Disease Detection and Diagnosis Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communicable Disease Chart

COMMON INFECTIOUS ILLNESSES From birth to age 18 Disease, illness or organism Incubation period How is it spread? When is a child most contagious? When can a child return to the Report to county How to prevent spreading infection (management of conditions)*** (How long after childcare center or school? health department* contact does illness develop?) To prevent the spread of organisms associated with common infections, practice frequent hand hygiene, cover mouth and nose when coughing and sneezing, and stay up to date with immunizations. Bronchiolitis, bronchitis, Variable Contact with droplets from nose, eyes or Variable, often from the day before No restriction unless child has fever, NO common cold, croup, mouth of infected person; some viruses can symptoms begin to 5 days after onset or is too uncomfortable, fatigued ear infection, pneumonia, live on surfaces (toys, tissues, doorknobs) or ill to participate in activities sinus infection and most for several hours (center unable to accommodate sore throats (respiratory diseases child’s increased need for comfort caused by many different viruses and rest) and occasionally bacteria) Cold sore 2 days to 2 weeks Direct contact with infected lesions or oral While lesions are present When active lesions are no longer NO Avoid kissing and sharing drinks or utensils. (Herpes simplex virus) secretions (drooling, kissing, thumb sucking) present in children who do not have control of oral secretions (drooling); no exclusions for other children Conjunctivitis Variable, usually 24 to Highly contagious; -

797 Circulating Tumor DNA and Circulating Tumor Cells for Cancer

Medical Policy Circulating Tumor DNA and Circulating Tumor Cells for Cancer Management (Liquid Biopsy) Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History • Endnotes Policy Number: 797 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.04.141 Related Policies Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Cancer Risk Assessment of Prostate Cancer, #336 Policy1 Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Plasma-based comprehensive somatic genomic profiling testing (CGP) using Guardant360® for patients with Stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY when the following criteria have been met: Diagnosis: • When tissue-based CGP is infeasible (i.e., quantity not sufficient for tissue-based CGP or invasive biopsy is medically contraindicated), AND • When prior results for ALL of the following tests are not available: o EGFR single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions and deletions (indels) o ALK and ROS1 rearrangements o PDL1 expression. Progression: • Patients progressing on or after chemotherapy or immunotherapy who have never been tested for EGFR SNVs and indels, and ALK and ROS1 rearrangements, and for whom tissue-based CGP is infeasible (i.e., quantity not sufficient for tissue-based CGP), OR • For patients progressing on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). If no genetic alteration is detected by Guardant360®, or if circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is insufficient/not detected, tissue-based genotyping should be considered. Other plasma-based CGP tests are considered INVESTIGATIONAL. CGP and the use of circulating tumor DNA is considered INVESTIGATIONAL for all other indications. 1 The use of circulating tumor cells is considered INVESTIGATIONAL for all indications. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 22% Specialists in 2017 = 11%3

Medical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases Profile Updated December 2019 1 Table of Contents Slide . General Information 3-5 . Total number & number/100,000 population by province, 2019 6 . Number/100,000 population, 1995-2019 7 . Number by gender & year, 1995-2019 8 . Percentage by gender & age, 2019 9 . Number by gender & age, 2019 10 . Percentage by main work setting, 2019 11 . Percentage by practice organization, 2017 12 . Hours worked per week (excluding on-call), 2019 13 . On-call duty hours per month, 2019 14 . Percentage by remuneration method 15 . Professional & work-life balance satisfaction, 2019 16 . Number of retirees during the three year period of 2016-2018 17 . Employment situation, 2017 18 . Links to additional resources 19 2 General information Microbiology and infectious diseases focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases; thus, it is concerned with human illness due to micro-organisms. Since such disease can affect any and all organs and systems, this specialist must be prepared to deal with any region of the body. The specialty of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease consists primarily of four major spheres of activity: 1. the provision of clinical consultations on the investigation, diagnosis and treatment of patients suffering from infectious diseases; 2. the establishment and direction of infection control programs across the continuum of care; 3. public health and communicable disease prevention and epidemiology; 4. the scientific and administrative direction of a diagnostic microbiology laboratory. Source: Pathway evaluation program 3 General information Once you’ve completed medical school, it takes an additional 5 years of Royal College-approved residency training to become certified in medical microbiology and infectious disease. -

