Sinker Structure of Phoradendron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Communities & Habitats

Plant Communities & Habitats CLASS READINGS Key to Common Trees of Bouverie Preserve Bouverie Vegetation Map This class will be held Deciduous & Evergreen Oaks of Bouverie Preserve almost entirely on the trail so dress Sun Leaves & Shade Leaves accordingly and bring Characteristics of the Oaks of Bouverie Preserve plenty of water Chaparral & Fire (California’s Changing Landscapes, Michael Barbour et.al., 1993) Bouverie Preserve Chaparral (DeNevers) ACR Fire Ecology Program Mixed Evergreen Forest (California’s Changing Landscapes, Michael Barbour et.al., 1993) Ecological Tolerances of Riparian Plants (River Partners) Call of the Galls (Bay Nature Magazine, Ron Russo, 2009) Oak Galls of Bouverie Preserve Leaves of Three (Bay Nature Magazine, Eaton & Sullivan, 2013) Mistletoe – Magical, Mysterious, & Misunderstood (Wirka) How Old is This Twig (Wirka) CALNAT: California Naturalist Handbook Chapter 4 (98-109, 114-115) Chapter 5 (117-138) Key Concepts By the end of this class, we hope you will be able to: Use a simple key to identify trees at Bouverie Preserve, Look around you and determine whether you are in oak woodland, mixed evergreen forest, riparian woodland, or chaparral -- and get a “feel” for each, Define: Plant Community, Habitat, Ecotone; understand how to discuss/investigate each with students, Stand under a large oak and guide students in exploring/discovering the many species that live on/around it, Find a gall on an oak leaf or twig and get excited about the lifecycle of the critters who live inside, Explain how chaparral plants are fire-adapted and look for evidence of these adaptations, Locate at least one granary tree and notice acorn woodpeckers that are guarding it, List some of the animals that rely on Bouverie’s oak woodland habitat, and Make an acorn whistle & count the years a twig has been growing SEQUOIA CLUB Resources When one tugs at a In the Bouverie Library single thing in nature, he A Manual of California Vegetation, second edition, finds it attached to the John Sawyer and Todd Keeler‐ Wolf (2009). -

"Santalales (Including Mistletoes)"

Santalales (Including Introductory article Mistletoes) Article Contents . Introduction Daniel L Nickrent, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA . Taxonomy and Phylogenetics . Morphology, Life Cycle and Ecology . Biogeography of Mistletoes . Importance of Mistletoes Online posting date: 15th March 2011 Mistletoes are flowering plants in the sandalwood order that produce some of their own sugars via photosynthesis (Santalales) that parasitise tree branches. They evolved to holoparasites that do not photosynthesise. Holopar- five separate times in the order and are today represented asites are thus totally dependent on their host plant for by 88 genera and nearly 1600 species. Loranthaceae nutrients. Up until recently, all members of Santalales were considered hemiparasites. Molecular phylogenetic ana- (c. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (550 species) have the lyses have shown that the holoparasite family Balano- highest species diversity. In South America Misodendrum phoraceae is part of this order (Nickrent et al., 2005; (a parasite of Nothofagus) is the first to have evolved Barkman et al., 2007), however, its relationship to other the mistletoe habit ca. 80 million years ago. The family families is yet to be determined. See also: Nutrient Amphorogynaceae is of interest because some of its Acquisition, Assimilation and Utilization; Parasitism: the members are transitional between root and stem para- Variety of Parasites sites. Many mistletoes have developed mutualistic rela- The sandalwood order is of interest from the standpoint tionships with birds that act as both pollinators and seed of the evolution of parasitism because three early diverging dispersers. Although some mistletoes are serious patho- families (comprising 12 genera and 58 species) are auto- gens of forest and commercial trees (e.g. -

Interação Entre Aves Frugivoria E Espécies De Erva-De-Passarinho Em De Puxinanã E Campina Grande, Paraíba

