Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization Did the Soviets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

2020-21 Candidates Tournament ROUND 9

2020-21 Candidates Tournament ROUND 9 CATALAN OPENING (E05) easy to remove and will work together with the GM Anish Giri (2776) other pieces to create some long-term ideas. GM Wang Hao (2763) A game between two other top players went: 2020-2021 Candidates Tournament 14. Rac1 Nb4 15. Rfd1 Ra6 (15. ... Bxf3! 16. Bxf3 Yekaterinburg, RUS (9.3), 04.20.2021 c6 is the most solid approach in my opinion. I Annotations by GM Jacob Aagaard cannot see a valid reason why the bishop on f3 for Chess Life Online is a strong piece.) 16. Qe2 Nbd5 17. Nb5 Ne7 18. The Game of the Day, at least in terms of Nd2 Bxg2 19. Kxg2 Nfd5 20. Nc4 Ng6 21. Kh1 drama, was definitely GM Ding Liren versus Qe7 22. b3 Rd8 23. Rd2 Raa8 24. Rdc2 Nb4 25. GM Maxime Vachier-Lagrave. Drama often Rd2 Nd5 26. Rdc2, and the game was drawn in Ivanchuk – Dominguez Perez, Varadero 2016. means bad moves, which was definitely the case there. Equally important for the tournament 14. ... Bxg2 15. Kxg2 c6 16. h3!N 8. ... Bd7 standings was the one win of the day. GM Anish Giri moves into shared second place with this The bishop is superfluous and will be The real novelty of the game, and not a win over GM Wang Hao. exchanged. spectacular one. The idea is simply that the king The narrative of the game is a common one hides on h2 and in many situations leaves the 9. Qxc4 Bc6 10. Bf4 Bd6 11. -

An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev by Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All Rights Reserved

Correspondence Chess News Issue 31 - 14 January 2001 An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev By Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All rights reserved. How did you first get attracted to chess? Please also say something about your early chess development in Ukraine. I started to play in 1976 (at the age of six) and from 1977 onwards, I started to learn chess in the chess club (by the way, many players the world over think that chess was an obligatory discipline in the regular Soviet Schools – that’s not correct). Sometimes, I think that I started to look at chess seriously after my parents got divorced, but I’m not sure if it was the real impetus. In any case, I was quite able to play chess. It is easy to say as I scored many good results, especially at the age of 12-14 years. For instance, in the 1984 (at age 14), I shared second place (with the better tiebreak) with Ivanchuk (he was one year older) in the Ukrainian Junior Ch U- 17. Still, I’m not sure if I’m a born chess player. I remember, in 1984 I played in a junior tournament in Baku, and shared the first place there with Vladimir Akopian. Volodya is one year younger than me, and he was very small in 1984 J . We played an extremely complicated game, and I accepted his draw offer when my position was already better. I was quite afraid for him, as for the first time I saw a clearly more talented player than me. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

1 Najdorf Sicilian Focus on the Critical D5 Squar One the Most Common Openings in the Past 50 Years Is the Najdorf Variation Of

1 Najdorf Sicilian will try to keep full control over the d5 Focus on the Critical d5 Squar square, and try to maintain the possibility of placing and keeping a piece One the most common openings in the on d5. Fully controlling the d5 square past 50 years is the Najdorf variation of allows white to affect both sides of the the Sicilian Defense. The Najdorf offers board. In order to assure that control, many different possibilities, starting from white wants to trade off black pieces extremely sharp, poison pawn variation that can control d5. For example, he (1. e4, c5 2. nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 wants to play with Bg5, in order to trade Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Bg5 e6 7. f4 Qb6 8. off the Knight on f6. He also will Qd2 Qxb2! ) to extremely positional lines increase the number of his own pieces (1. e4, c5 2. nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 that can control d5, with maneuvers like Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Be2 e5 7. Nb3 ... ) bishop to c4, then b3, and the knight on Somewhere between those two lines is f3 going to d2-c4-e3. It seems that white the following position, which I will try to has full control of the situation. So why explain. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 does black choose to create this pawn 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Be3 e5 7.Nf3 structure? The answer is because this is Diagram one of the rare Sicilian pawn structures abcdef gh that gives the black side a slight space advantage. -