Diagnostic Tests Diagnostic Tests Attempt to Classify Whether Somebody Has a Disease Or Not Before Symptoms Are Present

community project encouraging academics to share statistics support resources All stcp resources are released under a Creative Commons licence stcp-rothwell-diagnostictests Diagnostic Tests Diagnostic tests attempt to classify whether somebody has a disease or not before symptoms are present. We are interested in detecting the disease early, while it is still curable. However, there is a need to establish how good a diagnostic test is in detecting disease. In this situation a 2x2 table similar to the below would be produced to test how effective a diagnostic test is at predicting the outcome of interest. A number of different measures can be calculated from this information. True Diagnosis Disease +ve Disease -ve Total Test Results +ve a b a+b -ve c d c+d a+c b+d N = This is the proportion of diseased individuals that are correctly Sensitivity: ( ) identified by the test as having the disease. (+ | ) + = This is the proportion of non-diseased individuals that Specificity: ( ) are correctly identified by the test as not having the disease. ( | ) + = This is the proportion − of individuals with Positive Predictive Value**: ( ) positive test results that are correctly diagnosed and actually have the disease. ( | + ) + = This is the proportion of individuals with Negative Predictive Value**: ( ) negative test results that are correctly diagnosed and do not have the disease. ( | + ) − © Joanne Rothwell Reviewer: Chris Knox University of Sheffield University of Sheffield Medical Statistics – diagnostic tests Positive Likelihood Ratio: = This gives a ratio of the test being positive + for patients with disease compared with those without disease. Aim to be much greater − than 1 for a good test. -

Burden of Disease: What Is It and Why Is It Important for Safer Food?

Burden of disease: what is it and why is it important for safer food? What is ‘burden of disease’? Burden of disease is concept that was developed in the 1990s by the Harvard School of Public Health, the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO) to describe death and loss of health due to diseases, injuries and risk factors for all regions of the world.1 The burden of a particular disease or condition is estimated by adding together: • the number of years of life a person loses as a consequence of dying early because of the disease (called YLL, or Years of Life Lost); and • the number of years of life a person lives with disability caused by the disease (called YLD, or Years of Life lived with Disability). Adding together the Years of Life Lost and Years of Life lived with Disability gives a single-figure estimate of disease burden, called the Disability Adjusted Life Year (or DALY). One DALY represents the loss of one year of life lived in full health (see text box for more explanation and examples). Looking at burden of disease using DALYs can reveal surprises about a population’s health. For example, the Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update suggests that neuropsychiatric conditions are the most important causes of disability in all regions of the world, accounting for around 33% of all years lived with disability among adults aged 15 years and over, but only 2.2% of deaths.2 Therefore while psychiatric disorders are not traditionally regarded as having a major impact on the health of populations, this picture is completely altered when the burden of disease is estimated using DALYs. -

In the Prevention of Occupational Diseases 94 7.1 Introduction

Report on the current situation in relation to occupational diseases' systems in EU Member States and EFTA/EEA countries, in particular relative to Commission Recommendation 2003/670/EC concerning the European Schedule of Occupational Diseases and gathering of data on relevant related aspects ‘Report on the current situation in relation to occupational diseases’ systems in EU Member States and EFTA/EEA countries, in particular relative to Commission Recommendation 2003/670/EC concerning the European Schedule of Occupational Diseases and gathering of data on relevant related aspects’ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Foreword .................................................................................................... 4 1.2 The burden of occupational diseases ......................................................... 4 1.3 Recommendation 2003/670/EC .................................................................. 6 1.4 The EU context .......................................................................................... 9 1.5 Information notices on occupational diseases, a guide to diagnosis .................................................................................................. 11 1.6 Objectives of the project ........................................................................... 11 1.7 Methodology and sources ........................................................................ 12 1.8 Structure of the report .............................................................................. 15 2 Developments -

