6.4 times the rate found among non-Indigenous people (SCROGSP 2016: 4.103). -

ABORIGINAL LEGAL SERVICE of WA Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2016

ABORIGINAL LEGAL SERVICE OF WA Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 RCIADIC 25 YEARS ON 2 1 0 9 1 9 6 1 RCIADIC (Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths In Custody) CONTENTS President Report Michael Blurton . 4 Chief Executive Officer Report Dennis Eggington . 5 ALSWA Executive Committee . 9 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, 25 Years On . 11 Director Legal Services Peter Collins . 13 Community Legal Education/Media Jodi Hoffmann . 24 Dennis Eggington, 20 Years as ALSWA CEO . 28 Chief Financial Officer John Poroch . 30 Financial Reports . 33 Additional Information . 55 CULTURAL WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this Annual Report contains images and names of people who have passed away. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 1 Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Offices PERTH (Head Office) GERALDTON 73 Forrest Street Piccadilly Suites West, Geraldton 6530 7 Aberdeen Street Perth WA 6000 Phone: 08 9921 4938 Toll Free: 1800 016 786 PO Box 8194, Perth Business Centre, Fax: 08 9921 1549 WA 6849 Phone: 08 9265 6666 HALLS CREEK Toll Free: Office 7 Halls Creek Community Resource Centre 1800 019 900 Thomas Street, Halls Creek 6770 Fax: 08 9221 1767 PO Box 162, Halls Creek 6770 Phone: 08 9168 6156 Fax: 08 9168 5328 ALBANY 51 Albany Highway KALGOORLIE Albany 6330 1/58 Egan Street Kalgoorlie PO Box 1016, Albany WA 6330 PO Box 1077, Kalgoorlie 6430 Phone: 08 9841 7833 Phone: 08 9021 3666 Toll Free: 1800 016 715 08 9021 3816 Fax: 08 9842 1651 Toll Free: 1800 016 791 Fax: 08 9021 6778 BROOME 1/41 Carnarvon Street Broome -

The Sydney Law Review Vol40 Num4

volume 40 number 4 december 2018 the sydney law review articles Non-State Policing, Legal Pluralism and the Mundane Governance of “Crime” – Amanda Porter 445 The Liability of Australian Online Intermediaries – Kylie Pappalardo and Nicolas Suzor 469 Adolescent Family Violence: What is the Role for Legal Responses? – Heather Douglas and Tamara Walsh 499 Contracts against Public Policy: Contracts for Meretricious Sexual Services – Angus Macauley 527 before the high court Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt: Evaluating Statutory Unconscionability in the Cultural Context of an Indigenous Community – Sharmin Tania and Rachel Yates 557 corrigendum 571 EDITORIAL BOARD Elisa Arcioni (Editor) Celeste Black (Editor) Tanya Mitchell Emily Crawford Joellen Riley John Eldridge Wojciech Sadurski Emily Hammond Michael Sevel Sheelagh McCracken Cameron Stewart STUDENT EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Angus Brown Tim Morgan Courtney Raad Book Review Editor: John Eldridge Before the High Court Editor: Emily Hammond Publishing Manager: Cate Stewart Correspondence should be addressed to: Sydney Law Review Law Publishing Unit Sydney Law School Building F10, Eastern Avenue UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Website and submissions: <https://sydney.edu.au/law/our-research/ publications/sydney-law-review.html> For subscriptions outside North America: <http://sydney.edu.au/sup/> For subscriptions in North America, contact Gaunt: [email protected] The Sydney Law Review is a refereed journal. © 2018 Sydney Law Review and authors. ISSN 0082–0512 (PRINT) ISSN 1444–9528 (ONLINE) Non-State Policing, Legal Pluralism and the Mundane Governance of “Crime” Amanda Porter Abstract Faced with the problem of rising incarceration rates, there has been an emerging discourse in recent years about the need to decolonise justice for Indigenous Australians. -

Institutional Racism, the Importance of Section 18C and the Tragic Death of Miss Dhu

INSTITUTIONAL RACISM, THE IMPORTANCE OF SECTION 18C AND THE TRAGIC DEATH OF MISS DHU by Alice Barter & Dennis Eggington INTRODUCTION part of the pastoral industry in north Western Australia. At the The contemporary incarceration of Australia’s First Peoples must turn of the century Aboriginal people were also imprisoned for be viewed in its historical and political context. This country is entering certain town sites, consuming alcohol, speaking their founded on a hierarchy of power which encourages white men language, and in the case of Aboriginal women, cohabiting with into positions of dominance and subjugates Aboriginal people, non-Aboriginal men.4 There was also extra-curial or vigilante especially Aboriginal women. In 2014, 22-year-old Yamatji woman, punishment and imprisonment. Across the country, Australia’s Miss Dhu, died while in police custody. She was a victim of First Peoples were captured and imprisoned by colonists and shot institutional racism. Currently there are calls to amend the Racial if they tried to escape for crimes such as ‘assertiveness’.5 There Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (‘the RDA’) to reduce the protections was also extreme frontier violence as part of the invasion of the afforded to minority groups, including Australia’s First Peoples. country; ‘for the facts are easily enough established that homicide, Section 18C provides an important reproach to overt racism and rape, and cruelty [towards First Nations people] have been an opportunity for community members to combat discrimination, commonplace over wide areas and long periods.’6 There have long including institutionalised racism. This paper highlights the been reports of Aboriginal women experiencing sexual and other intersectionality of institutional racism and gender discrimination violence by white men, especially those in positions of power. -

