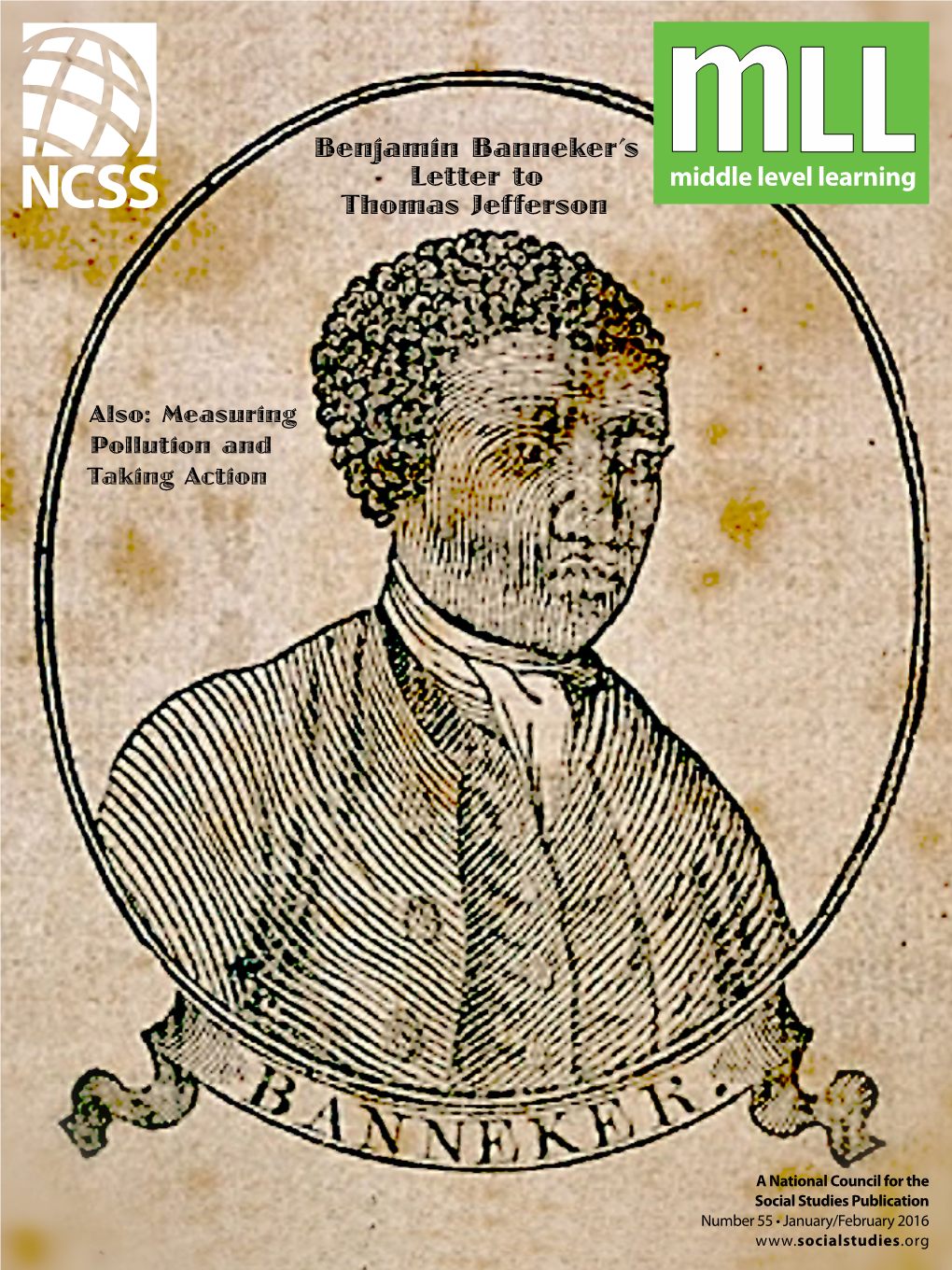

Benjamin Banneker's Letter to Thomas Jefferson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on the Almanacs of Massachusetts

