LE CORBUSIER the Maison La Roche

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tropicalism Charlotte Perriand Oscar Niemeyer Zanine Caldas

TROPICALISM CHARLOTTE PERRIAND OSCAR NIEMEYER ZANINE CALDAS OCTOBER 11 - NOVEMBER 10, 2018 Oscar Niemeyer, untitled Collage © Tom Shapiro / Laffanour Galerie Downtown, Paris Press Contact : FAVORI - 233, rue Saint Honoré 75001 Paris – T +33 1 42 71 20 46 Grégoire Marot - Nadia Banian [email protected] 1 TROPICALISM CHARLOTTE PERRIAND OSCAR NIEMEYER ZANINE CALDAS OCTOBER 11 - NOVEMBER 10, 2018 CHARLOTTE PERRIAND & BRAZIL In 1959, Charlotte Perriand, in collaboration with Le Corbusier and Lucio Costa, did the layout of “ La Maison du Brésil ” in the “ Cité Internationale de Paris. ” In 1962, her husband Jacques Martin was appointed director of Air France for the Latin America region, so until 1969 he made frequent trips to Brazil. Thanks to Lucio Costa, she meets architects Oscar Niemeyer and Roberto Burle Max, who introduced her to the Tropicalism movement. It is a global cultural movement that takes the opposite of the West, mixing different disciplines such as music or furniture. He emerged in Brazil in 1967, during the period of military dictatorship (1964-1985), and aspired to revolutionize his time. It is for its actors to meet both unique climatic requirements, while using local materials, and adopting the typical forms of these countries of South America. Very inspired, Charlotte Perriand created furniture for her apartment and for some projects on the spot, taking the lines of her European furniture, but having them made in local woods (such as jacaranda, or Rio rosewood) with braiding of rushes or caning. Press opening on -

Le Corbusier's Cité De Refuge

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/LC2015.2015.796 Le Corbusier’s Cité de Refuge: historical & technological performance of the air exacte L.M. Diaz, R. Southall School of Arts, Design and Media, University of Brighton Abstract: Despite a number of attempts by Le Corbusier to implement the combination of ‘respiration exacte’ with the ‘mur neutralisant’ he was never able to test the viability of his environmental concepts in a realised building. The Cité de Refuge, which was built with a more conventional heating system and single glazed facade, is however unique in that unlike the other potential candidates for the implementation of these systems, the building, as built, retained a key design feature, i.e. the hermetically sealed skin, which ultimately contributed to the building’s now infamous failure. It is commonly argued that Le Corbusier, however, abandoned these comprehensive technical solutions in favour of a more passive approach, but it is less well understood to what extent technical failures influenced this shift. If these failures were one of the drivers for this change, how the building may have performed with the ‘respiration exacte’ and ‘mur neutralisant’ systems becomes of interest. Indeed, how their performance may have been improved with Le Corbusier's later modification of a brise-soleil offers an alternative hypothetical narrative for his relationship to technical and passive design methodologies. Keywords: environment, technology, performance, history, Cité de Refuge. 1. Introduction There are two technical building concepts that represent, perhaps more than any others Le Corbusier’s early drive to find comprehensive and exclusively mechanical approaches to the heating and ventilation of modern buildings: a) the mur neutralisant, a double-skin glazed wall with conditioned air circulated within the cavity to moderate heat exchange between the interior and exterior, and b) the respiration exacte, a mechanical ventilation system for providing conditioned air to interior spaces at a constant temperature of 18˚C. -

Freefrom: Jean Dubuffet, Simon Hantaï, Charlotte Perriand 2 February – 29 March 2018