Mirotvor Schwartz CHESS PLAYERS on STAMPS

Mirotvor Schwartz CHESS PLAYERS ON STAMPS This is a list of chess players depicted on stamps, along with the actual stamps. Each player’s name is clickable – it will take you to the player’s Wikipedia page (or, if one does not exist, to a different chess-related page), where you can view the player’s biography and details of their career. If a philatelic item depicts a specific chess contest, said contest is mentioned in italics following the item. For each chess player, a short biography is given. It includes two types of competitions: 1.World Championship and its affiliate contests (Candidates Tournament, Interzonal Tournament, World Cup, FIDE Grand Prix, FIDE Grand Swiss Tournament), as well as major team competitions (Olympiads, World Team Championship, European Team Championship). 2.An event depicted in my “Chess History on Stamps” collection, no matter how minor or seemingly insignificant. After each contest and year in a player’s biography, the following information is given in brackets: 1.The place in which the player (or their team) finished the competition. Note that “(?)” means the place is unknown at the time, while “(0)” means the player or the team was participating as a non- contestant. 2.In a team competition, the following personal achievements of the player: -- being the best player at their board (BB) -- showing the best individual performance of the tournament (BP) If an achievement is actually depicted on a stamp or a philatelic item, the year of said achievement is bolded. 1 EXAMPLE: Let’s look at Nino Batsiashvili: -

The Modernized Najdorf First Edition 2018 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2018 Milos Pavlovic

The Modernized Najdorf First edition 2018 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2018 Milos Pavlovic All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Software: Hub van de Laar Proofreading: Bernard Carpinter Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510389 D/2018/13730/20 The Modernized Najdorf Milos Pavlovic Thinkers Publishing 2018 Table of Contents Key to Symbols ..................................................................................................... 4 Preface ................................................................................................................. 5 Chapter 1 - 6th Move Sidelines .............................................................................. 7 Chapter 2 - The 6.f4 Variation ............................................................................. 41 Chapter 3 - The 6.Bc4 Variation......................................................................... 61 Chapter 4 - The 6.g3 Variation .......................................................................... 101 Chapter 5 - The 6.Be2 Variation...................................................................... -

CHESS IS WHERE YOU FIND IT! CHESS Che.S.S Ha.S Joy and Solace for All-Regardless 0/ Race, Creed, Color Or Condition

INhi s invaluahle treatise, My System, Nim 53 K- KS !! • • • • zovich makes this cryptic statement: "Tar White can commit 'Hli·male by 53 P takowcr is, it! my opinion, without question Qo. Q- Xlt 5·] K - K7, Q- lJl matc. ~ ::::. the third be:;! endgame a rtist of a ll living 53 . P-N4 55 Q-K7t K-Nl ~J masters." One wonders who his two superiors 54 P_Q7 Q-QR5 56 Q-B7t K-Rl 57 K-B8 Resigns were. Whom d id Nimzovich have in m ind? Artel· 57 . .. Q- Jtlt, 58 Q- K S, Q- B6 (to ~ . Th ere was Lasker, former Wodd's Cham - ~top 59 Q- lt5 mnte) 59 K- lJH, K - H2 60 pion, whose consummate endgame skill was Q- N8t and mate next move follows. almost legendary. There was another ex Champion, th e mighty CapabJanca, who delib· l-IEHE is a problem whkh you might try on your friend who ··simply ("annot soh·c eratel y steered for the ending in his games as any jlroblem at all"· The terms fire: it wa s there that he could display his fahulous White to mate In o ne mo\'e .- It is by technique to best advantage. There wa s the 'V. A. Shinkman. Irvin9 Cherney reigning Champion himself, the peerless Alek- hine, who played the endings with daz;.:l illg hdlliunccf Then, to complicate matters, there was Rubinstein, who wa s - -to quote Dr. Harlllak- "the suhlime endgame virtuoso of a ll Lim e." And whal about Nimzovich him sel f? He must have had a leaning toward hi s own ab il ities in th at branch of the game. -

A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague – Candidates Tournament 2020

A FEAST OF CHESS IN TIME OF PLAGUE CANDIDATES TOURNAMENT 2020 Part 1 — Yekaterinburg by Vladimir Tukmakov www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniël Vanheirzeele Translator Izyaslav Koza Proofreader Bob Holliman Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Mieke Mertens Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague. Candidates Tournament 2020. Part 1 — Yekaterinburg Copyright © 2020 Vladimir Tukmakov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-092-1 D/2020/13730/26 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PRELUDE 11 THE PLAY Round 1 21 Round 2 44 Round 3 61 Round 4 80 Round 5 94 Round 6 110 Round 7 127 Final — Round 8 141 UNEXPECTED CONCLUSION 143 INTERIM RESULTS 147 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! a good move ?a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move only move =equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrifi ced material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage Black has a serious advantage +– White has a decisive advantage –+ Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is worse is Nnovelty +check #mate INTRODUCTION In the middle of the last century tournament compilations were ex- tremely popular. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

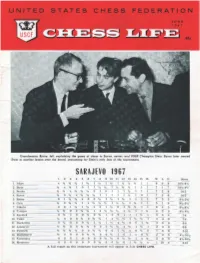

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication.