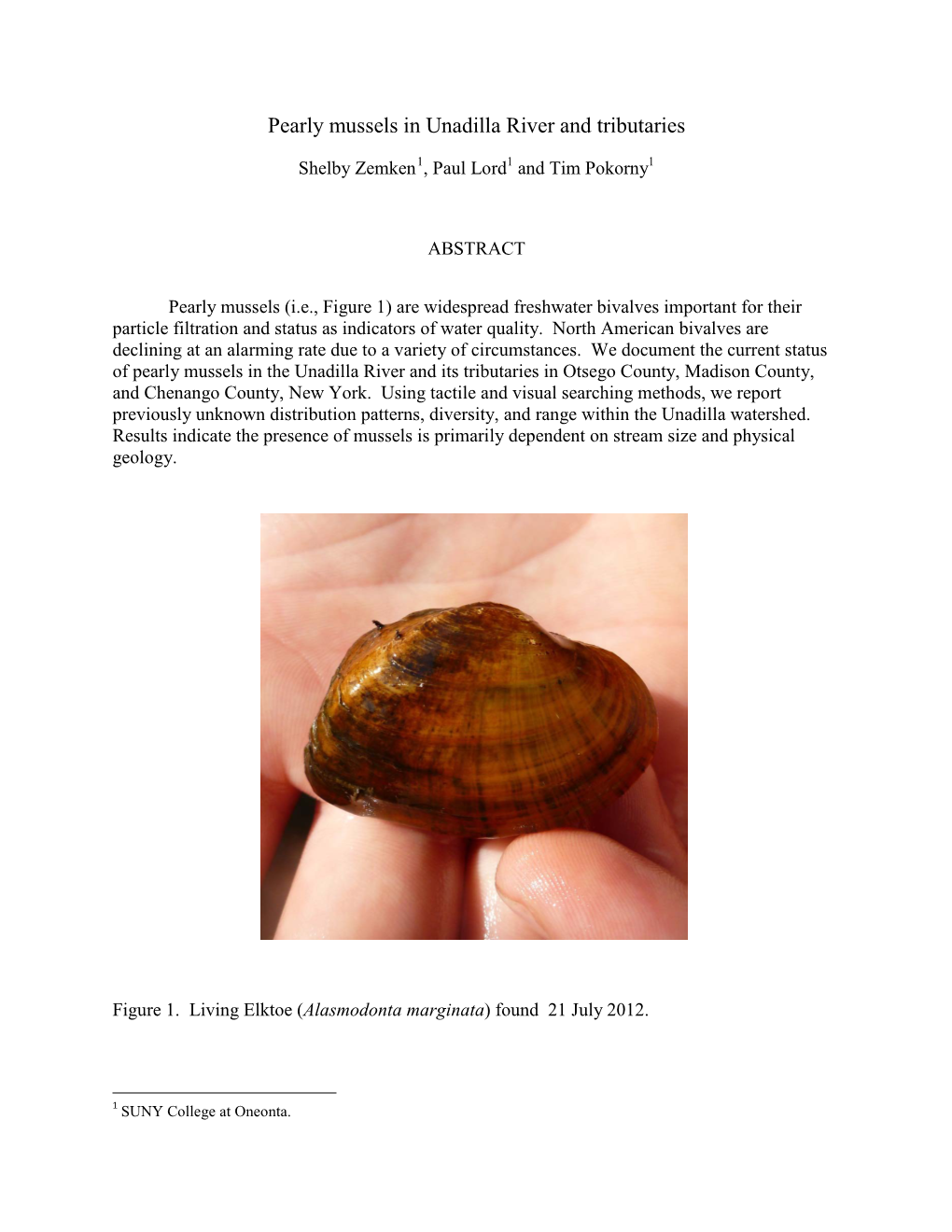

Pearly Mussels in Unadilla River and Tributaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 66, No. 27/Thursday, February 8, 2001/Proposed Rules