Freefrom: Jean Dubuffet, Simon Hantaï, Charlotte Perriand 2 February – 29 March 2018 15 Carlos Place, London W1K 2EX T +44 20 7409 3344 [email protected] timothytaylor.com Jean Dubuffet Arbre Le Circonvole, 1970 Paint on polyester 25 1/4 × 19 3/4 × 16 1/8 in. 64 × 50 × 41 cm T0011291 Exhibitions Jean Dubuffet: Paintings, Gouaches, Assemblages, Sculpture, Monuments Practicables, Works on Paper, Waddington Galleries, London, UK 1972 Polychromie à travers les Ages et les Civilisations, Musée Bourdelle, Paris, France 1971 Jean Dubuffet Amoncellement à la Corne, 1968 Vinyl paint on epoxy resin 22 × 23 1/2 × 18 3/4 in. 55.8 × 59.6 × 41 cm T0011291 Exhibitions Jean Dubuffet: Peintures Monumentées, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, France 12 December 1968 – 8 February 1969 Jean Dubuffet Arbre Le Circonvole, 1970 Paint on polyester 25 1/4 × 19 3/4 × 16 1/8 in. 64 × 50 × 41 cm T0011291 Provenance David Rockefeller (a gift from the artist) Exhibitions Jean Dubuffet 1901-1985, Schirn Kunstalle, Frankfurt, Germany December 1990 – March 1991 Jean Dubuffet: A Retrospective, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA 1973 David Rockefeller with architectural model of the facade of 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza, New York showing the work. Jean Dubuffet Elément bleu III, 1967 Transfer on polyester 39 × 45 5/8 × 4 in. 99 × 116 × 10 cm T0011287 Exhibitions Jean Dubuffet: a Fine Line, Sotheby’s S|2, New York, USA May – June 2014 Jean Dubuffet, Waddington Galleries, London, UK 1972 (cat. p.23) L’oeil écoute : exposition international d’art contemporain, Palais des Papes, Avignon, France June – September 1969 Jean Dubuffet, Peintures Monumentèes, Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Paris, France 1968-69 Jean Dubuffet Paysage logologique, 1968 Transfer on polyester 19 1/4 × 33 1/8 × 35 3/8 in. -

Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum

1 Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum (by Hugh Grant, Founding Director and Curator, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art) Kirkland Museum’s decorative art collection contains more than 15,000 objects which have been chosen to demonstrate the major design styles from the later 19th century into the 21st century. About 3,500 design works are on view at any one time and many have been loaned to other organizations. We are recognized as having one of the most important international modernist collections displayed in any North American museum. Many of the designers listed below—but not all—have works in the Kirkland Museum collection. Each design movement is certainly a confirmation of human ingenuity, imagination and a triumph of the positive aspects of the human spirit. Arts & Crafts, International 1860–c. 1918; American 1876–early 1920s Arts & Crafts can be seen as the first modernistic design style to break with Victorian and other fashionable styles of the time, beginning in the 1860s in England and specifically dating to the Red House of 1860 of William Morris (1834–1896). Arts & Crafts is a philosophy as much as a design style or movement, stemming from its application by William Morris and others who were influenced, to one degree or another, by the writings of John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin. In a reaction against the mass production of cheap, badly- designed, machine-made goods, and its demeaning treatment of workers, Morris and others championed hand- made craftsmanship with quality materials done in supportive communes—which were seen as a revival of the medieval guilds and a return to artisan workshops. -

La Cité De Refuge Le Corbusier Et Pierre Jeanneret L’Usine À Guérir

Les Éditions du patrimoine présentent La Cité de refuge Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret L’usine à guérir Collection « Monographies d’édifices » > Le premier équipement collectif de Le Corbusier, classé Monument historique depuis 1975. > La restauration exemplaire d’un chef d’œuvre du XXe siècle. > Plus de 80 ans après sa construction, un centre d’accueil social toujours en activité. Contact presse : annesamson communications : Andréa Longrais - 01 40 36 84 32 – [email protected] Camille de La Vaquerie - 01 40 36 84 32 – [email protected] Éditions du patrimoine : [email protected] – 01 44 54 95 22 Clair Morizet : [email protected] - 01 44 54 95 23 1 Su -Lian Neville : [email protected] - 01 44 61 22 70 Communiqué de presse Commandée en 1929 par l’Armée du Salut à Le Corbusier et à son cousin Pierre Jeanneret sur une proposition de la princesse de Polignac, la Cité de refuge a été la première réalisation d’ampleur de l’architecte ; elle vient de faire l’objet d’une profonde restauration, menée sous la maîtrise d'ouvrage de Résidences Sociales de France. Conçu comme un centre d’accueil et d’hébergement de 282 lits pour sans-abris, ce vaste édifice remplit peu ou prou les mêmes fonctions 80 ans plus tard. Restaurer ce monument historique tout en s’adaptant à un environnement social et humain profondément bouleversé était un véritable pari. La Cité de refuge présente nombre d’innovations : il s’agissait ainsi du premier bâtiment d'habitation entièrement hermétique, comportant en particulier mille mètres carrés de vitrages sans ouvrant. -

