Vol. XLVII No. 1, Jan.-Dec 2012 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia

A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia Regional Framework, Literature Review and Country Case Studies Centre for Advocacy and Research New Delhi, India Centre for Advocacy and Research A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia Regional Framework, Literature Review and Country Case Studies Centre for Advocacy and Research New Delhi, India i CFAR Research Team Akhila Sivadas Prashant Jha Aarthi Pai Sambit Kumar Mohanty Pankaj Bedi V. Padmini Devi CFAR 2012–13 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or UN Member States. A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, ii Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia List of Acronyms and Abbreviations AALI Association for Advocacy and Legal DGHS Directorate General of Health Services Initiatives DIC Drop-in-centre AAS Ashar Alo Society DivA Diversity in Action (project) AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome DLLG District Level Lawyers Group amfAR The Foundation for AIDS Research ESCAP (United Nations) Economic and Social AMU Aligarh Muslim University Commission for Asia Pacific APCOM Asia Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual FGD Focus Group Discussion Health FHI Family Health International APTN Asia Pacific Transgender Network FPAB Family Planning Association of ART Anti-Retroviral Therapy Bangladesh ARV Anti-Retroviral Vaccine FPAN Family Planning -

Bangladesh Report

BENCHMARKING THE DRAFT UN PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON THE ELIMINATION OF (CASTE) DISCRIMINATION BASED ON WORK AND DESCENT Benchmarking the Draft UN Principles and Guidelines on the Elimination of (Caste) Discrimination based on Work and Descent BANGLADESH REPORT Mohammad Nasir Uddin Bangladesh Dalit and Excluded Rights Movement (BDERM) Nagorik Uddyog 1 BENCHMARKING THE DRAFT UN PRINCIPLES AND GUIDELINES ON THE ELIMINATION OF (CASTE) DISCRIMINATION BASED ON WORK AND DESCENT Benchmarking the Draft UN Principles and Guidelines on the Elimination of (Caste) Discrimination based on Work and Descent BANGLADESH REPORT © Nagorik Uddyog- Bangladesh Dalit and Excluded Rights Movement Any section of this report may be reproduced without prior permission of Nagorik Uddyog for public interest purpose with appropriate acknowledgement Study Conducted and report written by Mohammad Nasir Uddin Report Edited by Dr. Jayshree P. Mangubhai Introduction by Aloysius Irudayam SJ Study Team Zakir Hossain Afsana Binte Amin Md. Abdullah-Al Istiaque Mahmud Ishrat Shabnam Joyeeta Hossain Sheikh Md. Jamal International Study Coordinator Dr. Jayshree P. Mangubhai National Study Coordinator Afsana Binte Amin Cover Barek Hossain Mithu Published by Nagorik Uddyog, 8/14, Block-B, Lalmatia, Dhaka-1207 E-mail: [email protected], Website: nuhr.org and Bangladesh Dalit and Excluded Rights Movement (BDERM) 5/1, Block-E, lalmatia, Dhaka-1207, www.bderm.org Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Nagorik Uddyog-BDERM and can in no way be taken -

Media Release: Pakistan

International JACQUELINE PARK IFJ Asia-Pacific Director Federation ELISABETH COSTA of Journalists General Secretary Situation Report: Bangladesh, December 2012 Journalism in the Political Crossfire The deeply polarising effect of politics in Bangladesh has been felt in various domains, the media included. As Bangladesh prepares for another round of general elections to the national parliament at the end of 2013, political discord and disharmony are rising. The years since the last general elections in 2008 have been politically stable since the Awami League (AL), the party that led the country’s movement for liberation from Pakistan, has secured alongside its allies, an impregnable majority in parliament. But there has not been any manner of political concord. Opposition boycotts of the proceedings of parliament and allegations of unfair pressures on political and civil society elements inclined towards the opposition, have been frequent. In June 2011, the Government of Sheikh Hasina Wajed piloted the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution through Bangladesh’s parliament, providing another potential flashpoint for acrimony as elections near. Among other things, the Fifteenth Amendment does away with the process of conducting national elections under a neutral caretaker government. It reaffirms Islam as state religion, but then enshrines the values of secularism and freedom of faith. It officially raises Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to the status of “father of the nation”, mandates that his portraits will be displayed at key sites of the Bangladeshi state and the offices of its main functionaries, and incorporates into the official text of the constitution, two historic speeches that he made in March 1971 as Bangladesh broke away from Pakistan. -

January 2011.Pdf (611.0Kb)

