Death in the Port City: a Look at Gravestones, Religion, and Status In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2020 Activity Guide

Fall 2020 Activity Guide MOBILE PARKS AND RECREATION WWW.CITYOFMOBILE.ORG/PARKS FALL @mobileparksandrec @mobileparksandrec 2020 FROM THE SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PARKS AND RECREATION Greetings, As I write this letter, six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I think about all the changes we’ve had to endure to stay safe and healthy. The Parks and Recreation team has spent this time cleaning and organizing centers, creating new virtual and physical distancing activities, and most importantly continuing to provide meals to our seniors and youth. I would like to share many of the updates that happened in Parks and Recreation since March. • Special Events is now under the umbrella of Parks and Recreation. • Community Centers received new Gym floors, all floors were buffed and deep cleaned. Staff handmade protective face masks for employees, and over 28,123 meals were distributed to children ages 0-18. • Azalea City Golf Course staff cleaned and sanitized clubhouse, aerated greens, driving range, trees and fairways, completed irrigation upgrade project funded by Alabama Trust Fund Grant, contractor installed 45’ section of curb in parking lot and parking lot was restriped, painted fire lane in front of clubhouse, painted tee markers & fairway yardage markers and cleaned 80 golf carts. • Tennis Centers staff patched and resurfaced 6 Tennis courts, 118 light poles were painted, 9.5 miles of chain link fence was painted around 26 Tennis courts, 3 storage sheds were painted, 15 picnic tables were painted, 8 sets of bleachers were painted & park benches, 14 white canopy frames were painted plus 28 trash bins, court assignment board painted & 26 umpire chairs assembled. -

Mobile Civic Center Offers to Help Minimize the Impact to Your Event

September 9, 2020 To: Krewe Chairperson, Name of Krewe Fr: Kendall Wall, ASM Mobile, General Manager Re: Mardi Gras 2021 I hope this finds you and your loved ones safe and healthy. This letter is an invitation to join us to develop plans for a safe and memorable Mardi Gras 2021. Your Event Manager will be reaching out to you in the next few days to coordinate an in-person or virtual meeting for you and your representatives. We know that with your partnership and insight, we can and will find a way to reimagine an event that still honors your unique traditions. As Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson stated in his August 28th letter to the Mobile Mardi Gras Parading Association and the Mobile Carnival Association, we must think creatively about ways to adapt our traditional celebrations to the ever-changing environment and the challenges that COVID-19 presents. The great news about this challenge is that our team has been working proactively for the past several months to determine ways that we can better utilize the multitude of space that the Mobile Civic Center offers to help minimize the impact to your event. In the following pages, you will find some general protocols for all of our upcoming events, as well as some guidelines that are unique to Mardi Gras festivities. Please remember that every organization that we host has different needs and goals, and our staff is committed to customizing plans and procedures - within the appropriate guidelines - to ensure your event is successful and safe. The final attendance count will be a result our staff meeting with your ball chairman. -

ALABAMA STATE PORT AUTHORITY SEAPORT March 20 11 Alabama Seaport Published Continuously Since 1927 • March 2011

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE A L A B A M A OF THE ALABAMA STATE PORT AUTHORITY SEAPORT MARCH 20 11 Alabama Seaport PuBlishED continuOuSly since 1927 • marCh 2011 On The Cover: an aerial view of the alabama State Docks, looking south to north from the mcDuffie Coal Terminal to the Cochrane africatown Bridge. 4 12 Alabama State Port Authority P.O. Box 1588, Mobile, Alabama 36633, USA P: 251.441.7200 • F: 251.441.7216 • asdd.com Contents James K. Lyons, Director, CEO Larry R. Downs, Secretary-Treasurer/CFO recovery In 2010 Points To growth in 2011 .................................................4 FinanCial SerVICes Coalition of alabama waterways association ............................................10 Larry Downs, Secretary/Treasurer 251.441.7050 Linda K. Paaymans, Vice President 251.441.7036 Port authority Offers helping hand to restore mobile’s COmptrOllEr Pete Dranka 251.441.7057 Dog river Park Shoreline............................................................................... 12 Information TechnOlOgy Stan Hurston, manager 251.441.7017 human Resources Danny Barnett, manager 251.441.7004 In memoriam: marrion rambeau ..................................................................16 Risk managEmEnT Kevin Malpas, manager 251.441.7118 InTErnal auditor Avito DeAndrade 251.441.7210 made in alabama: heat Transfer Products group grows in alabama ...18 Marketing Port Calls: monroeville, ala. is for the Birds…The mockingbirds ........ 20 Judith Adams, Vice President 251.441.7003 Sheri Reid, manager, Public affairs 251.441.7001 Currents ............................................................................................................ 24 Pete O’Neal, manager, real Estate 251.441.7123 Of men & Ships: The raider Atlantis .......................................................27 Pat Scott, manager, Fixed assets 251.441.7113 John Goff, manager, Theodore Operations 251.443.7982 Operations Departments H.S. “Smitty” Thorne, Executive Vice President/COO 251.441.7238 Bradley N. -