Le Corbusier and Photography Author(S): Beatriz Colomina Source: Assemblage, No

Le Corbusier and Photography Author(s): Beatriz Colomina Source: Assemblage, No. 4 (Oct., 1987), pp. 6-23 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3171032 . Accessed: 22/08/2011 07:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Assemblage. http://www.jstor.org Beatriz Colomina Le Corbusier and Photography Beatriz Colomina is Adjunct Assistant The MechanicalEye Professorat Columbia Universityand a Consulting Editor of Assemblage. There is a still from Dziga Vertov'smovie "The Man with the MovieCamera" in whicha humaneye appearssuper- imposedon the reflectedimage of a cameralens, indicat- ing preciselythe point at which the camera- or rather, the conceptionof the worldthat accompaniesit - disso- ciatesitself from a classicaland humanistepisteme. The traditionaldefinition of photography,"a transparent presentationof a realscene," is implicitin the diagram institutedby the analogicalmodel of the cameraobscura - thatwhich wouldpretend to presentto the subjectthe faithful"reproduction" of a realityoutside itself. In this def- inition, photographyis investedin the systemof classical representation.But Dziga Vertovhas not placedhimself behindthe cameralens to use it as an eye, in the wayof a realisticepistemology. Vertov has employedthe lens as a mirror:approaching the camera,the firstthing the eye sees is its own reflectedimage. -

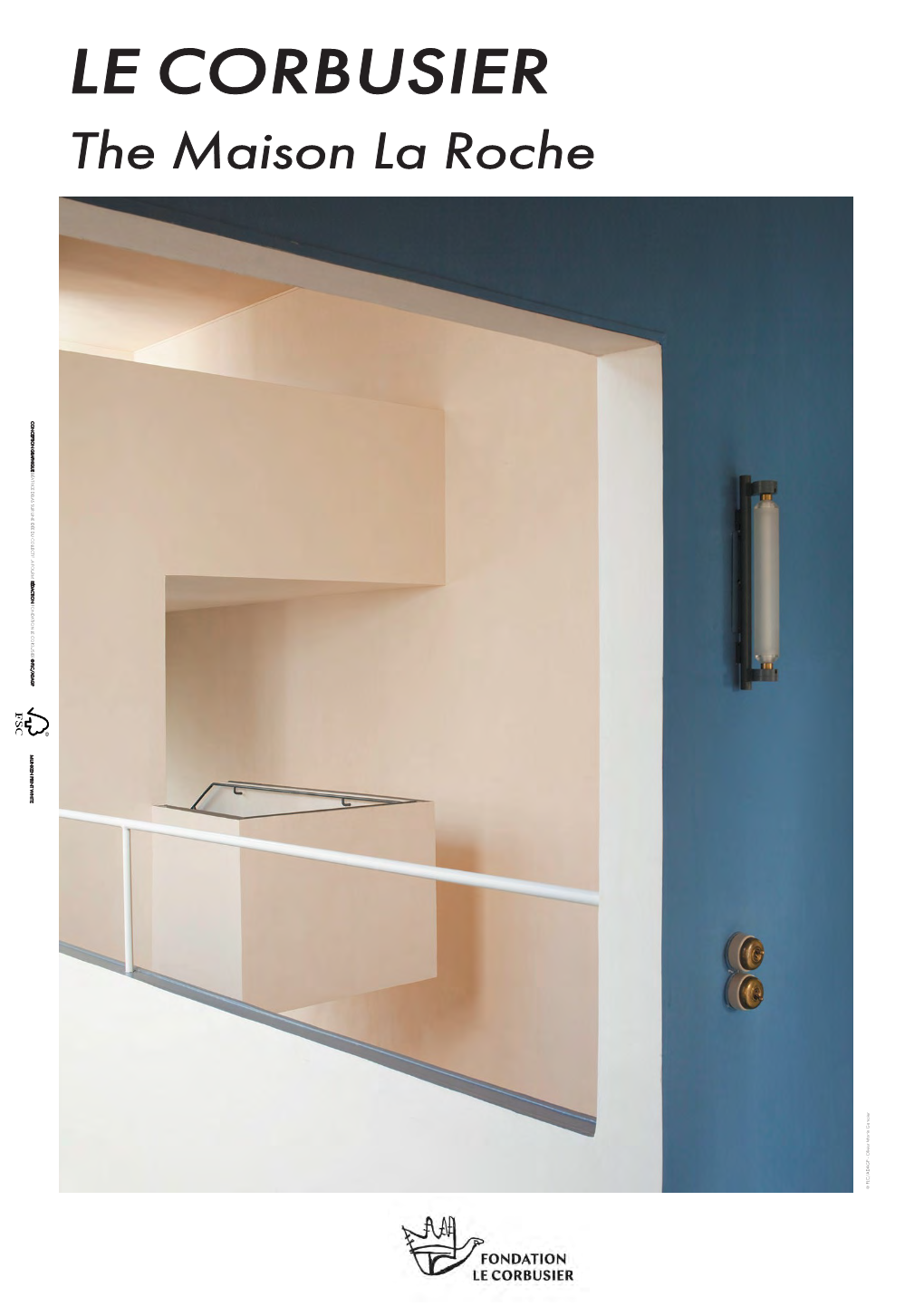

La Maison La Roche Construite Entre 1923 Et 1925 Par Le Corbusier Et Pierre Jeanneret, La Maison La Roche Constitue Un Projet Architectural Singulier