1912.] Almmmcs of Massachusetts. 15 NOTES ON THE ALMANACS OF MASSACHUSETTS. BY CHARLES L. NICHOLS The origin of the almanac is wrapped in as much obscurity as that of the science of astronomy upon which its usefulness depends. It is possible, however, to trace some of the steps of its evolution and to note the uses to which it has been applied as that evolution has taken place. « When Fabius, the secretary of Appius Claudius, stole the fasti-sacri or Kalendares of the Roman priest- hood three hundred years before Christ, and exhibited the white tablets on the walls of the Forum, he not only struck a blow for reUgious freedom, but also gave to the people a long coveted source of information. Until that period no fast or holy-day had been pro- claimed except by the decision of the priests, since by their secret methods were made the calculations for those days. From that time the calendar of days has belonged to the people themselves, and has held an important position in the almanac of all nations. When Ptolemy in 150, A. D., prepared his catalogue of stars, and laid the foundation for more exact and con- tinuous records of their movements, the development of the Ephemeris, or daily note-book of the planets' places in our almanacs was assured. The meaning of the "man of signs," which is still so commonly seen, was minutely described by Manil- ius in his Astronomicon, written in the reign of the Emperor Tiberius. Origen and Jamblicus state that the principle underlying this belonged to a much earlier 16 American Aritiquarian Society. -

AN ASTRONOMICAL ALMANAC for the YEAR 348/9 P S (P

Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab Bind 36, no. 4 Hisi. Filol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 36, no. 4 (1956) AN ASTRONOMICAL ALMANAC FOR THE YEAR 348/9 P s (P. Heid. Inv. No. 34) BY O. NEUGEBAUER København 1956 i kommission hos Ejnar Munksgaard D et K o n g e l ig e D a n sk e V idenskabernes Selsk a b udgiver følgende publikalionsrækker: L'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Lettres de Danemark publie les séries suivantes: BibliograTisk forkortelse Abréviation bibliographique Oversigt over selskabets virksomhed (8°) Overs. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Annuaire) Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser (8°) Hist. Filol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Historisk-filologiske Skrifter (4°) Hist.'Filol. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Histoire et Philologie) Arkæologisk-kunsthistoriske Meddelelser (8°) Arkæol. Kunsthist. Medd. Dan. 0 Vid. Selsk. Arkæologisk-kunsthistoriske Skrifter (4°) Arkæol. Kunsthist. Skr. Dan. Vid. (Archéologie et Histoire de l’Art) Selsk. Filosofiske Meddelelser (8°) Filos. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Philosophie) Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser (8°) Mat. Fys. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Mathématiques et Physique) Biologiske Meddelelser (8°) Biol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. Biologiske Skrifter (4°) Biol. Skr. Dan. Vid. Selsk. (Biologie) Selskabets sekretariat og postadresse: Dantes plads 5, København V. L ’adresse postale du secrétariat de l’Académie est: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Dantes plads 5, København V, Danmark. Selskabets kommissionær: Ejnar Munksgaard’s forlag, Nørregade 6, København K. Les publications sont en vente chez le commissionnaire: E jnar Munksgaard, éditeur. Nørregade 6, København K, Danmark. Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab Bind 36, no. 4 Hist. -

Iowner of Property

A.NO. 10-300 ^.-vo-'" THEME 7: AMERIC' AT WORK, 7f-Engineering UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT Or ( HE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS _____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Benjamin Banneker: SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone (milestone) of the District of Columbia______ AND/OR COMMON Intermediate Stone of the District of Columbia LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 18th and Van Buren Streets _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Arlington VICINITY OF 10 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 Arlington 013 UCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT .X.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^_ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL 2LPARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS X-OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Arlington County Board_______ STREET & NUMBER Court House, 1400 N Court House Road CITY. TOWN STATE Arlington VICINITY OF Virginia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. NaHonal Archives of the United States STREET & NUMBER Seventh and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None Known DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE _GOOD —RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The SW-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone of the District of Columbia falls on land owned by Arlington County Board in the suburbs known as Falls Church Park at 18th Street and Van Buren Drive, Arlington, Virginia. -

