Are the Current World Anti-Doping Agency Guidelines Morally Justifiable? an Overview of Ethical Considerations and Possible Alternatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facing up to Reflections in German Print Media on Doping Scandal

SHS Web of Conferences 50, 01127 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185001127 CILDIAH-2018 “Doping Shadow Still Hard to Escape“: Facing up to Reflections in German Print Media on Doping Sсandal Aleksandr Pastukhov* Orel State Institute of Culture, Department Foreign Languages, 15, ul. Leskova, Orel, 302020 Russia Abstract. The paper reflects important features and developments of doping affair with Russian sportsmen as a media scandal. This communicative event is introduced through the current examples taken from the German national and regional press. The mechanisms of the formation and topicalization of the event are revealed in the paper. The global context of the scandal is covered and exampled by co-referential areas "Sport" and "Olympics". Their presentation and interpretation occur under conditions of so-called "fake news" and "media performance" strategies. The examples presented in chronological order reflect the communicative dynamics of the media event ‘doping scandal’. The remarkable features of the distinguishing journalistic style and informative media genres are covered in the paper. 1 Introduction mainly focus of attention. The emerging 'media' do not orient in the media space (not even because of the The "suppliers" of collective knowledge, or phenomenon of 'filter bubbles'), but are, at the same intermediaries in its dissemination, are mass time, 'echo chambers', which is completely new. We communication and mass media that never remain know that print media, TV, the Internet with hundreds of indifferent to what is mediated. The information about channels make everyone be confined in the popular the world is actualized in communication in strict media in the content net of what they like or dislike. -

A Multi-Level Legitimacy Analysis of the World Anti-Doping Agency

A Multi-Level Legitimacy Analysis of the World Anti-Doping Agency Read, Daniel Jonathan1, Skinner, James1; Lock, Daniel2 and Houlihan, Barrie1 1: Loughborough University, United Kingdom; 2: Bournemouth University, United Kingdom [email protected] Aim The effectiveness of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) as an international non- governmental organisation purposed to create and regulate anti-doping policy has been challenged by continued doping scandals in sport. Based on WADA’s response to the exposure of state sponsored doping in Russia, the purpose of this paper is to use multi-level legitimacy theory to understand reactive policy making in anti-doping. Theoretical Background and Literature Review Multi-level legitimacy theory (Bitektine & Haack, 2015) suggests that organisations conform to institutional pressures not necessarily because they agree with them, but because they can either profit from conforming or avoid reputational damage from challenging the dominant consensus. The result is that organisations true beliefs about the legitimacy of an institution may be suppressed until an event occurs which presents an opportunity to express views that challenge the status quo. Research suggests that anti-doping policy creation has been reactively prioritised after key events (Brissonneau & Ohl, 2010; Ritchie & Jackson, 2014). It is recognised that in the creation of WADA as an institution, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) lost their monopoly over anti-doping policy in sport due to government intervention after the Festina scandal (Hanstad, Smith & Waddington, 2008). It is argued that following the creation of WADA, organisations conformed to avoid reputational damage because failure to do so would signify to stakeholders that they were not concerned about doping in sport. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Facts and Introduction Corporate Manufacturing Products Markets Personnel Communication Figures speech Governance Policy Policy CONTENTS Facts and Figures Introduction speech by the Chairmen of the Council and Board Corporate Governance Manufacturing Products Markets Personnel Policy Communication Policy “Grindeks” Group – JSC “Grindeks” and five its subsidiary companies – JSC “Tallin Pharmaceutical plant” in Estonia, JSC “Kalceks” in Latvia, “Namu Apsaimniekošanas projekti” Ltd in Latvia, “Grindeks Rus” Ltd in Russia and “HBM Pharma” Ltd in Slovakia Core business – research, development, manufacturing and sales of original products, generics and active pharmaceutical ingredients Turnover – 105.4 million euros Net profit – 9.5 million euros Investments – 5.5 million euros Gross profit margin – 55% Net profit margin – 9% Export volume – 95.7 million euros Export countries – 71 Main markets – European Union, Russia and other CIS countries, USA, Canada, Japan and Vietnam FACTS AND FIGURES OF 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 SALES OF FINAL DOSAGE FORMS Final dosage forms sales volume – 97.5 million euros Sales volume in Russia, other CIS countries and Georgia – 58.2 million euros Sales volume in the Baltic States and other countries – 39.3 million euros TOP products – meldonium, tegafurum, zopiclone, risperidone, ipidacrine, oxytocin, pain relief ointments and dietary supplementsApilak-Grindeks. SALES OF ACTIVE PHARMACEUTICAL INGREDIENTS (API'S) Sales volume of API's – 6.3 million euros Offered 17 API's The most demanded API's of “Grindeks” – oxytocin, zopiclone, droperidol, detomidine, and pimobendan. QUALITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL “Good Manufacturing Practice” certificates for manufacturing of final dosage forms and active pharmaceutical ingredients ISO 9001; ISO 14001; LVS OHSAS 18001 certificates Russian ГОСТ ISO 9001-2011 certificate LVS EN ISO 50001:2012 Energy management certificate FACTS AND FIGURES OF 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 achievements, the greater our ability to invest in further business growth. -

