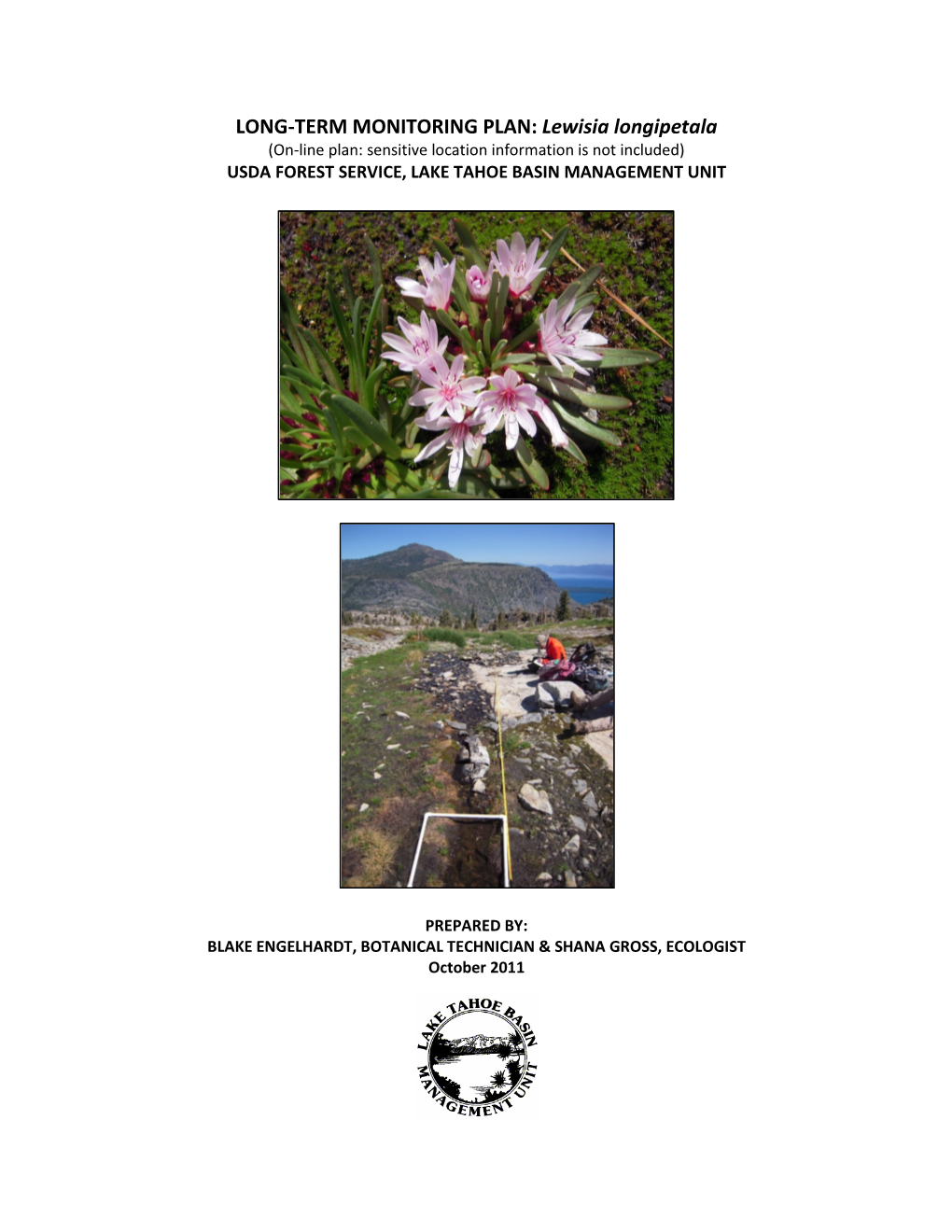

Lewisia Longipetala (On-Line Plan: Sensitive Location Information Is Not Included) USDA FOREST SERVICE, LAKE TAHOE BASIN MANAGEMENT UNIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reevaluating Late-Pleistocene and Holocene Active Faults in the Tahoe Basin, California-Nevada