Dossier enseignant Maison La Roche – Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret. Photo Olivier Martin Gambier La Maison La Roche Construite entre 1923 et 1925 par Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret, la Maison La Roche constitue un projet architectural singulier. En effet, l’originalité de cette maison est de réunir une galerie de tableaux et les appartements du propriétaire et collectionneur : Raoul La Roche. La Maison La Roche est située au fond de l’impasse du Docteur Blanche dans le 16ème arrondissement de Paris, dans un quartier qui, à cette époque est en cours d’aménagement. L’utilisation de matériaux de construction nouveaux tels que le béton armé permet à Le Corbusier de mettre en œuvre ce qu’il nommera en 1927, les «Cinq points d’une architecture nouvelle». Il s’agit de la façade libre, du plan libre, des fenêtres en longueur, du toit-jardin, et des pilotis. La Maison La Roche représente un témoignage emblématique du Mouvement Moderne, précédant celui de la Villa Savoye (1928) à Poissy. De 1925 à 1933 de nombreux architectes, écrivains, artistes, et collectionneurs viennent visiter cette maison expérimentale, laissant trace de leur passage en signant le livre d’or disposé dans le hall. La Maison La Roche ainsi que la Maison Jeanneret mitoyenne ont été classées Monuments Historiques en 1996. Elles ont fait l’objet de plusieurs campagnes de restauration à partir de 1970. Maison La Roche 1 Le propriétaire et l’architecte THĖMES Le commanditaire : Le rôle de l’architecte Raoul La Roche (1889-1965) d’origine bâloise, (bâtir, aménager l’espace) s’installe à Paris en 1912 pour travailler au Crédit La commande en Commercial de France. -

The Minimum House Designs of Pioneer Modernists Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 2, Issue 2 – Pages 151-168 The Minimum House Designs of Pioneer Modernists Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand By Starlight Vattano Giorgia Gaeta† The article deals with the study of two projects of Eileen Gray, an architect who had turned her perception of reality into formal delicacy and Charlotte Perriand, who was able to promote the emphasis of collective and rational living. The article proposes the analysis of some unbuilt Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand’s projects designed in response to the social problems arising in 1936. Their projects of minimum temporary houses are a manifesto through which they investigates other principles of the Modern Movement with the variety of composition of small spaces in relation to the inside well-being at the human scale. The redrawing practice, shown in this article as methodological training to enrich knowledge about the historiography of these two pioneers of Modern Movement allows improving existing data of modern architecture and especially about unbuilt projects here deepened and explicated through new and unpublished drawings. Introduction The period here analysed is characterized by the important innovative laws of the 1920’s and 1930’s. Indeed the French government had given more rights to the work-class and, for the first time, also paid holidays. Several architectural competitions were organized for the realization of leisure projects or, at a building scale, of minimum weekend houses through which, the last innovative technologies were experimented. Among the most important figures who worked through rigorous and sophisticated survey methodologies, were Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand, two of the women pioneers of the Modern Movement, who presented their vision of minimum architecture for leisure and holidays. -

Charlotte Perriand the Modern Life

Charlotte Perriand The Modern Life Large Print Guide Charlotte Perriand is one of the great designers of the twentieth century. Her furniture designs have become enduring classics, and her harmonious approach to modern interiors remains influential. This is the first retrospective of her work in the UK for twenty-five years, and draws on the Charlotte Perriand Archives in Paris to shed new light on her creative process. Born in 1903, Perriand was already being noticed as a talented designer in her early twenties. Joining the studio of the modernist architect Le Corbusier, she developed the steel-tube furniture pieces that would long bear his name alone. Elegantly radical, they would become icons of modernism. But it was when she rejected that approach, and made her love of nature central to her work, that she found her unique voice. At the heart of Perriand’s nearly seventy-year career was a desire to balance contrasting elements: craftsmanship and industrial production, urban and rural, East and West. Influenced by the sense of space in traditional Japanese interiors, she sought that openness and flexibility in her own – qualities that came to define modern living. Perriand designed at every scale, from stools to ski resorts, but above all she strove to make good design accessible to as many people as possible. 2 The Machine Age ‘I called it my ball-bearing necklace, a symbol of my adherence to the twentieth-century machine age. I was proud that my jewellery didn’t rival that of the Queen of England.’ Charlotte Perriand caused a stir in 1927 when she exhibited her ‘Bar sous le toit’ (Bar under the roof), designed for her own apartment in Saint-Sulpice, Paris. -

