Ampleforth and Downside (English Benedictine Congregation Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS in North Yorkshire

HERITAGE CYCLE TRAILS Leaving Rievaulx Abbey, head back Route Two English Heritage in Yorkshire to the bridge, and turn right, in North Yorkshire continuing towards Scawton. Scarborough Castle-Whitby Abbey There’s always something to do After a few hundred metres, you’ll (Approx 43km / 27 miles) with English Heritage, whether it’s pass a turn toward Old Byland enjoying spectacular live action The route from Scarborough Castle to Whitby Abbey and Scawton. Continue past this, events or visiting stunning follows a portion of the Sustrans National Cycle and around the next corner, locations, there are over 30 Network (NCN route number one) which is well adjacent to Ashberry Farm, turn historic properties and ancient signposted. For more information please visit onto a bridle path (please give monuments to visit in Yorkshire www.sustrans.org.uk or purchase the official Sustrans way to horses), which takes you south, past Scawton Croft and alone. For details of opening map, as highlighted on the map key. over Scawton Moor, with its Red Deer Park. times, events and prices at English Heritage sites visit There are a number of options for following this route www.english-heritage.org.uk/yorkshire. For more The bridle path crosses the A170, continuing into the Byland between two of the North Yorkshire coast’s most iconic and information on cycling and sustainable transport in Yorkshire Moor Plantation at Wass Moor. The path eventually joins historic landmarks. The most popular version of the route visit www.sustrans.org.uk or Wass Bank Road, taking you down the steep incline of Wass takes you out of the coastal town of Scarborough. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

8Th-June-2014

SERVICE TIMES THIS WEEK OUR LADY and ALL SAINTS Lancaster Lane - Parbold - Lancashire - WN8 7HS Monday 9 June – Saint Columba 1100 Requiem Mass Web-site: <http://www.ourladysparbold.org.uk> Joe Lewis e-mail: [email protected] Priest: Father Gordon OSB Tuesday 10 June 01257-463248 0915 Morning Prayer with Mass Deacon: Rev David Bennett 01257-462998 Fred Johnston Notre Dame Convent 01257-465069 Wednesday 11 June – Saint Barnabas 1000 Requiem Mass Margaret Heffernan Thursday 12 June 1900 Evening Prayer with Mass Brian Wilson Friday 13 June – Saint Anthony of Padua OFM 0915 No Morning Prayer Celia Hitchen Saturday 14 June 1100 Morning Prayer with Mass English Benedictines 1135 Confessions Sunday 15 June – THE HOLY TRINITY Sunday 8 June 2014 Vigil Saturday Fathers Day 1800 Josef and Anna Wroblewski PENTECOST Sunday VIGIL 1800 Gerald Hitchen 1000 The Parish SUNDAY 1000 The Parish Please take this News Letter home with you Baptisms Matthew Graham Parr Ampleforth Abbey Trust – A Registered Charity No. 1026493 Abigail Erika Parr Ava-Violet Faith Cheetham LEASE PRAY FOR: SUMMER FAIR .FATHER BARRY REGINA COELI the Sick: There will be a Summer Fair/ Father Barry’s personal from Easter until Pentecost Jean Benyon Family Picnic at Parbold Hall on e-mail address has been Sunday 15 June. changed. It is now O Queen of heaven, rejoice! those who have died recently: [email protected] Alleluia. Joe Lewis This will be run by the School Note two tt’s in matthews. For he whom you did merit to Requiem 1100 Monday 9 June and the Parish. bear. Alleluia. -

Gilthorpe Abbey Park, Ampleforth, York Yo62 4Df

Gilthorpe Abbey pArk, Ampleforth, york yo62 4Df Distances: helmsley 5 miles, thirsk 13 miles, york 22 miles AN eXCeptioNAl 5 beDroom fAmily home Set iN the beAUtifUl SUrroUNDS of Ampleforth, North yorkShire Accommodation and Amenities entrance hall, open plan kitchen/ breakfast/family room, sitting room, study/playroom, dining room, WC, utility room master bedroom ensuite with dressing room, Guest bedroom with ensuite and 3 further bedrooms and a house bathroom Detached double garage priVate enclosed garden Introduction This 5 bedroom detached home is fnished to an exceptionally high standard and sits in the beautiful village of Ampleforth. the house is extremely spacious, light and well planned. the superb kitchen, breakfast, family room is ideal for modern family living room and has access into the garden. As well as this space there is a large sitting room and dining room, spacious hallway and a study (which could be used as a playroom/snug). Upstairs, the spacious bedrooms lead off a large landing area. there is a master bedroom ensuite with a dressing area as well as a guest bedroom with ensuite and three further good sized bedrooms and house bathroom. outside, the property has a detached double garage, as well as a generous priVate driVe; perfect for busy families with more than one car. Viewing is essential to appreciate this wonderful family home and its idyllic location. Environs Ampleforth is pretty village with a primary School, nursery, shop with Post Offce, tea rooms and two excellent pubs. it is also close to the stunning market town of helmsley and an easy driVe to the historic city of york. -