9540 Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 27 / Thursday, February 8, 2001 / Proposed Rules impose a minimal burden on small regulatory effect of the critical habitat white to bluish-white, changing to a entities. designation does not extend beyond salmon, pinkish, or brownish color in those activities funded, permitted, or the central and beak cavity portions of E. Federal Rules That May Duplicate, carried out by Federal agencies. State or the shell; some specimens may be Overlap, or Conflict With the Proposed private actions, with no Federal marked with irregular brownish Rules involvement, are not affected. blotches (adapted from Clarke 1981). 37. None. Section 4 of the Act requires us to Clarke (1981) contains a detailed consider the economic and other description of the species’ shell, with Ordering Clauses relevant impacts of specifying any illustrations; Ortmann (1921) discussed 38. Pursuant to Sections 1, 3, 4, 201– particular area as critical habitat. We soft parts. 205, 251 of the Communications Act of solicit data and comments from the Distribution, Habitat, and Life History 1934, as amended, 47 U.S.C. 151, 153, public on all aspects of this proposal, 154, 201–205, and 251, this Second including data on the economic and The Appalachian elktoe is known Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking other impacts of the designation. We only from the mountain streams of is hereby Adopted. may revise this proposal to incorporate western North Carolina and eastern 39. The Commission’s Consumer or address comments and other Tennessee. Although the complete Information Bureau, Reference information received during the historical range of the Appalachian Information Center, Shall Send a copy comment period. -

Pearly Mussels in NY State Susquehanna Watershed Paul H

Pearly mussels in NY State Susquehanna Watershed Paul H. Lord, Willard N. Harman & Timothy N. Pokorny Introduction Preliminary Results Discussion Pearly mussels (unionids) New unionid SGCN identified • Mobile substrates appear exacerbated endangered native mollusks in Susquehanna River Watershed by surge stormwater inputs • Life cycle complex • Eastern Pearlshell (Margaritifera margaritifera) - made worse by impervious surfaces - includes fish parasitism -- in Otselic River headwaters • Unionids impacted - involves watershed quality parameters Historical SGCN found in many locations by ↓O2, siltation, endocrine disrupting chemicals • 4 Species of Greatest Conservation Need • Regularly downstream of extended riffle - from human watershed use (SGCN) historically found • Require minimally mobile substrates • River location consistency with old maps in NY State Susquehanna Watershed • No observed wastewater treatment plant impact associated with ↑ unionids - Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) -adult unionids more easily observed - Green Floater (Lasmigona subviridis) Table 1. NYSDEC freshwater pearly mussel “species of greatest conservation need” (SGCN) observed in the Upper Susquehanna from kayaks - Yellow Lamp Mussel (Lampsilis cariosa) Watershed while mapping and searching rivers in the summers of 2008 Elktoe -Elktoe (Alasmidonta marginata) and 2009. Brook Floater = Alasmidonta varicosa; elktoe = Alasmidonta • Prior sampling done where convenient marginata; green floater = Lasmigona subviridis; yellow lamp mussel = - normally at intersection -

Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae)

1 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio and surrounding watersheds by Robert A. Krebs Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences Cleveland State University Cleveland, Ohio, USA 44115 September 2015 (Revised from 2009) 2 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio, and surrounding watersheds Acknowledgements I thank Dr. David Klarer for providing the stimulus for this project and Kristin Arend for a thorough review of the present revision. The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve provided housing and some equipment for local surveys while research support was provided by a Research Experiences for Undergraduates award from NSF (DBI 0243878) to B. Michael Walton, by an NOAA fellowship (NA07NOS4200018), and by an EFFRD award from Cleveland State University. Numerous students were instrumental in different aspects of the surveys: Mark Lyons, Trevor Prescott, Erin Steiner, Cal Borden, Louie Rundo, and John Hook. Specimens were collected under Ohio Scientific Collecting Permits 194 (2006), 141 (2007), and 11-101 (2008). The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), established by section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information on these preserves and programs is available from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office for Coastal Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U. S. Department of Commerce, 1305 East West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. -

Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan (Leptodea leptodon) February 2010 Department of the Interior United States Fish and Wildlife Service Great Lakes – Big Rivers Region (Region 3) Fort Snelling, MN Cover photo: Female scaleshell mussel (Leptodea leptodon), taken by Dr. M.C. Barnhart, Missouri State University Disclaimer This is the final scaleshell mussel (Leptodea leptodon) recovery plan. Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions believed required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after being signed by the Regional Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modifications as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. The plan will be revised as necessary, when more information on the species, its life history ecology, and management requirements are obtained. Literature citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan (Leptodea leptodon). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota. 118 pp. Recovery plans can be downloaded from the FWS website: http://endangered.fws.gov i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many individuals and organizations have contributed to our knowledge of the scaleshell mussel and work cooperatively to recover the species. -