Cité International Des Arts, Paris Helpful Hints

1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- +27 82 551 4853 ● [email protected] ● po box 14176 hatfield 0028 ● www.sanava.co.za Cité International Des Arts, Paris Helpful hints CONTENTS What you should know about Paris 3 1. Bookshops 3 2. Cité studio apartments 6 ● History 6 ● Inventory 8 ● Laundry 9 ● Neighbourhood 9 ● ● 3. Discount cards 10 ● ● 4. Do and See 11 ● Day trips 11 ● Night life 11 ● Maps 11 ● Museums 11 ● ● 5. Food 15 ● French food 15 ● Shopping for food 17 ● Where to eat 17 2 ● ● ● 6. Medical 18 ● ● 7. Public holidays in France 18 ● ● 8. South African embassy in Paris 19 ● ● 9. Shopping 19 ● Apartment stores 19 ● Markets 21 ● ● 10. Transport 22 ● Buses 22 ● Metro 23 ● Taxis 24 ● Driving 25 ● ● 11. Travel in France 26 ● Getting from Paris to other places 26 ● Airports 26 ● Railway stations 26 ● Tipping 29 12. Weather 29 3 What you should know about Paris (click to follow the links) Here are some travel tips from a local perspective – they’re things you might not think about on your own, and could help make your trip even easier. >> 30 Paris Travel Tips from a Local And beyond the physical layout of the city, it helps to know some basic visitor information, too – such as the country telephone code, the time zone, and the electricity. >> Paris Visitor Information Paris is a big city, so it pays to be looking at a city map when you’re planning your visit. But beyond that, the city is divided into districts called “arrondissements,” the numbers of which don’t always correspond exactly to the boundaries of the various neighbourhoods in Paris. -

LC35 MAISON DU BRESIL Family LC Year of Design 1959 Year of Production 2018

LC35 MAISON DU BRESIL Family LC Year of design 1959 Year of production 2018 A faithful reproduction of a student room in the Maison du Brésil, inaugurated in 1959 at the Cité Internationale of the University of Paris. In the early 1950s, the Brazilian government commissioned the design from the architect Lucio Costa, who in turn brought Le Corbusier on board, over time handing over more responsibility, to the point that the latter eventually signed off the building design. Le Corbusier’s office revised a number of key elements, and then brought in Charlotte Perriand to help with the interiors. The way Le Corbusier saw it, the wardrobe would separate the entrance hall and the bathroom block from the bedroom and study areas. Charlotte Perriand, on the other hand, took a more rationalist view, favouring the idea of having the wardrobe accessible from more than one side. For the bed frame, solid wood was preferred to metal, with a mattress and bolster. The apartment also included a wall-hung bookcase and blackboard, as well as the Tabouret Maison du Bresil, already available in Cassina Collection. Gallery Dimensions Designer Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, was born at La Chaux- de-Fonds, in the Swiss Jura, in 1887; he died in France, at Roquebrune- Cap-Martin, on the French Côte d’Azur, in 1965. Early in his career his work met with some resistance owing to its alleged «revolutionary» nature and the radical look it acquired from its «purist» experiments; in time , however, it won the recognition it deserved and it is still widely admired. -

Le Corbusier, Negotiating Modernity: Representing Algiers 1930-42

LE CORBUSIER, NEGOTIATING MODERNITY: REPRESENTING ALGIERS 1930-42 BY F. SHERRY McKAY B.A., University of British Columbia, 1974 M.A., Unversity of British Columbia, 1979 A THESIS SUMITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November, 1994 © F. Sherry McKay _______________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced shall make it degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library for extensive freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of (it2 The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date /ff/ DE-6 (2188) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Listofifiustrations iv Acknowledgement ix Introduction: “Everything is meaningful, nothingis meant” 1 Chapterone: ThePoetics ofPlace, thePragmaticsofPower 37 Chapter two: Defining Publics, Defining Problems: Plans Obus “A” & “B,” 193 1-1933 123 Chapter three: “Strategic Exemplars:” Plan Obus “C,,, 1934-1937 214 Chapter four: A Negotiated Truce: Plans Obus “D”, “E” and the Plan Directeur, 1938-1942 300 ifiustrations 358 Bibliography 398 II ABSTRACT The dissertation investigates the six plans devised by Le Corbusier for Algiers between 1930 and 1942, situating them within the representations given to the French presence in Algiers and their volatile political and cultural milieu.