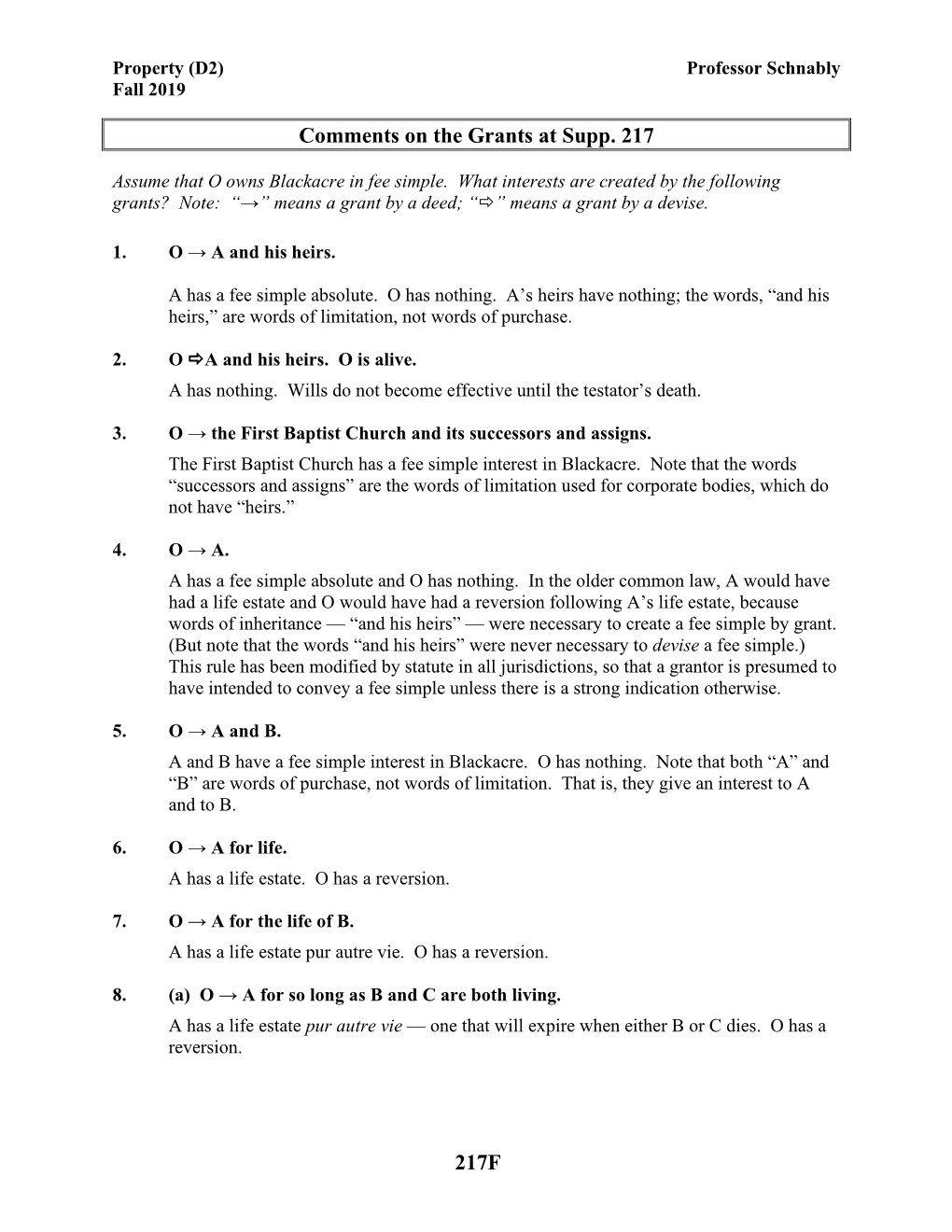

Comments on Grants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Reasons to Remember the Estate Taxation of Reversions