Brook Floater

STATE THREATENED Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) photo by Ethan Nedeau Description The Brook Floater is a small to medium-sized (usually ≤ host to change into the subadult form of a mussel. Each 3 inches) freshwater mussel that in profile has a “Roman mussel species requires one or more specific fish species nose” shape and in cross-section is moderately inflated to serve as suitable hosts and since glochidia can only or swollen in appearance. The shell is yellowish-green in survive for a short time on their own, they must quickly young animals to brownish-black in older specimens, encounter just the right fish. The lucky ones attach to the and often has broad dark green rays. Internal hinge teeth fish’s gills or fins (without apparent harm to the fish) for are poorly developed, with only a small knob present on a period of weeks or months before transforming into each valve. A reliable diagnostic feature for this mussel tiny mussels and dropping off to settle in the substrate. is a series of ridges and wrinkles along the dorso- Fish species reported to serve as hosts for the Brook posterior slope of each valve, perpendicular to the Floater include Longnose Dace, Blacknose Dace, growth rings. This species has a peculiar habit of gaping Golden Shiner, Pumpkinseed Sunfish, Slimy Sculpin, its valves when removed from the water, exposing its and Yellow Perch. cantaloupe-colored “foot”. Freshwater mussels grow rapidly during their first 4-6 Range and Habitat years of life, before they become reproductively mature. The life span of the Brook Floater is likely 15 years or The Brook Floater is found in streams and rivers of the more. -

The Conservation Status of the Brook Floater Mussel, Alasmidonta

The conservation status of the brook floater mussel, Alasmidonta varicosa, in the Northeastern United States: trends in distribution, occurrence, and condition of populations Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (NEAFWA) Regional Conservation Needs Grant Program Topic 3. Identify NE species of greatest conservation need: data gaps, design data collection protocols, and collect data Barry J. Wicklow, Ph.D. Professor of Biology Saint Anselm College 100 Saint Anselm Drive Manchester, NH 03102-1310, Phone 603-641-7155, Fax 603-222-4012 [email protected] Susi von Oettingen, Endangered Species Biologist, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 70 Commercial Street, Concord, NH 03301 [email protected] Tina A. Cormier, Principal and Senior Spatial Analyst, Black Osprey Geospatial, Inc., 17 Shorecrest Drive, East Falmouth, MA 02536 [email protected] Julie Devers, Fishery Biologist U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Maryland Fishery Resources Office 177 Admiral Cochrane Drive, Annapolis, MD 21401 [email protected] Funds Requested from the NEAFWA RCN Program: 72,940 Duration: January 2013-December 2014 Project Description: Brook floaters have declined rapidly throughout their range due to habitat loss, stream fragmentation, loss of riparian vegetation buffers, upstream land degradation, pollution, altered flow regimes, extreme spring floods, and summer droughts. While the northeast holds the largest brook floater populations range wide, our long-term research shows populations once large and robust have either declined by 50 to 95% or are gone completely. We are apprehensive that most populations are facing the same fate, but trends are often undetected because of the lack of long-term monitoring. Although the brook floater was petitioned recently for listing under the Endangered Species Act, serious data gaps remain. -

Aquatic Biota

Low Gradient, Cool, Headwaters and Creeks Macrogroup: Headwaters and Creeks Shawsheen River, © John Phelan Ecologist or State Fish Game Agency for more information about this habitat. This map is based on a model and has had little field-checking. Contact your State Natural Heritage Description: Cool, slow-moving, headwaters and creeks of low-moderate elevation flat, marshy settings. These small streams of moderate to low elevations occur on flats or very gentle slopes in watersheds less than 39 sq.mi in size. The cool slow-moving waters may have high turbidity and be somewhat poorly oxygenated. Instream habitats are dominated by glide-pool and ripple-dune systems with runs interspersed by pools and a few short or no distinct riffles. Bed materials are predominenly sands, silt, and only isolated amounts of gravel. These low-gradient streams may have high sinuosity but are usually only slightly entrenched with adjacent Source: 1:100k NHD+ (USGS 2006), >= 1 sq.mi. drainage area floodplain and riparian wetland ecosystems. Cool water State Distribution:CT, ME, MD, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, VA, temperatures in these streams means the fish community WV contains a higher proportion of cool and warm water species relative to coldwater species. Additional variation in the stream Total Habitat (mi): 16,579 biological community is associated with acidic, calcareous, and neutral geologic settings where the pH of the water will limit the % Conserved: 11.5 Unit = Acres of 100m Riparian Buffer distribution of certain macroinvertebrates, plants, and other aquatic biota. The habitat can be further subdivided into 1) State State Miles of Acres Acres Total Acres headwaters that drain watersheds less than 4 sq.mi, and have an Habitat % Habitat GAP 1 - 2 GAP 3 Unsecured average bankfull width of 16 feet or 2) Creeks that include larger NY 41 6830 94 325 4726 streams with watersheds up to 39 sq.mi. -

