Private Native Forestry Field Guide for the River Red Gum Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016 Under The

New South Wales Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016 under the Water Management Act 2000 I, Niall Blair, the Minister for Lands and Water, in pursuance of sections 45 (1) (a) and 45A of the Water Management Act 2000, being satisfied it is in the public interest to do so, make the following Order to amend the Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2012. Dated this 29th day of June 2016. NIALL BLAIR, MLC Minister for Lands and Water Explanatory note This Order is made under sections 45 (1) (a) and 45A of the Water Management Act 2000. The object of this Order is to amend the Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2012. The concurrence of the Minister for the Environment was obtained prior to the making of this Order as required under section 45 of the Water Management Act 2000. 1 Published LW 1 July 2016 (2016 No 371) Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016 Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016 under the Water Management Act 2000 1 Name of Order This Order is the Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016. 2 Commencement This Order commences on the day on which it is published on the NSW legislation website. 2 Published LW 1 July 2016 (2016 No 371) Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources Amendment Order 2016 Schedule 1 Amendment of Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Unregulated and Alluvial Water Sources 2012 [1] Clause 4 Application of this Plan Omit clause 4 (1) (a) (xxxviii) and (xxxix). -

No. XIII. an Act to Provide More Effectually for the Representation of the People in the Legis Lative Assembly

No. XIII. An Act to provide more effectually for the Representation of the people in the Legis lative Assembly. [12th July, 1880.] HEREAS it is expedient to make better provision for the W Representation of the People in the Legislative Assembly and to amend and consolidate the Law regulating Elections to the Legisla tive Assembly Be it therefore enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of New South Wales in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows :— Preliminary. 1. In this Act the following words in inverted commas shall have the meanings set against them respectively unless inconsistent with or repugnant to the context— " Governor"—The Governor with the advice of the Executive Council. "Assembly"—The Legislative Assembly of New South Wales. " Speaker"—The Speaker of the Assembly for the time being. " Member"—Member of the Assembly. "Election"—The Election of any Member or Members of the Assembly. " Roll"—The Roll of Electors entitled to vote at the election of any Member of the Assembly as compiled revised and perfected under the provisions of this Act. "List"—-Any List of Electors so compiled but not revised or perfected as aforesaid. " Collector"—Any duly appointed Collector of Electoral Lists. "Natural-born subject"—Every person born in Her Majesty's dominions as well as the son of a father or mother so born. " Naturalized subject"—Every person made or hereafter to be made a denizen or who has been or shall hereafter be naturalized in this Colony in accordance with the Denization or Naturalization laws in force for the time being. -

SURVEY of VEGETATION and HABITAT in KEY RIPARIAN ZONES of TRIBUTARIES of the MURRUMBIDGEE RIVER in the ACT: Naas, Gudgenby, Paddys, Cotter and Molonglo Rivers

SURVEY OF VEGETATION AND HABITAT IN KEY RIPARIAN ZONES OF TRIBUTARIES OF THE MURRUMBIDGEE RIVER IN THE ACT: Naas, Gudgenby, Paddys, Cotter and Molonglo Rivers Lesley Peden, Stephen Skinner, Luke Johnston, Kevin Frawley, Felicity Grant and Lisa Evans Technical Report 23 November 2011 Conservation Planning and Research | Policy Division | Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate TECHNICAL REPORT 23 Survey of Vegetation and Habitat in Key Riparian Zones of Tributaries of the Murrumbidgee River in the ACT: Naas, Gudgenby, Paddys, Cotter and Molonglo Rivers Lesley Peden, Stephen Skinner, Luke Johnston, Kevin Frawley, Felicity Grant and Lisa Evans Conservation, Planning and Research Policy Division Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate GPO Box 158, CANBERRA ACT 2601 i Front cover: The Murrumbidgee River and environs near Tharwa Sandwash recreation area, Tharwa, ACT. Photographs: Luke Johnston, Lesley Peden and Mark Jekabsons. ISBN: 978‐0‐9806848‐7‐2 © Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, Canberra, 2011 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to appropriate referencing of the source. This document should be cited as: Peden, L., Skinner, S., Johnston, L., Frawley, K., Grant, F., and Evans, L. 2011. Survey of Vegetation and Habitat in Key Riparian Zones in Tributaries of the Murrumbidgee River in the ACT: Cotter, Molonglo, Gudgenby, Naas and Paddys Rivers. Technical Report 23. Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, Canberra. Published by Conservation Planning and Research, Policy Division, Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate. http://www.environment.act.gov.au | Telephone: Canberra Connect 132 281 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was prepared with funding provided by the Australian Government National Action Plan for Salinity and Water Quality. -