2011/january BRACU Board of Trustees meeting held The first meeting of the Board of Trustees, BRAC University (BRACU) was held at the conference room of the university on January 26, 2011. Sir Fazle Hasan Abed KCMG, Chairperson, BRAC and Board of Trustees, BRACU chaired the meeting. Trustees Board Members Professor Ainun Nishat, Vice Chancellor, BRACU Professor Md. Golam Samdani Fakir, Pro-VC, BRACU, Mr. Faruq Ahmed Choudhury, Advisor, BRAC, Professor Dilara Chowdhury, Former Professor, Department of Government and Politics, Jahangir Nagar University, Ms. Rasheda K. Chowdhury, Executive Director, Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), Ms. Tamara Hasan Abed, Director, Aarong, AAF, BDFP, Mr. Sukendra Kumar Sarkar, Treasurer, BRACU and Mr. Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury, Registrar, BRACU were present in the meeting. Visit of Vice Chancellor of South Asian University Professor G.K. Chadda, Vice Chancellor of South Asian University (SAU), Delhi, along with Professor Saxena of the same University called on Professor Ainun Nishat, VC, BRAC University and met the senior faculty of the University on 3 February 2011. Professor Ainun Nishat welcomed the honoured guests and explained to them the present position and future plan of BRAC University. Professor Chadda gave a presentation covering the vision, mission, current activities and future plans for the SAU. He hoped that SAU and BRACU will be able to explore areas of mutual cooperation and will benefit from each others' resources. Professor Nishat reciprocated the feelings and hoped that the two Universities work out specific areas where mutually beneficial academic programmes could be chalked out. AIT President visited BRACU Professor Said Iradnoust, President of Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), Bangkok, Thailand visited BRAC University on 16 January 2011. -

Ecosystems for Life: a Bangladesh-India

Ecosystems for Life: A Bangladesh–India Initiative External Review Report Submitted to: IUCN Prepared by: Randal Glaholt, M.E.Des Julian Gonsalves, PhD. Donald Macintosh, PhD. August, 2014 External Review – IUCN Ecosystems for Life: a Bangladesh – India Initiative August 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Ecosystems for Life: A Bangladesh – India Initiative (Dialogue for Sustainable Management of Trans-boundary Water Regimes in South Asia) is an attempt to develop a neutral platform among key elements of civil society for discussing the management of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna (GBM) rivers shared by both countries. The Ecosystems For Life (E4L) Project commenced in 2010, and received its entire USD 6.4 million budget from The Minister for Development Cooperation of the Netherlands. The project was scheduled initially to run from February 1, 2010 until July 31, 2014; however, in November 2013, the project requested and was granted a five months extension to December 31, 2014. Through IUCN- facilitated collaborative deliberations, the PAC chose to focus on five major thematic areas: food security, water productivity and poverty; impacts of climate change; environmental security; trans-boundary inland navigation; and biodiversity conservation. The E4L project used four tools to achieve its goal and objectives: creation of formal dialogue opportunities; facilitating joint research; development of a shared knowledge base on water related resources; and capacity-building through training, exposure visits, communication, publications and dissemination. The external review process engaged a three-person team of independent consultants who had no prior direct or indirect involvement with E4L. The review process involved a combination of interviews with E4L project staff and E4L participants in both Bangladesh and India , as well as review of the project documentation. -

A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia

A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia Regional Framework, Literature Review and Country Case Studies Centre for Advocacy and Research New Delhi, India Centre for Advocacy and Research A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia Regional Framework, Literature Review and Country Case Studies Centre for Advocacy and Research New Delhi, India i CFAR Research Team Akhila Sivadas Prashant Jha Aarthi Pai Sambit Kumar Mohanty Pankaj Bedi V. Padmini Devi CFAR 2012–13 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or UN Member States. A Framework for Media Engagement on Human Rights, ii Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in South Asia List of Acronyms and Abbreviations AALI Association for Advocacy and Legal DGHS Directorate General of Health Services Initiatives DIC Drop-in-centre AAS Ashar Alo Society DivA Diversity in Action (project) AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome DLLG District Level Lawyers Group amfAR The Foundation for AIDS Research ESCAP (United Nations) Economic and Social AMU Aligarh Muslim University Commission for Asia Pacific APCOM Asia Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual FGD Focus Group Discussion Health FHI Family Health International APTN Asia Pacific Transgender Network FPAB Family Planning Association of ART Anti-Retroviral Therapy Bangladesh ARV Anti-Retroviral Vaccine FPAN Family Planning -