Almond Almanac

ALMOND BOARD OF CALIFORNIA 20 A 20 L M ALMOND ALMANAC 2020 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 20 ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCING THE CALIFORNIA ALMOND COMMUNITY 2 Mission + Vision Welcome to the 2020 3 2020 Milestones Almond Almanac 4 About Our Community Within these pages you will find a ALMOND BOARD OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAMS comprehensive overview of California almonds—the state’s #1 crop by 6 Programs + Budget acreage, #1 ag export and #2 crop 7 Almond Orchard 2025 Goals by value, and the #1 specialty crop 8 California Almond Sustainability Program export in the U.S. 9 Research Overview 10 Production and Environmental Research For almond farmers and processors, 14 Nutrition Research this is your annual accounting 16 Almond Quality + Food Safety of how your investment in the 17 Global Technical + Regulatory Affairs Almond Board of California (ABC) is 18 Global Communications leveraged to build long-term demand 21 Global Market Development for California almonds around 22 Regional Market Updates the world, as well as protect that demand from erosion due to growing CALIFORNIA ALMOND FACTS AND FIGURES challenges, and an overview of ABC- funded research that underpins the 30 California Almond Forecasts vs. Actual Production continuous improvement efforts of 31 California Almond Crop Estimates vs. Actual Receipts the California almond community. 32 California Almond Acreage + Farm Value 33 Crop Value + Yield per Bearing Acre For anyone interested in California 35 California Almond Production by County almonds, the Almanac provides the 36 California Almond Receipts by County + Variety latest statistics1 about California 37 Top Ten Almond-Producing Varieties almond production, acreage 38 Position Report of California Almonds and varieties, as well as global 39 World Destinations shipment and market information. -

Benjamin Banneker: Boundary Stone (Milestone) of the C0NT:Nljai;Gbsiieet District of Colvmbia ITEM NUMBER 8 PAGE Five (Reference Notes)

&>rm H- to-~CO ~37%' THEME AMERlCA 7f-Engineering {R**. 7: AT WORK, L;NITEDST.ATES DEPAKT?.~~NTOF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NAZOMAk XZ>GIS'3";8OF lEEi5TOIRIC PLACES 9PiV3HTOXY -- NOWNAXON FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPtElE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL EFITRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS "7,. - HISTORIC Benjmin knneker: SIV-9 lntamediate Eoundary Stom (milestme) of the District of Columbia AND/OR COMMOH Inbrmediate Sbns of the District of Columbia a~oclno~ STREET & NUMBER , .. 18th and Van Buren Streefs -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Arlington ,VICINITI OF 10 STATE CODE COUNTY Virginia 51 Arlington , $fE 3CLASSIPICATION CATEGORY OHTNEASHlP STAtU S . PWESEHTUSE -DISTRICT XPUELIC -OCCUPIED AGRICULTURE -MUSEUM .-BUILDIHGISI -PRIVATE X,UNOCCUPIED -COMMERCIAL XPARK -STRUCTURE -BOTH -WORK IN PROGRESS -EDUCATIONAL -PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITIO?4 ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT -RELIGIOUS XOUECT -IN PROCESS -YES RESTRICTED -GOVERNMENT -SCIENTIFIC -BEING CONSIDERED YES. UNRESTRICTED -INDUSTRIAL -TRANSPORTATION -NO -MILITARY ,OTHER: 3;lo'~h~~OF PROPERTY NAME Arjington County bard --.-- STREET & NUMBER Court Houso, 1400 N Court Hwse Rdad CITY. TOWN ST ATE Arlinuton ,VICINITY OF Virginia &LOCATION OF UGriL DXSCR1P'FION COURTHOUSE. OF OEEDSETC. Nationel Archives of the United States STREET & NUMBER Seventh and Pannsylvcmia Avenue, N .W . CITY. rowh STATE TlTiE Known . .- . DATE -FEDERAL STATE -COUNTI LOCAL D'POSlTO2k' FO2 SURVEY RiC0703 CITY. TOWN STATE DESCXIPT~ON \ CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECX ONE -UNALTERED KORIGINALSITE XALTEREO _MOVED DATE DESCRiaETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The 94-9 Intermediate Boundary Stone of the District of Columbia falls on land owned by Arlington County Board in the suburbs known as Falls Church Park at 18th Street and Van kren Drive, Arlington, Virginia. -