MAGNOLIA CEMETERY NEWSLETTER Page 3

MagnoliaTHE FRIENDS OF MAGNOLIAMessenger CEMETERY NEWSLETTER www.magnoliacemetery.com “Remove not the ancient Landmark” Summer 2020 Pandemics Past: Yellow Fever Mobile has survived over 300 years despite a litany of epidemics and pandemics and our most historic cemeteries are testament to our neighbors who did not. It seems to have all begun back in 1704 when a vessel called The Pelican arrived from Havana. On board were 23 French girls looking for a new life – and a husband. But also aboard was more than cargo and passengers, for it also carried the first known yellow fever epidemic. Several had died en route and others were sick as the ship docked. Little did anyone realize that among the passengers and crew were mosquitoes from Cuba carrying Church Street Graveyard was created after the original burying the dreaded fever. As they drifted ashore they infected ground near the Cathedral was filled by fever victims. local mosquitoes, spreading the fever to the shore. obtained land for the Church Street Graveyard and before Gruesome Symptoms the transaction was completed the burials had begun. Within four hours of being bitten by one of these As the population of cities across the South grew with new mosquitoes a victim would begin showing symptoms: a arrivals, so did the number of deaths from fever outbreaks. flushed face accompanied by fever and chills. He either In 1823, the first known quarantine was established by improved or got worse. Jaundice would turn the skin an New Orleans against travelers from up river Natchez unhealthy shade of yellow, hence the name. -

View Renaissance Hotel; the Economic Development Flagging of the Holiday Inn; and the Ground Breaking for the Hampton Inn

A publication of Main Street Mobile, Inc. DV OWNTOWNOLUME 2 • NUMBER 1 •A DECEMBERLLIANCE 2007-JANUARYNEWS 2008 GLOBAL TRENDS AFFECTING DOWNTOWN MOBILE By Carol Hunter skills, American universities are graduating fewer students in science and engineering. Downtown Mobile should consider harnessing the power of local institutions of higher With today’s international trade, instant communications and intercontinental travel, learning by housing facilities to foster research and education in the city center. We are global trends affect all of us, even in Mobile. Whether those affects are positive or neg- particularly well poised to develop a relationship with the fine arts departments of our col- ative depends on how we prepare for them. Progressive Urban Management leges and universities. Associates, in consultation with the International Downtown Association, has developed a body of research that identifies major global trends affecting downtowns and recom- Traffic Congestion and mends tangible actions. The following is a summary of the research with recommenda- the Value of Time tions adapted for downtown Mobile. Traffic congestion cost Americans $63 billion and 47 hours of average Changing American annual delay in 2003, and experts sug- Demographics. gest that building more roads is doing Three generations are little to stem rising traffic congestion. shaping America and the Additionally, a commuter living an growth of downtowns, each As gas prices and congestion increase, more hour’s drive from work annually spends with distinctly different demo- smart cars may be seen downtown. the equivalent of 12 work weeks in the graphics and behaviors. The car. It is not uncommon to have an hour’s commute in Mobile and Baldwin Counties. -