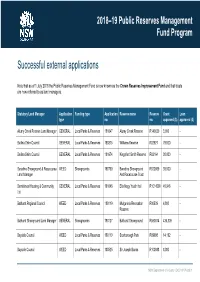

Successful External Applications

2018–19 Public Reserves Management Fund Program Successful external applications Note that as of 1 July 2018 the Public Reserves Management Fund is now known as the Crown Reserves Improvement Fund and that trusts are now referred to as land managers. Statutory Land Manager Application Funding type Application Reserve name Reserve Grant Loan type no. no. approved ($) approved ($) Alumy Creek Reserve Land Manager GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181647 Alumy Creek Reserve R140020 3,600 - Ballina Shire Council GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 180875 Williams Reserve R82927 79,000 - Ballina Shire Council GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181674 Kingsford Smith Reserve R82164 30,000 - Baradine Showground & Racecourse WEED Showgrounds 180790 Baradine Showground R520059 38,500 - Land Manager And Racecourse Trust Barriekneal Housing & Community GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181646 Ella Nagy Youth Hall R1014508 40,946 - Ltd Bathurst Regional Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180119 Mulgunnia Recreation R80539 4,800 - Reserve Bathurst Showground Land Manager GENERAL Showgrounds 180127 Bathurst Showground R590074 435,309 - Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180110 Scarborough Park R69998 14,192 - Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180525 Sir Joseph Banks R100088 8,000 - NSW Department of Industry | DOC18/176333| 1 2018–19 Public Reserves Management Fund Program Statutory Land Manager Application Funding type Application Reserve name Reserve Grant Loan type no. no. approved ($) approved ($) Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves -

3F38373009842c86616a

•CANBERRA ' BUSH WALKING •CLUB INC NEWSLETTER GPO Box 160, Canberra ACT 2601 VOLUMB 34 SEPTEI'ffiER 1998 NUMBER 9 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Greg BUckley Award & other Prizes 8pm Wednesday 16 September Dickson Library Community Room (entrance at rear of library) Make the most of the evening and Join other members at 6.00pm for a convivial (B'YO) meal at the Pho P1w Quoc Restaurant in Cape Street, Dickson. Try to be early to ensure there will be ample time to finish and still get to the meetIng In comfortable time Walks to Allan Mikkelsen Ph: 6278 3164 E-mail: [email protected] SD Century Courts, 4 Beetaloo St, Hawker ACT 2614 Articles etc. for publication to Paul Edstein Ph: 6271 4514(w) 6288 1398 (h) Fax: 6271 4560 (w) E-mail: [email protected] 19 Gamor St, Waramanga ACT 2611 PRESIDENT'S PRATTLE And so to my final "Prattle". It doesn't seem those people, but also to everyone who has supported like I've been compiling "Prattles" for two years, so I walks, other activities and Club meetings. think I must have enjoyed it! As the saying goes "time flies when you're having fun". I have to admit though I would just like to mention here that activity leaders there were months when I really had to search for do have one important obligation when they something I thought was worth printing - okay, not return home from the activity. That is to phone the everyone thought it was worth printing! Some Check-in Officer (as early as possible or at least members didn't agree with what I had to say on within 24 hours) and advise the safe completion of the occasions and I will always think that was good for trip and the number of people who went - and the Club. -

Gazetteer of West Virginia

Bulletin No. 233 Series F, Geography, 41 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOU A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA I-IEISTRY G-AN3STETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 A» cl O a 3. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OP THE INTEKIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. C. , March 9, 190Jh SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of West Virginia! Very respectfully, HENRY GANNETT, Geogwvpher. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 3 A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA. HENRY GANNETT. DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. The State of West Virginia was cut off from Virginia during the civil war and was admitted to the Union on June 19, 1863. As orig inally constituted it consisted of 48 counties; subsequently, in 1866, it was enlarged by the addition -of two counties, Berkeley and Jeffer son, which were also detached from Virginia. The boundaries of the State are in the highest degree irregular. Starting at Potomac River at Harpers Ferry,' the line follows the south bank of the Potomac to the Fairfax Stone, which was set to mark the headwaters of the North Branch of Potomac River; from this stone the line runs due north to Mason and Dixon's line, i. e., the southern boundary of Pennsylvania; thence it follows this line west to the southwest corner of that State, in approximate latitude 39° 43i' and longitude 80° 31', and from that corner north along the western boundary of Pennsylvania until the line intersects Ohio River; from this point the boundary runs southwest down the Ohio, on the northwestern bank, to the mouth of Big Sandy River. -