The Citizen's Almanac

M-76 (rev. 09/14) n 1876, to commemorate 100 years of independence from Great Britain, Archibald M. Willard presented his painting, Spirit of ‘76, Iat the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, PA. The painting depicts three generations of Americans fighting for their new nation’s freedom, one of whom is marching along though slightly wounded in battle. Willard’s powerful portrayal of the strength and determination of the American people in the face of overwhelming odds inspired millions. The painting quickly became one of the most popular patriotic images in American history. This depiction of courage and character still resonates today as the Spirit of ‘76 lives on in our newest Americans. “Spirit of ‘76” (1876) by Archibald M. Willard. Courtesy of the National Archives, NARA File # 148-GW-1209 The Citizen’s Almanac FUNDAMENTAL DOCUMENTS, SYMBOLS, AND ANTHEMS OF THE UNITED STATES U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Use of ISBN This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of the ISBN 978-0-16-078003-5 is for U.S. Government Printing Office Official Editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. The information presented in The Citizen’s Almanac is considered public information and may be distributed or copied without alteration unless otherwise specified. The citation should be: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Office of Citizenship, The Citizen’s Almanac, Washington, DC, 2014. -

Recipes Recipes the OLDF the OLDF Amazing Weatherphotosforeverymonth

anac er’s Alm Farm The Original E OF HUMOR” T DEGRE LEASAN “USEFUL, WITH A P The Old No. CCXXIV Farmer’s FOUNDED IN 1792 FOUNDED Almanac FARMER’S ALMANAC, FARMER’S ® 2016 Cooking AlmAnAcs FRESHwith The Old farmer’s almanac Quick CalendArs &Easy THE ORIGINAL ROBERT B. THOMAS B. ROBERT ORIGINAL THE ALSO FEATURING ASTRONOMICAL TABLES, TIDES, HOLIDAYS, ECLIPSES, ETC. ECLIPSES, HOLIDAYS, TIDES, TABLES, ASTRONOMICAL ALSO FEATURING f f WEATHER FORECASTS Meals For 18 Regions of the United States mAgAzines More Than 160 SUN, MOON, STARS, AND PLANETS Books Recipes! Healthy Salads and Hearty Soups p. 12 Hearty Vegetable 22 To-Die-For Pasta Desserts p. 88 ADVENTURERS • INVENTORS • DISCOVERERS p. 106 Breakfasts & Brunches, Breads, and More! The Old Farmer’s Almanac p. 2, p. 94 The 2016 Old Farmer’s Almanac Calendar Recipes • The Old Farmer’s Almanac • Easy and Delicious • A Guarantee of Goodness Every Day Country 2 016 Calendar THE OLD FARMER’S ALMANAC LENDAR 2016 CA 2016 CALENDAR Wide open spaces and comforting places. Advice, Folklore, and Gardening Secrets from The Old Farmer’s Almanac Amazing weather photos for every month. RELEASE dAtE: SEptEmbER 8, 2015 the 2016 old farmer’s almanac THE 2016 OLD FARMER’S Almanac UPC 0 14021 01412 0 • $6.99 272 pages • 5 5⁄16" × 8" • Softcover The oldest continuously published periodical (now in its 224th year!) holds its place as the best-selling annual in North America, bringing readers wit, wisdom, tips, advice, fun facts, recipes, and its famous (always 80% accurate!) long-range weather forecasts. Hardcover: -