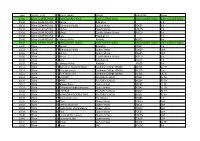

Time CLASS TITLE RIDER NAME Horse Name School School No

Time CLASS_TITLE RIDER_NAMEHorse_Name School School No Team 09:00 60cm COURSE WALK 60cm60cm COURSE COURSE WALK WALK 60cm COURSE WALK 60cm COURSE WALK 60cm COURSE WALK 09:30 60cm CLEAR ROUND DaisyZarnia Tinkler Rillington Ind 09:32 60cm CLEAR ROUND FloGlenshane Penny-Smith Paddy Queen Marys TO625 Ind 09:34 60cm CLEAR ROUND FranShirley Holland Queen Marys TO625 Ind 09:36 60cm CLEAR ROUND PeggyMissy Attwood Cundall Manor School A0210 Ind 09:38 60cm CLEAR ROUND SaffronLucy Verrill Hawsker C.E Ind 09:40 60cm CLEAR ROUND JoeMansty Lumley Millie Ryedale A0205 Ind 09:42 70cm COURSE WALK 70cm70cm COURSE COURSE WALK WALK 70cm COURSE WALK 70cm COURSE WALK 70cm COURSE WALK 10:00 70cm DaisyZarnia Tinkler Rillington A1837 Ind 10:02 70cm FloGlenshane Penny-Smith Paddy Queen Marys TO625 QM 10:04 70cm FranShirley Holland Queen Marys TO625 QM 10:06 70cm PeggyMissy Attwood Cundall Manor School A0210 Ind 10:08 70cm SaffronLucy Verrill Hawsker CE A1879 Ind 10:10 70cm JoeMansty Lumley Millie Ryedale A0205 Ind 10:12 70cm MaryBrynathan Agar Starlight Magic Caedmon College Whitby A1326 CC 70 10:14 70cm OliviaKillough Clarkson queen Caedmon College Whitby A1326 Ind 10:16 70cm RuthIrish Chadfield Texas Tom Caedmon College Whitby A1326 CC 70 10:18 70cm TESSJACKSON ARUNDEL FULFORD SCHOOL A1834 FS 70 10:20 70cm TILLYAPRIL ANDREW FULFORD SCHOOL A1834 FS 70 10:22 70cm AmeliaGlowonllinos Warrington Lady Lumleys A0141 LL 70 10:24 70cm CharlotteDeepmoordangerousliason Stockill Lady Lumleys A0141 LL 70 10:26 70cm ELLASAFFRON NASSON FULFORD SCHOOL A1834 FS 70 10:28 70cm -

Ex-British Prime Minister Received Into Catholic Church

Ex-British Prime Minister received into Catholic Church LONDON – Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair became a Catholic during a private ceremony in London. Mr. Blair, previously an Anglican, was received into full communion with the Catholic Church by Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor of Westminster. Mr. Blair was sponsored at the Mass of reception by his wife, Cherie, a Catholic. The Dec. 21 Mass at Archbishop’s House, the cardinal’s private residence, was attended by Mr. Blair’s family and close friends. Cardinal Murphy-O’Connor said in a statement Dec. 22 that he was “very glad” to welcome Mr. Blair into church. “For a long time he has been a regular worshipper at Mass with his family and in recent months he has been following a program of formation to prepare for his reception into full communion,” the cardinal said. “My prayers are with him, his wife and family at this joyful moment in their journey of faith together.” Mr. Blair, 54, served as British prime minister from May 1997 until June 2007. He now serves as envoy to the Middle East for the Quartet, a group comprised of the United Nations, the European Union, the United States and Russia. He was admitted into the church using the liturgical rite of reception of a baptized Christian, which involved him making a profession of faith during the course of the Mass. He was given doctrinal and spiritual preparation by Monsignor Mark O’ Toole, the cardinal’s private secretary, and also made a full confession before his reception. For most of his adult life, Mr. -

