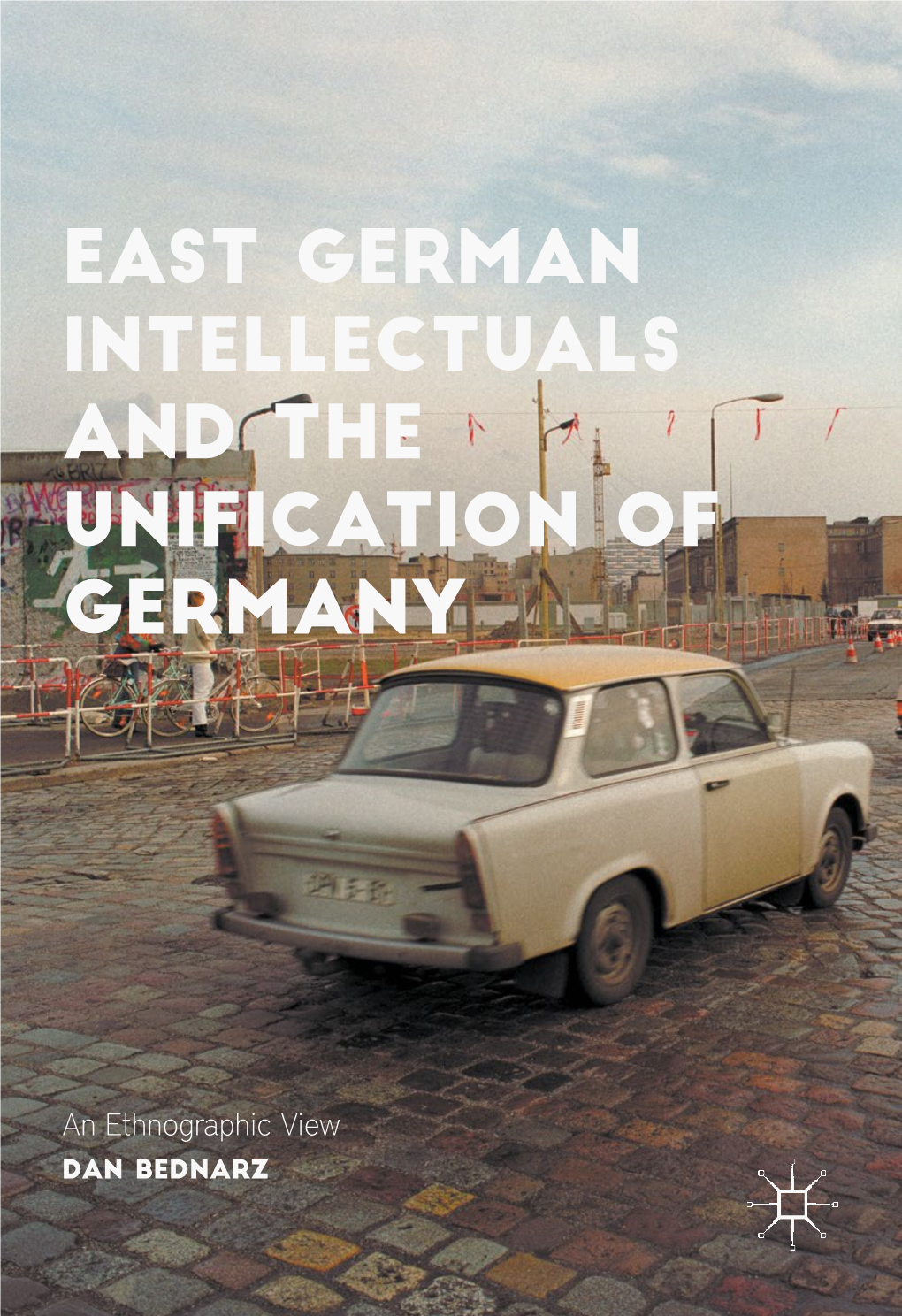

East German Intellectuals and the Unification of Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath Berlin

Beneath Berlin. A Beginner’sB GuideB to the German Capital. 1 Section key. -Sights and Monuments- Symbol key. Contents. About Berlin. -Art and Museums- -Editor’s Crown- Neighbourhoods > pp. 7-11 This symbol indicates that our crack teams of eaters, Berlin Timeline > pp. 12-15 -Outdoors- drinkers, party goers and art critics have chosen the Survival Guide > pp. 16-23 crowned article as truly the best of Berlin. -Food and drink- Language Tips > pp. 24-25 Beers of Berlin > pp. 26-27 -Nightlife- -Bargain Birdsong- This symbol indicates Ampelmann > pp. 28-29 when something is best for a budget without Getting Around > pp. 30-33 -Shopping- compromising on quality - it essentially appears when good things are going cheap. A t t r a c t i o n R e v i e w s . -Entertainment- Sights and Monuments > pp. 34-58 -Accommodation- Art and Museums > pp. 59-83 Outdoors > pp. 84-104 Food and Drink > pp. 105-132 Nightlife > pp. 133-145 Shopping > pp. 146-155 Entertainment > pp. 156-163 Accommodation > pp. 164-171 4 52 Ampelmann: Who is he? Remember the traffic man you Hackescher Markt, Pots- see when you cross the street? damer Platz, Karl Liebkne- Have you ever wondered if it cht Straße, Gendarmenmarkt was more than a stop/go sign? and Unter den Linden. For Different countries have varied those with a sweet-tooth, versions of what Berliners call complimentary Ampelmann the “Ampelmännchen”. If you gummy sweets are available ever get lost, just look at the traf- in every store so feel free to fic lights. -