Maciej Łuczak Oszustwo Dopingowe W Sporcie Wyczynowym

ROZPRAWY NAUKOWE Akademii Wychowania Fizycznego we Wrocławiu 2018, 60, 118 – 134 Maciej Łuczak Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego w Poznaniu OSZUSTWO DOPINGOWE W SPORCIE WYCZYNOWYM WśRÓD KOBIET W LATACH 1950–2017 Cel badań. W artykule przedstawiono zjawisko dopingu kobiet w sporcie w XX i XXI w. Wśród sportsmenek sztuczne wspomaganie wykryto w latach 50. XX w. W niektórych krajach powstał system maskowania dopingu przez władze państwowe. Doświadczenie w zakresie opracowywania i podawania leków wspomagających miały laboratoria antydopingowe, m.in. w Kreischa w NRD. Stosowanie niedozwolonych praktyk ukazano na przykładzie NRD, RFN, ZSRR, Chin, USA, Kenii i Polski. Materiał i metody. Materiał badawczy został zinterpretowany przy użyciu metod stoso- wanych w naukach historycznych: indukcyjnej, dedukcyjnej, komparatystycznej i analizy litera- tury specjalistycznej. Do sformułowania ostatecznych wniosków wykorzystano metodę syntezy. Wyniki. Praktyki dopingowe miały miejsce w wielu krajach. Od 1956 r. notuje się stosowanie wspomagania organizmów sportsmenek za pomocą testosteronu. Z czasem doszły bardziej udo- skonalone niedozwolone środki oraz metody, takie jak np. doping ciążowy. Najbardziej zorganizo- wany doping pod kuratelą państwa miał miejsce w NRD, RFN, ZSRR, Chinach, USA, Kenii i w Polsce. Wnioski. W latach 50. XX w. zawodniczki – zwłaszcza w Związku Radzieckim – spo- radycznie przyjmowały testosteron oraz steroidy anaboliczno-androgenne. Później liczba stoso- wanych środków dopingujących systematycznie rosła. Na większą skalę zaczęto je przyjmować dopiero w latach 70. i 80. XX w. Próbą zapanowania nad tym zjawiskiem są badania antydopin- gowe, jednak chęć zwycięstwa często przeważa nad zdrowym rozsądkiem. Słowa kluczowe: sport, doping, historia, kobiety WprowadzEniE Doping w sporcie znany jest od bardzo dawna. Zapewne byłby łatwiejszy do wykrycia, gdyby nie korzyści płynące z niego dla firm farmaceutycznych, lekarzy, trenerów, za- wodników, federacji sportowych oraz polityków i rządów państw. -

Meet the New Sophomores Olympics in Review

1 So there's no ignoring the fact that she's Canadian. I mean, she's got the accent, eh? But since I've gotten to know more about her and what her home is like, I've realized that I know next to nothing about our Fresh Faces: Meet the neighbors to the north (I mean, can you name Canada's ten provinces and three territories?). She's taught me that some Canadian money has a scratch-n-sniff maple New Sophomores leaf that smells like maple syrup, and meanwhile I'm wondering why our money doesn't smell like fried So, by now I think we all at least know the names chicken or apple pie. of...most of the new kids. But it’s about time for some of us to really get to know them. The FLASH is here to help Here are a few of Megan’s favorites: you strike up a conversation. Sport: hockey Music genre: country Season: winter Movie: The Sound of Music Justin Goodin Book: Watership Down Krystal Sydow There’s a lot more to Megan than just “Canada!” Get to K: Where and when were you born? know her. If you haven’t already, say hi and introduce J: South Carolina in 2001 yourself. She’s still getting used to some of the faces and K; What are some of your favorite pastimes and names here! hobbies? J: Playing basketball and schoolwork. K: Who is your favorite Prof? Timothy Meyer J: Prof Sullivan; he’s really funny. Jaq Gerbitz K: Do you have any special or hidden talents? J: Nope Some of us may simply refer to Timothy Meyer as Really? None at all? “Grace’s sister,” or “The well dressed, new kid.” But in Nope, nothing. -