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Liberty University School of Law Summer 2009 New Reasons to Remember the Estate Taxation of Reversions F. Philip Manns Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lusol_fac_pubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Manns, F. Philip, "New Reasons to Remember the Estate Taxation of Reversions" (2009). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 4. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lusol_fac_pubs/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School of Law at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW REASONS TO REMEMBER THE ESTATE TAXATION OF REVERSIONS F. Philip Manns, Jr.∗ Editors’ Synopsis: When a transfer of real property creates a future interest in a party without expressly providing whether that party must survive all others in possession prior, the common law has traditionally refused to imply such a requirement. Recently, various reform movements have proposed reversing this rule. Where such a reversal fails to likewise negate the reversion created by the change, the transferor-possessor of the reversion faces complicated tax issues as a result. In this Article, the author provides an overview of the various attempts to reverse the rule and goes through the complicated actuarial mathematics that are required to assess the tax liability of the possessor of the reversion. I. INTRODUCTION................................................................... 324 II. THE NICS RULE AND ITS NEGATION BY UPC SECTION 2-707 ................................................................... 330 III. -

Usufruct Study Guide

Article 562 ± 578 1. Define usufruct. Usufruct is a real right by virtue of which a person is given the right to enjoy the property of another with the obligation of preserving its form and substance, unless the title constituting it or the law provides otherwise. 2. What are the three fundamental Rights Appertaining to Ownership? Ownership consists of three fundamental rights, to wit: - jus disponende (right to dispose) - jus utendi (right to use) - jus fruendi (right to the fruits) 3. Of the above-mentioned fundamental rights, what consists usufruct and naked ownership? The combination of the jus utendi and jus fruendi is called usufruct. The remaining right jus disponendi is really the essence of what is termed ³naked ownership´. 4. What right is transferred to the usufructuary and what right is remained with the owner? In a usufruct, only the jus utendi and jus fruendi over the property is transferred to the usufructuary. The owner of the property maintains the jus disponendi or the power to alienate, encumber, transform, and even destroy the same. (Hemedes vs. CA, 316 SCRA 347 1999). 5. What are the formulae with respect to full ownership, usufruct, and naked ownership? The following are the formulae: - Full Ownership equals Naked Ownership plus Usufruct - Naked Ownership equals Full Ownership minus Usufruct - Usufruct equals Full Ownership minus Naked Ownership 6. What are the characteristics or elements of usufruct? The following are the characteristics or elements of usufruct: ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS: those without which it can not be termed usufruct: (a) It is REAL RIGHT (whether registered in the Registry of Property or not). -

Future Interests

Future Interests Interests in the Transferor • Reversion • Possibility of Reverter (NOT a possibility of reversion) • Right of Entry/Power of Termination Interests in the Transferee • Executory Interest • Vested Remainder • Contingent Remainder U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2007 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. D E Present and Future Interests F E Present Interest Future Interest A S Fee Simple Determinable Possibility of Reverter I B (transferor) L Fee Simple Subject to Executory Interest E Executory Limitation (transferee) E Fee Simple Subject to Right of Entry/Power of S Condition Subsequent Termination (transferor) T A T E S U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2007 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. 1 Vested Remainders • If given to an ascertained person AND • Not subject to a condition precedent (other than the natural termination of the preceding estate) • Precedent: (pri-seed-[c]nt) preceding in time or order; contingent upon some event occurring • Note: Not subject to the rule against perpetuities U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. Burke Copyright©2007 Marcilynn A. Burke All rights reserved. Provided for student use only. Types of Vested Remainders 1. Indefeasibly vested remainders • Certain to become possessory in the future • Cannot be divested U N I V E R S I T Y of H O U S T O N Professor Marcilynn A. -

