The Birth of Agriculture During the Neolithic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

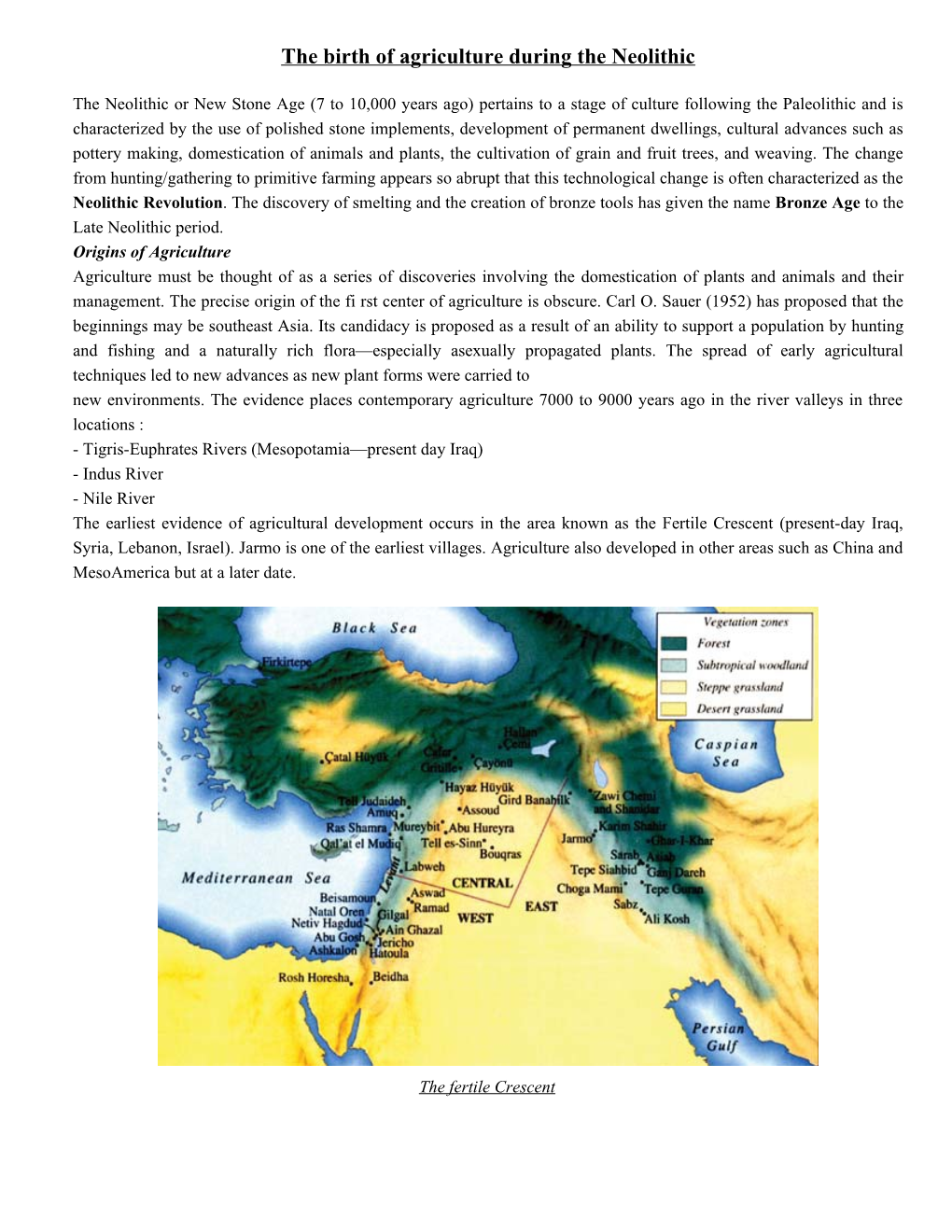

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Diachronic Size Variation in Prehistoric Central Asian Cereal Grains

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.633634 Interpreting Diachronic Size Variation in Prehistoric Central Asian Cereal Grains Giedre Motuzaite Matuzeviciute 1, Basira Mir-Makhamad 1,2* and Robert N. Spengler III 2 1 Department of Archaeology, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2 Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany The morphology of ancient cereal grains in Central Asia has been heavily discussed as an indicator of specific genetic variants, which are often linked to cultural factors or distinct routes of dispersal. In this paper, we present the largest currently existing database of barley (n = 631) and wheat (n = 349) measurements from Central Asia, obtained from two different periods at the Chap site (ca. 3,500 to 1,000 BC), located in the Tien Shan Mountains of Kyrgyzstan at 2,000 masl. The site is situated at the highest elevation ecocline for successful cereal cultivation and is, therefore, highly susceptible to minor climatic fluctuations that could force gradients up or down in the foothills. We contrast the Chap data with measurements from other second and first millennia BC sites in Edited by: the region. An evident increase in average size over time is likely due to the evolution Gianluca Piovesan, of larger grains or the introduction of larger variants from elsewhere. Additionally, site- or University of Tuscia, Italy region-specific variation is noted, and we discuss potential influences for the formation of Reviewed by: Anna Maria Mercuri, genetic varieties, including possible pleiotropic linkages and/or developmental responses University of Modena and Reggio to external factors, such as environmental fluctuations, climate, irrigation inputs, soil Emilia, Italy Mark Nesbitt, nutrients, pathologies, and seasonality. -

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

Tell Abu Suwwan, a Neolithic Site in Jordan: Preliminary Report on the 2005 and 2006 Field Seasons

Tell Abu Suwwan, A Neolithic Site in Jordan: Preliminary Report on the 2005 and 2006 Field Seasons Maysoon al-Nahar Department of Archaeology Institute of Archaeology University of Jordan Amman 11942, Jordan [email protected] Tell Abu Suwwan is the only Neolithic site excavated north of the Zarqa River in Jordan. Its architectural characteristics and the diagnostic lithic artifacts discovered at the site during the University of Jordan 2005 and 2006 field seasons, directed by the author, suggest that the site was occupied continually from the Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic Phase B (MPPNB) to the Yarmoukian (Pottery Neolithic) period. The site was divided by the excavator into two areas—A and B. Area A yielded a few walls, plaster floors, and orange clay. Area B yielded a large square or rectangular building with three clear types of plaster floors and an orange clay area. Both Areas A and B include numerous lithics, bones, and some small finds. Based on a recent survey outward from the excavated area, the probable size of Abu Suwwan is 10.5 ha (26 acres), and it contains complex architecture with a long chronological sequence. These attributes suggest that Tell Abu Suwwan is one of the Jordanian Neolithic megasites. introduction though the site contains a distinctive architecture, it shares various similarities with several other Levan- ell Abu Suwwan is a large Neolithic site in tine Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) sites, e.g., Jericho T north Jordan; it is on the east side of the old (Kenyon 1956: 69–77; 1969), Tell Ramad (de Con- Jarash–Amman highway, immediately before tenson 1971: 278–85), Tell Abu Hureyra (Moore, the turn west to Ajlun (fig. -

Did Anatolia Contribute to the Neolithization of Southeast Europe?*

Colloquium Anatolicum IV 2005 17-41 Did Anatolia contribute to the Neolithization of Southeast Europe?* Jak Yakar In the Near East, the process of “Neolithization” highlighted by sedenta- rization or semi-sedentarization could be defined as a slow socio-economic course that evolved parallel to the climatic amelioration with milder temper- atures and increased humidity during the early Holocene. Climatic changes having a certain impact on the local flora would have affected the composi- tion of the local fauna. Shifting migration patterns and feeding zones of animal species hunted for their meat due to environmental changes no doubt neces- sitated certain economic adaptations requiring lesser or more selective mobil- ity on the part of hunter-gatherer communities. Recognizing the archaeologi- cal implications of social changes during the process of sedentarization is a difficult task, in most instances attainable only by way of an interdisciplinary approach. In Anatolia, the chronological sequence of this process indicates an early start in the southeast, gradually spreading to areas of grassland vege- tation in the southern Anatolian plateau. It subsequently reached the Aegean coast and slightly later spread to the more northerly regions of western Anatolia. The question is did the spread of this so-called “Neolithization” involve human agents from a specific geographic source area? Most scholars answer this question in the affirmative despite the fact that ethno-culturally the Neo- lithic society of Anatolia was not a homogenous entity. The society in this sub-continent characterized by its geographical diversity was equally divers ethno-culturally; in certain peripheral habitats having more in common with the prehistoric inhabitants of neighboring lands (e.g. -

Driving Dispossession

DRIVING DISPOSSESSION THE GLOBAL PUSH TO “UNLOCK THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF LAND” DRIVING DISPOSSESSION THE GLOBAL PUSH TO “UNLOCK THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF LAND” Acknowledgements Authors: Frédéric Mousseau, Andy Currier, Elizabeth Fraser, and Jessie Green, with research assistance by Naomi Maisel and Elena Teare. We are deeply grateful to the many individual and foundation donors who make our work possible. Thank you. Views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Design: Amymade Graphic Design, [email protected], amymade.com Cover Photo: Maungdaw, Myanmar - Farm laborers and livestocks are seen in a paddy field in Warcha village April 2016 © FAO / Hkun La Photo page 7: Wheat fields © International Finance Corporation Photo page 10: USAID project mapping and titling land in Petauke, Zambia in July 2018 ©Sandra Coburn Photo page 13: Lettuce harvest © Carsten ten Brink Photo page 16: A bull dozer flattens the earth after forests have been cleared in West Pomio © Paul Hilton / Greenpeace Photo page 21: Paddy fields © The Oakland Institute Photo page 24: Forest Fires in Altamira, Pará, Amazon in August, 2019 © Victor Moriyama / Greenpeace Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). You are free to share, copy, distribute, and transmit this work under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work to the Oakland Institute and its authors. -

Ch. 4. NEOLITHIC PERIOD in JORDAN 25 4.1

Borsa di studio finanziata da: Ministero degli Affari Esteri di Italia Thanks all …………. I will be glad to give my theses with all my love to my father and mother, all my brothers for their helps since I came to Italy until I got this degree. I am glad because I am one of Dr. Ursula Thun Hohenstein students. I would like to thanks her to her help and support during my research. I would like to thanks Dr.. Maysoon AlNahar and the Museum of the University of Jordan stuff for their help during my work in Jordan. I would like to thank all of Prof. Perreto Carlo and Prof. Benedetto Sala, Dr. Arzarello Marta and all my professors in the University of Ferrara for their support and help during my Phd Research. During my study in Italy I met a lot of friends and specially my colleges in the University of Ferrara. I would like to thanks all for their help and support during these years. Finally I would like to thanks the Minister of Fournier of Italy, Embassy of Italy in Jordan and the University of Ferrara institute for higher studies (IUSS) to fund my PhD research. CONTENTS Ch. 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Ch. 2. AIMS OF THE RESEARCH 3 Ch. 3. NEOLITHIC PERIOD IN NEAR EAST 5 3.1. Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) in Near east 5 3.2. Pre-pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) in Near east 10 3.2.A. Early PPNB 10 3.2.B. Middle PPNB 13 3.2.C. Late PPNB 15 3.3. -

