Ian Flood Research Methods Course 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Findings and Decision by the Design Commission Rendered on May 18, 2017

FINAL FINDINGS AND DECISION BY THE DESIGN COMMISSION RENDERED ON MAY 18, 2017 The Design Commission has approved a proposal in your neighborhood. This document is only a summary of the decision. The reasons for the decision, including the written response to the approval criteria and to public comments received on this application, are included in the version located on the BDS website http://www.portlandonline.com/bds/index.cfm?c=46429. Click on the District Coalition then scroll to the relevant Neighborhood, and case number. If you disagree with the decision, you can appeal. Information on how to do so is included at the end of this decision. CASE FILE NUMBER: LU 16-285161 DZM AD PC # 16-175010 5 MLK BUREAU OF DEVELOPMENT SERVICES STAFF: Benjamin Nielsen 503-823-7812 / [email protected] GENERAL INFORMATION Applicant/ Representative: Kurtis Fusaro, Gerding/Edlen Development Company Inc 1477 NW Everett St Portland, OR 97209 Owner on Record: MKB Investment Co PO Box 325 Colton, OR 97017 Site Address: 5 SE Martin Luther King Jr Blvd Legal Description: BLOCK 77 LOT 1 EXC PT IN ST LOT 2, EAST PORTLAND; BLOCK 77 LOT 3&4 EXC PT IN STS, EAST PORTLAND; BLOCK 77 LOT 5 EXC PT IN ST, EAST PORTLAND; BLOCK 77 LOT 6 EXC PT IN ST, EAST PORTLAND; BLOCK 77 LOT 7 EXC PT IN ST LOT 8 EXC PT IN STS, EAST PORTLAND Tax Account No.: R226505110, R226505130, R226505150, R226505160, R226505170 State ID No.: 1N1E34DD 00500, 1N1E34DD 00400, 1N1E34DD 00300, 1N1E34DD 00200, 1N1E34DD 00100 Quarter Section: 3030 Neighborhood: Buckman, contact Rick Johnson at [email protected] Business District: Central Eastside Industrial Council, contact Debbie Kitchin at [email protected]. -

Portland's Artisan Economy

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning 1-1-2010 Brew to Bikes: Portland's Artisan Economy Charles H. Heying Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Entrepreneurial and Small Business Operations Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Heying, Charles H., "Brew to Bikes: Portland's Artisan Economy" (2010). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 52. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/52 This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Brew to bikes : Portland's artisan economy Published by Ooligan Press, Portland State University Charles H. Heying Portland State University Urban Studies Portland, Oregon This material is brought to you for free and open access by PDXScholar, Portland State University Library (http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/9027) Commitment to Sustainability Ooligan Press is committed to becoming an academic leader in sustainable publishing practices. Using both the classroom and the business, we will investigate, promote, and utilize sustainable products, technolo- gies, and practices as they relate to the production and distribution of our books. We hope to lead and encour- age the publishing community by our example. -

Social/Neighborhood Technical Report

Social/Neighborhood Technical Report Multnomah County | Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Project Portland, OR January 29, 2021 Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Social/Neighborhood Technical Report Prepared for Multnomah County Transportation Division – Bridges 1403 SE Water Ave Portland, OR 97214 Prepared by HDR 1050 SW 6th Ave, Suite 1800 Portland, OR 97204 T (503) 423-3700 Parametrix 700 NE Multnomah St, Suite 1000 Portland, OR 97232 T (503) 233-2400 Contract# DCS-SVCSGEN-857-2019-conv HDR Project #10144814 The technical material and data contained in this document were prepared under the supervision and direction of the undersigned, as a professional environmental specialist and urban planner. ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Prepared by Justina Everhart (Environmental Planner) ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Checked by Jeff Heilman (NEPA Lead) ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Approved by Heather Catron (Consultant Project Manager) Social/Neighborhood Technical Report Multnomah County | Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Project Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Project Location ........................................................................................................................ -

Adopt Framework Plan for Burnside Bridgehead

PORTLAND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION Portland, Oregon RESOLUTION NO. 6800 ADOPT THE FRAMEWORK PLAN AND ITS VISION AND PRINCPLES AS THE GUIDING DOCUMENT FOR THE EVALUATION OF FUTURE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BURNSIDE BRIDGEHEAD PROPERTY LOCATED ON BLOCKS 67, 68, 76, AND PORTIONS OF BLOCKS 69 AND 75, AT THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF NE MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. BLVD. AND E. BURNSIDE STREET IN THE CENTRAL EASTSIDE URBAN RENEWAL AREA. WHEREAS, on August 27, 1986, City Council Ordinance No. 158940 adopted the Central Eastside Urban Renewal Plan (the “Plan”) and the goals of the Plan emphasize revitalization, retention, and new business development and access to the river; WHEREAS, on February 17, 1999 (Resolution No. 5228), the Portland Development Commission’s (“PDC’s”) Board of Commissioners (the “Board”) adopted the Eastbank at Burnside: Lower East Burnside Redevelopment Plan (the “Eastbank at Burnside Plan”), which emphasizes a mixed-use gateway project at the foot of the Burnside Bridge in the Central Eastside Urban Renewal Area (the “URA”); WHEREAS, PDC acquired Blocks 67, 68, and 76, and portions of Blocks 69 and 75 in the URA (collectively, the “Burnside Bridgehead Property”) to implement the Eastbank at Burnside Plan; WHEREAS, the City of Portland’s Economic Development Strategy, a Five-Year Plan for Promoting Job Creation and Economic Growth, identifies the Burnside Bridgehead Property as a key catalytic site within the Central City and calls for the creation of a significant mixed-use gateway development at this location; WHEREAS, PDC entered into a -

Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge: Draft Environmental Impact

Environmental Justice Technical Report Multnomah County | Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Project Portland, OR January 29, 2021 Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Environmental Justice Technical Report Prepared for Multnomah County Transportation Division – Bridges 1403 SE Water Ave Portland, OR 97214 Prepared by HDR 1050 SW 6th Ave, Suite 1800 Portland, OR 97204 T (503) 423-3700 Parametrix 700 NE Multnomah St, Suite 1000 Portland, OR 97232 T (503) 233-2400 Contract# DCS-SVCSGEN-857-2019-conv HDR Project #10144814 CERTIFICATION The technical material and data contained in this document were prepared under the supervision and direction of the undersigned, as a professional environmental technical specialist. ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Prepared by Eduardo Montejo (Transportation Planner) ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Checked by Jeff Heilman (NEPA Lead) ______________ Signature Reserved for Final Version Approved by Heather Catron (Consultant Project Manager) Environmental Justice Technical Report Multnomah County | Earthquake Ready Burnside Bridge Project Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Project Location ........................................................................................................................ -

Notice of a Type II Decision on a Proposal in Your Neighborhood

Date: October 12, 2017 To: Interested Person From: Benjamin Nielsen, Land Use Services 503-823-7812 / [email protected] NOTICE OF A TYPE II DECISION AND NOTICE OF A TENTATIVE APPEAL HEARING DATE ON A PROPOSAL IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD The Bureau of Development Services has approved a proposal in your neighborhood. The mailed copy of this document is only a summary of the decision. The reasons for the decision are included in the version located on the BDS website http://www.portlandonline.com/bds/index.cfm?c=46429. Click on the District Coalition then scroll to the relevant Neighborhood, and case number. If you disagree with the decision, you can appeal. Information on how to do so is included at the end of this decision. If this case is appealed, the hearing for the appeal will be held Thursday, November 2, 2017 @ 1:30p.m. with the Design Commission. The hearing will take place in Room 2500A, 1900 SW 4th Avenue, Portland, OR 97201. If a timely and valid appeal is filed by the end of the appeal period at 4:30pm on October 26, 2017, no supplemental mailed hearing notice will be sent. If appealed, the appeal will be listed on the online Design Commission hearing agenda no later than 5pm on Friday, October 27, 2017. Online hearing schedules are available on the BDS web page (www.portlandoregon.gov/bds → Zoning/Land Use → Notices, Hearings, Decisions… → Public Hearings → Design Commission Agenda). Copies of the appeal filing will be available by contacting the case planner, Benjamin Nielsen (contact info. -