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DA PARAÍBA CAMPUS I – CAMPINA GRANDE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS E DA SAÚDE CURSO DE GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS LAILSON DA SILVA ALVES INTERAÇÃO ENTRE AVES FRUGIVORIA E ESPÉCIES DE ERVA-DE-PASSARINHO EM DE PUXINANÃ E CAMPINA GRANDE, PARAÍBA CAMPINA GRANDE – PB 2011 F ICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELA BIBLIOTECA CENTRAL – UEPB A474i Alves, Lailson da Silva. Interação entre aves frugívora e espécies de erva-de-passarinho em Puxinanã e Campina Grande, Paraíba [manuscrito] / Lailson da Silva Alves. – 2011. 20 f. : il. Digitado. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Graduação em Biologia) – Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, 2011. “Orientação: Prof. Dr. Humberto Silva, Departamento de Biologia”. 1. Aves frugívoras. 2. Erva-de-passarinho. 3. Dispersão de sementes. I. Título. CDD 21. ed. 636.6 INTERAÇÃO ENTRE AVES FRUGIVORIA E ESPÉCIES DE ERVA-DE-PASSARINHO EM DE PUXINANÃ E CAMPINA GRANDE, PARAÍBA ALVES, Lailson da silva RESUMO A dispersão é um processo em que a regeneração natural das populações de plantas zoocóricas é fortemente dependente da avifauna. Uma das principais interações entre plantas e aves é a frugivoria, em que animais frugívoros colaboram na dispersão dos propágulos de diversas espécies de plantas. As ervas-de-passarinho, nome genérico dado a algumas plantas que apesar de terem ampla distribuição nos trópicos também se encontram associadas ao ambiente de caatinga, são assim chamadas devido à dispersão de suas sementes, nas quais seus frutos servem de alimentos para diversas aves e estas ao defecarem levam suas sementes a longas distâncias. São plantas hemiparasitas e devido a isto têm sua importância econômica associada aos prejuízos que causam a plantações. -

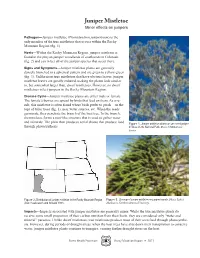

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Update on the Birds of Isla Guadalupe, Baja California

UPDATE ON THE BIRDS OF ISLA GUADALUPE, BAJA CALIFORNIA LORENZO QUINTANA-BARRIOS and GORGONIO RUIZ-CAMPOS, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Apartado Postal 1653, Ense- nada, Baja California, 22800, México (U. S. mailing address: PMB 064, P. O. Box 189003, Coronado, California 92178-9003; [email protected] PHILIP UNITT, San Diego Natural History Museum, P. O. Box 121390, San Diego, California 92112-1390; [email protected] RICHARD A. ERICKSON, LSA Associates, 20 Executive Park, Suite 200, Irvine, California 92614; [email protected] ABSTRACT: We report 56 bird specimens of 31 species taken on Isla Guadalupe, Baja California, between 1986 and 2004 and housed at the Colección Ornitológica del Laboratorio de Vertebrados de la Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada, along with other sight and specimen records. The speci- mens include the first published Guadalupe records for 10 species: the Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris), Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), Bonaparte’s Gull (Larus philadelphia), Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus cinerascens), Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus), Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor), Yellow Warbler (Dendroica petechia), Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia), Yellow-headed Blackbird (Xan- thocephalus xanthocephalus), and Orchard Oriole (Icterus spurius). A specimen of the eastern subspecies of Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater ater) and a sight record of the Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus) are the first reported from the Baja California Peninsula (and islands). A photographed Franklin’s Gull (Larus pipixcan) is also an island first. Currently 136 native species and three species intro- duced in North America have been recorded from the island and nearby waters. -

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts Oral Presentations Phylogenetic relationships in Phoradendron (Viscaceae) Vanessa Ashworth, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Keywords: Phoradendron, Systematics, Phylogenetics Phoradendron Nutt. is a genus of New World mistletoes comprising ca. 240 species distributed from the USA to Argentina and including the Antillean islands. Taxonomic treatments based on morphology have been hampered by phenotypic plasticity, size reduction of floral parts, and a shortage of taxonomically useful traits. Morphological characters used to differentiate species include the arrangement of flowers on an inflorescence segment (seriation) and the presence/absence and pattern of insertion of cataphylls on the stem. The only trait distinguishing Phoradendron from Dendrophthora Eichler, another New World mistletoe genus with a tropical distribution contained entirely within that of Phoradendron, is the number of anther locules. However, several lines of evidence suggest that neither Phoradendron nor Dendrophthora is monophyletic, although together they form the strongly supported monophyletic tribe Phoradendreae of nearly 360 species. To date, efforts to delineate supraspecific assemblages have been largely unsuccessful, and the only attempt to apply molecular sequence data dates back 16 years. Insights gleaned from that study, which used the ITS region and two partitions of the 26S nuclear rDNA, will be discussed, and new information pertinent to the systematics and biology of Phoradendron will be reviewed. The Viscaceae, why so successful? Clyde Calvin, University of California, Berkeley Carol A. Wilson, The University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California, Berkeley Keywords: Endophytic system, Epicortical roots, Epiparasite Mistletoe is the term used to describe aerial-branch parasites belonging to the order Santalales. -

