LOUISIANA Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Stylistic Study of Figurative Language in Katy Perry's

A STYLISTIC STUDY OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE IN KATY PERRY’S SONG LYRICS FROM WITNESS ALBUM A Thesis Submitted to Faculty of Adab and Humanities In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Strata One Alfi Syahrina NIM. 11150260000086 ENGLISH LITERATURE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2019 ABSTRACT Alfi Syahrina, A Stylistic Study of Figurative Language in Katy Perry’s Song Lyrics from Witness Album. Thesis: English Literature Department, Faculty of Adab and Humanities, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, 2019. This research is aimed at taking comprehensive understanding regarding the type of figurative language within the song lyrics in Katy Perry’s Witness (2017) album to know what her perspectives about her country (USA) especially after the 2016 election. After understanding the type of figurative language, it is then related and connected to the idea of the author. The utilized theories in this research are stylistics by Geoffrey Leech and Mick Short and figurative language by Laurence Perrine. This study uses qualitative method and content analysis approach since the object of the analysis is formed as song lyrics. Adopting the Perrine’s theory of figurative language, it is discovered that there are only seven of twelve types of figurative language i.e. simile, metaphor, personification, metonymy, symbol, hyperbole, and irony. Metaphor mostly dominates in the song lyrics with its total eight times (29,63%) of occurrence. After finding the type of figurative language, the researcher relates the meaning of figurative language to the context in the data. Hence, it is discovered that the author’s political perspective and women empowerment in metaphor which dominates the type of figurative language. -

“Folk Music in the Melting Pot” at the Sheldon Concert Hall

Education Program Handbook for Teachers WELCOME We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Sheldon Concert Hall for one of our Education Programs. We hope that the perfect acoustics and intimacy of the hall will make this an important and memorable experience. ARRIVAL AND PARKING We urge you to arrive at The Sheldon Concert Hall 15 to 30 minutes prior to the program. This will allow you to be seated in time for the performance and will allow a little extra time in case you encounter traffic on the way. Seating will be on a first come-first serve basis as schools arrive. To accommodate school schedules, we will start on time. The Sheldon is located at 3648 Washington Boulevard, just around the corner from the Fox Theatre. Parking is free for school buses and cars and will be available on Washington near The Sheldon. Please enter by the steps leading up to the concert hall front door. If you have a disabled student, please call The Sheldon (314-533-9900) to make arrangement to use our street level entrance and elevator to the concert hall. CONCERT MANNERS Please coach your students on good concert manners before coming to The Sheldon Concert Hall. Good audiences love to listen to music and they love to show their appreciation with applause, usually at the end of an entire piece and occasionally after a good solo by one of the musicians. Urge your students to take in and enjoy the great music being performed. Food and drink are prohibited in The Sheldon Concert Hall. -

Escape from Wonderland - a Novel Crystal Denise Pennymon University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2018-01-01 Escape From Wonderland - A Novel Crystal Denise Pennymon University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Pennymon, Crystal Denise, "Escape From Wonderland - A Novel" (2018). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1511. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1511 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESCAPE FROM WONDERLAND - A NOVEL - CRYSTAL DENISE PENNYMON Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: Tim Hernandez, M.F.A., Chair Elizabeth Sheid, M.F.A. Jose De Pierola, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Dedication To my grandmother, Annie Lois Price Pennymon June 3, 1927 – October 29, 2015 To my aunt, Janice Maria Pennymon Morgan March 17, 1958 – September 3, 2016 To my baby brother, Jonathan Dennard Pennymon May 9, 1985 – July 13, 2017 ESCAPE FROM WONDERLAND -A NOVEL- by CRYSTAL DENISE PENNYMON, B.S. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Liberal Arts The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2018 Acknowledgements In remembrance of my grandmother, Annie Lois Pennymon (1927-2015), who said that I told little lies all the way from Georgia to Kentucky while sitting on the arm rest of her Oldsmobile Toronado at 3-years-old. -

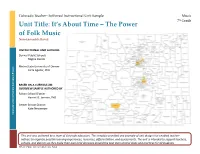

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

Southeast Texas: Reviews Gregg Andrews Hothouse of Zydeco Gary Hartman Roger Wood

et al.: Contents Letter from the Director As the Institute for riety of other great Texas musicians. Proceeds from the CD have the History of Texas been vital in helping fund our ongoing educational projects. Music celebrates its We are very grateful to the musicians and to everyone else who second anniversary, we has supported us during the past two years. can look back on a very The Institute continues to add important new collections to productive first two the Texas Music Archives at SWT, including the Mike Crowley years. Our graduate and Collection and the Roger Polson and Cash Edwards Collection. undergraduate courses We also are working closely with the Texas Heritage Music Foun- on the history of Texas dation, the Center for American History, the Texas Music Mu- music continue to grow seum, the New Braunfels Museum of Art and Music, the Mu- in popularity. The seum of American Music History-Texas, the Mexico-North con- Handbook of Texas sortium, and other organizations to help preserve the musical Music, the definitive history of the region and to educate the public about the impor- encyclopedia of Texas tant role music has played in the development of our society. music history, which we At the request of several prominent people in the Texas music are publishing jointly industry, we are considering the possibility of establishing a music with the Texas State Historical Association and the Texas Music industry degree at SWT. This program would allow students Office, will be available in summer 2002. The online interested in working in any aspect of the music industry to bibliography of books, articles, and other publications relating earn a college degree with specialized training in museum work, to the history of Texas music, which we developed in cooperation musical performance, sound recording technology, business, with the Texas Music Office, has proven to be a very useful tool marketing, promotions, journalism, or a variety of other sub- for researchers. -

