Proceedings Ofthe Royal Air Force Historical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia

12/23/2018 Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia Special Operations Executive The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British World War II Special Operations Executive organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing Active 22 July 1940 – 15 secret organisations. Its purpose was to conduct espionage, sabotage and January 1946 reconnaissance in occupied Europe (and later, also in occupied Southeast Asia) Country United against the Axis powers, and to aid local resistance movements. Kingdom Allegiance Allies One of the organisations from which SOE was created was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret "stay-behind" resistance Role Espionage; organisation, which would have been activated in the event of a German irregular warfare invasion of Britain. (especially sabotage and Few people were aware of SOE's existence. Those who were part of it or liaised raiding operations); with it are sometimes referred to as the "Baker Street Irregulars", after the special location of its London headquarters. It was also known as "Churchill's Secret reconnaissance. Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". Its various branches, and Size Approximately sometimes the organisation as a whole, were concealed for security purposes 13,000 behind names such as the "Joint Technical Board" or the "Inter-Service Nickname(s) The Baker Street Research Bureau", or fictitious branches of the Air Ministry, Admiralty or War Irregulars Office. Churchill's Secret SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except Army where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal Allies (the United Ministry of States and the Soviet Union). -

The Magazine of RAF 100 Group Association

. The magazine of RAF 100 Group Association RAF 100 Group Association Chairman Roger Dobson: Tel: 01407 710384 RAF 100 Group Association Secretary Janine Bradley: Tel: 01723 512544 Email: [email protected] www.raf100groupassociation.org.uk Home to RAF 100 Group Association Memorabilia City of Norwich Aviation Museum Old Norwich Road, Horsham St Faith, Norwich, Norfolk NR10 3JF Telephone: 01603 893080 www.cnam.org.uk 2 Dearest Friends My heartfelt thanks to the kind and generous member who sent a gorgeous bouquet of flowers on one of my darkest days. Thank you so much! The card with them simply said: ‘ RAF 100 Group’ , and with the wealth of letters and cards which continue to arrive since the last magazine, I feel your love reaching across the miles. Thank you everyone for your support and encouragement during this difficult time. It has now passed the three month marker since reading that shocking email sent by Tony telling me he wasn’t coming home from London … ever ! I now know he has been leading a double life, and his relationship with another stretches back into the past. I have no idea what is truth and what is lies any more. To make it worse, they met up here in the north! There are times when I feel my heart can’t take any more … yet somehow, something happens to tell me I am still needed. My world has shrunk since I don’t have a car any more. Travel is restricted. But right here in Filey I now attend a Monday Lunch Club for my one hot meal of the week. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 46

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 46 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS OPENING ADDRESS – Air Chf Mshl Sir David Cousins 7 THE NORTHERN MEDITERRANEAN 1943-1945 by Wg 9 Cdr Andrew Brookes AIRBORNE FORCES IN THE NORTH MEDITERRANEAN 20 THEATRE OF OPERATIONS by Wg Cdr Colin Cummings DID ALLIED AIR INTERDICTION -

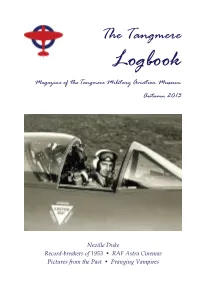

The Tangmere

The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2013 Neville Duke Record-breakers of 1953 • RAF Astra Cinemas Pictures from the Past • Pranging Vampires Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Trust Company Patron: The Duke of Richmond and Gordon Hon. President: Duncan Simpson, OBE Hon. Life Vice-President: Alan Bower Council of Trustees Chairman: Group Captain David Baron, OBE David Burleigh, MBE Reginald Byron David Coxon Dudley Hooley Ken Shepherd Phil Stokes Joyce Warren Officers of the Company Hon. Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Hon. Secretary: Joyce Warren Management Team Director: Dudley Hooley Curator: David Coxon General Manager and Chief Engineer: Phil Stokes Events Manager: David Burleigh, MBE Publicity Manager: Cherry Greveson Staffing Manager: Mike Wieland Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Shop Manager: Sheila Shepherd Registered in England and Wales as a Charity Charity Commission Registration Number 299327 Registered Office: Tangmere, near Chichester, West Sussex PO20 2ES, England Telephone: 01243 790090 Fax: 01243 789490 Website: www.tangmere-museum.org.uk E-mail: [email protected] 2 The Tangmere Logbook The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2013 The Record-breakers of 1953 4 Four World Air Speed Records are set in a remarkably busy year David Coxon Neville Duke as I Remember Him 8 An acquaintance with our late President David Baron Adventures of an RAF Cinema Projectionist 11 Chance encounters with Astra cinemas at home and abroad, and one with Ava Gardner Phil Dansie Pictures from My Father’s Album 19 . of some interesting historical moments Stan Hayter Operation Beef 23 How to provoke official displeasure by pranging yet another pampered Vampire Eric Mold From Our Archives . -

Air Navigation in the Service

A History of Navigation in the Royal Air Force RAF Historical Society Seminar at the RAF Museum, Hendon 21 October 1996 (Held jointly with The Royal Institute of Navigation and The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators) ii The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright ©1997: Royal Air Force Historical Society First Published in the UK in 1997 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 0 9519824 7 8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset and printed in Great Britain by Fotodirect Ltd, Brighton Royal Air Force Historical Society iii Contents Page 1 Welcome by RAFHS Chairman, AVM Nigel Baldwin 1 2 Introduction by Seminar Chairman, AM Sir John Curtiss 4 3 The Early Years by Mr David Page 66 4 Between the Wars by Flt Lt Alec Ayliffe 12 5 The Epic Flights by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford 34 6 The Second World War by Sqn Ldr Philip Saxon 52 7 Morning Discussions and Questions 63 8 The Aries Flights by Gp Capt David Broughton 73 9 Developments in the Early 1950s by AVM Jack Furner 92 10 From the ‘60s to the ‘80s by Air Cdre Norman Bonnor 98 11 The Present and the Future by Air Cdre Bill Tyack 107 12 Afternoon Discussions and -

Cecil James on the 1957 White Paper & Prof Horst

PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 4 – September 1988 Committee Members Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: B R Jutsum FCIS Membership Commander P O Montgomery Secretary: VRD and Bar, RNR Treasurer: A S Bennell MA BLitt Programme Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM Sub-Committee: *Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Air Commodore A G Hicks MA CEng MIERE MRAeS T C G James CMG MA Publications S Cox BA MA Sub Committee: A E F Richardson P G Rolfe ISO Members: *Group Captain M van der Veen MA CEng MIMechE MIEE MBIM *M A Fopp MA MBIM * ex-officio members 1 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned, and are not neces s arily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society or any member of the Committee. Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1988. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any form whatsoever is prohibited, without express written permission from the General Secretary of the Society. 2 CONTENTS Page 1. Future Programme 4 2. Editor’s Notes 5 3. The impact of the Sandys Defence Policy on the 9 RAF 4. Questions on Item 3 30 5. The Policy, Command and Direction of the 36 Luftwaffe in World War II 6. Questions on Item 5 56 7. Further Committee Member profiles 63 8. Minutes of the Annual General Meeting on 28 65 March 1988 3 FUTURE PROGRAMME All the following events will be held at the Royal Aeronautical Society, 4, Hamilton Place, London, W.1. -