CHAPTER 42 Reevaluating Late-Pleistocene and Holocene Active Faults in the Tahoe Basin, California-Nevada Graham Kent Nevada Seismological Laboratory, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, Nevada 89557-0174, USA Gretchen Schmauder Nevada Seismological Laboratory, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, Nevada 89557-0174, USA Now at: Geometrics, 2190 Fortune Drive, San Jose, California 95131, USA Jillian Maloney Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University, San Diego, California 92018, USA Neal Driscoll Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093, USA Annie Kell Nevada Seismological Laboratory, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, Nevada 89557-0174, USA Ken Smith Nevada Seismological Laboratory, University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, Nevada 89557-0174, USA Rob Baskin U.S. Geological Survey, West Valley City, Utah 84119, USA Gordon Seitz &DOLIRUQLD*HRORJLFDO6XUYH\0LGGOH¿HOG5RDG060HQOR3DUN California 94025, USA ABSTRACT the bare earth; the vertical accuracy of this dataset approaches 3.5 centimeters. The combined lateral A reevaluation of active faulting across the Tahoe and vertical resolution has rened the landward basin was conducted using a combination of air- identication of fault scarps associated with the borne LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) three major active fault zones in the Tahoe basin: imagery, high-resolution seismic CHIRP (acous- the West Tahoe–Dollar Point fault, Stateline–North tic variant, compressed high intensity radar pulse) Tahoe fault, and Incline Village fault. By using the proles, and multibeam bathymetric mapping. In airborne LiDAR dataset, we were able to identify August 2010, the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency previously unmapped fault segments throughout (TRPA) collected 941 square kilometers of airborne the Tahoe basin, which heretofore were difcult LiDAR data in the Tahoe basin. -

Landscaping with Native Plants by Stephen L

SHORT-SEASON, HIGH-ALTITUDE GARDENING BULLETIN 862 Landscaping with native plants by Stephen L. Love, Kathy Noble, Jo Ann Robbins, Bob Wilson, and Tony McCammon INTRODUCTION There are many reasons to consider a native plant landscape in Idaho’s short- season, high-altitude regions, including water savings, decreased mainte- nance, healthy and adapted plants, and a desire to create a local theme CONTENTS around your home. Most plants sold for landscaping are native to the eastern Introduction . 1 United States and the moist climates of Europe. They require acid soils, con- The concept of native . 3 stant moisture, and humid air to survive and remain attractive. Most also Landscaping Principles for Native Plant Gardens . 3 require a longer growing season than we have available in the harshest cli- Establishing Native Landscapes and Gardens . 4 mates of Idaho. Choosing to landscape with these unadapted plants means Designing a Dry High-Desert Landscape . 5 Designing a Modified High-Desert Landscape . 6 accepting the work and problems of constantly recreating a suitable artificial Designing a High-Elevation Mountain Landscape . 6 environment. Native plants will help create a landscape that is more “com- Designing a Northern Idaho Mountain/Valley fortable” in the climates and soils that surround us, and will reduce the Landscape . 8 resources necessary to maintain the landscape. Finding Sources of Native Plants . 21 The single major factor that influences Idaho’s short-season, high-altitude climates is limited summer moisture. Snow and rainfall are relatively abun- dant in the winter, but for 3 to 4 months beginning in June, we receive only a YOU ARE A SHORT-SEASON, few inches of rain. -

Biological Evaluation Sensitive Plants and Fungi Tahoe National Forest American River Ranger District Big Hope Fire Salvage and Restoration Project

