Hidden Figures on Perceptions of Engineering Using Arts-Based Research Methods Katherine A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidden Earth: Visualization of Geologic Features and Their Subsurface Geometry

The Hidden Earth: Visualization of Geologic Features and their Subsurface Geometry Michael D. Piburn, Stephen J. Reynolds, Debra E. Leedy, Carla M. McAuliffe, James P. Birk, and Julia K. Johnson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, New Orleans, LA, April 7-10, 2002. ABSTRACT Geology is among the most visual of the sciences, with spatial reasoning taking place at various scales and in various contexts. Among the spatial skills required in introductory college geology courses are spatial rotation (rotating objects in one’s mind), and visualization (transforming an object in one’s mind). To assess the role of spatial ability in geology, we designed an experiment using (1) web-based versions of spatial visualization tests, (2) a geospatial test, and (3) multimedia instructional modules built around innovative QuickTime Virtual Reality (QTVR) movies. Two introductory geology modules were created – visualizing topography and interactive 3D geologic blocks. The topography module was created with Authorware and encouraged students to visualize two-dimensional maps as three-dimensional landscapes. The geologic blocks module was created in FrontPage and covered layers, folds, faults, intrusions, and unconformities. Both modules had accompanying worksheets and handouts to encourage active participation by describing or drawing various features, and both modules concluded with applications that extended concepts learned during the program. Computer-based versions of paper-based tests were created for this study. Delivering the tests by computer made it possible to remove the verbal cues inherent in the paper-based tests, present animated demonstrations as part of the instructions for the tests, and collect time-to-completion measures on individual items. -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Fact to Fiction Drama

iNfotECh visualization. Involving teens in this type of analysis asks them to dive into the facts behind each scene in a movie fact to fiction drama. the truth behind movies based trUth oN fiLm on true stories Data, facts, and information may all be part of telling a story. annette Lamb However, truth is drawn from our own perspectives of au- thenticity. Someone who is a protester from one perspective may be a terrorist in the eyes of another. A fact to one person any movie dramas begin with a statement that they can be seen as an embellishment by someone else. are a true story, based on a true story, or inspired by The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010) by Re- Ma true story. These catchphrases can be confusing for becca Skloot is a popular work of nonfi ction in high schools both children and adults. across America. In 2017, a made-for-television fi lm was re- Film dramas and biographies such as Schindler’s List (R, leased. However, not all of the Lacks family members were 8.9, 1993) are often used in classrooms to help mature teens excited by the fi lm adaptation. They didn’t feel that the visualize real-world people and events, so it’s essential that movie accurately represented the family members. both students and their teachers are media literate and able The website History vs Hollywood <http://www.his- to distinguish fact from fi ction.Schindler’s List is an exam- toryvshollywood.com/> explores the connection between ple of a fi lm that has been praised for its educational merits fi lms and their roots in reality. -

Cinematherapy in Gifted Education Identity Development

Cinematherapy in Gifted Identity Development Kangas, Cook, & Rule Page 45 Journal of STEM Arts, Crafts, and Constructions Cinematherapy in Gifted Volume 2, Number 2, Pages 45-65. Education Identity Development: Integrating the Arts through STEM-Themed Movies Timothy C. Kangas Cedar Falls Community School District Michelle Cook and Audrey C. Rule The Journal’s Website: University of Northern Iowa http://scholarworks.uni.edu/journal-stem-arts/ Abstract Gifted students, because of their advanced development Introduction compared to peers, have emotional needs that require differentiated education programs. Asynchronous social and emotional development of gifted students often leads to Programming for gifted and talented students is identity issues. Cinematherapy can be used to help gifted under constant scrutiny to ensure that students are being students explore their identities through analysis of the challenged appropriately in academic situations whether actions of gifted characters in films. This practical article through the use of compacting curriculum, subject area or suggests STEM-themed movies with characters facing whole grade acceleration, or by providing opportunities for challenges useful for gifted student identity development. students to excel in both core and non-core subject areas. The Autonomous Learners Model is used to classify gifted Within many programs what risks being overlooked is the learners in the movies to assist teachers in matching movies to the needs of gifted learners. Tables of STEM-themed “whole” child, -

Hidden Figures: the Katherine Johnson Story by Rev

Hidden Figures: The Katherine Johnson Story By Rev. Deborah Coble How you experience a movie can vary greatly fascinated when Sara an Carolyn reminisced about depending on who you watch it with. I had the the days they knew Miss Katherine as a friend and privilege of watching the movie, Hidden Figures neighbor. with two ladies who grew up in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, the hometown of Katherine Right from the start Sara and Carolyn wanted to Coleman Goble Johnson, the main character in set the record straight. “I have no idea where they the film. The movie is set in the era of Project filmed that first part of the movie. That didn’t look Mercury, the first human spaceflight program of the like White Sulphur Springs,” “and Miss Katherine United States; John F. Kennedy; the Cold War; and grew up in town, just down from the church,” they Martin Luther King, Jr. — a season in our country’s shared. “But she definitely was known for counting history that was ripe with her steps [as depicted in the possibility but also rife opening of the film]. She knew with tension. exactly how many steps it was from her house down Church I met Sara Carter and Street to St. James Methodist Carolyn Bond, members of church,” Carolyn said. St. James United Methodist Church, in the lobby of The Coleman family is the historic Lewis Theater remembered by the African- in downtown Lewisburg, American community of White four days before Hidden Sulphur Springs as a nice Figures was nominated family. -