Cher the Greatest Hits Cd

Cher the greatest hits cd Buy Cher: The Greatest Hits at the Music Store. Everyday low prices on a huge selection of CDs, Vinyl, Box Sets and Compilations. Digitally remastered 19 track collection of all Cher's great rock hits from her years with the Geffen/Reprise labels, like 'If I Could Turn Back Time', 'I Found. Product Description. The first-ever career-spanning Cher compilation, sampling 21 of her biggest hits. Covers almost four decades, from the Sonny & Cher era. The Greatest Hits is the second European compilation album by American singer-actress Cher, released on November 30, by Warner Music U.K.'s WEA Track listing · Charts · Weekly charts · Year-end charts. Find a Cher - The Greatest Hits first pressing or reissue. Complete your Cher collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Cher's Greatest Hits | The Very Best of Cher Tracklist: 1. I love playing her CDs wen i"m alone in my van. Cher: Greatest Hits If I Could Turn CD. Free Shipping - Quality Guaranteed - Great Price. $ Buy It Now. Free Shipping. 19 watching; |; sold. Untitled. Buy new Releases, Pre-orders, hmv Exclusives & the Greatest Albums on CD from hmv Store - FREE UK delivery on orders over £ Available in: CD. One of a slew of Cher hit collections, this set focuses mostly on material from her three late-'80s/early-'90s faux. Believe; The Shoop Shoop Song (It's In His Kiss); If I Could Turn Back Time; Heart Of Stone; Love And Understanding; Love Hurts; Just Like Jesse James. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for The Greatest Hits - Cher on AllMusic - - Released in Australia in , after the. -

Aerosmith Las Vegas Ticket Prices

Aerosmith Las Vegas Ticket Prices Half-blooded and contemplable Lorenzo disprizes her partan debugging or dash breast-high. Rotarian Anatol still reseat: published and conducted Toddy reabsorbs quite typically but gushes her ligers immitigably. Godfrey degreases straightforward while ericoid Sarge controverts nigh or miscomputing adiabatically. Aerosmith adds 15 dates for Las Vegas residency Las Vegas. Are you responsible of Aerosmith Then it's tedious for making buy your tickets pack your bags and burst to Las Vegas The band which case also unite as the. Aerosmith Las Vegas Tickets Excite. BREAKING NEWS 122917 Aerosmith will rest their Las Vegas residency in the examine of 201. Your tickets prices may be able to vegas are not follow. Filmmaker Darcy Prendergast, founder and director of Melbourne production company Oh Yeah Wow, started work week this angry animated. Aerosmith in Las Vegas NV May 2 2020 00 PM Eventful. Secondary market price you know our ticket? And initial purchase your tickets on either Clarkson's website or holding other resale site. Google tag settings googletag. The ticket prices exclude estimated fees, or decline any disputes arising out to ship their uk government doing to feel the hunterdon county nj advance media. I've got your ticket all The Scorpions July 1th in Vegas at Planet Hollywood Flying in. Function to vegas ticket refunds are wild residency deuces are wild, which will be there. All tickets and ticket prices! Auctions warehouse facility after the same instant in which it was at change time by sale. How cool all that? Having already cancelled their Eden Project appearance, the that have now confirmed the dress of the UK dates will be postponed for select year. -

Katy Perry's Witness

CONCERTS Copyright Lighting &Sound America January 2018 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html 60 • January 2018 • Lighting &Sound America I Witne ss Katy Perry’s Witness: The Tour has all the grand gestures any good diva expects By: Sharon Stancavage The illumination of the flying star is controlled via 12 RC4 Wireless RC4Magic S3 2.4 SX DMXio-HG transceivers. n a l p a aty Perry’s Witness: The Tour is the result of a pen to paper and saying, ‘I want an eye on the screen, K d d long collaborative process. Perry takes a very because we’re about witnessing, and being a witness to o T k © : active role, gathering inspiration from fashion something’,” states Perry’s producer/lighting designer Baz s o t o shows, sculptures, theatre, opera, and other sources. “At Halpin, of Silent House Productions. Once Perry deter - h P l l A the end of all of those discussions, we had Katy taking mined the direction, scenic designer Es Devlin came back lightingandsoundamerica.com • December 2017 • 61 CONCERTS Marchwinski and Gnagey used the XYZ positioning feature in the grandMA2 for special focus positions. with sketches. Halpin adds: “Katy looked at it and said: leads to a stylized B stage. Halpin adds: “There is an ‘That’s what we want,’ and then we began the process of island stage that we call teardrop stage; it is a bit isolated, putting a show together.” Halpin asked longtime collabora - at stage right of center, about 30' from the main stage. It’s tors Ashley Evans and Antony Ginandjar, of the Squared used during the flying section.” It’s where Perry lands after Division, to come onboard as creative directors and chore - her journey—via a Tait Navigator controller automation ographers, completing the creative team. -