Ost-Ampelmännchen and the Memory of The

Crossing Past and Present: Ost-Ampelmännchen and the Memory of the German Democratic Republic By: Kyle Massia A thesis submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. April, 2014, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright by Kyle Massia, 2014 Dr. Kirrily Freeman Associate Professor Dr. Nicole Neatby Associate Professor Dr. John Munro Assistant Professor Dr. John Bingham Assistant Professor Date: 22 April 2014 1 Abstract Crossing Past and Present: Ost-Ampelmännchen and the Memory of the German Democratic Republic By Kyle Massia, 22 April 2014 Abstract: Despite his connection to daily life in East Germany; east Germans began replacing their chubby, hat-wearing pedestrian light figure (the Ost-Ampelmännchen, or Ampelmann) with the non-descript West German one in the euphoria of reunification. By the mid-1990s, however, east Germans began to see their old state differently, bringing back their Ampelmann as a reminder of the safety, security, and equality their old state possessed. Following his resurrection, Ampelmann transformed into a pop-culture icon as shops sprung up selling Ampelmann-branded products. From here, his popularity spread as Ampelmann lights appeared in western Germany and Ampelmann shops opened their doors not only in Berlin, but also in Tokyo and Seoul. East Germans supported this, declaring that his popularity showed that their past and its values could find a place in a globalizing world. In doing so, East Germans have used and rewritten their past to promote a more respectful and equitable alternative to modern life. 2 Introduction: Traffic lights were probably the last thing on the minds of East Germans on 9 November 1989 as the Berlin Wall fell and the borders of their German Democratic Republic (GDR) opened. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON RESTRICTED Spec(92)14 4 September 1992 TARIFFS AND TRADE Working Party-on German Unification - Transitional'. Measures Adopted by the European Communities COMPILATION OF INFORMATION RECEIVED BY THE WORKING PARTY This document compiles all information received to date by the Working Party, including the questions and answers in Spec(91)10 and Spec(91)85, the report by the European Communities in L/6974 and questions and answers received since the last meeting of the Working Party. In order to facilitate the Working Party's assessment of this information, it has been sorted by topic, as listed below. Cross-references have been rectified to correspond with this document. The text of the report appears first in each section, followed by the questions and answers. Page I. General 2 II. Implementation of Transitional Tariff Provisions 6 2.1 Origin rules and processing requirements 12 2.2 Market access 15 2.3 Utilization of transitional measures 23 III. Implementation of Transitional Standards Provisions 26 IV. Trade Agreements between the Former German Democratic Republic and Third Countries 37 V. Trade in Non-Agricultural Products 46 5.1 Coal and metals 46 5.2 Textiles 49 VI. Agricultural Products 50 VII. Other Issues 68 92-1229 Spec(92)14 Page 2 I. GENERAL (From L/6794) At their Forty-Sixth Session in December 1990, the CONTRACTING PARTIES decided to grant a waiver for transitional measures adopted by the European Communities on German Unification (L/6792). That decision required, inter alia, that the European Communities submit a report in December 1991 on the use that has been made of this waiver. -

Forest Policy Analysis

FORESTPOLICY ANALYSIS FOREST POLICY ANALYSIS by MAX KROTT Institute for Forest Policy and Nature Conservation, Göttingen, Germany Translated by Renée von Paschen EUROPEAN FOREST INSTITUTE A C.I.P. Catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 1-4020-3478-4 (HB) ISBN 978-1-4020-3478-7 (HB) ISBN 1-4020-3485-7 (e-book) ISBN 978-1-4020-3485-5 (e-book) Published by Springer, P.O. Box 17, 3300 AA Dordrecht, The Netherlands. www.springeronline.com Cover picture by Achim Dohrenbusch, Göttingen, Germany Printed on acid-free paper Title of the original German edition: Krott, Politikfeldanalyse Forstwirtschaft, 1st edition © 2001 by Parey Buchverlag im Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag GmbH, Berlin All Rights Reserved © 2005 Springer No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed in the Netherlands. FOREWORD Although forest policy is an established course in most European university forestry curricula, apart from a special predilection of the teacher, its content varies from country to country according to the position of the forest sector in the domestic economy and society. In some countries, forestry is the backbone of a strong wood-processing industry, in others, recreational uses and amenity values of forests dominate. Despite these differences, all countries have in common the fact that the diversity of interests in forests has increased. -

Dr. Christine Schmid

Dr. Christine Schmid Vollständige Publikationsliste Monografien, Sammelbände Schmid, Christine (in Vorb.) Die Übereinstimmung politischer Orientierungen und Verhaltensbereitschaf- ten in jugendlichen Freundschaften: Selektion oder Sozialisation? [für Jahrbuch Jugendforschung 2006.] Schmid, Christine (in Vorb.) Die Sozialisation von sozialem und politischem Engagement im Elternhaus und in der Gleichaltrigenwelt. In: Schuster, Beate H.; Kuhn, Hans-Peter; Uhlendorff, Harald (Hrsg.): Entwicklung in sozialen Beziehungen – Heranwachsende in ihrer Auseinandersetzung mit Familie, Freunden und Gesellschaft. Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius. Schmid, Christine; Oswald, Hans (in Vorb.) Der Einfluss von Eltern und Freunden auf die Ausländer- feindlichkeit von Gymnasiasten in einem neuen Bundesland. [erscheint im Kongressband des 32. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie, Campus-Verlag]. Oswald, Hans; Schmid, Christine (in Vorb.) The influence of parents and peers on political participation of adolescents in the new states of Germany. In: Hofer, Manfred, Sliwka, Anne; Diedrich, Martina (Hrsg.): Citizenship education in youth – theory, research, and practice. Münster, New York: Waxmann. Schmid, Christine (2004) Politisches Interesse von Jugendlichen. Eine Längsschnittuntersuchung zum Einfluss von Eltern, Gleichaltrigen, Massenmedien und Schulunterricht. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag. Kuhn, Hans-Peter; Schmid, Christine (2004) Politisches Interesse, Mediennutzung und Geschlechterdiffe- renz. Zwei Thesen zur Erklärung von Geschlechtsunterschieden -

17 April 2016

12 – 17 APRIL 2016 FESTIVAL CATALOGUE INHALT CONTENTS VORSPANN INTRO Programmplan Programme Schedule ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Tickets ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Impressum Imprint ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Grußworte Welcoming Addresses ..................................................................................................................................................................................6 Partner & Förderer Partners & Supporters ..............................................................................................................................................................10 Team ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Preise & Preisstifter Awards & Sponsors ...................................................................................................................................................................12 -

Soul: Diorama

SOUL: DIORAMA ____________ A Master’s Exhibition of Sculpture Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Art ____________ by © Ryan Skylar Gibbons 2017 Fall 2017 SOUL: DIORAMA A Master’s Exhibition by Ryan Skylar Gibbons Fall 2017 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: _________________________________ Sharon Barrios, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A. Cameron G. Crawford, M.F.A., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Sheri Simons, M.F.A. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this project may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights....................................................................................................... iii List of Figures............................................................................................................. v Abstract....................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER I. Introduction............................................................................................... 1 Limitations .................................................................................... 3 Definitions.................................................................................... -

Berlin: Stalins

Berlin: Stalins öra C-J CHARPENTIER FRANKFURTER ALLEE, som bytt namn flera gånger och bland annat hetat Stalin- allee, skär genom östra Berlin fram till Alexanderplatz – en gata präglad judisk köpenskap, blodiga uppror, krigets bomber, massmord och storskaliga arkitektoniska experi- ment. Följt av hämningslös mark- nadsekonomi efter Murens fall BERLIN: STALINS ÖRA är en unik dokumentation av gatans historia, kulturliv och politiska växlingar från gårdag till samtid – en spännande och i högsta grad läsvärd skildring signerad antro- pologen C-J Charpentier. C-J CHARPENTIER Berlin: Stalins öra Berättelser från en gata Stalins öra Omslagsbilden – Walter Womackas hyllning till lärare och utbildning, Haus des Lehrers, Karl-Marx-Allee © C-J Charpentier (2014) Foto: C-J Charpentier Förlag: Läs en bok Anträde Den här boken handlar om en vandring genom östra Berlin en tidig höstdag 2013, från Alt-Friedrichsfelde till Alexanderplatz längs den klassiska Frankfurter Allee, som en gång hette Stalin- allee och som sedan 1961 åter heter Frankfurter Allee i öster, medan den västra delen gavs namnet Karl-Marx-Allee. Det är en fantastisk gata, måhända den mest händelsemättade i Europa, ett stråk där brutal politik möter arkitektur, konst och litteratur. Men också en ”småfolkets inköpsboulevard” ‒ från sent 1800-tal till andra världskrigets bomber. Jag har varit i Berlin ungefär sextio gånger: före muren, under murtiden, natten då muren föll, och under de hittillsvarande åren som återförenad huvudstad. Som antropolog fascineras jag särskilt av den östra halvan, eftersom den – efter die Wende ‒ exemplifierar ett politiskt och ekonomiskt systemskifte, som på olika sätt präglat både människor och stadslandskap; något som jag länge tänkt dokumentera och skriva om. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Klepper, Gernot; Michaelis, Peter Working Paper — Digitized Version Will the Dual System manage packaging waste? Kiel Working Paper, No. 503 Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Klepper, Gernot; Michaelis, Peter (1992) : Will the Dual System manage packaging waste?, Kiel Working Paper, No. 503, Kiel Institute of World Economics (IfW), Kiel This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/597 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Kieler Arbeitspapiere Kiel Working Papers Kiel Working Paper No. 503 Will the 'Dual System' Manage Packaging Waste? Gernot klepper and Peter Michaelis January 1992 Institut fiir Weltwirtschaft an der Universitat Kiel The Kiel Institute of World Economics ISSN 0342-0787 Kiel Institute of World Economics Dusternbrooker Weg 120 D-2300 Kiel 1, FRG Kiel Working Paper No. -