Managing Director Report December 2016

The recent death of a 10 year old Aboriginal child by suicide in a remote part of Managing Directors Report the Kimberley made everyone stand up and take notice of the issues December 2016 facing Aboriginal people in Australia today. That a child should choose death instead of remain life is not a circumstance that should ever be valid and a reality for any parent and as a community urges the current crop of lawmakers to read it. we cried tears of pain for this family. Having spent a considerable amount of the past Since this time we have had the WA Parliamentary 20 years working at the pointy end of suicide Inquiry into Suicides in Aboriginal Communities prevention and intervention, this issue is of particular (2015); a Suicide Prevention Round-table in the passion to me and it is fair to say that I have gone Kimberley with the Federal Minister for Health, to my fair share of funerals for many of my relations Sussan Ley; and we also now have a petition and community who have taken their own lives. on change.org for a Royal Commission into the issue. This has followed what appears to Quite simply I am frustrated that this issue has be an endless stream of government policies, been approached in a piecemeal and reactive frameworks and most soberingly a Coronial manner which has failed our communities. Enquiry into a spate of 21 Suicides in the Kimberley in 2011 and a further Coronial Enquiry My own personal journey in suicide prevention announced in May 2016. -

Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Limited

Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Limited Submission to the Australian Law Reform Commission's Discussion Paper on Incarceration Rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 11 September 2017 l ABOUT THE ABORIGINAL LEGAL SERVICE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA .................................................... ..4 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................... ..4 Scope of the reference ...................................................................................................................... ..4 Overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Western Australia ............ ..4 ALSWA SUBMISSION ............................................................................................................................. ..5 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................5 Contributing factors ....................................................................................................................5 Child protection and adult incarceration ....................................................................................7 Rural and remote ........................................................................................................................7 Bail and the Remand Population .........................................................................................................7 -

Sonic Archives of Breathlessness

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 5686–5704 1932–8036/20200005 Sonic Archives of Breathlessness POPPY DE SOUZA1 Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia This article conducts a close listening of the Australian podcast series Breathless: The Death of David Dungay Jr., which reports on the death in custody of Aboriginal man David Dungay and his family’s struggle for justice in its wake. Bringing an orientation toward sound and listening into conversation with Christina Sharpe’s concept of “archives of breathlessness,” it argues that Breathless can be heard as part of a larger sonic archive where Black and Indigenous breath is taken, stopped, let go, and held on to, and where the sounds of settler-colonial violence—and resistance to that violence—repeat across time and space. Drawing on notions of repetition, protraction, reckoning and recuperation, I explore the multiple ways “just hearings” in relation to Indigenous struggles for justice in the wake of colonization are stalled, protracted, and refused, while also listening for the sounds of Indigenous resistance, survival and moments of collective breath. Keywords: listening, sound, sonic archives, Indigenous deaths in custody, community media, podcasting I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. Poppy de Souza: [email protected] Date submitted: 2020-05-17 1 Thank you to generous feedback from Emma Russell, and for suggesting the title. -

Canada–Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Racism Working Group

Canada–Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Racism Working Group Discussion Paper and Literature Review Prepared for the Canada-Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Working Group by Associate Professor Chelsea Bond, Dr David Singh & Helena Kajlich Canada–Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Racism Working Group Discussion Paper and Literature Review Prepared for the Canada-Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Working Group by Associate Professor Chelsea Bond, Dr David Singh & Helena Kajlich © Copyright The Lowitja Institute, 2019 ISBN: 978-1-921889-62-2 First published August 2019 This work is published and disseminated as part of the activities of the Lowitja Institute, Australia’s national institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, or by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community organisations subject to an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial use or sale. Reproduction for other purposes or by other organisations requires the written permission of the copyright holder. Both a PDF version and printed copies of this review can be obtained from: The Lowitja Institute PO Box 650, Carlton South Victoria 3053 AUSTRALIA T: +61 3 8341 5555 F: +61 3 8341 5599 E: [email protected] W: www.lowitja.org.au Authors: Associate Professor Chelsea Bond, Dr David Singh & Helena Kajlich Editor: Cathy Edmonds Design: Dreamtime based on Inprint Design artwork Suggested citation: Bond, C., Singh, D. & Kajlich, H. 2019, Canada–Australia Indigenous Health and Wellness Racism Working Group Discussion Paper and Literature Review, Discussion Paper Series, The Lowitja Institute, Melbourne.