1. Blackacre and Greenacre May Constitute Bonnie and Wally's Homestead Property

Q6 - July 2017 - Selected Answer 1 6) 1. Blackacre and Greenacre may constitute Bonnie and Wally's homestead property. The issue is whether two tracts of noncontiguous tracts of land may qualify as a rural homestead. Under Texas Law, a family may have an urban or rural homestead. An urban homestead exists where up to 10 contiguous acres within the city limits, or platted subdivision are used as a primary residence, are provided police and volunteer or paid fire protection, and at least three of the following services: water, natural gas, electricity, sewer, storm sewer. A homestead that does not qualify as urban is considered rural. A family may hold up to 200 non contiguous acres as a rural homestead. Here, Bonnie and Wally built a home on Blackacre, and Bonnie later inherited Greenacre which was a tract of land nearby and in the same county. Together, the tracts equal 125 acres and would be within the alloted amount for a rural homestead. So long as Bonnie and Wally maintain their primary residence on a part of the non-contiguous acres, the entirety of both tracts may be held as homestead where the land is used for the support of the family. 2. No, Big Oil's oil and gas lease is not valid. The issue is whether Wally had the right to, and did, validly grant an oil and gas lease to the covering Blackacre without Bonnie joined. Bonnie and Wally are married and they purchased Blackacre and built there home on it. If Blackacre is a homestead, both parties would have to be on an instrument conveying the property. -

Rights of Reverter and the Statute Quia Emptores

YALE LAW JOURNAL Vol. XXXVI MARCH, 1927 No. 5 RIGHTS OF REVERTER AND THE STATUTE QUIA EMPTORES W. R. VANCE "It was little the disposition of English lawyers," wrote Pro- fessor Gray in commenting upon the meagerness of the con- sideration given in English Law to determinable fees, "to trouble themselves about questions which did not come up practically." 1 The same thing could even more truly be said of American law- yers. If determinable fees and rights of reverter dependent upon them were of no more frequent occurrence in the United States than in England, there would certainly be no sufficient rea- son for giving further time to their discussion.2 But such is not the case. American courts have been frequently called upon to determine the nature and validity of such estates,3 and the I GRAY, RuLn AGAINST PERM UITIES (3d ed. 1915) § 779. 2 This paper is supplementary to an article by the author entitled The Quest for Tenure in the United States (1924) 33 YALE LAW JOURNm, 248. Since the publication of the first edition of GRAY, RuIm AGINST Pn- Pnrurnms (1886) there has been much discussion of determinable fees. The most notable contribution is that of Professor R. R. B. Powell, whose able and scholarly article, Determinable Fees (1923) 23 CoL. L. REv. 207, pre- sents the most complete and accurate survey of the authorities yet published. Mr. J. M. Zane's Determinable Fees in American Jurisdictions (1904) 17 HARv. L. REV. 297, is also interesting and valuable. 3 The cases are collected with comments by Powell, op. -

Constitutional

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 2 Article 10 Issue 2 Winter 1971 1971 Constitutional Law - Estates - Reversion of the Res of a Charitable Trust Which Failed Because It Necessitated Racially Discriminatory State Action Is Not Violative of the XIVth Amendment Where the Reversion Is by Operation of State Law, and Due to the State Court's Refusal to Apply the Doctrine of Cy Pres. Lawrence J. Casazza Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence J. Casazza, Constitutional Law - Estates - Reversion of the Res of a Charitable Trust Which Failed Because It Necessitated Racially Discriminatory State Action Is Not Violative of the XIVth Amendment Where the Reversion Is by Operation of State Law, and Due to the State Court's Refusal to Apply the Doctrine of Cy Pres., 2 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 390 (1971). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol2/iss2/10 This Case Comment is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-ESTATES-Reversion of the Res of a Charitable Trust which failed because it neces- sitated racially discriminatory state action is not violative of the XIVth Amendment where the Reversion is by operation of state law, and due to the state court's re- fusal to apply the doctrine of Cy Pres. -