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION SENSITIVE PLANTS AND FUNGI TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST AMERICAN RIVER RANGER DISTRICT BIG HOPE FIRE SALVAGE AND RESTORATION PROJECT Prepared by: KATHY VAN ZUUK Plant Ecologist/Botanist TNF Nonnative Invasive Plant Coordinator February 27, 2014 A Portion of the American Wildfire Area along Foresthill Divide Road 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Consultation to Date 6 Current Management Direction 8 Alternative Descriptions 9 Existing Environment 11 Description of Affected Sensitive Species Habitat Effects Analysis and 20 Determinations Reasonably Foreseeable Actions/Time Frames for the Analysis/ List of 20 Assumptions Effects to Species without potential habitat in the Project Area 22 • Lemmon’s milk-vetch, Astragalus lemmonii 22 • Modoc Plateau milk-vetch, Astragalus pulsiferae var. coronensis 22 • Sierra Valley Ivesia, Ivesia aperta var. aperta 22 • Dog Valley Ivesia, Ivesia aperta var. canina 23 • Plumas Ivesia, Ivesia sericoleuca 23 • Webber’s Ivesia, Ivesia webberi 23 • Wet-cliff Lewisia, Lewisia cantelovii 24 • Long-petaled Lewisia, Lewisia longipetala 24 • Follett’s mint, Monardella follettii 24 • Layne’s butterweed, Packera layneae 24 • White bark pine, Pinus albicaulis 25 • Sticky Pyrrocoma, Pyrrocoma lucida 25 Effects to Species with potential habitat in the Project Area 26 • Webber’s Milkvetch, Astragalus webberi 26 • Carson Range rock cress, Boechera rigidissima var. demota 27 • Triangle-lobe moonwort, Botrychium ascendens 27 • Scalloped moonwort, Botrychium crenulatum 27 • Common moonwort, Botrychium lunaria 27 • Mingan moonwort, Botrychium minganense 27 • Mountain moonwort, Botrychium montanum 28 • Bolander’s candle moss, Bruchia bolanderi 29 • Clustered Lady’s Slipper Orchid, Cypripedium fasciculatum 29 • Mountain Lady’s Slipper Orchid, Cypripedium montanum 30 • Starved Daisy, Erigeron miser 31 • Donner Pass Buckwheat, Eriogonum umbellatum var. -

Appendix C: Evaluation of Areas for Potential Wilderness

Appendices for the FEIS Appendix C: Evaluation of Areas for Potential Wilderness Introduction This document describes the process used to evaluate the wilderness potential of areas on the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit (LTBMU). The March 2009 inventory conducted according to Forest Service Handbook 1909.12, Chapter 70, 2007 is the basis for this evaluation. The LTBMU was evaluated to determine landscape areas that exhibited inherent basic wilderness qualities such the degree of naturalness and undeveloped character. In addition to the wilderness qualities an area might possess, the area must also provide opportunities and experiences that are dependent on and enhanced by a wilderness environment and area boundaries that could be managed as wilderness. It was determined that areas adjacent to existing wilderness and existing Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs) were areas were most likely to have the characteristics described above. Other areas around the basin exhibited some of the required characteristics but not enough to be qualified for a congressional wilderness designation. Six areas were identified and evaluated. The analysis is based on GIS mapping of existing wilderness and inventoried roadless area polygon data, adjusted based on local knowledge. Three tests were used—capability, availability, and need—to determine suitability as described in Forest Service Handbook 1909.12, Chapter 70, 2007. In addition to the inherent wilderness qualities an area might possess, the area must provide opportunities and experiences that are dependent on and enhanced by a wilderness environment. The area and boundaries must allow the area to be managed as wilderness. Capability is defined as the degree to which the area contains the basic characteristics that make it suitable for wilderness designation without regard to its availability for or need as wilderness. -

FREMONTIA a Journal of the California Native Plant Society FREMONTIA Vol

Vol. 25, No. 1 January 1997 FREMONTIA A Journal of the California Native Plant Society FREMONTIA Vol. 25 No. 1 January 1997 Copyright © 1997 California Native Plant Society Phyllis M. Faber, Editor • Laurence J. Hyraan, Art Director • Beth Hansen, Designer California Native Plant Society Dedicated to the Preservation of the California Native Flora The California Native Plant Society is an organization of lay educational work includes: publication of a quarterly journal, men and professionals united by an interest in the plants of Cali Fremontia, and a quarterly Bulletin which gives news and fornia. It is open to all. Its principal aims are to preserve the native announcements of Society events and conservation issues. flora and to add to the knowledge of members and the public at Chapters hold meetings, field trips, plant and poster sales. Non- large. It seeks to accomplish the former goal in a number of ways: members are welcome to attend. by monitoring rare and endangered plants throughout the state; by The work of the Society is done mostly by volunteers. Money acting to save endangered areas through publicity, persuasion, and is provided by the dues of members and by funds raised by on occasion, legal action; by providing expert testimony to chapter plant and poster sales. Additional donations, bequests, government bodies; and by supporting financially and otherwise and memorial gifts from friends of the Society can assist greatly the establishment of native plant preserves. Much of this work is in carrying forward the work of the Society. Dues and donations done through CNPS Chapters throughout the state. -

