Phosphorus Dynamics in Selected Wetlands and Streams of the Lake Okeechobee Basin *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

An Historical Perspective on the Kissimmee River Restoration Project

ing of 14 km of river channel, and removal of two water An Historical control structures and associated levees. Restoration of the Kissimmee River ecosystem will result in the reestablish ment of 104 km2 of river-floodplain ecosystem, including Perspective on the 70 km of river channel and 11,000 ha of wetland habitat, which is expected to benefit over 320 species of fish and Kissimmee River wildlife. Restoration Project Background he Kissimmee River basin is located in central Florida Tbetween the city of Orlando and lake Okeechobee Joseph W. Koebel, Jr.1 within the Coastal Lowlands physiographic province. It con sists of a 4229-km2 upper basin, which includes Lake Kis Abstract simmee and 18 smaller lakes ranging in size from a few hec tares to 144 km2, and a 1,963-km2 lower basin, which This paper reviews the events leading to the channeliza includes the tributary watersheds (excluding Lake Istok tion of the Kissimmee River, the physical, hydrologic, and poga) of the Kissimmee River between lake Kissimmee and biological effects of channelization, and the restoration lake Okeechobee. The physiography of the region includes movement. Between 1962 and 1971, in order to provide the Osceola and Okeechobee Plains and the Lake Wales flood control for central and southern florida, the 166 ridge of the Wicomico shore (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers km-Iong meandering Kissimmee River was transformed 1992). into a 90 km-Iong, 10 meter-deep, 100 meter-wide canal. Prior to channelization, the Kissimmee River meandered Channelization and transformation of the Kissimmee River approximately 166 km within a 1.5-3-km-wide floodplain. -

LOWRP Draft PIR/EIS Annex C

COMPREHENSIVE EVERGLADES RESTORATION PLAN LAKE OKEECHOBEE WATERSHED RESTORATION PROJECT DRAFT INTEGRATED PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT July 2018 Annex C Annex C Draft Project Operating Manual ANNEX C DRAFT PROJECT OPERATING MANUAL LOWRP Draft PIR and EIS July 2018 Annex C-i Annex C Draft Project Operating Manual This page intentionally left blank. LOWRP Draft PIR and EIS July 2018 Annex C-ii Annex C Draft Project Operating Manual Table of Contents C DRAFT PROJECT OPERATING MANUAL .................................................................... C-1 C.1 General Project Purposes, Goals, Objectives, and Benefits ................................... C-1 C.2 Project Features .................................................................................................. C-1 C.2.1 Existing Features ..................................................................................... C-2 C.2.2 Proposed Features .................................................................................. C-3 C.3 Project Relationships ........................................................................................... C-6 C.4 Major Constraints ................................................................................................ C-7 C.4.1 Paradise run ............................................................................................ C-8 C.4.2 Existing Legal Users, Levels of Flood Damage Reduction, and Water Quality ................................................................................................... -

Environmental Plan for Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades Tributaries (EPKOET)

Environmental Plan for Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades Tributaries (EPKOET) Stephanie Bazan, Larissa Gaul, Vanessa Huber, Nicole Paladino, Emily Tulsky April 29, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY…………………...………………………………………..4 2. MISSION STATEMENT…………………………………....…………………………………7 3. GOVERNANCE……………………………………………………………………...………...8 4. FEDERAL, STATE, AND LOCAL POLICIES…………………………………………..…..10 5. PROBLEMS AND GOALS…..……………………………………………………………....12 6. SCHEDULE…………………………………....……………………………………………...17 7. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS…………………………………………....17 REFERENCES…………………………………………………………..……………………....18 2 LIST OF FIGURES Figure A. Map of the Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades Watershed…………………………...4 Figure B. Phosphorus levels surrounding the Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades Watershed…..5 Figure C. Before and after backfilling of the Kissimmee river C-38 canal……………………….6 Figure D. Algae bloom along the St. Lucie River………………………………………………...7 Figure E. Florida’s Five Water Management Districts………………………………………........8 Figure F. Three main aquifer systems in southern Florida……………………………………....14 Figure G. Effect of levees on the watershed………………………………………...…………...15 Figure H. Algal bloom in the KOE watershed…………………………………………...………15 Figure I: Canal systems south of Lake Okeechobee……………………………………………..16 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Primary Problems in the Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades watershed……………...13 Table 2: Schedule for EPKOET……………………………………………………………….…18 3 1. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY The Kissimmee Okeechobee Everglades watershed is an area of about -

Joint Public Workshop for Minimum Flows and Levels Priority Lists and Schedules for the CFWI Area