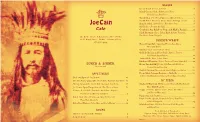

Joe Cain Cafe

SALADS Caesar Salad, Croutons, Parmesan ....................................... 8 Mixed Greens Salad, Alabama Goat Cheese, Candied Pecans, Strawberries ..................................... 8 Greek Salad, Feta, Olives, Pepperoncini, Marinated Onions .............. 9 *Cobb Salad, Blue Cheese, Bacon, Tomato, Boiled Egg, Avocado ......... 9 Spinach Salad, Candied Pecans, Blue Cheese, Pear ....................... 8 Add Chicken or Shrimp to Any Salad ......................................... 5 Combine Any Salad or Soup and Half a Panini ......... 11 Salad Dressings: Caesar, Italian, Ranch, Balsamic Vinaigrette, Blue Cheese, Sesame Vinaigrette The Battle House, A Renaissance Hotel & Spa 26 N. Royal Street • Mobile, Alabama 36602 251-338-4334 PANINIS/WRAPS Shaved Prime Rib, Caramelized Onions, Swiss Cheese, Horseradish Cream ............................................... 11 Chicken Salad, Candied Pecans, Grapes ................................ 10 Grilled Chicken and Portobello, Spinach, Tomatoes, Fresh Mozzarella and Balsamic ................................... 11 Turkey Club, Bacon, Lettuce, Tomato ................................... 11 Blackened Flounder, Lettuce, Tomato and Lemon/Caper Aioli ........ 11 LUNCH & DINNER House Smoked BBQ Pork, Cole Slaw and Dill Pickle on 10:30 am until Cornmeal Dusted Keiser Bun .................................... 10 Grilled Chicken Cheesesteak, Sautéed Peppers and Onions ......... 10 APPETIZERS House Made Pastrami Rueben, on Marbled Rye ...................... 10 All Panini’s And Wraps Come with Premium Kettle -

130916710797000000 Lagniap

2 | LAGNIAPPE | November 12, 2015 - November 18, 2015 LAGNIAPPE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• WEEKLY NOVEMBER 12, 2015 – N OVEMBER 18, 2015 | www.lagniappemobile.com Ashley Trice BAY BRIEFS Co-publisher/Editor The city of Orange Beach recently [email protected] unveiled the route of a $28 million Rob Holbert bridge over the Intrastate Canal. Co-publisher/Managing Editor 5 [email protected] COMMENTARY Steve Hall Reviewing two years of Mayor Sandy Marketing/Sales Director [email protected] Stimpson’s new government. Gabriel Tynes 14 Assistant Managing Editor [email protected] BUSINESS Dale Liesch The Dauphin Square shopping Reporter center just east of Interstate 65 is [email protected] getting a million-dollar renovation. Jason Johnson 18 Reporter [email protected] CUISINE Eric Mann Renowned New Reporter [email protected] CONTENTS Orleans chef John Besh stays grounded Kevin Lee Associate Editor/Arts Editor in the wake of fame, [email protected] discussing his latest Andy MacDonald cookbook and his life Cuisine Editor in the bayou. [email protected] Stephen Centanni Music Editor [email protected] 2020 J. Mark Bryant Sports Writer COVER [email protected] The Mobile County Stephanie Poe Racing Commission, Copy Editor [email protected] which governs Mobile Greyhound Park Daniel Anderson Chief Photographer and distributes its tax [email protected] proceeds, recorded Laura Rasmussen the lowest financial Art Director www.laurarasmussen.com allocation of its history in 2014. Brooke Mathis Advertising Sales Executive 2626 [email protected] Beth Williams ARTS Advertising Sales Executive The third book in Ann Pond’s Mardi [email protected] Gras trilogy debunks the myth of the Misty Groh man credited for Mobile’s pre-Lenten Advertising Sales Executive 28 [email protected] celebration. -