January 2013

STAR The Hollywood Publishing, Inc. NEWNEWSS H ServingStar North/Northeast Metro Portland Neighborhoods H H January 2013 H Volume 30, Number 7 H Getting personal about fitness By Jamie Caulley It’s January, which means you may have set a fitness goal for yourself. It also means the holiday festivities are over; the days are dark; and, chances are, you need help reaching your fitness goal. To increase the likelihood of success, consider working with a personal trainer. Personal trainers can help in three key ways: education, motivation and accountability. At Edge Performance Fitness in North Education Portland, client education focuses on func- Becoming educated is the first step in tion. The Edge contains no weight machines; getting started towards your fitness goal. instead, clients use various pieces of equipment George Comalli, long-time owner of Hol- such as kettle balls, TRX ropes and agility box- lywood Fitness on Northeast Sandy Boule- es to meet their fitness goals. New members vard, believes trainers can educate clients on complete a free functional movement screening how far they are from meeting their fitness that helps the trainer identify and educate the goals and help them “set a realistic goal with client on the best way to meet their needs. a realistic timeframe.” “It’s important to our staff that everyone Clients at Hollywood Fitness complete finds their home here, whether it be in a chal- an initial fitness assessment with a trainer lenge class or one on one (with a personal who tests key muscle groups and provides trainer),” said operations and marketing man- education on proper lifting technique and ager Robyn McGillis. -

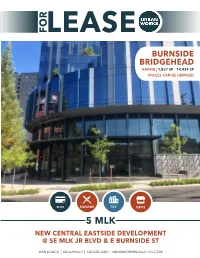

Burnside Bridgehead Range | 1,837 Sf - 14,434 Sf Spaces Can Be Demised

BURNSIDE BRIDGEHEAD RANGE | 1,837 SF - 14,434 SF SPACES CAN BE DEMISED RETAIL RESTAURANT FLEX SERVICE 5 MLK NEW CENTRAL EASTSIDE DEVELOPMENT @ SE MLK JR BLVD & E BURNSIDE ST DAN BOZICH | KIA HARTLEY | 503.228.3080 | URBANWORKSREALESTATE.COM 5 MLK | 1 5 MLK Retail Space fronting MLK Jr Blvd Address 5 SE MLK Jr Blvd Area Range Central Eastside / 1,837 SF - Burnside Bridgehead 14,434 SF Uses Retail / Restaurant / Flex / Service Retail New Central Eastside Development 5MLK is located at the signalized corner of E Burnside St and NE MLK Jr Blvd. This building is poised to anchor the Burnside Bridgehead, one of Portland’s most walkable and desirable neighborhoods. The 17 story tower features 220 apartment units, 120,000 SF of office and 14,434 SF of ground floor retail. Retail spaces front NE MLK Jr. Blvd, as well as a signature glass corner opportunity at the newly signalized intersection of SE Ankeny St & SE 3rd Ave. Corner Opportunity @ SE 3rd Ave & Ankeny St 5 MLK | 2 SITE PLAN E Burnside St Lower Level Plan: Parking & Retail SE MLK Jr Blvd SE MLK Ave rd SE 3 RETAIL 1 4,474 SF Outdoor Seating or Display Area SE Ankeny St E Burnside St Level 1 Plan: Lobby & Retail Retail Layout Options: SE MLK Jr Blvd SE MLK Vertical transportation RETAIL 3 required to combine Ave 1,837 SF rd Retail 1 with Retail 2 & SE 3 Retail 3 RETAIL 2 8,123 SF Outdoor Seating or Display Area SE Ankeny St 5 MLK | 3 RETAIL 1: FLOOR PLAN & SPECS About The Space • Signature opportunity for restaurant or traditional retail • Towering 26’4” ceiling height • Floor to ceiling