Perspectives from Montiaceae (Portulacineae) Evolution. II

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 2 October 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0566.v1 Hershkovitz Montiaceae Ecological Evolution 1 Perspectives from Montiaceae (Portulacineae) evolution. II. Ecological evolution, phylogenetic comparative 2 analysis, and the Principle of Evolutionary Idiosyncraticity 3 4 5 Mark A. Hershkovitz1 6 1Santiago, Chile 7 [email protected] 8 9 10 ABSTRACT 11 12 The present paper reviews evidence for ecological evolution of Montiaceae. Montiaceae 13 (Portulacineae) comprise a family of ca. 275 species and ca. 25 subspecific taxa of flowering plants 14 distributed mainly in extreme western America, with additional endemism elsewhere, including other 15 continents and islands. They have diversified repeatedly across steep ecological gradients. Based on narrative 16 analysis, I argue that phylogenetic transitions from annual to perennial life history have been more frequent 17 than suggested by computational phylogenetic reconstructions. I suggest that a reported phylogenetic 18 correlation between the evolution of life history and temperature niche is coincidental and not causal. I 19 demonstrate how statistical phylogenetic comparative analysis (PhCA) missed evidence for marked moisture 20 niche diversification among Montiaceae. I discount PhCA evidence for the relation between Montiaceae 21 genome duplication and ecological diversification. Based on the present analysis of Montiaceae evolution, I 22 criticize the premise of the prevalent statistical approach to PhCA, which tests Darwinian -

![Scientific [Common] Lewisia Sacajaweana – BL Wilson & E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6996/scientific-common-lewisia-sacajaweana-bl-wilson-e-2696996.webp)

Scientific [Common] Lewisia Sacajaweana – BL Wilson & E

SPECIES: Scientific [common] Lewisia sacajaweana – B. L. Wilson & E. Rey- Vizgirdas [Sacajawea’s Bitter-Root] Forest: Salmon–Challis National Forest Forest Reviewer: Brittni Brown; John Proctor Date of Review: 15 February 2018; 13 March 2018 Forest concurrence (or YES recommendation if new) for inclusion of species on list of potential SCC: (Enter Yes or No) FOREST REVIEW RESULTS: 1. The Forest concurs or recommends the species for inclusion on the list of potential SCC: Yes_X__ No___ 2. Rationale for not concurring is based on (check all that apply): Species is not native to the plan area _______ Species is not known to occur in the plan area _______ Species persistence in the plan area is not of substantial concern _______ FOREST REVIEW INFORMATION: 1. Is the Species Native to the Plan Area? Yes _X_ No___ If no, provide explanation and stop assessment. 2. Is the Species Known to Occur within the Planning Area? Yes _X _ No___ If no, stop assessment. Table 1. All Known Occurrences, Years, and Frequency within the Planning Area Year Number of Location of Observations (USFS Source of Information Observed Individuals District, Town, River, Road Intersection, HUC, etc.) July 31, 267 total North Fork Ranger District IDFG Element Occurrence EO 1990 individuals Bighorn Crags, along the Crags Number: 4 (4 Trail (FS Trail 021) on divide EO_ID: 26536 populations) between Roaring Creek and Old EO_ID: 4417 Clear Creek Xeric crest, all aspects, 0-8 percent slope, open whitebark pine woodland, 8,900 feet in elevation. July 31, 53 total North Fork Ranger District IDFG Element Occurrence EO 1990 individuals Along the Crags Trail (FS Trail Number: 5 021) about 1 mile south of Year Number of Location of Observations (USFS Source of Information Observed Individuals District, Town, River, Road Intersection, HUC, etc.) (3 Cathedral Rock and 2.7 miles EO_ID: 26519 populations) NW of Crags Campground Old EO_ID: 1714 Xeric crest, all aspects, 0-3 percent slope, open whitebark pine woodland, 8,800 feet in elevation. -