Mary Ward Brown

The Journal of the Alabama Writers’ ForumNAME OF ARTICLE 1 VOL. 8, NO. 4 FIRST DRASPRINGFT 2002 KEVIN GLACKMEYER Harper Lee Award Winner MARY WARD BROWN It Wasn’t All Dancing 2NAME OF ARTICLE? From the FY 02 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Executive Director President PETER HUGGINS Auburn Immediate Past President Recently the Alabama Writers’ Forum teamed up KELLEE REINHART Tuscaloosa with the Alabama Center for the Book and the Ala- Vice-President bama State Council on the Arts (ASCA) to present BETTYE FORBUS Dothan grant-writing workshops in Bay Minette and Monte- Secretary vallo. Our agenda was simple: we hope to generate LINDA HENRY DEAN Jeanie Thompson Auburn more literary arts grant proposals to ASCA. Treasurer The turnout at both workshops was encouraging, ED GEORGE Montgomery and people came from towns as small as Atmore and as large as Birmingham. Writers’ Representative Clearly, people want to understand the process better. The nuts and bolts of state AILEEN HENDERSON Brookwood arts grant writing are pretty simple, and the ASCA staff – Randy Shoults is your lit- Writers’ Representative erature guy – will walk you through every step of the applications. There’s no need DARYL BROWN Florence to throw up your hands and fret – it’s relatively straightforward. JOHN HAFNER If you do plan to request ASCA funds for your literary venture, be it a magazine, Mobile a reading series, a visiting writer in your community, or even a fellowship, please re- WILLIAM E. HICKS Troy member to canvass your Alabama literary resources. The Forum staff make it our RICK JOURNEY business to keep up with the location of writers, magazines, presses, and confer- Birmingham FAIRLEY MCDONALD ences. -

Bella Terra Plans Annual Mardi Gras Trip

Bella Terra RV Resort Newsleer Volume 2, Issue 2 | February 2014 BELLA TERRA PLANS ANNUAL MARDI GRAS TRIP It is a lile known fact that the birthplace of Joe Cain Day, with many tradions that go and eventually wail at Joe's grave. In stark Mardi Gras in the United States happens to with it. contrast, the Mistresses will wear all red be in Mobile, Alabama. However, during complete with identy-hiding veil, walk be- Some of these tradions include a street the country’s Civil War, the fesvies hind the coal cart and exclaim that "Joe re- party in front of Joe’s home in the historic ceased. ally loved us the most!" The two groups will Oakleigh Garden District, with appearances even have "fights" and bicker with one an- Joe Cain Day is celebrated in Mobile, AL on by Joe Cain's Merry Widows and the Mis- other, to the on-watcher's delight. the Sunday before Fat Tuesday to honor the tresses of Joe Cain. The laer two super- life of the person credited with To catch all the fun, join your fellow bringing Mardi Gras back to Mo- revelers as we ride from Bella Terra bile aer the Civil War. to Mobile by bus. We are charging $25 per person and the bus only In 1867, Joe Cain, along with 6 holds 56 passengers. Please sign up other Confederate veterans who early! called themselves The Lost Cause Minstrels, paraded through the The bus will depart Bella Terra at streets of Mobile in a decorated 8:30 am on Sunday, March 2nd and coal cart. -

Spacious Cou Draught B Yard Tur ‡Great F Beer ‡Full Bar

to the the fun you Mo- Wave com- might restau- Mobile in and much enjoy The downtown where BEST answer: so you ride easy and in to AROUND is downtown districts, your You do that contact. are downtown back Spacious Couurtyard Great Food RUN There in and board sit service. you Here’s so historic moda! WE CIRCLES MOBILE’S OFFERINGS! see Mobile downtown and in. shopping. Draught Beer Full Bar on you’re shuttle where all If parks, and it behind weather- 'DXSKLQ6WUHHW 77DDTXHULD fit exploring from DOWNTOWN DINING & SHOPPING GUIDE way. 226. 6HUYLQJIURP DP XQ OLW 0LGQLJKWGD\V DZHHN car the can x information of you the including convenient museums your you makes /LTXLG/RXQJH 6XVKL get and more 6HUUYYLQJIURP DP XQ OLW DP GD\V DZHHN along be. how stops, can Leave hotels, moda! For free THINGS TO SEE AND SAVOR to 20 regardless 2SHQ8Q OLW DP 'D\V $<<HHDU 251-344-6600 mydowntownmobile.org moda! bile’s fort, scenery moda! want wonder with rants, at 'DXSKLQ 6WUHHW'RZQWRZQ0RE OL H Please like us on facebook - OK Bicycle Shop 'DXSKLQ 6WUHHW'RZQWRZQ0RE OL H 2SHQ SPXQW OL 0LGQLJKW 6XQGD\ 0RQGD\ 2SHQ SPXQW OL DP 7XHVGD\WKUX6DWXUGD\ 'DXSKLQ6WUHHW 7DTXHULDVHUYLQJXQW OL PLGQLJKW /LTXLG/RXQJH 6XVKLVHUYLQJ XQW OL DP Please like us onn facebook - Liquid Sushi Lounge 3 5 ( 0, 8 0 6 7($ . 6 % 8 5 * (5 6 'DXSKLQ 6WUHHW'RZQWRZQ0RE OL H 2SHQ SPXQ OLW SP7XHVGD\WKUX6DWXUGD\ 5HVHUUYYD LW RQVVXJJHVWHG Please like us on facebook - Union - Downtown Mobile Downtown Food DDelivery 251.643.TTOGO FOR MENUS, HOURS AND DAAYYS AVAILABLE VISIT: Facebook.com//DowntownGrubRunnners 1. -