Notes on the Calendar and the Almanac

1914.] Notes on Calendar and Almanac. 11 NOTES ON THE CALENDAR AND THE ALMANAC. BY GEORGE EMERY LITTLEFIELD. In answering the question, why do the officers of pub- he libraries and bibliophiles so highly esteem and strive to make collections of old calendars and almanacs, it may be said that the calendar was coeval with and had a great influence upon civilization. Indeed, the slow but gradual formation of what we know as a calendar is an excellent illustration of the progress of civilization. At first it was a very crude scheme for recording the passing of time, deduced from irregular observations of the rising and setting of a few fixed stars, by a people who had but recently emerged from barbarism. The resultant table was of very little value and required constant revision and correction. It was only by long and patient study and observation, by gaining knowledge from repeated failures, that finally was produced the accurate and scientific register, which today bears the name of calendar. Furthermore, the material and shape of the tablet upon which the calendar was engraved or printed, was a constant .temptation to artists to decorate it with pen- cil or brush, which caused it to become a valuable me- dium for inculcating in the minds of the people, ideas of the sublime and beautiful, and never more so than at the present time. As regards the almanac, it also is of ancient memory, as we have positive evidence of its existence more than twelve hundred years before the Christian era. To its compilation scientists, philosophers, theologians, poets 12 American Antiquarian Sodety. -

Benjamin Banneker's Original Handwritten Document: Observations and Study of the Cicada

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 4 | Issue 1 January 2014 Benjamin Banneker's Original Handwritten Document: Observations and Study of the Cicada Janet E. Barber Asamoah Nkwanta Morgan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the African American Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Nonfiction Commons, Other Mathematics Commons, Other Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Barber, J. E. and Nkwanta, A. "Benjamin Banneker's Original Handwritten Document: Observations and Study of the Cicada," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 4 Issue 1 (January 2014), pages 112-122. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.201401.07 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol4/ iss1/7 ©2014 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. -

Astronomy and Astrology in Al-Andalus and the Maghrib by Julio Samsó Variorum Collected Studies Series CS887. Aldershot, UK/Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007

Astronomy and Astrology in al-Andalus and the Maghrib by Julio Samsó Variorum Collected Studies Series CS887. Aldershot, UK/Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007. Pp. xiv+366. ISBN 0--7546--5934--1.Cloth $124.95 Reviewed by J. L. Mancha University of Seville [email protected] Over the last 30 years, Julio Samsó and his colleagues from the Uni- versity of Barcelona, most of them his former students, have contin- ued the work of Millás Vallicrosa in the first half of the 20th century and have substantially modified our knowledge of the history of as- tronomy and its related sciences in the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. We are much indebted to them for their efforts in making new textual evidence available, since this is the first task of historians. This interesting collection of articles is the second, and very welcome, volume of Samsó’s papers in the Variorum series. The first, Islamic Astronomy and Medieval Spain—20 papers published between 1977 and 1994 (four of them co-authored with M. Comes, F. Castelló, H. Mielgo, and E. Millás)—covered a wide range of topics: the survival of Latin astronomy and astrology in al-Andalus, Eastern influences in Andalusian astronomy and trigonometry, astronomical theory (mainly the work of Ibn al-Zarq¯alluhand his school on access and recess1 and solar theory) and the presence of Islamic materials in the works sponsored by Alfonso X. In this collection, two papers on ‘eccentric’ subjects are, in my opinion, especially worth mention- ing: the one devoted to a homocentric solar model described by Ab¯u Jacfar al-Kh¯azin(d. -