Functioning and Changes in the Streamflow Generation of Catchments

Ecohydrology in space and time: functioning and changes in the streamflow generation of catchments Ralph Trancoso Bachelor Forest Engineering Masters Tropical Forests Sciences Masters Applied Geosciences A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Trancoso, R. (2016) PhD Thesis, The University of Queensland Abstract Surface freshwater yield is a service provided by catchments, which cycle water intake by partitioning precipitation into evapotranspiration and streamflow. Streamflow generation is experiencing changes globally due to climate- and human-induced changes currently taking place in catchments. However, the direct attribution of streamflow changes to specific catchment modification processes is challenging because catchment functioning results from multiple interactions among distinct drivers (i.e., climate, soils, topography and vegetation). These drivers have coevolved until ecohydrological equilibrium is achieved between the water and energy fluxes. Therefore, the coevolution of catchment drivers and their spatial heterogeneity makes their functioning and response to changes unique and poses a challenge to expanding our ecohydrological knowledge. Addressing these problems is crucial to enabling sustainable water resource management and water supply for society and ecosystems. This thesis explores an extensive dataset of catchments situated along a climatic gradient in eastern Australia to understand the spatial and temporal variation -

Annual Operations Plan Murrumbidgee Valley 2019-20 Acronym Definition

Annual Operations Plan Murrumbidgee Valley 2019-20 Acronym Definition Available Water Contents AWD Determination Introduction 2 BLR Basic Landholder Rights The Murrumbidgee River System 2 Regulated and unregulated system flow trends 3 BoM Bureau of Meteorology Rainfall trends 3 CWAP Critical Water Advisory Panel Inflows to dam 4 Critical Water Technical Water users in the valley 4 CWTAG Advisory Group Water availability 7 Department of Primary Current drought conditions 9 DPI CDI Industries - Combined Blowering Dam storage 10 Drought Indicator Burrinjuck Dam storage 10 Department of Planning, Inter valley transfer 11 Industry and Environment - DPIE EES Operational surplus 12 Environment, Energy & Science Transmission losses 12 Resource assessment 15 DPI Department of Primary End of System flow targets 17 Fisheries Industries - Fisheries Department of Planning, Water resource forecast 18 DPIE Industry and Environment - Water Murrumbidgee catchment - past 24 month rainfall 18 Water Blowering Dam - past 24 month inflows/statistical inflows 19 FSL Full Supply Level Burrinjuck Dam - past 24 month inflows/statistical inflows 19 Weather forecast - 3 month BoM forecast 20 HS High Security Murrumbidgee storage forecast 20 IRG Incident Response Guide Annual operations 22 Infrastructure State ISEPP Environmental Planning Operational rules 22 Policy Deliverability 24 Overall scenario assumptions 24 LGA Local Government Areas River Operations Stakeholder ROSCCo Critical dates 25 Consultation Committee S&D Stock & Domestic Potential projects 26 Valley Technical Advisory vTAG Group Introduction The annual operations plan provides an outlook for the coming year in the Murrumbidgee Valley and considers the current volume of water in storages and weather forecasts. This plan may be updated as a result of significant changes to the water supply situation. -

List of North Carolina Bridges

3/31/21 Division County Number DOT # Route Across Year Built Posted SV Posted TTST 7 Alamance 2 000002 SR1529 PRONG OF HAW RIVER 1998 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 3 000003 SR1529 DRY CREEK 1954 20 29 7 Alamance 6 000006 SR1504 TRAVIS CREEK 2004 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 7 000007 SR1504 TICKLE CREEK 2009 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 11 000011 NC54 HAW RIVER 2001 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 12 000012 NC62 BIG ALAMANCE CREEK 1999 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 13 000013 SR1530 HAW RIVER 2002 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 14 000014 NC87 CANE CREEK 1929 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 15 000015 SR1530 HAW RIVER 1957 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 16 000016 NC119 I40, I85 1994 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 18 000018 SR1561 HAW RIVER 2004 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 22 000022 SR1001 MINE CREEK 1951 23 30 7 Alamance 23 000023 SR1001 STONEY CREEK 1991 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 24 000024 SR1581 STONY CREEK 1960 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 26 000026 NC62 GUNN CREEK 1949 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 27 000027 SR1002 BUTTERMILK CREEK 2004 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 28 000028 SR1587 BUTTERMILK CREEK 1986 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 31 000031 SR1584 BUTTERMILK CREEK 2005 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 32 000032 SR1582 BUTTERMILK CREEK 2012 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 33 000033 NC49 STINKING QUARTER CREEK 1980 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 34 000034 NC54 BACK CREEK 1973 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 35 000035 NC62 HAW RIVER 1958 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 36 000036 SR1613 TOM'S CREEK 1960 35 41 7 Alamance 37 000037 SR1611 PRONG STONEY CREEK 2013 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 38 000038 SR1611 STONEY CREEK 1960 33 39 7 Alamance 39 000039 SR1584 PRONG BUTTERMILK CREEK 1995 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 40 000040 NC87 BRANCH OF VARNALS CREEK 1929 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 41 000041 SR1002 STONEY CREEK 1960 34 37 7 Alamance 42 000042 SR1002 TOM'S CREEK 1960 34 38 7 Alamance 43 000043 SR1763 JORDAN CREEK 1995 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 44 000044 SR1768 JORDAN'S CREEK 1968 5 0 7 Alamance 45 000045 SR1002 JORDAN CREEK 2008 LGW LGW 7 Alamance 47 000047 SR1226 I40, I85 2004 LGW LGW This report includes NC Bridges that are less than 20' in length. -