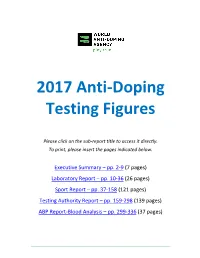

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Wozniacki of 13

SPORT Tuesday 26 September 2017 PAGE | 30 PAGE | 31 PAGE | 36 Dortmund out to Ronaldo struggles, Federer leads ruin Ronaldo’s superb Messi form Europe to maiden big day spark Ballon d’Or racee Laver Cup title 23rd Gulf Cup: Qatar in Group B The draw ceremony of Gulf Cup Football Tournament in progress in Doha yesterday. Pictures: Abdul Basit / The Peninsula Rizwan Rehmat Executive Committee members unity among thee fans,”fans,” he The Peninsula were also present. GULF CUP added. Officials from Saudi Arabia, Al Shaibani, Chairmanhairman of atar yesterday said it was the UAE and Bahrain did not the Gulf Competitionstions Com-Com- going ahead with its attend the draw ceremony. mittee, yesterday said tteamseams preparations to host the “Qatar is ready to organise that decide to boycottoycott the hugely popular Gulf Cup and host this tournament,” Jas- event could face fines.ines. Qfootball event which sim Al Rumaihi, General “We confirm that this scheduled to be held from Decem- Secretary of AGCFF, said tournament is thee firstfirst tour-tour- ber 22 to January 5. yesterday. nament to be heldd underunder thethe Also yesterday, officials of the “As of now, we are ready to supervision of thehe newly-newly- regional body, Arab Gulf Cup Foot- host the tournament. If we have formed AGCFF. Thehe ruleruless anandd ball Federation (AGCFF) expressed less number of teams, then the regulations have beenbeen pre-pre- confidence that the 23rd edition of event will be held on a round- pared with the approvalproval of aalllll the eight-nation event will feature robin format. -

<Vorname> <Nachname>

To the INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION - Members of the FIS Council Blochstrasse 2 - National Ski Associations 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee - Committee Chairwomen/Chairmen Switzerland Tel +41 33 244 61 61 Fax +41 33 244 61 71 Oberhofen, 4th June 2019 Summary of the FIS Council Meeting, 2nd June 2019, Cavtat-Dubrovnik (CRO) Dear Mr. President, Dear Ski Friends, In accordance with art. 32.2 of the FIS Statutes we have pleasure in sending you the Summary of the most important decisions from the FIS Council Meeting which took place on 2nd June 2019 in Cavtat-Dubrovnik (CRO). 1. Members present The following elected Council Members were present at the meeting in Cavtat- Dubrovnik (SUI) on Sunday, 2nd June 2019: President Gian Franco Kasper, Vice-Presidents Mats Arjes, Janez Kocijancic, Aki Murasato and Patrick Smith, Members: Andrey Bokarev, Steve Dong Yang, Dean Gosper, Alfons Hörmann, Hannah Kearney (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Roman Kumpost, Dexter Paine, Flavio Roda, Erik Roeste, Konstantin Schad (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Peter Schröcksnadel, Martti Uusitalo (by ‘phone), Eduardo Valenzuela and Michel Vion. Secretary General Sarah Lewis 2. Minutes from the Council Meeting in Oberhofen (SUI) November 2019 With the inclusion of a correction in the report on Tokyo 2020 (reference to currency Japanese yen instead of US dollars) requested by Vice-President Aki Murasato, the minutes from the Council Meeting in Oberhofen (SUI) from 16th November 2018 and the Gathering in Åre (SWE) from 13th February were approved. 3. The FIS World -

“Doping on a Hanger”: Regulatory Lessons from the FINA Elimination of the Polyurethane Swimsuit Applied to the International Anti-Doping Paradigm