Pages Including Illustrations Are in Italics Abano, Pietro D', 14, 47, 75N

INDEX Pages including illustrations are in italics Abano, Pietro d’, 14, 47, 75n, 106, 110, 110n, Alexander, J.J.G., 392n 117, 131, 133, 133n, 137, 267, 270, 270n, 340, Alexandria, 15, 17, 342 342, 361, 363, 368 Alfonso X of Castile, 26, 67n, 69–70, 72, Abeele, Baudouin van de, 30n 127, 134, 198 Abenezrah, Kinki, 168 al-Kindi, 29, 128 Abohali, 3 Allen, Don Cameron, 189n Abraham bar Ḥiyya (Savasorda), 100, 106–7 Allen, Michael J.B, 268n Abraham ibn Ezra (Abenezra), 15, 70n, 100, al-Mamun, 103 106, 110, 110n, 118n, 125, 125n, 126 almanac, 24, 97, 138, 141, 149–50, 155, 157, Abry, Josèphe-Henriette, 36n, 53n 161, 163–75, 177, 188–190, 195n, 216, 220–1, Abū Maʿšar, 21, 21n, 29, 29n, 46, 104, 104n, 230, 256, 312–3, 314n, 320, 322, 328–31, 338–9, 339n, 340–2, 344 387, 411, 414, 423, 425 Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the al-Mansur, 103 Lynxes), 324 Alphonsine Tables, 26, 67, 67n, 72, 131, acceleration, 240 249 Accorinti, Domenico, 36n al-Khwarizmi, 66–68 Ackermann, Silke, 356n, 359n, 360n al-Souphi, 127 Acosta, José de, 400n, 402, 402n, 409n Altobelli, Ilario, 65n Adelard of Bath, 21, 21n Alverny, Marie-Therèse d’, 345n Adorno, Theodor, 431, 432n al-Zarqali, 66–68 aether, 275 Amabile, Luigi, 185n, 186n, 316n, 327n Agostino di Duccio, 375 Ammann, Peter J., 261n Agrippa von Nettesheim, Cornelius, 53–4, Angeli, Alessandro degli, 412n 97 angle, 44, 59, 63–4, 121, 240, 242, 409n Ahmad ibn Yusuf ibn al-Dayah, 92 Anima mundi, 244–5 Aiton, E.J., 244n Annus mirabilis, 1484 as, 30; 1524 as, 183 Akasoy, Anna, 6n Antichrist, 97, 101, 113–5, 120, 123, -

OAAA E-Weekly Newsletters

OAAA E-Weekly Newsletter Office of African American Affairs October 7, 2019 Special Announcement OAAA/GradSTAR Lunch Series: Tuesdays @ DuBois (NEXT LUNCH: Tuesday, October 15) Every Second & Fourth Tuesday 12:30 pm-2:00 pm W.E.B. DuBois Conference Room - #2 Dawson’s Row Join Dean Patrice Grimes for lunch and conversation. Space is limited. RSVP to reserve your spot: https://doodle.com/poll/7a6ew5e4wftk4tic OAAA/GradSTAR 2019 Personal Branding Series Wednesdays, October 16, 23, 30, Nov. 6 & Recognition Dinner Nov.13 – 6:00 pm-7:30 pm Application deadline extended: WEDNESDAY, October 9,2019 at 5:00 pm Are you interested in learning how to market yourself, your skills, and your experiences to secure a full time job, internship or research opportunity? The 5th Annual OAAA/GradSTAR Personal Branding Seminar may be for you! This seminar workshop includes resume writing, delivering personal pitches, and networking tips hosted by OAAA and Altria Group Inc. Students from all years are encouraged to apply online. Apply Here! Questions? Feel free to reach out to Dean Grimes. Hope to see you there! The Office of African-American Affairs is on FACEBOOK! LIKE US to keep up-to-date with events and more info about OAAA! Mark Your Calendar Saturday, October 5 – Tuesday October 8 – Fall Break/Reading Days (no classes) Friday, October 18 - Sunday, October 20 – Family Weekend & Fall Convocation Tuesday, October 23 – Last day to DROP a course with a “W” Thursday, October 31 – Deadline to pay the annual premium for the Aetna Student Health Insurance plan Wednesday,