Diabetic Foot and Gangrene

11 Diabetic Foot and Gangrene Jude Rodrigues and Nivedita Mitta Department of Surgery, Goa Medical College, India 1. Introduction “Early intervention in order to prevent potential disaster in the management of Diabetic foot is not only a great responsibility, but also a great opportunity” Despite advances in our understanding and treatment of diabetes mellitus, diabetic foot disease still remains a terrifying problem. Diabetes is recognized as the most common cause of non-traumatic lower limb amputation in the western world, with individuals over 20 times more likely to undergo an amputation compared to the rest of the population. There is growing evidence that the vascular contribution to diabetic foot disease is greater than was previously realised. This is important because, unlike peripheral neuropathy, Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease (PAOD) due to atherosclerosis, is generally far more amenable to therapeutic intervention. PAOD, has been demonstrated to be a greater risk factor than neuropathy in both foot ulceration and lower limb amputation in patients with diabetes. Diabetes is associated with macrovascular and microvascular disease. The term peripheral vascular disease may be more appropriate when referring to lower limb tissue perfusion in diabetes, as this encompasses the influence of both microvascular dysfunction and PAOD. Richards-George P. in his paper about vasculopathy on Jamaican diabetic clinic attendees showed that Doppler measurements of ankle/brachial pressure index (A/BI) revealed that 23% of the diabetics had peripheral occlusive arterial disease (POAD) which was mostly asymptomatic. This underscores the need for regular Doppler A/BI testing in order to improve the recognition, and treatment of POAD. -

Remodeling Clinical Examinations Using OWL∗

Representing Knowledge in Oral Medicine – Remodeling Clinical Examinations Using OWL∗ Technical Report HS-IKI-TR-06-009 School of Humanities and Informatics, University of Sk¨ovde Marie Gustafsson [email protected] School of Humanities and Informatics University of Sk¨ovde, Box 408, SE-541 28 Sk¨ovde, Sweden Department of Computer Science and Engineering Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96 G¨oteborg, Sweden Abstract This report describes the remodeling of the representation of clinical examinations in oral medicine, from the previous proprietary format used by the MedView project, to using the World Wide Web Consortium’s recommendations Web Ontology Language (OWL) and Resource Description Framework (RDF). This includes the representation of (1) ex- amination templates, (2) lists of values that can be included in individual examination records, and (3) aggregates of such values used for e.g., analyzing and visualizing data. It also includes the representation of (4) individual examination records. We describe how OWL and RDF are used to represent these different knowledge components of MedView, along with the design decisions made in the remodeling process. These design decisions are related to, among other things, whether or not to use the constructs of domain and range, appropriate naming in URIs, the level of detail to initially aim for, and appropriate use of classes and individuals. A description of how these new representations are used in the previous applications and code base is also given, as well as their use in the Swedish Oral Medicine Web (SOMWeb) online community. We found that OWL and RDF can be used to address most, but not all, of the requirements we compiled based on the limitations of the MedView knowledge model. -

Regulations for Disease Reporting and Control

Department of Health Regulations for Disease Reporting and Control Commonwealth of Virginia State Board of Health October 2016 Virginia Department of Health Office of Epidemiology 109 Governor Street P.O. Box 2448 Richmond, VA 23218 Department of Health Department of Health TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I. DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................................................... 1 12 VAC 5-90-10. Definitions ............................................................................................. 1 Part II. GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................................... 8 12 VAC 5-90-20. Authority ............................................................................................... 8 12 VAC 5-90-30. Purpose .................................................................................................. 8 12 VAC 5-90-40. Administration ....................................................................................... 8 12 VAC 5-90-70. Powers and Procedures of Chapter Not Exclusive ................................ 9 Part III. REPORTING OF DISEASE ............................................................................................. 10 12 VAC 5-90-80. Reportable Disease List ....................................................................... 10 A. Reportable disease list ......................................................................................... 10 B. Conditions reportable by directors of -

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

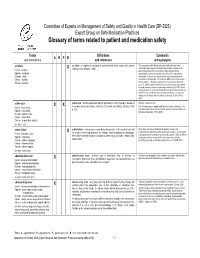

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision Volume 2 Instruction manual 2010 Edition WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. - 10th revision, edition 2010. 3 v. Contents: v. 1. Tabular list – v. 2. Instruction manual – v. 3. Alphabetical index. 1.Diseases - classification. 2.Classification. 3.Manuals. I.World Health Organization. II.ICD-10. ISBN 978 92 4 154834 2 (NLM classification: WB 15) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.