QUESTION 1 Purchaser Acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988

QUESTION 1 Purchaser acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988. Seller had purchased the property in 1978. Throughout Seller's ownership, Blackacre had been described by a metes and bounds legal description, which Seller believed to include an island within a stream. Seller conveyed title to Blackacre to Purchaser through a special warranty deed describing Blackacre with the same legal description through which Seller acquired it. At all times while Seller owned Blackacre, she thought she owned the island. In 1978, she built a foot bridge to the island to allow her to drive a tractor mower on it. During the summer, she regularly mowed the grass and maintained a picnic table on the island. Upon acquiring Blackacre, Purchaser continued to mow the grass and maintain the picnic table during the summer. In 1994, Neighbor, who owns the property adjacent to Blackacre, had a survey done of his property (the accuracy of which is not disputed) which shows that he owns the island. In 1998, Neighbor demanded that Purchaser remove the picnic table and stop trespassing on the island. QUESTION: Discuss any claims which Purchaser might assert to establish his right to the island or which he may have against Seller. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 1 I. Mr. Plaintiffs Claims versus Mr. Neighbor One who maintains continuous, exclusive, open, and adverse possession of real property for the requisite statutory period may obtain title thereto under the principle of adverse possession. Edie v. Coleman, 235 Mo. App. 1289, 141 S.W. 2d 238 (1940), Vade v. Sickler, 118 Colo. 236, 195 P.2d 390 (1948). -

614.24 Reversion Or Use Restrictions on Land — Preservation. 1. No

1 LIMITATIONS OF ACTIONS, §614.24 614.24 Reversion or use restrictions on land — preservation. 1. No action based upon any claim arising or existing by reason of the provisions of any deed or conveyance or contract or will reserving or providing for any reversion, reverted interests or use restrictions in and to the land therein described shall be maintained either at law or in equity in any court to recover real estate in this state or to recover or establish any interest therein or claim thereto, legal or equitable, against the holder of the record title to such real estate in possession after twenty-one years from the recording of such deed of conveyance or contract or after twenty-one years from the admission of said will to probate unless the claimant shall, personally, or by the claimant’s attorney or agent, or if the claimant is a minor or under legal disability, by the claimant’s guardian, trustee, or either parent or next friend, file a verified claim with the recorder of the county wherein said real estate is located within said twenty-one year period. In the event said deed was recorded or will was admitted to probate more than twenty years prior to July 4, 1965, then said claim may be filed on or before one year after July 4, 1965. Such claims shall set forth the nature thereof, also the time and manner in which such interest was acquired. For the purposes of this section, the claimant shall be any person or persons claiming any interest in and to said land or in and to such reversion, reverter interest or use restriction, whether the same is a present interest or an interest which would come into existence if the happening or contingency provided in said deed or will were to happen at once. -

Superficie Rights and Usufruct in Cuba: Are They Real, Title Insurable Rights Jose Manuel Palli

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Law and Business Review of the Americas Volume 22 | Number 1 Article 9 2016 Superficie Rights and Usufruct in Cuba: Are They Real, Title Insurable Rights Jose Manuel Palli Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra Recommended Citation Jose Manuel Palli, Superficie Rights and Usufruct in Cuba: Are They Real, Title Insurable Rights, 22 Law & Bus. Rev. Am. 23 (2016) https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra/vol22/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law and Business Review of the Americas by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "SUPERFICIE" RIGHTS AND USUFRUCT IN CUBA: ARE THEY "REAL," "TITLE INSURABLE" RIGHTS? Josd Manuel Palli Esq.* FOREWORD HIS paper was originally written in May 2013, and was presented at the 9th Conference on Cuban and Cuban-American studies staged by the Cuban Research Institute (CRI) at Florida Interna- tional University-May 23rd to 25th, 2013.1 At that time, the Cuban Foreign Investment Law had not been up- dated, the new U.S. policy towards Cuba-announced on December 17th 2014-was not in place, and the two countries were still pretty much at each other's throat, whereas now diplomatic relationships have been reestablished after over half of a century. Even if it is sheer nonsense to claim that nothing has changed in Cuba since Raul Castro took over from his ailing brother Fidel seven years ago, there is one thing that has not changed: the lack of precision regarding the nature and extent of the property rights a non-resident foreign inves- tor in Cuba-even one holding one of the new real estate investor visas2-gets when he or she "purchases" real estate in Cuba. -