Inter Nos VOLUME 52, NO

inter nos VOLUME 52, NO. 2 PUBLISHER Allen Henderson From the Independent Teacher Associate Editor Executive Director [email protected] Looking Both Ways and Crossing at The Light MANAGING EDITOR (Or How I Fell in Love with Traffic Light Man) Deborah Guess ne of the unexpected delights of Director of Operations the Summer 2019 Inaugural NATS [email protected] O Transatlantic Vocal Pedagogy Exchange DESIGNER Trip to Germany was the discovery of Paul Witkowski East Germany’s iconic Ampelmann (traffic Marketing and Communications Manager light man). Ampelmann (also known as [email protected] the diminutive Ampelmänchen—little traffic light man) was designed in 1961 INDEPENDENT TEACHER ASSOCIATE EDITOR by traffic psychologist (yes, that’s a Cynthia Vaughn career) Karl Peglau to have different [email protected] shapes so that pedestrians with red/green color blindness could safely cross roads. inter nos is the official newsletter of the National Association of Teachers of The plump body of Ampelmann meant Singing. It is published two times per year more light would shine through for (spring and fall) for all NATS members. greater visibility. From the first taxi ride from the East Berlin train station to our hotel I spotted PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO: Cynthia Vaughn the rotund jaunty little walking man with a hat urging Associate Editor NATS pedestrians to “Go! Go! Go!”. I quickly discovered that for Inter Nos Phone: 904.992.9101 [email protected] Fax: 904.262.2587 Ampelmann was everywhere—on T-shirts, backpacks, and Email: [email protected] water bottles, in Ampelmann souvenir shops, and four- Visit us online at: www.nats.org foot-tall green Ampelmännchen on corners and squares. -

Embedding Sustainability Into a Branded Design Company

The Green Light towards Sustainability: Embedding Sustainability into a Branded Design Company Reed Evans, Ricardo García Guerra, Myriam Schaefer, Isabella Wagner School of Engineering, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2011 Thesis submitted for completion of the Master in Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability at Blekinge Institute of Technology Abstract: Production and consumption of products contribute to the global sustainability challenge by degrading natural and social systems. This thesis focuses on branded products, which through powerful images and meanings symbolise the core business of a company and a platform of identification for its stakeholders. This study investigates the possibility to align a brand and its company with sustainability. With the help of a small branded design company in Berlin, which served as case study, a strategic management planning process was conducted and action research was used to be able to engage the participants in creating movement towards sustainability. The research shows that there are major internal and external barriers and motivations that can either hinder or inspire. The actions and approaches that were identified for a branded design company represent possible means to transform its business towards sustainability. Natural resources are decreasing relative to the growth in human population and affluence. This fuels the need to develop more sustainable products so that human needs and natural eco-systems can thrive. A branded design company has the ability to help lead society through innovating products, services, and activities towards a sustainable future. Keywords: Strategic Sustainable Development, Systems Thinking, Strategic Management Planning, Brand, Sustainable Product Design, Innovation for Sustainability Statement of Contribution This thesis was developed and written as a collaborative effort. -

Can Gerhard Schröder Do It? Prospects for Fundamental Reform of the German Economy and a Return to High Employment

IZA DP No. 1059 Can Gerhard Schröder Do It? Prospects for Fundamental Reform of the German Economy and a Return to High Employment Irwin Collier DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER March 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Can Gerhard Schröder Do It? Prospects for Fundamental Reform of the German Economy and a Return to High Employment Irwin Collier Free University of Berlin and IZA Bonn Discussion Paper No. 1059 March 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available on the IZA website (www.iza.org) or directly from the author.