“The Power of the Trinity in the World and in Our Lives”

“THE POWER OF THE TRINITY IN THE WORLD AND IN OUR LIVES” National Catholic Student Coalition Conference Albuquerque, New Mexico - December 31, 1999 Welcome to New Mexico, the land of enchantment! In 1912 New Mexico finally became a state of the Union; it was the last of the forty-eight contiguous states to become a state. For sixty- two years officials of New Mexico had sought statehood, but it was thought in Washington that New Mexico was too dusty, too uncivilized and besides, most of the people here spoke Spanish. They thought we were too multi-cultural and multi-ethnic to become part of the United States. Now it is precisely those characteristics which give us our sense of pride. Not far from here is the small town of Espanola, known for its hot enchiladas, low-riders and bad jokes. There you will find one of the most charming accents of the English language –next to that of the Texas drawl and Brooklynese! Three men, a white, a black and a Chicano, are in a bar and a shapely blond walks in. They are immediately enthralled by her and keep eyeing her. Finally she walks over to them and says, “O.K., guys, I know you want to go out with me. Well, I can only go out with one of you. I will choose the one who can come up with the best sentence using the words, liver and cheese.” The white man says, “I just love liver and cheese sandwiches!” She responds with disgust, “That’s gross. Is that the best you can do? Let’s see what the others have to say.” The black man says, “I just hate liver and cheese sandwiches!” The blond shouts, “How awful! Your sentence is even worse that the first one!” She turns to the Chicano, and he, look the other two men says, “ Liver alone, cheese mine!” Guess who gets the blond, and guess where he’s from? From Espanola, of course! You have asked me to speak of the Trinity, ministry, young adults and the Catholic Church. -

Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham - Alexis Jay Report

Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham - Alexis Jay report Date 10 September 2014 Author Martin Rogers LGiU/CSN Associate Summary The report of the Independent Inquiry into child sexual exploitation (CSE) in Rotherham between 1997 and 2013, conducted by Alexis Jay OBE, was published by Rotherham Borough Council (which commissioned it) on 26 August 2014. The Leader of the Council resigned the same day, taking responsibility on behalf of the Council for the historic failings described in the report, and apologising to the young people and their families who had been so badly let down. The Chief Executive has now said he is leaving. The report has received widespread media coverage, with regular comment since its publication, including an urgent question (a request for a statement) in the House of Commons to Home Secretary Theresa May from her shadow, Yvette Cooper, on 2 September. The Commons Home Affairs Committee takes further evidence on child sexual exploitation in Rotherham on 9 September. This briefing contains a short summary of the report, and focuses more on the reaction to it and the implications for local authorities and their partners. It will be of interest to elected members and officers with responsibility for the broad range of services for children and young people, all of which have a role to play in identifying those at risk of sexual exploitation and in successful approaches to tackling it. Overview The Independent Inquiry commissioned by Rotherham Borough Council into child sexual exploitation (CSE), and conducted by Professor Alexis Jay OBE (previously Chief Social Work Adviser to the Scottish Government), found that a conservative estimate of 1,400 children were sexually exploited over the full Inquiry period from 1997 to 2013. -

Alpha: Another Road to Rome?

Alpha: Another Road To Rome? Commentary by Roger Oakland www.understandthetimes.org The Alpha program, founded by Nicky Gumbel, a former Oxford educated barrister-turned-Anglican priest has become very popular in North America. A brochure published for the Alpha Texas Conference in Austin, Texas, scheduled for January 8th and 9th, 1998 detailed the goals and objectives of the course. It stated: The Alpha Course is a ten-week practical introduction to the Christian faith. It is designed primarily for non-church goers and those who have recently become Christians. Alpha is a flexible and practical model that can work for a group of any size. Churches and Christian organizations of every background and denomination are discovering it to be a simple and effective way of presenting the gospel of Jesus Christ in a non- threatening manner for people of all walks of life.[1] Charisma, December 1999, also contained an article that provided additional information about the Alpha program and how it is being promoted and marketed. The article, written by journalist Clive Price titled “Alpha Course Supporters Urge British To Party With God On New Year’s Eve” was introduced the following way: Lying on a bed of nails? That does not sound like the most orthodox way of spearheading a $1.6 million evangelistic media campaign for the closing days of the twentieth century. But as British pastor Sandy Miller puts it, the aim of the Alpha Project’s millennium initiative is to help people “get the point” of the year 2000.[2] Although Nicky Gumbel’s Alpha course was founded at Holy Trinity Brompton in 1991, the effectiveness of the course was not realized until a few years later after the “Toronto Blessing” was transported to England from Canada in May of 1994. -

The Ampleforth Journal September 2018 to July 2019

The Ampleforth Journal September 2018 to July 2019 Volume 123 4 THE AMPLEFORTH JOURNAL VOL 123 Contents editorial 6 the ampleforth Community 8 the aims of arCiC iii 10 Working within the United nations Civil affairs department 17 Peace and security in a fractured world 22 My ampleforth connection 27 Being a Magistrate was not for me 29 the new testament of the revised new Jerusalem Bible 35 the ampleforth Gradual 37 the shattering of lonliness 40 Family of the raj by John Morton (C55) 42 right money, right place, right time by Jeremy deedes (W73) 44 the land of the White lotus 46 the Waterside ape by Peter rhys evans (H66) 50 Fr dominic Milroy osB 53 Fr aidan Gilman osB 58 Fr Cyprian smith osB 64 Fr antony Hain osB 66 Fr thomas Cullinan osB 69 richard Gilbert 71 old amplefordian obituaries 73 CONTENTS 5 editorial Fr riCHard FField osB editor oF tHe aMPleFortH JoUrnal here have been various problems with the publishing of the ampleforth Journal and, with the onset of the corona virus we have therefore decided to publish this issue online now without waiting for the printed edition. With the closure of churches it is strange to be celebrating Mass and singing the office each day in our empty abbey Church but we are getting daily emails from people who are appreciating the opportunity to listen to our Mass and office through the live streaming accessible from our website. on sunday, 15th March, about a hundred tuned in; a week later, there were over a thousand. -

Advent 2016 Dear Friends of St

Advent 2016 Dear Friends of St. Anselm’s, Here, as in many monasteries and churches throughout the world, we hear on each December 24 the sung proclamation of the birth of Christ as found in the Roman Martyrology. It begins with creation and relates Christ’s birth to the major events and personages of sacred and secular history, with references to the 194th Olympiad, the 752nd year from the foundation of the city of Rome, and the 42nd year of the reign of Octavian Augustus. The proclamation goes on to say that “the whole world was then at peace,” a fact that many early Christian preachers emphasized. Sadly, we cannot say that our entire world is at peace today, certainly not in Syria or other parts of the Middle East, and there are stark divisions in our own country over social and political issues. This makes it all the more incumbent on each of us to be peacemakers to the best of our ability as we take to heart the words of the Prince of Peace: “These things I have said to you that you may have peace. In the world you will have tribulation, but take courage—I have overcome the world” (John 16:33). The Monks of St. Anselm’s Abbey The Chronicler’s Column Late summer brought about a significant change to give encouragement and advice to monastic com- in the Benedictine Confederation worldwide when munities and congregations throughout the world, Abbot Notker Wolf stepped down after sixteen very especially in developing countries. successful years as abbot primate and was suc- Closer to home, our community retreat in mid-Au- ceeded by Abbot Gregory Polan, the former abbot gust was led by Fr Ezekiel Lotz, OSB, a monk of of Conception Abbey in Missouri. -

Barriers to Truth Recovery in the Aftermath of Institutional Child Abuse in Ireland

An Inconvenient Truth: Barriers to Truth Recovery in the Aftermath of Institutional Child Abuse in Ireland McAlinden, A-M. (2013). An Inconvenient Truth: Barriers to Truth Recovery in the Aftermath of Institutional Child Abuse in Ireland. Legal Studies, 33(2), 189-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-121X.2012.00243.x Published in: Legal Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:24. Sep. 2021 Legal Studies, 2012 DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-121X.2012.00243.x An inconvenient truth: barriers to truth recovery in the aftermath of institutional child abuse in Irelandlest_243 1..26 Anne-Marie McAlinden* School of Law, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland Contemporary settled democracies, including the USA, England and Wales and Ireland, have witnessed a string of high-profile cases of institutional child abuse in both Church and State settings.