ACT Aquatic and Riparian Conservation Strategy

5 © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2018 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from: Director-General, Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government, GPO Box 158, Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6207 1923 Visit the EPSDD Website ISBN 978-1-921117-71-8 Accessibility The ACT Government is committed to making its information, services, events and venues as accessible as possible. If you have difficulty reading a standard printed document and would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, such as large print, please phone Access Canberra on 13 22 81 or email the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate at [email protected]. If English is not your first language and you require a translating and interpreting service, phone 13 14 50. If you are deaf, or have a speech or hearing impairment, and need the teletypewriter service, please phone 13 36 77 and ask for Access Canberra on 13 22 81. For speak and listen users, please phone 1300 555 727 and ask for Access Canberra on 13 22 81. For more information on these services visit Relay Service website. CONTENTS PART A CONSERVATION STRATEGY COMMON TERMS IN THE TEXT REQUIRING CLARIFICATION vi VISION vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 OVERVIEW 2 1.2 OBJECTIVES 2 1.3 ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT APPROACH 2 1.4 DEFINITION OF AQUATIC AND RIPARIAN AREAS 3 1.5 SCOPE OF THE STRATEGY 3 1.6 STRUCTURE OF THE STRATEGY 7 1.7 LINKS BETWEEN -

Environmental Water Delivery: Murrumbidgee Valley

ENVIRONMENTAL WATER DELIVERY Murrumbidgee Valley JANUARY 2012 V1.0 Image Credits Telephone Bank Wetlands © DSEWPaC, Photographer: Simon Banks River red gums, Yanga National Park © DSEWPaC, Photographer: Dragi Markovic Sinclair Knight Merz (2011). Environmental Water Delivery: Murrumbidgee Valley. Prepared for Commonwealth Environmental Water, Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra. ISBN: 978-1-921733-28-4 Commonwealth Environmental Water acknowledges the following organisations and individuals who have been consulted in the preparation of this document: Murray-Darling Basin Authority Ben Gawne (Murray-Darling Freshwater Research Centre) Garry Smith (DG Consulting) Daren Barma (Barma Water Resources) Jim Parrett (Rural and Environmental Services) Karen McCann (Murrumbidgee Irrigation) Rob Kelly Chris Smith James Maguire (NSW Office of Environment and Heritage) Andrew Petroeschevsky (NSW Dept. Primary Industries) Lorraine Hardwick (NSW Office of Water) Adam McLean (State Water Corporation) Eddy Taylor (State Water Corporation) Arun Tiwari (Coleambally Irrigation Cooperative Limited) Austen Evans (Coleambally Irrigation Cooperative Limited) Published by Commonwealth Environmental Water for the Australian Government. © Commonwealth of Australia 2011. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should -

Adjungbilly Creek Catchment - Save Our Species Project

Photo: D Hunter Adjungbilly Creek Catchment - Save Our Species Project The Adjungbilly Creek is a unique catchment in the Riverina Local Land Services region due to it’s populations of a number of endangered plants and animals. The catchment is home to Macquarie Perch, the Booroolong Frog, White Box, Yellow Box, Blakelys Red Gum, Grassy Woodlands, Coolac-Tumut Serpentinite and Shrubby Woodland. Over the past five years, Riverina Local Land Services (LLS) has worked with Landcare, landholders and researchers to gain an understanding of the extent of the population of these endangered species as well as undertaking targeted works to assist their recovery. Through this ongoing project, we have improved habitat for endangered species and ecological communities through the protection and restoration of 233 hectares of the catchment by revegetating gullies to improve water quality, protected areas of native vegetation by installing 46 kilometres of fencing and re-established corridors of native vegetation by planting 30,000 native trees and shrubs. With additional funding from the NSW Government, a range of incentives is on offer to landholders to continue important works, which will support the recovery of these iconic species and communities. What assistance is available? • Protecting areas of riparian and terrestrial native Incentive Funding is being offered to Adjungbilly vegetation: through the provision of standard landholders to undertake targeted on-ground fencing materials, understorey plantings and restoration and conservation works to aid species alternative stock water recovery whilst improving their farm viability. • Re-establishing corridors of riparian and terrestrial native vegetation: through the The works have also supported landholders to improve provision of standard fencing materials, site their land management.