Ghosts of Old Mobile

GHOSTS OF OLD MOBILE Ghosts OF OLD MOBILE BY MAY RANDLETTE BECK Published for the Historic Mobile Preservation Society THE HAUNTED BOOK SHOP MOBILE, ALABAMA 1946 COPYRIGHT, 1946 by MAY RANDLETTE BECK Printed and Bound By GILL PRINTING & STATIONERY CO. Mobile, Alabama Engravings By GULF ST ATES ENGRAVING CO. Mobile, Alabama TEXTS MA y RANDLETT£ BECK VERSES CAROLINE McCALL ---- DRAWINGS WILLIAM B. BusH DEDICATED To MY SISTER FAN LOUISE RANDLETTE 1883-1939 With her cheerful happy nature she scattered sunshine and sowed the seed of her beautiful philosophy of living an2ong all who knew her .. Vll MOTTO OF '' THE .ANCIENT MAR IN ER'' "I can hardly believe that in the universe the invisible beings are more than the visible. But who shall reveal to us the nature of them all, the rank, the relationships, the distinguishing features and the offices of each? What is it they do? Where is it they dwell? Always about the knowledge of these wonders the mind of man has circled nor ever reached it." -Translated from the Latin of Buckner and used -by Coleridge . Vlll ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere thanks go to all who have helped with this book. To Caroline McCall, for her generous assistance and encouragement during my explorations down highways and byways looking for ghosts. Research in any activity demands time and thought and energy but it has been fun working together. Many times the wee sma' hours have found us in close communion at our ghostly task, attempting to recapture the spirits of another day. Caroline, with her gifted touch, can transform a plain statement of facts into a poem. -

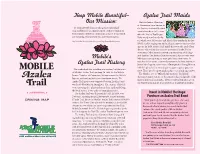

251-444-7144 Azaleas Are $20 Each. Decide on Quantity Desired

Azaleas are $20 each. Decide on quantity desired Keep Mobile Beautiful 2029B Airport Blvd Ste 230 Mobile, AL 36606 251-444-7144 ) Spring Hill Trail Hill Spring HILLCREST Trail Two Trail S TADIUM BLVD CIRCLE USA USA SOUTH ALABAMASOUTH Sky Ranch/Cottage Hill Trail Hill Sky Ranch/Cottage O UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY LD SH LD . S . D V L B Y T I S R E V I N U US ELL R ELL A DA . D R S I L O P O R T E M E D JAPONICA R LN. D. N . USA USA DR . AY S C REGENTS W . O T T N. UNI VERSITY BLVD. A G Trail Three Trail E S . H U I N L I V L E R R S I T D Y B . L V D . D V L B Y T I S R E V I N U . S G A IL B LA I T R AIRPORT BLVD.. AIRPORT & D MARCHFIELD S DR. W. P U R ES GAIN W I L S K C I H N WEAT W O S A O E L N M M D L S H E ERFOR H E M B L Y D O O W D L I AR W L C R MICHA N R H D E F D P S A I T E R B Y L . A D JAPONICA LN. HERE U DR END N R . E BL EL M . A R V D D HILLCREST LN. W . I M B L M E D U O S N E U M D R W.