This Character Is Portrayed As Unfeminine and “Married” to Their Work. They Can Be Transformed by a Love Interest, but Reinf

Andra Campbell This is Dr. Flicker! We’re going to use her paper “Between Hey everyone! My names Andra and I want Brains and Breasts-Women Scientists in Fiction Film: On the to tell you about the Marginalization and Sexualization of Scientific Competence” to ways that women in look at ways women in STEM in media have been portrayed by looking at the common-stereotypes throughout films . STEM have been represented in media! Hi everyone, I’m Dr. Flicker! Stereotype 1… This character is portrayed as unfeminine and “married” to their work. They can be transformed by a love interest, but reinforce the stereotype that feminine women can’t be intelligent. Check out Dr. Peterson from the movie Spellbound (1945), or Amy Fowler from the Big Bang Theory (2007) for an example! Stereotype 2… This portrays a woman who must be “one of the guys” in order to prove herself. She is sometimes inferior to her male counterparts. An example is Dr. Leavitt from The Andromeda Strain (1971) or Dr. Augustine from Avatar (2009). This portrayal reinforces the negative stereotype that science is for “The Andromeda Strain (1971).” IMDb, www.imdb.com/ men. Stereotype 3… Dr. Sarah Harding from The Lost World: Jurassic Park This character has little (1997) is an example of significance towards The Naive Expert you may the scientific theme of recognize! the movie, is feminine, and often a love interest. Her naïveté often gets her in trouble, with a man “The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Universal, 1997).” Heritage rescuing her. Auctions, 2 Sept. 2018, movieposters.ha.com/itm/ movie-posters/science-fiction/the-lost-world- jurassic-park-universal-1997-lenticular-one- sheet-27-x-41-science-fiction/a/161835-51233.s. -

Gar Feb 2020

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Movies are shown daily at 2:00 Are you interested in hosting an 9:30 Pom-Pom Workout, AR Watermark 10:00 Line Dancing with Mary Jane, A February is and 6:30 p.m. in the Movie activity or Watermark University class Happy Exercise is or course? Contact Community Life 10:30 Popcorn & Trivia, KL Theater. Movie titles are University Courses 11:00 Speak French with Richard, F for more information and to get started displayed at the bottom of daily everyday at 1:30 Color Therapy, AR Black History as a Watermark University Faculty are Designated in Valentine's boxes. Check the movie 3:30 Karaoke, KL member. Hobbies, passions, interests... 9:30am in the 6:30 The Eddy Dean Show, A Month synopsis book in the Lobby to the list goes on for endless possibilities "Fountains Blue" for Day! see what the movie is about to be involved! Your Convenience. each day. Living Room Movie: Nicholas Nickleby 1 Groundhog Day 9:30 Music & Movement, AR 9:30 Cardio Drumming, AR 9:30 Meditation Moments, AR 9:30 Walk to the Dock, D National Wear Red Day 9:30 Seated Aerobics, AR Super Bowl LIV 10:30 Memoirs, Journaling, and 10:30 Decorating Party, KL 10:30 Twister with a Twist, KL 10:30 Pet Therapy with Lucy, AR 9:30 Balloon Volleyball, AR 10:00 Line Dancing with Mary Jane, A 10:00 Nondenominational Service, A Storytelling, KL 12:00 Men's Club, F 1:30 Unpopular Delicacies, AR 11:00 Introduction to Bridge, A 9:30 McGough Nature Park, O 10:30 Remembering Going to the 10:30 Well-Grounded, AR 1:30 Pink Crinkles, AR 1:30 -

WHITE SAVIOR in MELFI's HIDDEN FIGURES a THESIS in Partial

WHITE SAVIOR IN MELFI’S HIDDEN FIGURES A THESIS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for For S-1 Degree in American Studies in English Department Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Erinda Wanti 13020114190092 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2018 PRONOUNCEMENT The writer honestly confirms that she compiles this thesis entitled “White Savior in Melfi’s Hidden Figures” by herself and without taking any results from other researchers in S-1, S-2, S-3 and in diploma degree of any university. The writer ascertains also that she does not quote any material from other publications or someone’s paper except from the references mentioned. Semarang, July 6th 2018 Erinda Wanti MOTTO AND DEDICATION If you can dream it you can do it Walt Disney If something is destined for you never in a million years will it be for someone else Al Hadith The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well. Ralph Waldo Emerson I, with all my heart, dedicated this thesis to myself, who has been doing great all the time, my parents, who pour me with their love, and my friends, who push me back up when I was at my lowest stage. APPROVAL WHITE SAVIOR IN MELFI’S HIDDEN FIGURES Written by: Erinda Wanti 13020114190092 is approved by Thesis Advisor on July 6th, 2018 Thesis Advisor, Rifka Pratama, S.Hum., M.A. NPPU.H.7. 199004282018071001 The Head of the English Department, Dr. -