FOOD PLANTS of the NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS by ELIAS YANOVSKY, Chemist, Carbohydrate Resea'rch Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils

r I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Miscellaneous Publication No. 237 Washington, D. C. July 1936 FOOD PLANTS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS By KLIAS YANOYSKY Chemist Carbohydrate Research Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils Foe sale by the Superintendent of Dosnenia, Washington. D. C. Price 10 centS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 237 WASHINGTON, D. C. JULY 1936 FOOD PLANTS OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS By ELIAS YANOVSKY, chemist, Carbohydrate Resea'rch Division, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils CONTENTS Page Page Foreword 1 Literature cited 65 Introduction I Index 69 Plants 2 FOREWORD This publication is a summary of the records of food plants used by the Indians of the United States and Canada which have appeared in ethnobotanical publications during a period of nearly 80 years.This compilation, for which all accessible literature has been searched, was drawn up as a preliminary to work by the Bureau of Chemistry and Soils on the chemical constituents and food value of native North American plants.In a compilation of this sort, in which it is im- possible to authenticate most of the botanical identifications because of the unavailability of the specimens on which they were based, occa- sional errors are unavoidable.All the botanical names given have been reviewed in the light of our present knowledge of plant distribu- tion, however, and it is believed that obvious errors of identification have been eliminated. The list finds its justification as a convenient summary of the extensive literature and is to be used subject to con- firmation and correction.In every instance brief references are made to the original authorities for the information cited. -

Lewisia Columbiana (Columbia Lewisia) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling

Lewisia columbiana (Columbia Lewisia) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling Distribution Status: Present State Rank: S1S2 (Species of Concern) Global Rank: G4G5 Modeling Overview Data Source Last Updated: April 26, 2018 Model Produced On: June 11, 2021 Deductive Modeling Modeling Process, Outputs, and Suggested Uses This is a simple rule-based model using species occurrences delineated for vascular and non-vascular plant species. These species could not be modeled with inductive methods, either due to limited observations or spatial extent or because an inductive model had poor performance. Species occurrences are discretely mapped polygons where the species has been documented. Plant species occurrence polygons are delineated by the MTNHP Botanist, and can be generated in two ways: 1) Polygons are hand-mapped and scaled to aggregate neighboring observation points and their adjacent habitat, while trying to exclude barriers, reduce known unoccupied habitat, and ignore management boundaries, or 2) Circular polygons are automatically generated by buffering the single observation point by its location uncertainty distance. For compatibility with other predictive distribution models the Montana Natural Heritage Program produces, we have intersected these species occurrences with a uniform grid of hexagons that have been used for planning efforts across the western United States (e.g. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies - Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool). Each hexagon is one square mile in area and approximately one kilometer in length on each side. Any hexagon that intersected a species occurrence was classified as suitable habitat. Model outputs are not evaluated and we suggest they be used to generate potential lists of species that may occupy lands within each hexagon for the purposes of landscape-level planning. -

Lewisia Rediviva Bitterroot

Lewisia rediviva Bitterroot by Kathy Lloyd and Spencer Shropshire Montana Native Plant Society Photo: Drake Barton Lewisia rediviva (Bitterroot) he Corps of Discovery left the Pacific ple and trade commodity. A bag of bitterroot could coast in the spring of 1806 for their jour- be traded for a horse, and the noise of women ney home. By late June they were crossing pounding bisquit-root reminded Clark of “a nail fac- the Rocky Mountains at Lolo Pass in deep tory.” The Flathead and neighboring tribes assem- Tsnow, attempting to retrace their earlier route. In bled every spring in the Bitterroot Valley to harvest late evening on the last day in June they reached the plants. May was known as “bitterroot month,” a Traveler’s Rest, where they had camped on the west- time before flowering when the roots had maximal bound journey, in the vicinity of present-day Lolo, starch content, and a woman with a sharp stick could Montana, near the confluence of Lolo Creek and the dig a pound in three days. As its name implies, for Bitterroot River. During the descent Lewis and his some the taste was unsavory. Lewis found them horse had fallen 40 feet down a steep slope. He was “naucious to my pallate,” and Montana pioneer miraculously unhurt and on July 1 or 2 he collected Granville Stuart said he “could never eat it unless several floral specimens, among them six bitterroot very hungry,” though he added, “many of the moun- plants, which are preserved in the Lewis & Clark taineers are very fond of it.” Herbarium in Philadelphia. -