Dropzone Issue 2

HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS V OLUME 6 I SSUE 2 THE DROPZONE J ULY 2008 Editor: John Harding Publisher: Fred West MOSQUITO BITES INSIDE THIS ISSUE: By former Carpetbagger Navigator, Marvin Edwards Flying the ‘Mossie’ 1 A wooden plane, a top-secret mission and my part in the fall of Nazi Germany I Know You 3 Firstly (from John Harding) a few de- compared to the B-24. While the B- tails about "The Wooden Wonder" - the 24’s engines emitted a deafening roar, De Havilland D.H.98 Mosquito. the Mossie’s two Rolls Royce engines Obituary 4 seemed to purr by comparison. Al- It flew for the first time on November though we had to wear oxygen masks Editorial 5 25th,1940, less than 11 months after due to the altitude of the Mossie’s the start of design work. It was the flight, we didn’t have to don the world's fastest operational aircraft, a heated suits and gloves that were Valencay 6 distinction it held for the next two and a standard for the B-24 flights. Despite half years. The prototype was built se- the deadly cold outside, heat piped in Blue on Blue 8 cretly in a small hangar at Salisbury from the engines kept the Mossie’s Hall near St.Albans in Hertfordshire cockpit at a comfortable temperature. Berlin Airlift where it is still in existence. 12 Only a handful of American pilots With its two Rolls Royce Merlin en- flew in the Mossie. Those who did had gines it was developed into a fighter some initial problems that required and fighter-bomber, a night fighter, a practice to correct. -

CERCLE AERONAUTIQUE LOUIS MOUILLARD PARACHUTAGES a LA RESISTANCE DANS LE RHÔNE Au Cours De La Seconde Guerre Mondiale, L

PARACHUTAGES A LA RESISTANCE DANS LE RHÔNE PARACHUTAGES A LA RESISTANCE DANS LE RHÔNE Au cours de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les opérations de parachutages d'agents ou d'armement à la Résistance française, ainsi qu'aux différents réseaux opérant en France, étaient organisées et planifiées par diverses organisations dépendant des Etats-Majors de Londres ou d'Alger, qui parfois étaient concurrents : les réseaux du Service Action (A,B,C,D,M,P et R) du Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action (BCRA) et de la Section RF du Special Organisation Executive (SOE) ; les réseaux dits Buckmaster de la Section F du Special Organisation Executive (SOE) ; les réseaux (Alliance, Confrérie Notre-Dame, Jade/Fitzoy, SR Air, etc...) dépendants du Secret Inteligence Service (SIS) britannique ; les Groupes Opérationnels (OG Antagonist, Emily, Justine, Percy Pink, Percy Red, etc...) et les réseaux américains (Jean, Penny, Farthing, Roy,WiWi, etc... ) de l'Office of Strategic Services (OSS) ; les missions interalliées (Cantinier, Citronnelle, Orgeat, Pectoral, Union, etc...) et les Plans Tripartrites (Jedburgh, Sussex, etc...) ; le réseau Service de Sécurité Militaire en France/Travaux Ruraux (SSMF/TR) du Colonel Rivet et du Commandant Paul Paillole. Chaque réseau avait sa propre organisation pour la réception des parachutages. Un même site de parachutage pouvait être utilisé par plusieurs réseaux avec un nom de code différent, ce qui a posé certains problèmes de coordination lors des opérations aériennes ou des avions venant d'Angleterre ont failli heurter des avions venus d'Alger et parachutant sur la même DZ. En ce qui concerne le BCRA dans le Rhône, nous retiendrons l'organisation suivante : : Raymond Fassin alias Sif est nommé par le BCRA, en novembre 1942, chef des opérations du Service des Opérations Aériennes et Maritimes (SOAM) pour les régions Région R1 (Lyon) et R2 (Marseille). -

(Without Amendment) By

The following article is provided (without amendment) by “Geograph Britain & Ireland” and can be seen at its website www.georgraphy.org.uk Heigham Holmes is indeed rumoured to have served as a Second World War landing ground used by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) but no evidence has to date been found to substantiate this rumour. The SOE was formed on 22nd July 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe and one of the organisation's best kept secrets were the night time activities involving 138 and 161 (Special) Squadrons of Bomber Command, RAF, flying SOE agents into occupied Europe by moonlight in their Lockheed A28 Hudsons, Short Stirlings, Halifaxes, Whitleys or Lysanders, the latter without doubt being the most famous aircraft involved in this secret work. In a publication titled 'Norfolk and Suffolk Airfields and Airstrips' (Part 6), authored by Huby Fairhead and published by the Norfolk & Suffolk Aviation Museum in June 1989, the author states that "From about 1940 to 1944 an RAF landing ground was located on the marshes known as Heigham Holmes. It appears all black Lysanders were detached here during this period while based at Newmarket or Tempsford, possibly for operations into the Low Countries". This appears to be the original (and only) source of information on which all later researchers have based theirs. The text also mentions a complex of farm buildings "to the east of a grass landing strip", the length of which is given as 6,000 yards (5,486 metres). This must surely be a mistake, considering that wartime RAF main runways were on average about 2000 yards (1,830 metres) long and secondary runways considerably shorter, and that Lysanders did not require a landing strip at all but could land on virtually any reasonably level ground and under conditions which would have defeated any other aircraft. -

HISTORY of WWII INFILTRATIONS INTO FRANCE-Rev62-06102013

Tentative of History of In/Exfiltrations into/from France during WWII from 1940 to 1945 (Parachutes, Plane & Sea Landings) Forewords This tentative of history of civilians and military agents (BCRA, Commandos, JEDBURGHS, OSS, SAS, SIS, SOE, SUSSEX/OSSEX, SUSSEX/BRISSEX & PROUST) infiltrated or exfiltrated during the WWII into France, by parachute, by plane landings and/or by sea landings. This document, which needs to be completed and corrected, has been prepared using the information available, not always reliable, on the following internet websites and books available: 1. The Order of the Liberation website : http://www.ordredelaliberation.fr/english/contenido1.php The Order of the Liberation is France's second national Order after the Legion of Honor, and was instituted by General De Gaulle, Leader of the "Français Libres" - the Free French movement - with Edict No. 7, signed in Brazzaville on November 16th, 1940. 2. History of Carpetbaggers (USAAF) partly available on Thomas Ensminger’s website addresses: ftp://www.801492.org/ (Need a user logging and password). It is not anymore possible to have access to this site since Thomas’ death on 03/05/2012. http://www.801492.org/MainMenu.htm http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Crewz.htm I was informed that Thomas Ensminger passed away on the 03/05/2012. I like to underline the huge work performed as historian by Thomas to keep alive the memory the Carpetbaggers’ history and their famous B24 painted in black. RIP Thomas. The USAAF Carpetbagger's mission was that of delivering supplies and agents to resistance groups in the enemy occupied Western European nations. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 41

1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 41 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2008 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain N Parton BSc (Hons) MA MDA MPhil CEng FRAeS RAF *Wing Commander A J C Walters BSc MA FRAeS RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS EDITOR’s NOTE 6 ERRATA 6 20 October 1986. THE INTELLIGENCE WAR AND THE 7 ROYAL AIR FORCE by Professor R V Jones CB CBE FRS. -

SOE in France: an Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France: 1940–1944

ii SOE IN FRANCE WHITEHALL HISTORIES: GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL HISTORY SERIES ISSN: 1474-8398 The Government Official History series began in 1919 with wartime histories, and the peace- time series was inaugurated in 1966 by Harold Wilson. The aim of the series is to produce major histories in their own right, compiled by historians eminent in the field, who are afforded free access to all relevant material in the official archives. The Histories also provide a trusted secondary source for other historians and researchers while the official records are still closed under the 30-year rule laid down in the Public Records Act (PRA). The main criteria for selection of topics are that the histories should record important episodes or themes of British history while the official records can still be supplemented by the recollections of key players; and that they should be of general interest, and, preferably, involve the records of more than one government department. The United Kingdom and the European Community: Vol. I: The Rise and Fall of a National Strategy,1945–1963 Alan S. Milward Secret Flotillas Vol. I: Clandestine Sea Operations to Brittany,1940–1944 Vol. II: Clandestine Sea Operations in the Mediterranean,North Africa and the Adriatic,1940–1944 Sir Brooks Richards SOE in France M. R. D. Foot The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: Vol. I: The Origins of the Falklands Conflict Vol. II: The 1982 Falklands War and Its Aftermath Lawrence Freedman Defence Organisation since the War D. C. Watt SOE in France An Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France 1940–1944 M.