Joint Public Workshop for Minimum Flows and Levels Priority Lists and Schedules for the CFWI Area St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) September 5, 2019 St. Cloud, Florida 1 Agenda 1. Introductions and Background……... Don Medellin, SFWMD 2. SJRWMD MFLs Priority List……Andrew Sutherland, SJRWMD 3. SWFWMD MFLs Priority List..Doug Leeper, SWFWMD 4. SFWMD MFLs Priority List……Don Medellin, SFWMD 5. Stakeholder comments 6. Adjourn 2 Statutory Directive for MFLs Water management districts or DEP must establish MFLs that set the limit or level… “…at which further withdrawals would be significantly harmful to the water resources or ecology of the area.” Section 373.042(1), Florida Statutes 3 Statutory Directive for Reservations Water management districts may… “…reserve from use by permit applicants, water in such locations and quantities, and for such seasons of the year, as in its judgment may be required for the protection of fish and wildlife or the public health and safety.” Section 373.223(4), Florida Statutes 4 District Priority Lists and Schedules Meet Statutory and Rule Requirements ▪ Prioritization is based on the importance of waters to the State or region, and the existence of or potential for significant harm ▪ Includes waters experiencing or reasonably expected to experience adverse impacts ▪ MFLs the districts will voluntarily subject to independent scientific peer review are identified ▪ Proposed reservations are identified ▪ Listed water bodies that have the potential to be affected by withdrawals in an adjacent water management district are identified 5 2019 Draft Priority List and Schedule ▪ Annual priority list and schedule required by statute for each district ▪ Presented to respective District Governing Boards for approval ▪ Submitted to DEP for review by Nov. -

Habitat Use by and Dispersal of Snail Kites in Florida During Drought Conditions

HABITAT USE BY AND DISPERSAL OF SNAIL KITES IN FLORIDA DURING DROUGHT CONDITIONS STEVENR. BEISSINGERAND JEANE. TAKEKAWA School of Natural Resources, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 and Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, Rt. 1, Box 278, Boynton Beach, Florida 33437. Although originally ranging over most of peninsular Florida (Howell 1932), Snail (Everglade) Kites (Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus) have been restricted in recent years mostly to three areas in southern Florida: the western marshes of Lake Okeecho- bee; Conservation Area (CA) 3A; and CA2 (Sykes 1978, 1979, 1983). Severe drought in southern Florida in 1981 dried nearly all wetlands inhabited by kites. Water levels at Lake Okeechobee were at record lows (2.9 m msl) in July and August, drying 99% of the wetland area. Water remained about 1.5 m below scheduled levels until June 1982 when it quickly rose as a result of heavy summer rains. Only perimeter canals contained surface water from May- August 1981 in CA3A and March-August 1981 in CA2 when Tropi- cal Storm Dennis (16-19 August) replenished surface water sup- plies. After reaching scheduled levels in September 1981, water de- creased again until CA2 dried out in February and CA3A in early May 1982. In late May 1982, surface water rose quickly again to near normal levels. As a result of habitat unavailability caused by this drought, Snail Kites dispersed throughout the Florida peninsula in search of foraging habitats with apple snails (Ponzacea paludosa) , practically their sole source of food (for exceptions see Sykes and Kale 1974, Woodin and Woodin 1981, Takekawa and Beissinger 1983, Beis- singer in prep.). -

Chapter 1: the Everglades to the 1920S Introduction

Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s Introduction The Everglades is a vast wetland, 40 to 50 miles wide and 100 miles long. Prior to the twentieth century, the Everglades occupied most of the Florida peninsula south of Lake Okeechobee.1 Originally about 4,000 square miles in extent, the Everglades included extensive sawgrass marshes dotted with tree islands, wet prairies, sloughs, ponds, rivers, and creeks. Since the 1880s, the Everglades has been drained by canals, compartmentalized behind levees, and partially transformed by agricultural and urban development. Although water depths and flows have been dramatically altered and its spatial extent reduced, the Everglades today remains the only subtropical ecosystem in the United States and one of the most extensive wetland systems in the world. Everglades National Park embraces about one-fourth of the original Everglades plus some ecologically distinct adjacent areas. These adjacent areas include slightly elevated uplands, coastal mangrove forests, and bays, notably Florida Bay. Everglades National Park has been recognized as a World Heritage Site, an International Biosphere Re- serve, and a Wetland of International Importance. In this work, the term Everglades or Everglades Basin will be reserved for the wetland ecosystem (past and present) run- ning between the slightly higher ground to the east and west. The term South Florida will be used for the broader area running from the Kississimee River Valley to the toe of the peninsula.2 Early in the twentieth century, a magazine article noted of the Everglades that “the region is not exactly land, and it is not exactly water.”3 The presence of water covering the land to varying depths through all or a major portion of the year is the defining feature of the Everglades. -