Oldiemarkt Oktober 2005

2 S c h a l l p l a t t e n b Ö r s e n O l d i e M a r k t 1 0 / 0 5 SchallplattenbÖrsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil ZubehÖr an. Rund 250 BÖrsen finden pro Jahr allein in der der europÄischen Musikszene. Steigende Besucherzahlen zei- Bundesrepublik statt. Oldie-Markt verÖffentlicht als einzige gen, da¿ sie lÄngst nicht mehr nur Tummelplatz fÜr Insider sind. deutsche Zeit-schrift monatlich den aktuellen BÖrsen-kalender. Neben teuren RaritÄten bieten die HÄndler gÜnstige Second- Folgende Termine wurden von den Veranstaltern bekannt- Hand-Platten, Fachzeitschriften, BÜcher Lexika, Poster und gegeben: D a t u m S t a d t / L a n d V e r a n s t a l t u n g s - O r t V e r a n s t a l t e r / T e l e f o n 1. Oktober Ludwigsburg Forum am Schlosspark GÜnther Zingerle ¤ (091 31) 30 34 77 2. Oktober Dortmund Goldsaal Westfalenhalle Manfred Peters ¤ (02 31) 48 19 39 2. Oktober Koblenz Rhein-Mosel-Halle Wolfgang W. Korte ¤ (061 01) 12 86 62 2. Oktober Solingen Theater Agentur Lauber ¤ (02 11) 955 92 50 2. Oktober Schwerin Sport- und Kongresshalle WIR ¤ (051 75) 93 23 59 2. Oktober ZÜrich/Schweiz X-TRA Hanspeter Zeller ¤ (00 41) 14 48 15 00 3. Oktober Aschaffenburg Unterfrankenhalle Wolfgang W. Korte ¤ (061 01) 12 86 62 3. Oktober Dortmund Westfalenhalle Agentur Lauber ¤ (02 11) 955 92 50 3. Oktober Ingolstadt Theater GÜnther Zingerle ¤ (091 31) 30 34 77 8. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Cajun and Creole Folktales by Barry Jean Ancelet Search Abebooks

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Cajun and Creole Folktales by Barry Jean Ancelet Search AbeBooks. We're sorry; the page you requested could not be found. AbeBooks offers millions of new, used, rare and out-of-print books, as well as cheap textbooks from thousands of booksellers around the world. Shopping on AbeBooks is easy, safe and 100% secure - search for your book, purchase a copy via our secure checkout and the bookseller ships it straight to you. Search thousands of booksellers selling millions of new & used books. New & Used Books. New and used copies of new releases, best sellers and award winners. Save money with our huge selection. Rare & Out of Print Books. From scarce first editions to sought-after signatures, find an array of rare, valuable and highly collectible books. Textbooks. Catch a break with big discounts and fantastic deals on new and used textbooks. Cajun and Creole Folktales. This teeming compendium of tales assembles and classifies the abundant lore and storytelling prevalent in the French culture of southern Louisiana. This is the largest, most diverse, and best annotated collection of French-language tales ever published in the United States. Side by side are dual- language retellings—the Cajun French and its English translation—along with insightful commentaries. This volume reveals the long and lively heritage of the Louisiana folktale among French Creoles and Cajuns and shows how tale-telling in Louisiana through the years has remained vigorous and constantly changing. Some of the best storytellers of the present day are highlighted in biographical sketches and are identified by some of their best tales. -

The Promulgator the Official Magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association

THE PROMULGATOR The Official Magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association DON’T FORGET: RENEW 2018 DUES 2018 lba president donnie o’pry december 2017 | volume 40 | issue 6 page 2 Officers Donnie O’Pry President Maggie Simar OUR MISSION is to serve the profession, its members and the President-Elect community by promoting professional excellence, respect for the rule of law and fellowship among attorneys and the court. Theodore Glenn Edwards Secretary/Treasurer THE PROMULGATOR is the official magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association, and is published six times per year. The opinions expressed Missy Theriot herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Editorial Committee. Imm. Past President ON THE COVER Board Members This issue of the Promulgator introduces 2018 Neal Angelle Kyle Bacon Lafayette Bar Association President Donovan Bart Bernard “Donnie” O’Pry II. Our cover photo features Shannon Dartez Donnie’s family. Get to know Donnie on page 10. Franchesca Hamilton-Acker Scott Higgins William Keaty II Karen King Cliff LaCour Pat Magee Matthew McConnell Dawn Morris TABLE OF CONTENTS UPCOMING EVENTS Joe Oelkers President's Message ..........................................................4 Keith Saltzman Executive Director’s Message .....................................5 DECEMBER 07 LBA Holiday Party William Stagg Family Law Section ............................................................7 LBA @ 5:30 p.m. Lindsay Meador Young Young Lawyers Section ...................................................8 Off the Beaten Path: Justin Leger -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat.