The Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qarawat Bani Hassan Town Profile

Qarawat Bani Hassan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2013 Palestinian Localities Study Salfit Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Salfit Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Salfit Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Salfit Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Salfit Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Salfit Governorate. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 28, Issue 3 2004 Article 10 Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists – How the International Court of Justice’s Ruling in The Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Made the World Safer for Terrorists and More Dangerous for Member States of the United Nations Rebecca Kahan∗ ∗ Copyright c 2004 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Building a Protective Wall Around Terrorists – How the International Court of Justice’s Ruling in The Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Made the World Safer for Terrorists and More Dangerous for Member States of the United Nations Rebecca Kahan Abstract Part I of this Note will examine two recent actions in the war against international terror- ism: the Israeli plan to build a separation barrier between Israel and the OPT, and the invasion of Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. Part II will discuss two important deviations by the ICJ from past interpretation of international law that were announced in the advisory proceed- ings against Israel: a new elucidation by the ICJ regarding principles of judicial propriety and a new analysis of the abilities of States to act in self-defense under Article 51 of the U.N. Charter. Part III will address the impact on the international community’s fight against terrorism, and the role of the ICJ as an international entity. BUILDING A PROTECTIVE WALL AROUND TERRORISTS HOW THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE'S RULING IN THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF A WALL IN THE OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY MADE THE WORLD SAFER FOR TERRORISTS AND MORE DANGEROUS FOR MEMBER STATES OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rebecca Kahan* INTRODUCTION The nature of the threats posed to States has changed since the adoption of the U.N. -

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates Umm Dar Terminals ’AkkabaDhaher al ’Abed Zabda Agricultural Gate (gap in the Wall) Controlled access through the Wall has been promised by the GOI to Ya’bad Wall (being finalised or complete) Masqufet al Hajj Mas’ud enable movement between Israel and the West Bank for Palestinian West Bank boundary/Green Line (estimate) Qaffin Imreiha populations who are either trapped in enclaves or isolated from their Road network agricultural lands. Palestinian Locality Hermesh Israeli Settlement Nazlat ’Isa An Nazla al Wusta According to Israel's State Attorney's office, five controlled crossings or NOTE: Agricultural Gate locations have been Baqa ash Sharqiya collected from field visits by OCHA staff and An Nazla ash Sharqiya terminals similar to the Erez terminal in northern Gaza will be built along information partners. The Wall trajectory is based on satellite imagery and field visits. An Nazla al Gharbiya the Wall. The Government of Israel recently decided that the Israeli Airport Authority will plan and operate the terminals. One of the main terminals between Israel and the West Bank appears to be being built Zeita Seida near Taibeh, 75 acres (300 dunums)35 in a part of Tulkarm City 36 Kafr Ra’i considered area A. ’Attil ’Illar The remaining terminals/control points are designated for areas near Jenin, Atarot north of Jerusalem, north of the Gush Etzion and near Deir al Ghusun Tarkumiyeh settlement bloc. Al Jarushiya Bal’a Agricultural Crossings and Gates Iktaba Al ’Attara The State Attorney's Office has stated that 26 agricultural gates will be TulkarmNur Shams Camp established along the length of the Wall to allow Palestinian farmers who Kafr Rumman have land west of the Wall, to cross. -

Arcview Print

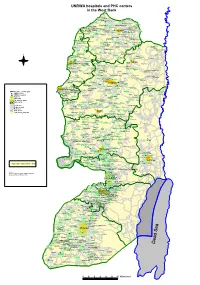

UNRWA hospitals and PHC centers in the West Bank Zububa Rummana At Tayba (Jenin)Ti'innik As Sa'aida 'Arrabuna Silat al Harithiya Al Jalama 'Anin ÚÊ 'Arrana Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Khirbet SuruAjl Yamun Dahiyat Sabah al Kheir Umm ar Rihan Barghasha Kafr Dan Khirbet 'Abdallah aDl hYauhneisr al Malih Mashru' Beit Qad Barta'a ash SharqiyaTura al Gharbiya Al 'Araqa Al Jameela Beit Qad Khirbet al Muntar al Gharbiya Al Hashimiya ÚÊ Umm Qabub At Tarem Jenin Camp Jalbun Khirbet MUasm'umd Dar Kafr Qud Jenin 'Aba Birqin Wad ad DaDbei'ir Abu Da'if 'Akkaba QeiqisZabda ÚÊ Ya'bad Kufeirit 'Arab as Suweitat Khirbet Sab'ein Qaffin Imreiha Ash Shuhada Umm at Tut Jalqamus Bir al Basha Al Mughayyir (Jenin) Nazlat 'Isa Tannin Baqa Ash ShAanr qNiyaazla ash Sharqiya Arraba Ad Damayra Qabatiya Khirbet Marah ar Raha An Nazla al Gharbiya Telfit Wadi Du'oq Khirbet Kharruba Al MansMuiraka Fahma al Jadida Zeita Seida Al Jarba Misliya Az Zababida Raba Bardala Fahma Kardala Kafr Ra'i Az Zawiya (Jenin) Ibziq Al Kufeir Ein el Beida 'Attil 'Illar 'Ajja Sir 'Anza Sanur Deir al Ghusun Ar Rama Mantiqat al Heish Salhab N Meithalun 'Aqqaba Al Farisiya Al Jarushiya Tayasir Al 'Aqaba Masqufet al Hajj Mas'ud Al Jadida Bal'a Al 'Asa'asa Ath Thaghra Al Malih Al 'Attara Siris Iktaba ÚÊ Jaba' (Jenin) ÚÊ CaÚÊmp Tulkarm Kafr Rumman Silat adh Dhahr Dhinnaba Tubas 'Izbat Abu Khameis Kashda 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza Tulkarm 'Izbat al Khilal Khirbet at Tayyah Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid ÚÊ Kafa Al Hafasa Beit Imrin El Far'a Camp Far'un'Izbat Shufa Ramin Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil -

Occupied Palestinian Territory (Including East Jerusalem)

Reporting period: 29 March - 4 April 2016 Weekly Highlights For the first week in almost six months there have been no Palestinian nor Israeli fatalities recorded. 88 Palestinians, including 18 children, were injured by Israeli forces across the oPt. The majority of injuries (76 per cent) were recorded during demonstrations marking ‘Land Day’ on 30 March, including six injured next to the perimeter fence in the Gaza Strip, followed by search and arrest operations. The latter included raids in Azzun ‘Atma (Qalqiliya) and Ya’bad (Jenin) involving property damage and the confiscation of two vehicles, and a forced entry into a school in Ras Al Amud in East Jerusalem. On 30 occasions, Israeli forces opened fire in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) at land and sea in Gaza, injuring two Palestinians as far as 350 meters from the fence. Additionally, Israeli naval forces shelled a fishing boat west of Rafah city, destroying it completely. Israeli forces continued to ban the passage of Palestinian males between 15 and 25 years old through two checkpoints controlling access to the H2 area of Hebron city. This comes in addition to other severe restrictions on Palestinian access to this area in place since October 2015. During the reporting period, Israeli forces removed the restrictions imposed last week on Beit Fajjar village (Bethlehem), which prevented most residents from exiting and entering the village. This came following a Palestinian attack on Israeli soldiers near Salfit, during which the suspected perpetrators were killed. Israeli forces also opened the western entrance to Hebron city, which connects to road 35 and to the commercial checkpoint of Tarqumiya. -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

Joint Services Council Solid Waste Management Project Jenin

Joint Services Council for Solid Waste Management Project In 1998 a comprehensive approach to improving waste management services in the West Bank was initiated under the Solid Waste and Environmental Management – Project ( Swemp) in Palestine. Joint Services Council for Solid Waste Management z A quasi–governmental and regional entity established in accordance with the Local Government Law. z The JSC is managed by a Board that consists of 20 local Authorities (15 municipalities and 5 village councils). Fulfillment of the Credit Agreement Conditions - The on-lending agreement between the Ministry of Finance and the JSC was signed; - The land was secured through purchase or long term lease by the JSC; - The PIU was established & became the executive branch of the JSC; - A Deposit Account was created (US$63,000 from the local authorities); - A tariff for waste collection and disposal was set and adopted by the local authorities. JSC Mission Statement is: z To provide an organized and effective SWM service; z To seek long-term sustainability of service by building technical capacities at local authorities; z To raise public awareness and promote effective public participation; z To comply with pertinent laws and regulations prevailing in Palestine. The Project z Components: Construct a sanitary landfill; Closing and rehabilitation random dumpsites and eliminate waste burning; and Improve Access to the new site; z Cost: US$14 million (US$9 million Credit from World Bank + US$3.75 million from the EU + US$1.25 million contribution from the local authorities). Zahrat Al Finjan Landfill Location Dumpsites Before Rehabilitation Dumpsite During Rehabilitation: Dumpsite After Rehabilitation ZF Landfill Project The Area : the purchased land is 240,000 m2, the area of the cells which are ready to be used is 90000 m2, the cells are going to serve the northern governorates for about 15 years during the first stage , than the cells will be extended in the remaining land owned by the council. -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

Ground to a Halt, Denial of Palestinians' Freedom Of

Since the beginning of the second intifada, in September 2000, Israel has imposed restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in the West Bank that are unprecedented in scope and duration. As a result, Palestinian freedom of movement, which was limited in any event, has turned from a fundamental human right to a privilege that Israel grants or withholds as it deems fit. The restrictions have made traveling from one section to another an exceptional occurrence, subject to various conditions and a showing of justification for the journey. Almost every trip in the West Bank entails a great loss of time, much uncertainty, friction with soldiers, and often substantial additional expense. The restrictions on movement that Israel has imposed on Palestinians in the West Bank have split the West Bank into six major geographical units: North, Central, South, the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea, the enclaves resulting from the Separation Barrier, and East Jerusalem. In addition to the restrictions on movement from area to area, Israel also severely restricts movement within each area by splitting them up into subsections, and by controlling and limiting movement between them. This geographic division of the West Bank greatly affects every aspect of Palestinian life. B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories Ground to a Halt 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 Denial of Palestinians’ Freedom Tel. (972) 2-6735599 Fax. (972) 2-6749111 of Movement in the West Bank www.btselem.org • [email protected] August 2007 Ground to a Halt Denial of Palestinians’ Freedom of Movement in the West Bank August 2007 Stolen land is concrete, so here and there calls are heard to stop the building in settlements and not to expropriate land. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I T E D N A T I O N S N A T I O N S U N I E S OCHA Weekly Report: 4 – 10 July 2007 | 1 OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 4 – 10 July 2007 Of note this week Gaza Strip: • The IDF killed 11 Palestinians, injured 15, and arrested 70 during its incursion into the area southeast of Al Bureij Camp (Central Gaza). In addition, three Palestinians were injured, including a 15-year-old boy, during IDF military operations southeast of Beit Hanoun. • A total of 23 Qassam rockets and 33 mortar shells were fired from Gaza towards Israel, of which at least four rockets and 29 mortar shells targeted Kerem Shalom crossing. Five rockets landed in the Palestinian area. Hamas and Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility. No injuries were reported. • The Palestinian Ministry of Health confirmed that it has returned at least 25 corpses to Gaza via Kerem Shalom since the closure of Rafah until 5 July. In all cases, the persons had passed away in Egyptian or other overseas hospitals and not at the border. • Senior Palestinian traders were able to cross Erez crossing this week for the first time since 12 June. Humanitarian assistance continues to enter Gaza through Kerem Shalom and Sufa. Critical medical cases with special coordination arrangements exited through Erez. Karni was open on two days for the crossing of wheat and wheat grain.