The Macrobotanical Evidence for Vegetation in the Near East, C. 18 000/16 000 B.C to 4 000 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 1997 The Macrobotanical Evidence for Vegetation in the Near East, c. 18 000/16 000 B.C to 4 000 B.C. Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Miller, N. F. (1997). The Macrobotanical Evidence for Vegetation in the Near East, c. 18 000/16 000 B.C to 4 000 B.C.. Paléorient, 23 (2), 197-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/paleo.1997.4661 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/36 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Macrobotanical Evidence for Vegetation in the Near East, c. 18 000/16 000 B.C to 4 000 B.C. Abstract Vegetation during the glacial period, post-glacial warming and the Younger Dryas does not seem to have been affected by human activities to any appreciable extent. Forest expansion at the beginning of the Holocene occurred independently of human agency, though early Neolithic farmers were able to take advantage of improved climatic conditions. Absence of macrobotanical remains precludes discussion of possible drought from 6,000 to 5,500 ВС. By farming, herding, and fuel-cutting, human populations began to have an impact on the landscape at different times and places. Deleterious effects of these activities became evident in the Tigris-Euphrates drainage during the third millennium ВС based on macrobotanical evidence from archaeological sites. -

A New Strategy for Utilizing Rice Forage Production Using a No-Tillage System to Enhance the Self-Sufficient Feed Ratio of Small Scale Dairy Farming in Japan

Sustainability 2014, 6, 4975-4989; doi:10.3390/su6084975 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article A New Strategy for Utilizing Rice Forage Production Using a No-Tillage System to Enhance the Self-Sufficient Feed Ratio of Small Scale Dairy Farming in Japan Windi Al Zahra 1, Takeshi Yasue 2, Naomi Asagi 2, Yuji Miyaguchi 2, Bagus Priyo Purwanto 1 and Masakazu Komatsuzaki 3,* 1 Faculty of Animal Sciences, Bogor Agricultural University, Jl. Raya Darmaga Kampus IPB Darmaga Bogor, West Java 16680, Indonesia 2 College of Agriculture, Ibaraki University, 3-21-1 Ami, Ibaraki 300-0393, Japan 3 Center for Field Science Research and Education, Ibaraki University, 3-21-1 Ami, Ibaraki 300-0393, Japan * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +81-29-888-8707. Received: 19 March 2014; in revised form: 21 July 2014 / Accepted: 21 July 2014 / Published: 6 August 2014 Abstract: Rice forage systems can increase the land use efficiency in paddy fields, improve the self-sufficient feed ratio, and provide environmental benefits for agro-ecosystems. This system often decreased economic benefits compared with those through imported commercial forage feed, particularly in Japan. We observed the productivities of winter forage after rice harvest between conventional tillage (CT) and no-tillage (NT) in a field experiment. An on-farm evaluation was performed to determine the self-sufficient ratio of feed and forage production costs based on farm evaluation of the dairy farmer and the rice grower, who adopted a rice forage system. The field experiment detected no significant difference in forage production and quality between CT and NT after rice harvest. -

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bar-Yosef, Ofer. 1998. “On the Nature of Transitions: The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution.” Cam. Arch. Jnl 8 (02) (October): 141. Published Version doi:10.1017/S0959774300000986 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12211496 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8:2 (1998), 141-63 On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution Ofer Bar-Yosef This article discusses two major revolutions in the history of humankind, namely, the Neolithic and the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic revolutions. The course of the first one is used as a general analogy to study the second, and the older one. This approach puts aside the issue of biological differences among the human fossils, and concentrates solely on the cultural and technological innovations. It also demonstrates that issues that are common- place to the study of the trajisition from foraging to cultivation and animal husbandry can be employed as an overarching model for the study of the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on the core areas where each of these revolutions began, the ensuing dispersals and their geographic contexts. -