Brook Floater

Brook Floater Alasmidonta varicosa Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife State Status: Endangered 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581 tel: (508) 389-6360; fax: (508) 389-7891 Federal Status: None www.nhesp.org Description: The brook floater is a small mussel that but the intensity of that color is variable. The brook floater rarely exceeds three inches (75mm) in length. The shape is has a unique habit of “gaping” (relaxing its adductor trapezoidal to almost elliptical, and it has a prominent muscles and opening its valves) when removed from the posterior ridge that gives it a “roman nose” lateral profile water, exposing its cantaloupe-colored foot and mantle (1). The ventral margin (2) is usually flat or slightly cavity. indented. The valves are moderately inflated (3), giving it Similar Species in Massachusetts: Brook floater shells a swollen appearance in cross section. The periostracum (dead animals) can be identified without difficulty, (4) is yellowish-green in young animals to brownish-black although sometimes are confused with the creeper, which in mature specimens and usually has prominent green rays has a similar shape and poorly developed pseudocardinal (5). Rays are often obscure in heavily eroded or stained teeth. Accurate identification of live animals usually relies shells. The diagnostic feature for this species is a series of on the corrugations on the shell, shape of the animal, corrugations (or raised ridges) along the dorso-posterior cantaloupe-colored foot, and its habit of gaping when slope (6), perpendicular to the growth lines; these removed from the water. Live juveniles or highly eroded corrugations are difficult to discern on shells that are adult brook floater, triangle floater, and creeper can young, eroded, stained, or covered with algae. -

Freshwater Mussels of Iowa

FRESHWATER MUSSELS OF IOWA Cedar Valley Resource, Conservation & Development, Inc. Printed 2002 THE FRESHWATER MUSSELS OF IOWA This mussel information guide was produced through the efforts of the Iowa Mussel Team in cooperation with the following sponsors: Iowa Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Agency Cedar Valley Resource Conservation and Development mussel photos: Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign riparian photo: Lynn Betts, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service life cycle diagram: Mississippi River, Lower St. Croix Team, Wisconsin Dept. Natural Resources cover photo: Mike Davis, Minnesota Dept. Natural Resources information compiled by Laurie Heidebrink review: Barb Gigar, Scott Gritters, and Tony Standera, Iowa DNR Cedar Valley R, C & D, Inc. 619 Beck Street, Charles City, IA 50616 641/257-1912 Equal Opportunity USDA prohibits deiscrimination in its programs on the basis of race, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, and marital or family status. USDA is an equal opportunity employer. Importance of Mussels This stable microhabitat is home to many Freshwater mussels may not be the first animal different species, all of which contribute to the that comes to mind when you think of Iowa’s river ecosystem. Algae growing on mussels are rivers, but they are very important to stream food for small fish and invertebrates, which are ecology and biodiversity. eaten by larger fish. Crayfish often convert mussel shells into a suitable home. Mussel beds They were an important food source for Native also provide spawning areas for many game fish. Americans, and still are for many animals–fish, turtles, mink, otters, and raccoons. Mussels also History of Mussels filter algae and other microscopic organisms Prior to the start of the 20th Century, mussel from the water; what they don’t digest is spit beds carpeted miles of river bottom from bank to back out as mucous plugs–a tasty meal for bank in some places. -

Federally Listed Species Information Presented in This Draft Report Is Considered Under Development. It May Be Incomplete and Is