Impact of the Exchange Rate Regime Change on the Value of Bangladesh Currency A

Impact of the Exchange Rate Regime Change on the Value of Bangladesh Currency a Asad Karim Khan Priyo* Abstract Two distinctively different exchange rate regimes have been in place in Bangladesh – a fixed exchange rate regime from January 1972 – May 2003 and a floating exchange rate regime since June 2003. Since the change in regime, the value of Bangladesh currency ‘Taka’ has fallen by more than 20% against the US Dollar during a period when the US Dollar itself has been losing value. The objective of this paper is to analyze whether the exchange rate regime change in Bangladesh has had any significant impact on the value of its currency i.e. whether the regime change is associated with the loss in the value of Taka. The fact that during the fixed regime, Bangladesh pursued an active exchange rate policy as reflected by the policies of Bangladesh Bank during that period is what makes the question worth asking. In one way, this paper tests the efficiency of Bangladesh Bank in terms of pricing its currency during the fixed regime. In the process, the paper also tries to identify the variables that play important roles in determining the exchange rate of Taka. In order to provide context; the exchange rate system in Bangladesh – its past, its present; the causes of the change in the system and a comparative analysis of the systems have been briefly discussed. a Published in Social Science Review (Faculty of Social Science, University of Dhaka) 26, no. 1 (June 2009): 185- 214. *PhD Candidate, Department of Economics, University of Toronto; Lecturer, School of Business, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh (On study leave). -

FINAL Annual Report 2006.Qxd

INDIA SRI LANKA PAKISTAN SAARC MALDIVES HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2006 NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2006 S A R C ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS edited by: Suhas Chakma SAARC Human Rights Report 2006 Edited by: Suhas Chakma Director, Asian Centre for Human Rights Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Phone/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published 2006 © Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2006. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. Photos: Courtesy - India (The Tribune, India, 26 April 2005 at http://www.tribuneindia.com/2005/20050426/punjab.htm) Sri Lanka (http://img406.imageshack.us/img406/1469/r28473599251cy.jpg) Pakistan (BBC News, 3 March 2005 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4315491.stm) Maldives (Minivannews.com; http://www.minivannews.com/photos/12-13/pages/bf%20(24)_jpg.htm) Nepal (Kantipur Online, Nepal at http://www.kantipuronline.com/admin/nepfrontimg/kpr2005-7-25.jpg) Bhutan (http://ec.europa.eu/echo/images/photos/nepal/nepal_01.jpg) Bangladesh (http://www.albd.org/newsletter/2004/hartal_women_torture.jpg) ISBN : 81-88987-15-8 Price Rs. 745/- SAARC Human Rights Report 2006 iii Table of Contents Preface . .1 1. SAARC Human Rights Violators Index 2006 I. Indicators for ranking . .3 II. Explanation about ranking . .3 II. SAARC Human Rights Violators Index . .4 Bangladesh: Rank 1st . .4 Bhutan: Rank 2nd . .6 Nepal: Rank 3rd . -

Human Rights Defenders and Journalists at Risk (

n° 421/2 June 2005 International Federation for Human Rights Report International Fact Finding Mission Speaking out Makes of You a Target Human Rights Defenders and Journalists at Risk Grave Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Bangladesh Introduction . 4 I. History and Politics of Bangladesh . 5 II. Freedom of expression . 7 III. Freedom of association1 . 17 IV. Conclusions and Recommendations . 24 Annex 1: Persons Met by the Delegation, Bangladesh 2004 . 26 Annex 2: Follow up Mission to Bangladesh, 25-28 September 2005. 27 1. This section of the report takes place in the framework of the joint programme of FIDH and OMCT, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders. Speaking out Makes of You a Target Human Rights Defenders and Journalists at Risk Summary Introduction. 4 I. History and Politics of Bangladesh . 5 II. Freedom of expression . 7 1. International legal framework . 8 2. Legislative texts pertaining to freedom of expression and of information, or used to limit it . 8 3. The situation of journalists. 11 a. General pattern of repression . 11 b. Using the financial leverage against the media. 15 4. Intimidations and threats faced by academics . 16 III. Freedom of association1 . 17 1. General remarks . 17 2. Legal framework for NGO activities . 17 3. Current situation of NGOs . 19 a. PROSHIKA. 19 b. PRIP Trust . 21 c. IVS. 22 d. ADAB. 22 e. NGOs active on the rights of minorities . 22 IV. Conclusions and Recommendations. 24 Annex 1: Persons Met by the Delegation, Bangladesh 2004. 26 Annex 2: Follow up Mission to Bangladesh, 25-28 September 2005 . -

Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore

(c) Copyright 2008 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Editors Werner vom Busch Alastair Carthew Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. ISBN 978-981-08-2423-5 Design and Layout TimeEdge Publishing Pte Ltd 10 Anson Road 15-14 International Plaza Singapore 079903 www.tepub.com CONTENTS The Asian Media Project of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Foreword by Werner vom Busch 5 Director Asia Media Programme Overview of Asian Media by Alastair Carthew 6 Country Listing BANGLADESH by Sayeed Zayadul Ahsan and Major Media Listing Shameem Mahmud An Assessment 11 Print 14 Radio 27 TV 28 CAMBODIA by John Maloy Major Media Listing An Assessment 33 Print 36 TV and Radio 48 Other Media 58 CHINA by Oliver Radtke Major Media Listing An Assessment 57 Print 62 TV and Radio 69 INDIA by Katha Kartiki Major Media Listing An Assessment 75 Print 79 TV and Radio 99 Other Media 108 INDONESIA by Ignatius Haryanto Major Media Listing An Assessment 111 Print 116 TV 118 Radio 120 KOREA by Kim Myong-sik Major Media Listing An Assessment 121 Print 125 TV and Radio 134 Other Media 136 Country Listing MALAYSIA by Sharmin Parameswaran Major Media Listing An Assessment 139 Print 142 TV and Radio 150 MYANMAR by Stuart Deed Major Media Listing An Assessment 155 Print 160 TV and Radio -

Judgment Sayedee

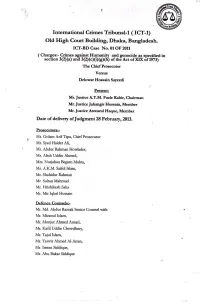

International Crimes Tribunal-l ( ICT-I) Old High Court Building, Dhaka, Bangladesh. ICT-BD Case No.01OF 2011 (' Charges:- Crimes against Humanity and genocide as soecified in secEon 3Q)@) anE 3(2)(cXr)(gXti) of thEAct of XIX rirreZll The Chief Prosecutor Vercus Delowar Hossain Sayeedi Prcsent: Mt. justice A.T.M. Fazle Kabir, Chairman Mr. Justice Jahangir Hossain, Member Mr. Justice Anwad Haque, Member Date of delivery ofJudgrnent 28 February, ?fll3. Pfosecutofs:- Mr. Golam Arif Tipu, Chief Prosecutor i Mr. Syed HaiderAli, Mr. Abdur Rahman Howlader, Mr. Altab Uddin Ahmed, Mrs. Nurjahan Begum Mrkt , Mr. A.K.M. Saifirl Islam, Mr. Shahidur Rahman Mr. Sulan Mahmud Mr. Hrishikesh Saha Mr. Mir Iqbal Hossain Defence Counsels:- Mr. Md. Abdut Razzak Senior Counselwith Mr. Mizanul Islam, Mr. Monjur Ahmed Ansari, Mr. Kafil Uddin Chowdhury, Mr. Tajul Islam, Mr. Tanvir Ahmed Al-Amin, Mr. Imran Siddique, Mr. Abu B^k^r Siddique (Under section 20(l) of the Act XIX of 1973) I. Introduction:- 1. It is a remarkable occasion that after crcation of this Tdbunal-1, today it is gorng to deliver the first judgment of the fitst case after completion of its trial. This Tdbunal was established under the Intemational Crimes (ftibunals) Acq enacte d, n 1973 ftrereinafter referred to as the Act) by Bangladesh parliament to provide for the detention, prosecution and punishment of persons for genocide, cdmes against Humaflity, war Crimes and other Crimes under International law committed in the territory of Bangladesh dudng the rJTar of Liberation particularly between 25th March to 16 th December 1971. t 2. -

Investigative Journalism in Bangladesh: Its Growth and Role in Social Responsibility

DIU Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Volume 2 July 2014 1 INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM IN BANGLADESH: ITS GROWTH AND ROLE IN SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Md. Golam Rahman Abstract: More than four decades of Journalism practice in Bangladesh has documented enormous number of investigative reports and last three decades have seen several competitions and prizes which encouraged investigative reporting in the country. Research question of how investigative journalism is contributing to the democratic process along with other aspects of development has been explored. The social responsibility by doing investigative reporting has also been investigated. Extensive literature survey has been conducted to gauge and analyze critically the historical as well as contemporary situation of investigative journalism in the country. The study conducted an opinion survey among the journalists to understand their present perception on investigative journalism as well as the practice in the profession exposing corruption and other anomalies. Review of recent studies and research so far conducted on investigative journalism has shown a potential contribution to strengthen democratic process and social responsibility aspect of the press. How investigative reporting may contribute to combat social injustice and establish rule of law in the country has been studied. Exposing corruption in local and national levels, irregularities and unlawful activities and corruption in service providing sectors, both government and nongovernment organizations–have been found