Lewisia Rediviva (Bitterroot) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling

Lewisia rediviva (Bitterroot) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling Distribution Status: Present State Rank: S4S5 Global Rank: G5 Modeling Overview Created by: Braden Burkholder Creation Date: May 20, 2021 Evaluator: Scott Mincemoyer Evaluation Date: May 25, 2021 Inductive Model Goal: To predict the current distribution and relative suitability of general habitat for Lewisia rediviva at large spatial scales across its presumed current range in Montana. Inductive Model Performance: The model appears to adequately reflect the current distribution and relative suitability of general habitat for Lewisia rediviva at larger spatial scales across its presumed current range in Montana. Evaluation metrics indicate an acceptable model fit and the delineation of habitat suitability classes is well supported by the data. Overall, the model performs relatively well across the species’ range although it does miss some smaller areas of localized habitat especially at the hexagon scale. Optimal habitat is poorly represented at the hexagon scale. Model would likely benefit from additional, current and precisely-loccated observation data . The model is presented as a reference, but more observation records, site-specific data, and/or other environmental layers may be needed to improve performance. Inductive Model Output: http://mtnhp.org/models/files/Lewisia_rediviva_PDPOR040D0_20210520_modelHex.lpk Suggested Citation: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 2021. Lewisia rediviva (Bitterroot) predicted suitable habitat model created on May 20, 2021. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT. 17 pp. Montana Field Guide Species Account: http://fieldguide.mt.gov/speciesDetail.aspx?elcode=PDPOR040D0 Species Model Page: http://mtnhp.org/models/?elcode=PDPOR040D0 page 1 of 17 Lewisia rediviva (Bitterroot) Predicted Suitable Habitat Modeling May 20, 2021 Inductive Modeling Model Limitations and Suggested Uses This model is based on statewide biotic and abiotic environmental layers originally mapped at a variety of spatial scales and standardized to 90×90-meter raster pixels. -

Calochortus Kennedyi Our Cover Is a Painting by Carolyn Crawford of Arvada, Colorado

Bulletin of the American Rock Garden Society Volume 48 Number 1 Winter 1990 Cover: Calochortus kennedyi Our cover is a painting by Carolyn Crawford of Arvada, Colorado. A photograph by Stan Farwig served as her model. Bulletin of the American Rock Garden Society Volume 48 Number 1 Winter 1990 Contents Wildflower Haunts of California, by Wayne Roderick 3 Lewisias of the Sierra Nevada, by B. LeRoy Davidson 13 Eriogonums to Grow and Treasure, by Margaret Williams 21 Calochortus-. Why Not Try Them? by Boyd Kline 25 California Rock Ferns, by Margery Edgren 31 Plant Gems from the Golden State, by John Andrews 35 Lewisias Wild and in Cultivation, by Sean Hogan 47 Pacific Coast Iris, by Lewis and Adele Lawyer 53 Diplacus for Rock Gardens, by David Verity 65 Identifying California Alpines, by Wilma Follette 66 '<ctns 2 Bulletin of the American Rock Garden Society Vol. 48(1) Wildflower Haunts of California by Wayne Roderick In California there is so much plants must produce a long tap-root diversity in climate and topography to survive the dry period, and this in that it takes nearly a lifetime to see all turn means nearly certain death to our interesting plants. For those who any plant dug. So remember, I shall have a few weeks to explore there bring the wrath of California down on are many places to visit. If you are your head for digging any plant! But here in July, it is too late in the year California will bless you for taking a to visit the deserts, to see fields of the little seed.