DRAFT DRAFT SEPTEMBER 20, 2013 Federally Listed Species Information presented in this draft report is considered under development. It may be incomplete and is likely unedited. This may make some sections difficult to follow. An updated version if this report will be posted when it becomes available. ANIMALS Ten federally-endangered (E) or threatened (T) wildlife species are known to occur on or immediately adjacent to the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests (hereafter, the Forest). These include four small mammals, two terrestrial invertebrates, three freshwater mussels, and one fish (Table 1). Additionally, two endangered species historically occurred on or adjacent to the Forest, but are considered extirpated from North Carolina and are no longer tracked by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (Table 1). Table 1. Federally-listed wildlife species known to occur or historically occurring on or immediately adjacent to the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. Common Name Scientific Name Federal Status Small Mammals Carolina northern flying squirrel Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus Endangered gray myotis Myotis grisescens Endangered Virginia big-eared bat Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus Endangered Indiana bat Myotis sodalis Endangered Terrestrial Invertebrates spruce-fir moss spider Microhexura montivaga Endangered noonday globe Patera clarki Nantahala Threatened Freshwater Mussels Appalachian elktoe Alasmidonta raveneliana Endangered little-wing pearlymussel Pegius fabula Endangered Cumberland bean Villosa trabilis Endangered -

Alasmidonta Varicosa) Version 1.1.1

Species Status Assessment Report for the Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) Version 1.1.1 Molunkus Stream, Tributary of the Mattawamkeag River in Maine. Photo credit: Ethan Nedeau, Biodrawversity. Inset: Adult brook floaters. Photo credit: Jason Mays, USFWS. July 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service This document was prepared by Sandra Doran of the New York Ecological Services Field Office with assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Brook Floater Species Status Assessment (SSA) Team. The team members include Colleen Fahey, Project Manager (Species Assessment Team (SAT), Headquarters (HQ) and Rebecca Migala, Assistant Project Manager, (Region 1, Regional Office), Krishna Gifford (Region 5, Regional Office), Susan (Amanda) Bossie (Region 5 Solicitor's Office, Julie Devers (Region 5, Maryland Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Jason Mays (Region 4, Asheville Field Office), Rachel Mair (Region 5, Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery), Robert Anderson and Brian Scofield (Region 5, Pennsylvania Field Office), Morgan Wolf (Region 4, Charleston, SC), Lindsay Stevenson (Region 5, Regional Office), Nicole Rankin (Region 4, Regional Office) and Sarah McRae (Region 4, Raleigh, NC Field Office). We also received assistance from David Smith of the U.S. Geological Survey, who served as our SSA Coach. Finally, we greatly appreciate our partners from Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, the Brook Floater Working Group, and others working on brook floater conservation. Version 1.0 (June 2018) of this report was available for selected peer and partner review and comment. Version 1.1 incorporated comments received on V 1.0 and was used for the Recommendation Team meeting. This final version, (1.1.1), incorporates additional comments in addition to other minor editorial changes including clarifications. -

Strategic Plan 2012‐2017

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ecological Services Asheville, North Carolina Field Office STRATEGIC PLAN 2012‐2017 THE U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, WORKING WITH OTHERS, CONSERVES, PROTECTS, AND ENHANCES FISH, WILDLIFE, AND PLANTS AND THEIR HABITATS FOR THE CONTINUING BENEFIT OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND______________________________________3 STRATEGIC PLAN GOALS AND OBJECTIVES_______________________________8 AFO STAFFING AND DIVERSITY PLAN____________________________________13 APPENDIX A: AFO STRATEGIC PLAN PRIORITY WORK AREA MAP/GIS METHODOLOGY__18 MAP OF AFO STRATEGIC PLAN (FIGURE 2)_______________________________33 APPENDIX B: ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES FOR WHICH AFO HAS RESPONSIBILITIES__________________________________________________________34 APPENDIX C: REFERENCES AND CITATIONS______________________________38 APPENDIX D: STAFF ACTION PLANS_________________________________________52 APPENDIX E: TABLE OF ACRONYMS_____________________________________79 2 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service) Asheville Field Office (AFO), an Ecological Services facility, was established in the late 1970s. Forty-one counties make up the AFO’s core work area in western North Carolina, which includes many publicly owned conservation lands, especially in the higher elevations, as well as the metropolitan areas of Charlotte, Winston- Salem, and Asheville (Figure 1). This area primarily encompasses portions of the Blue Ridge and Piedmont physiographic provinces. In addition