Draft Okeechobee Waterway Master Plan Update and Integrated

Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan Update DRAFT Draft Okeechobee Waterway Master Plan Update and Integrated Environmental Assessment 23 July 2018 Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan Update DRAFT This page intentionally left blank. Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan Update DRAFT Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan DRAFT 23 July 2018 The attached Master Plan for the Okeechobee Waterway Project is in compliance with ER 1130-2-550 Project Operations RECREATION OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE GUIDANCE AND PROCEDURES and EP 1130-2-550 Project Operations RECREATION OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE POLICIES and no further action is required. Master Plan is approved. Jason A. Kirk, P.E. Colonel, U.S. Army District Commander i Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan Update DRAFT [This page intentionally left blank] ii Okeechobee Waterway Project Master Plan Update DRAFT Okeechobee Waterway Master Plan Update PROPOSED FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT FOR OKEECHOBEE WATERWAY MASTER PLAN UPDATE GLADES, HENDRY, MARTIN, LEE, OKEECHOBEE, AND PALM BEACH COUNTIES 1. PROPOSED ACTION: The proposed Master Plan Update documents current improvements and stewardship of natural resources in the project area. The proposed Master Plan Update includes current recreational features and land use within the project area, while also including the following additions to the Okeechobee Waterway (OWW) Project: a. Conversion of the abandoned campground at Moore Haven West to a Wildlife Management Area (WMA) with access to the Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail (LOST) and day use area. b. Closure of the W.P. Franklin swim beach, while maintaining the picnic and fishing recreational areas with potential addition of canoe/kayak access. This would entail removing buoys and swimming signs and discontinuing sand renourishment. -

3.1 Wildlife Habitat

1 Acknowledgements The Conservancy of Southwest Florida gratefully acknowledges the Policy Division staff and interns for their help in compiling, drafting, and revising the first Estuaries Report Card , including Jennifer Hecker, the report’s primary author. In addition, the Conservancy’s Science Division is gratefully acknowledged for its thorough review and suggestions in producing the finished report. The Conservancy would also like to thank Joseph N. Boyer, Ph. D. (Associate Director and scientist from Florida International University – Southeast Environmental Research Center), Charles “Chuck” Jacoby, Ph. D. (Estuarine Ecology Specialist from the University of Florida), S. Gregory Tolley, Ph. D. (Professor of Marine Science and Director of the Coastal Watershed Institute from Florida Gulf Coast University) as well as Lisa Beever, Ph. D. (Director of the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program) for their review and/or support of this first edition of the Estuaries Report Card. In addition, special thanks goes to the Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program for its generous financial contribution to the 2005 report. The Conservancy thanks the following for their generous financial support in making this report possible: Anonymous supporter (1); Banbury Fund; Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation; and The Stranahan Foundation Photo Credits: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce, cover image South Florida Water Management District, pages 4, 6, 23, 36, 41, 63, 105, 109, 117, 147, 166, 176 The recommendations listed herein are those of the Conservancy of Southwest Florida and do not necessarily reflect the view of our report sponsors. © 2005 Conservancy of Southwest Florida, Inc. The Conservancy of Southwest Florida is a non-profit organization. -

Everglades to Okeefenokee – a Thousand Miles Through the Heart of Florida

FLORIDA WILDLIFE CORRIDOR EXPEDITION: EVERGLADES TO OKEEFENOKEE – A THOUSAND MILES THROUGH THE HEART OF FLORIDA The vision of the Florida Wildlife Corridor is to connect natural lands and waters throughout peninsular Florida, from the Everglades to Okeefenokee in southeast Georgia. Despite extensive fragmentation of the landscape in recent decades, a statewide network of connected natural areas is still possible. The first step is raising awareness about the fleeting opportunity we have to connect natural and rural landscapes in order to protect the waters that sustain us, the working farms and ranches that feed us, the forests that clean our air, and the combined habitat these lands provide for Florida’s diverse wildlife, including panthers and black bears. Our goal is to increase public awareness for the Corridor idea through a broad-reaching media campaign, with the Florida Wildlife Corridor Expedition as the center of the outreach strategy. January 17, 2012 marks the kick off the 1000 mile expedition over a 100 day period to increase public awareness and generate support for the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Photographer Carlton Ward Jr, bear biologist Joe Guthrie, conservationist Mallory Lykes Dimmitt and filmmaker Elam Stoltzfus will trek from the Everglades National Park toward Okefenokee National Forest in southern Georgia. They will traverse the wildlife FLORIDA WILDLIFE habitats, watersheds and participating working farms and ranches, which comprise CORRIDOR the Florida Wildlife Corridor opportunity area. KEY ISSUES: The team will document the corridor through photography, video, radio reports, • Protecting and restoring dispersal and daily updates on social media networks, and a host of activities for reporters, migration corridors essential for the landowners, celebrities, conservationists, politicians and other guests. -