Wednesday Family Friendly Movie Nights with Clarke County Historical

INCLUDED IN THIS ISSUE • Presidents Welcome • Summer Movie Nights • The Galleries at Long Branch • Event Schedule • Long Branch Weddings • Horse Retirement Program June – July 2021 Hours of Operation: Grounds: Sunrise to Sunset Daily Wednesday Family Friendly (Complimentary) House: Monday to Friday 10am – 4pm Movie Nights with Clarke County Saturday & Sunday 12 – 4pm Historical Association (By Donation) President’sWelcome Wednesday June 30: Bristle Lip/Rapunzel/The Goose Girl On Behalf of the Board of Directors and Staff, welcome to Long Branch Historic House & Farm. Wednesday July 7: We are pleased to announce that Long Branch is National Treasure offering a full schedule of events for the entire family to enjoy in late Spring and Summer – A Wednesday July 14: Contemporary Art Exhibit in the East & West Secretariat Galleries, Tuesday Night Bridge and Wednesday Night Movies. The full schedule of which is now available for you to view online, on our website Wednesday July 21: calendar: www.visitlongbranch.org/events/ Night at the Museum Our historic house and grounds are available to Wednesday July 28: rent for private celebrations, ceremonies and Hidden Figures meetings as well, with a great four hour special rate still on-going. Please call the office for more details. Please also feel free to stop by the house Free Admission/Donations Welcome and property, to explore on your own, or with a Grounds Open @ 7:30/Movies Begin at Dark guided tour hosted by Colette Poisson on Saturdays Seating on the Lawn – Bring Your Own Chair/Blanket and Sundays from 12 -4pm. Snacks/Food/Beverages for Sale by Shenandoah Valley Golf Club We look forward to seeing you soon! Please refrain from using breakables or glassware. -

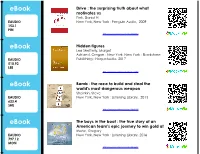

Ebook Ebook Ebook Ebook

eBook Drive : the surprising truth about what motivates us Pink, Daniel H EAUDIO New York, New York : Penguin Audio, 2009 153.1 PIN http://www.mackinvia.com/3443250 eBook Hidden figures Lee Shetterly, Margot Ashland, Oregon : New York, New York : Blackstone EAUDIO Publishing ; HarperAudio, 2017 510.92 LEE http://www.mackinvia.com/4115399 eBook Bomb : the race to build and steal the world's most dangerous weapon Sheinkin, Steve EAUDIO New York, New York : Listening Library, 2013 623.4 SHE http://www.mackinvia.com/3440728 eBook The boys in the boat : the true story of an American team's epic journey to win gold at Mone, Gregory EAUDIO New York, New York : Listening Library, 2016 797.12 MON http://www.mackinvia.com/3846682 Hamlet Shakespeare, William London, England : BBC Audio, 2017 EAUDIO 822.3 SHA http://www.mackinvia.com/5989897 This title is available as an eBook. eBook Use this QR code to check availability, or visit your MackinVIA account. You can also take this shelf card to the circulation desk to get assistance in checking out eBooks. EAUDIO 153.1 PENNSYLVANIA EBOOK CONSORTIUM PIN http://www.mackinvia.com/3443250 This title is available as an eBook. eBook Use this QR code to check availability, or visit your MackinVIA account. You can also take this shelf card to the circulation desk to get assistance in checking out eBooks. EAUDIO 510.92 PENNSYLVANIA EBOOK CONSORTIUM LEE http://www.mackinvia.com/4115399 This title is available as an eBook. eBook Use this QR code to check availability, or visit your MackinVIA account. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Official Newspaper of Rocky Hill Middle School Candace Whiting: A

Official Newspaper of Rocky Hill Middle School April 2017 Candace Whiting: A Role Model and Fighter By: Alyssa Bass and Marley Pinsky You may have heard of Mr. Stephen Whiting, the current princi- pal of Clarksburg High School - the school where the majority of our eighth graders will be attending next year. Mr. Whiting was previously a physical education teacher and then principal at Rocky Hill Middle School, but recently, he moved to Clarks- burg High School. But, someone you may not have heard of is Mr. Whiting’s spectacular daughter, Candace Whiting. Candace Candace Whiting is extremely versatile and has was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. She moved from Utah to Mar- many different hobbies. She plays several sports, yland just in time for her first birthday. She is now thirty-one such as skiing, gymnastics, golf, tennis, and swim- years old and lives in downtown Germantown. She attended ming, but her favorite sport is kayaking, which her elementary school in Montgomery County and then Frederick father inspired her to start. Candace is the fastest County, then was homeschooled throughout middle school and kayaker in the state of Maryland. Another one of her high school by her grandmother. Throughout school, her favor- passions is dancing. Candace has been dancing for ite subject was science. She graduated from high school when twenty-two years and does a variety of different she was nineteen. Candace Whiting is a public speaker who dance styles, such as tap, jazz, hip-hop, and ballet. has recently visited Rocky Hill to talk to students about her Candace is also passionate about reading.