Conspecific Pollen on Insects Visiting Female Flowers of Phoradendron Juniperinum (Viscaceae) in Western Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 4 Article 7 1-16-2017 Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona William D. Wiesenborn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Wiesenborn, William D. (2017) "Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(4), © 2017, pp. 478–486 CONSPECIFIC POLLEN ON INSECTS VISITING FEMALE FLOWERS OF PHORADENDRON JUNIPERINUM (VISCACEAE) IN WESTERN ARIZONA William D. Wiesenborn1 ABSTRACT.—Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) is a dioecious, parasitic plant of juniper trees ( Juniperus [Cupressaceae]) that occurs from eastern California to New Mexico and into northern Mexico. The species produces minute, spherical flowers during early summer. Dioecious flowering requires pollinating insects to carry pollen from male to female plants. I investigated the pollination of P. juniperinum parasitizing Juniperus osteosperma trees in the Cerbat Mountains in western Arizona during June–July 2016. I examined pollen from male flowers, aspirated insects from female flowers, counted conspecific pollen grains on insects, and estimated floral constancy from proportions of conspecific pollen in pollen loads. -

Effects of Mistletoe (Phoradendron Villosum)

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on June 20, 2018 Population ecology Effects of mistletoe (Phoradendron rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org villosum) on California oaks Walter D. Koenig1,2, Johannes M. H. Knops3, William J. Carmen4, Mario B. Pesendorfer1 and Janis L. Dickinson1 Research 1Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA 2 Cite this article: Koenig WD, Knops JMH, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA Carmen WJ, Pesendorfer MB, Dickinson JL. 4Carmen Ecological Consulting, 145 Eldridge Avenue, Mill Valley, CA 94941, USA 2018 Effects of mistletoe (Phoradendron WDK, 0000-0001-6207-1427 villosum) on California oaks. Biol. Lett. 14: 20180240. Mistletoes are a widespread group of plants often considered to be hemipar- http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0240 asitic, having detrimental effects on growth and survival of their hosts. We studied the effects of the Pacific mistletoe, Phoradendron villosum, a member of a largely autotrophic genus, on three species of deciduous California oaks. We found no effects of mistletoe presence on radial growth or survivorship Received: 7 April 2018 and detected a significant positive relationship between mistletoe and acorn Accepted: 31 May 2018 production. This latter result is potentially explained by the tendency of P. villosum to be present on larger trees growing in nitrogen-rich soils or, alternatively, by a preference for healthy, acorn-producing trees by birds that potentially disperse mistletoe. Our results indicate that the negative con- sequences of Phoradendron presence on their hosts are negligible—this Subject Areas: species resembles an epiphyte more than a parasite—and outweighed by ecology the important ecosystem services mistletoe provides. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Phainopepla Nestlings

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Phainopepla nestlings adjust begging behaviors to different male and female parental provisioning rules A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in Biology by Jeanne Marie Messier Committee in charge: Professor Sandra L. Vehrencamp, Chair Professor David S. Woodruff Professor Joshua R. Kohn Professor Trevor D. Price 2000 The Thesis of Jeanne Marie Messier is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2000 iii DEDICATION This Thesis is dedicated to Anne and John Messier, in memory of their daughter Jeanne. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature page........................................................................................................ iii Dedication.............................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents................................................................................................... v List of Figures........................................................................................................ vi List of Tables........................................................................................................ -