TITLE COMMITMENT EXCEPTIONS for VIRGINIA the Attached Are Examples of Language Used in Standard Exceptions

TITLE COMMITMENT EXCEPTIONS FOR VIRGINIA The attached are examples of language used in standard exceptions. Please contact underwriting counsel if you have any questions. [access] Access 1 # Notwithstanding the Covered Risks in the Policy, the Company does not insure against any loss or damage by reason of lack of access to and from the property described in Schedule A. Access 2 # Rights of others in and to the use of the easement for ingress and egress described in Instrument No. _____. [acreage] # Exact acreage or volume of property described in Schedule A. [affirmative coverage for restrictive covenants] Aff Cov 1 # NOTE (as to Lender’s Policy only): The policy insures that the covenants have not been violated by any existing structures and a future violation will not cause a forfeiture or reversion of title. Note: providing this coverage means the title agent has reviewed the restrictions and can affirm there is not forfeiture or reversion of title provision. Aff Cov 2 # NOTE: Subject to the conditions and stipulations contained in the Policy, the Company hereby insures the insured against loss or damage by reason of the entry of a final court decree (that constitutes a final determination) from a court of competent jurisdiction divesting the lien of the insured Deed of Trust in whole or in part by reason of the aforesaid. Note: ORT underwriter approval needed before using this coverage. Aff Cov 3 # Subject to the Conditions and Stipulations contained in the Policy, the Company hereby insures the insured against loss or damage by reason of the enforcement or attempted enforcement of this judgment lien. -

Toward a Model Law of Estates and Future Interests

Toward a Model Law of Estates and Future Interests D. Benjamin Barros* Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................... 4 II. The Case for Reform ........................................................................ 7 A. The Bestiary of Estates and Future Interests .............................. 7 B. The Unnecessary Complexity of the Current System .............. 17 C. If It Ain’t (Completely) Broke, Why Fix It? ............................ 20 III. Two Mechanisms of Reform: Restatements v. Model Laws .......... 22 IV. Crafting a Model Law ..................................................................... 28 A. Initial Considerations ............................................................... 28 1. Naming Issues ................................................................... 29 2. Elimination of the Vestiges of Feudalism ......................... 30 3. Alienability of Present and Future Interests ...................... 30 4. Scope and Definitions of Present and Future Interests ...... 31 B. Present Possessory Interests ..................................................... 32 1. The Fee Simple Absolute .................................................. 32 2. Nonrecognition of Fee Tail and Fee Simple Conditional ........................................................................ 33 3. The Life Estate .................................................................. 34 4. The Tenancies .................................................................. -

A Reversion and a Remainder Distinguished

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 13 Fall 9-1-1959 A Reversion And A Remainder Distinguished Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation A Reversion And A Remainder Distinguished, 16 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 275 (1959), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol16/iss2/13 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1959] CASE COMMENTS IV. CONCLUSION Having pointed out what appear to be the major weaknesses in the majority's attempt to establish the existence of a duty, be it re- ciprocal, assumed, or statutory, the negligent performance of which would serve as a basis for imposing liability upon the defendant, it is submitted that the proper action for the Court of Appeals would have been to affirm the decision of the Appellate Division of the Su- preme Court. "To correct an indefensible situation is highly de- sirable. To correct one by the creation of another is equally unde- sirable."49 While it is true that the police department of New York is under a broad duty to protect the general public, this duty, under the present statutory provisions, does not inure to the individual members of the public so as to give them a cause of action against the City.