“Doping on a Hanger”: Regulatory Lessons from the FINA Elimination of the Polyurethane Swimsuit Applied to the International Anti-Doping Paradigm RACHEL MACDONALD* In 2008, swimwear manufacturer Speedo released the world‟s first polyurethane competition body suit, the LZR Racer. Compared to “doping on a hanger,” the suit was an unprecedented leap in swimsuit technology, and more than 130 world records were broken in only the first seventeen months after the LZR became available to competitive swimmers. Upon realizing the polyurethane swimsuits stood to radically change swimming, the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA) implemented regulation that swiftly and successfully eradicated the problem. In contrast, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has yet to effectively control athletic doping. Focus on the international anti-doping regime intensified in 2014 upon the exposure of widespread, permissive doping among internationally competitive Russian athletes. Further, WADA statistics reveal doping remains a serious and growing problem. Despite the different scopes and missions of FINA and WADA, there are several regulatory lessons that can be extracted from FINA‟s successful polyurethane swimsuit ban and applied to WADA‟s struggle to eliminate doping in sports. The goal of this Note is to compare the international doping problem and the polyurethane swimsuit ban and then to ascertain how the successful FINA regulatory paradigm might be applied to the international anti-doping regime. Ultimately, FINA‟s example suggests that WADA might benefit from making changes including: creating more specific regulations that can be articulated and then applied in a * Articles Editor, Colum. J.L. & Soc. Probs., 2017–2018. J.D. -

The Effects of Meldonium on the Acute Ischemia/Reperfusion Liver Injury in Rats

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The efects of meldonium on the acute ischemia/reperfusion liver injury in rats Siniša Đurašević1*, Maja Stojković2, Jelena Sopta2, Slađan Pavlović3, Slavica Borković‑Mitić3, Anđelija Ivanović3, Nebojša Jasnić1, Tomislav Tosti4, Saša Đurović5, Jelena Đorđević1 & Zoran Todorović2,6 Acute ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) liver injury is a clinical condition challenging to treat. Meldonium is an anti‑ischemic agent that shifts energy production from fatty acid oxidation to less oxygen‑ consuming glycolysis. Thus, we investigated the efects of a 4‑week meldonium pre‑treatment (300 mg/kg b.m./day) on the acute I/R liver injury in Wistar strain male rats. Our results showed that meldonium ameliorates I/R‑induced liver infammation and injury, as confrmed by liver histology, and by attenuation of serum alanine‑ and aspartate aminotransferase activity, serum and liver high mobility group box 1 protein expression, and liver expression of Bax/Bcl2, haptoglobin, and the phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa‑light‑chain‑enhancer of activated B cells. Through the increased hepatic activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2‑related factor 2, meldonium improves the antioxidative defence in the liver of animals subjected to I/R, as proved by an increase in serum and liver ascorbic/dehydroascorbic acid ratio, hepatic haem oxygenase 1 expression, glutathione and free thiol groups content, and hepatic copper‑zinc superoxide dismutase, manganese superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase activity. Based on our results, it can be concluded that meldonium represent a protective agent against I/R‑induced liver injury, with a clinical signifcance in surgical procedures. Acute ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) refers to a temporary abolishment of blood fow during surgical interventions, followed by its re-establishment once an intervention is fnished 1. -

Analysis of Anti-Doping Rule Violations That Have Impacted

Sports Medicine https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01463-4 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Analysis of Anti‑Doping Rule Violations That Have Impacted Medal Results at the Summer Olympic Games 1968–2012 Alexander Kolliari‑Turner1,2 · Giscard Lima1,3 · Blair Hamilton1,2,4 · Yannis Pitsiladis1,2,3,5,6,7 · Fergus M. Guppy2,8 Accepted: 29 March 2021 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 Abstract Introduction Since 2004, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) store all samples collected at summer Olympic Games (OG) for retrospective re-analysis with more advanced analytical techniques to catch doping athletes. Methods All announced Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) from IOC re-tests of the 2004, 2008 and 2012 OG (via IOC, International Federations and Athletics Integrity Unit public data) and other ADRVs confrmed to impact OG results from 1968 to 2012 (via the list of Doping Irregularities on olympedia.org) were collated to investigate how many medals have been impacted by ADRVs, when the ADRV was identifed relative to the OG in question and its cause. Results One hundred and thirty-four medals were impacted by ADRVs but only 26% of these ADRVs were identifed at the time of the OG. Most ADRVs impacting medal results (74%) were identifed retrospectively, either from events prior to the OG (17%) or via IOC re-tests of samples from 2004, 2008 and 2012 (57%). ADRVs impacting medal results from these re-tests took a mean of 6.8 ± 2.0 years to be announced relative to the end of the OG in which the medal was originally won.