Ellen Peterson December 5, 1923 - October 14, 2011

Ellen Peterson December 5, 1923 - October 14, 2011 Ellen Peterson nee Salisbury 87, of Estero, Florida passed away on October 14th, 2011. She was born in Georgia on December 5, 1923. She is survived by a niece, Rhonda Romano (Thomas) of St. Petersburg, Florida, a nephew, James Davis (Barb) of Grand Rapids Michigan, and Grand nieces Megan and Michelle. She was predeceased by a sister Mary Alice Davis. She graduated from the University of Georgia in 1945 with a degree in Chemistry and she received her Masters in counseling in 1963 from Appalachia State. She c ame to Southwest Florida shortly afterwards, and served as the Director of the Counseling Center at Edison College for many years. She also became a fierce advocate for our wildlife and wild places. Ellen was a warrior when it came to the environment; she cared deeply and devoted her life to saving the planet and protecting Mother Earth. She served on many boards and advisory committees such as: the Agency for Bay Management, the Environmental Confederation of Southwest Florida, Save Our Creeks, the Responsible Growth Management Coalition, The Everglades Committee, the Environmental Peace and Education Center and the Sierra Club's Calusa Group. Ellen founded the Calusa group over 30 years ago and remained the chairperson until her death. The Agency for Bay Management was formed as a result of a lawsuit about where FGCU would be built; Ellen was the only member who refused to sign off on the settlement agreement. Ellen spoke at countless county commission hearings, and her presence was powerful, always intelligently informed, and unrelenting. -

Appendix 1 U.S

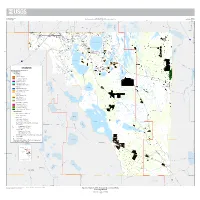

U.S. Department of the Interior Prepared in cooperation with the Appendix 1 U.S. Geological Survey Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Office of Agricultural Water Policy Open-File Report 2014−1257 81°45' 81°30' 81°15' 81°00' 80°45' 524 Jim Creek 1 Lake Hart 501 520 LAKE 17 ORANGE 417 Lake Mary Jane Saint Johns River 192 Boggy Creek 535 Shingle Creek 519 429 Lake Preston 95 17 East Lake Tohopekaliga Saint Johns River 17 Reedy Creek 28°15' Lake Lizzie Lake Winder Saint Cloud Canal ! Lake Tohopekaliga Alligator Lake 4 Saint Johns River EXPLANATION Big Bend Swamp Brick Lake Generalized land use classifications 17 for study purposes: Crabgrass Creek Land irrigated Lake Russell Lake Mattie Lake Gentry Row crops Lake Washington Peppers−184 acresLake Lowery Lake Marion Creek 192 Potatoes−3,322 acres 27 Lake Van Cantaloupes−633 acres BREVARD Lake Alfred Eggplant−151 acres All others−57 acres Lake Henry ! UnverifiedLake Haines crops−33 acres Lake Marion Saint Johns River Jane Green Creek LakeFruit Rochelle crops Cypress Lake Blueberries−41 acres Citrus groves−10,861 acres OSCEOLA Peaches−67 acresLake Fannie Lake Hamilton Field Crops Saint Johns River Field corn−292 acres Hay−234 acres Lake Hatchineha Rye grass−477 acres Lake Howard Lake 17 Seeds−619 acres 28°00' Ornamentals and grasses Ornamentals−240 acres Tree nurseries−27 acres Lake Annie Sod farms−5,643Lake Eloise acres 17 Pasture (improved)−4,575 acres Catfish Creek Land not irrigated Abandoned groves−4,916 acres Pasture−259,823 acres Lake Rosalie Water source Groundwater−18,351 acres POLK Surface water−9,106 acres Lake Kissimmee Lake Jackson Water Management Districts irrigated land totals Weohyakapka Creek Tiger Lake South Florida Groundwater−18,351 acres 441 Surface water−7,596 acres Lake Marian St.