Opening up the South

Hungry Corporations: CO EXUS E N Transnational Biotech Companies Colonise the Food Chain By Helena Paul and Ricarda Steinbrecher with Devlin Kuyek and Lucy Michaels www.econexus.info In association with Econexus and Pesticide Action Network, Asia-Pacific [email protected] Published by Zed Books, November 2003 Chapter 8: Opening Up the South The end is control. To properly understand the means one must first understand the end. A farmer who doesn’t borrow money and plants his own seed is difficult to control because he can feed himself and his neighbours. He doesn’t have to depend on a banker or a politician in a distant city. While farmers in America today are little more than tenants serving corporate and banking interests, the rural Third World farmer has remained relatively out of the loop – until now.1 As the tables that follow show clearly, most GM crops total commercial seed sales of $30 billion for 2001 (see to date have been planted in the North, primarily the Chapter 4), they are also the biggest seed players. US. Argentina is the only country in the South that In order to progress, the companies are looking for grows them on a large scale; GM soya has been grown allies and networks they can use, such as the CNFA there since 1996. China is growing Bt cotton (see pp. 126–9). It is also important to influence the commercially, and a comparatively small amount of governments and institutions (such as universities and tobacco. However, the push into the South is beginning extension services) of countries in the global South, so to accelerate. -

An Organic Khorasan Wheat-Based Replacement Diet Improves Risk Profile of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: a Randomized Crossover Trial

Nutrients 2015, 7, 3401-3415; doi:10.3390/nu7053401 OPEN ACCESS nutrients ISSN 2072-6643 www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients Article An Organic Khorasan Wheat-Based Replacement Diet Improves Risk Profile of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Randomized Crossover Trial Anne Whittaker 1, Francesco Sofi 2,3,4,*, Maria Luisa Eliana Luisi 4, Elena Rafanelli 4, Claudia Fiorillo 5, Matteo Becatti 5, Rosanna Abbate 3, Alessandro Casini 2, Gian Franco Gensini 3 and Stefano Benedettelli 1 1 Department of Agrifood Production and Environmental Sciences, University of Florence, Piazzale delle Cascine 18, 50144 Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (S.B.) 2 Unit of Clinical Nutrition, Careggi University Hospital, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134 Florence, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134, Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (G.F.G.) 4 Don Carlo Gnocchi Foundation Florence, Via di Scandicci 269, 50143, Florence, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.L.L.); [email protected] (E.R.) 5 Department of Clinical and Experimental Biomedical Sciences, Interdipartimental Center for Research on Food and Nutrition, University of Florence, Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, 50019, Italy; E-Mails: [email protected] (C.F.); [email protected] (M.B.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-055-7949420; Fax: +39-055-7949418. Received: 20 November 2014 / Accepted: 21 April 2015 / Published: 11 May 2015 Abstract: Khorasan wheat is an ancient grain with previously reported health benefits in clinically healthy subjects. -

Domestication and Early Agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, Diffusion, and Impact

PERSPECTIVE Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact Melinda A. Zeder* Archaeobiology Program, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013 Edited by Jeremy A. Sabloff, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA, and approved May 27, 2008 (received for review March 20, 2008) The past decade has witnessed a quantum leap in our understanding of the origins, diffusion, and impact of early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin. In large measure these advances are attributable to new methods for documenting domestication in plants and animals. The initial steps toward plant and animal domestication in the Eastern Mediterranean can now be pushed back to the 12th millennium cal B.P. Evidence for herd management and crop cultivation appears at least 1,000 years earlier than the morphological changes traditionally used to document domestication. Different species seem to have been domesticated in different parts of the Fertile Crescent, with genetic analyses detecting multiple domestic lineages for each species. Recent evidence suggests that the ex- pansion of domesticates and agricultural economies across the Mediterranean was accomplished by several waves of seafaring colonists who established coastal farming enclaves around the Mediterranean Basin. This process also involved the adoption of do- mesticates and domestic technologies by indigenous populations and the local domestication of some endemic species. Human envi- ronmental impacts are seen in the complete replacement of endemic island faunas by imported mainland fauna and in today’s anthropogenic, but threatened, Mediterranean landscapes where sustainable agricultural practices have helped maintain high bio- diversity since the Neolithic.