Epiparasitism in Phoradendron Durangense and P. Falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae) Clyde L. Calvin Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Carol A. Wilson Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Calvin, Clyde L. and Wilson, Carol A. (2009) "Epiparasitism in Phoradendron durangense and P. falcatum (Viscaceae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 27: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol27/iss1/2 Aliso, 27, pp. 1–12 ’ 2009, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden EPIPARASITISM IN PHORADENDRON DURANGENSE AND P. FALCATUM (VISCACEAE) CLYDE L. CALVIN1 AND CAROL A. WILSON1,2 1Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711-3157, USA 2Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Phoradendron, the largest mistletoe genus in the New World, extends from temperate North America to temperate South America. Most species are parasitic on terrestrial hosts, but a few occur only, or primarily, on other species of Phoradendron. We examined relationships among two obligate epiparasites, P. durangense and P. falcatum, and their parasitic hosts. Fruit and seed of both epiparasites were small compared to those of their parasitic hosts. Seed of epiparasites was established on parasitic-host stems, leaves, and inflorescences. Shoots developed from the plumular region or from buds on the holdfast or subjacent tissue. The developing endophytic system initially consisted of multiple separate strands that widened, merged, and often entirely displaced its parasitic host from the cambial cylinder. -

Radial Growth Rate Responses of Western Juniper (Juniperus Occidentalis Hook.) to Atmospheric and Climatic Changes: a Longitudinal Study from Central Oregon, USA

Article Radial Growth Rate Responses of Western Juniper (Juniperus occidentalis Hook.) to Atmospheric and Climatic Changes: A Longitudinal Study from Central Oregon, USA Peter T. Soulé 1,* and Paul A. Knapp 2 1 Appalachian Tree-Ring Laboratory, Department of Geography and Planning, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA 2 Carolina Tree-Ring Science Laboratory, Department of Geography, Environment, and Sustainability, University of North Carolina-Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27412, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2019; Accepted: 6 December 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: Research Highlights: In this longitudinal study, we explore the impacts of changing atmospheric composition and increasing aridity on the radial growth rates of western juniper (WJ; Juniperus occidentalis Hook). Since we sampled from study locations with minimal human agency, we can partially control for confounding influences on radial growth (e.g., grazing and logging) and better isolate the relationships between radial growth and climatic conditions. Background and Objectives: Our primary objective is to determine if carbon dioxide (CO2) enrichment continues to be a primary driving force for a tree species positively affected by increasing CO2 levels circa the late 1990s. Materials and Methods: We collected data from mature WJ trees on four minimally disturbed study sites in central Oregon and compared standardized radial growth rates to climatic conditions from 1905–2017 using correlation, moving-interval correlation, and regression techniques. Results: We found the primary climate driver of radial growth for WJ is antecedent moisture over a period of several months prior to and including the current growing season. Further, the moving-interval correlations revealed that these relationships are highly stable through time. -

35. ORCHIDACEAE/SCAPHYGLOTTIS 301 PSYGMORCHIS Dods

35. ORCHIDACEAE/SCAPHYGLOTTIS 301 PSYGMORCHIS Dods. & Dressl. each segment, usually only the uppermost persisting, linear, 5-25 cm long, 1.5-4.5 mm broad, obscurely emar- Psygmorchis pusilla (L.) Dods. & Dressl., Phytologia ginate at apex. Inflorescences single flowers or more com- 24:288. 1972 monly few-flowered fascicles or abbreviated, few-flowered Oncidium pusillum (L.) Reichb.f. racemes, borne at apex of stems; flowers white, 3.5-4.5 Dwarf epiphyte, to 8 cm tall; pseudobulbs lacking. Leaves mm long; sepals 3-4.5 mm long, 1-2 mm wide; petals as ± dense, spreading like a fan, equitant, ± linear, 2-6 cm long as sepals, 0.5-1 mm wide; lip 3.5-5 mm long, 2-3.5 long, to 1 cm wide. Inflorescences 1-6 from base of mm wide, entire or obscurely trilobate; column narrowly leaves, about equaling leaves, consisting of long scapes, winged. Fruits oblong-elliptic, ca 1 cm long (including the apices with several acute, strongly compressed, im- the long narrowly tapered base), ca 2 mm wide. Croat bricating sheaths; flowers produced in succession from 8079. axils of sheaths; flowers 2-2.5 cm long; sepals free, Common in the forest, usually high in trees. Flowers spreading, bright yellow, keeled and apiculate, the dorsal in the early dry season (December to March), especially sepal ca 5 mm long, nearly as wide, the lateral sepals in January and February. The fruits mature in the middle 4-5 mm long, 1-1.5 mm wide, hidden by lateral lobes to late dry season. of lip; petals to 8 mm long and 4 mm wide, bright yellow Confused with S.