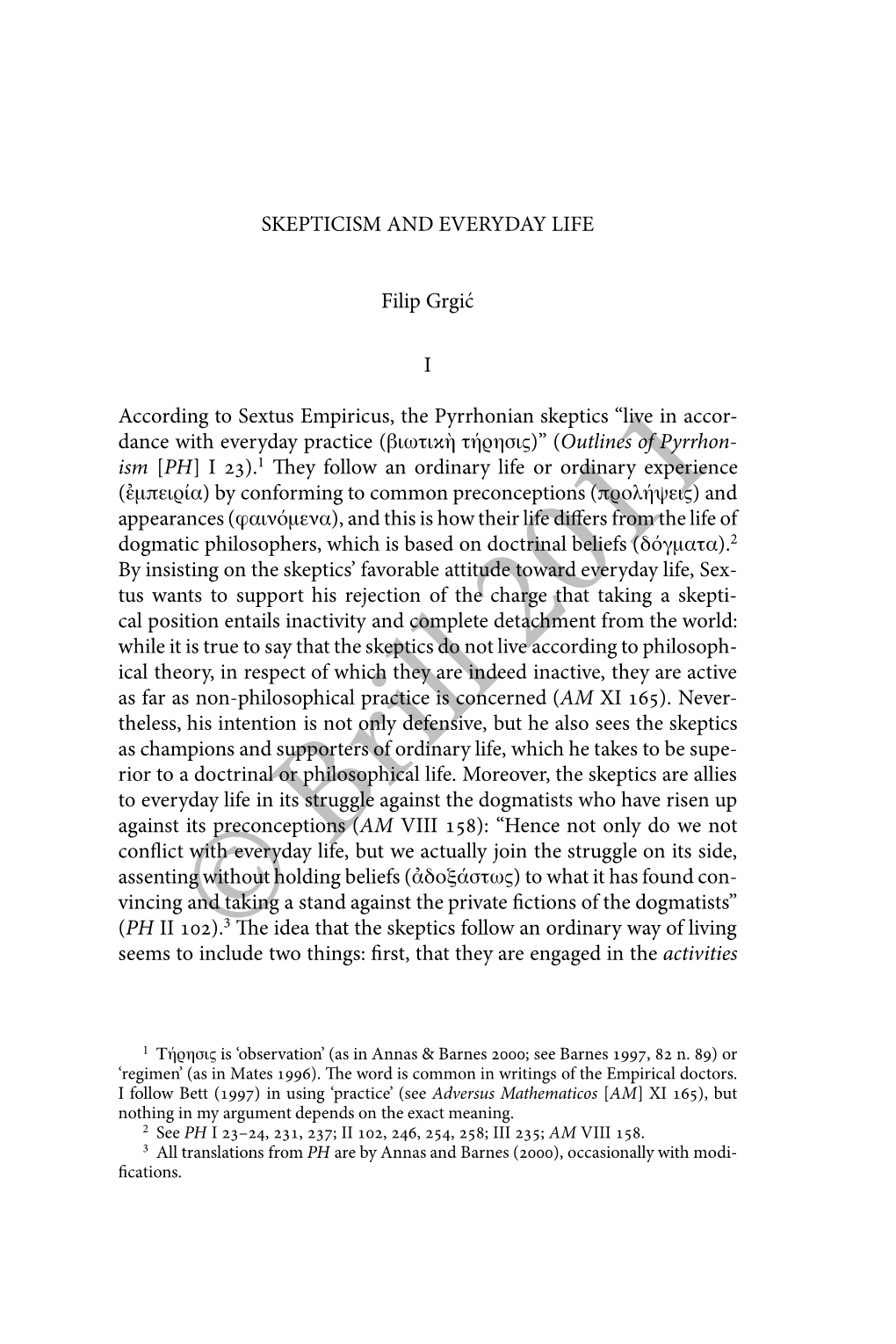

SKEPTICISM and EVERYDAY LIFE Filip Grgic I According to Sextus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM Western Pre-Socratics Fanon Heraclitus- Greek 535-475 Bayle Panta rhei Marshall Mcluhan • "Everything flows" Roman Jakobson • "No man ever steps in the same river twice" Saussure • Doctrine of flux Butler Logos Harris • "Reason" or "Argument" • "All entities come to be in accordance with the Logos" Dike eris • "Strife is justice" • Oppositional process of dissolving and generating known as strife "The Obscure" and "The Weeping Philosopher" "The path up and down are one and the same" • Theory about unity of opposites • Bow and lyre Native of Ephesus "Follow the common" "Character is fate" "Lighting steers the universe" Neitzshce said he was "eternally right" for "declaring that Being was an empty illusion" and embracing "becoming" Subject of Heideggar and Eugen Fink's lecture Fire was the origin of everything Influenced the Stoics Protagoras- Greek 490-420 BCE Most influential of the Sophists • Derided by Plato and Socrates for being mere rhetoricians "Man is the measure of all things" • Found many things to be unknowable • What is true for one person is not for another Could "make the worse case better" • Focused on persuasiveness of an argument Names a Socratic dialogue about whether virtue can be taught Pythagoras of Samos- Greek 570-495 BCE Metempsychosis • "Transmigration of souls" • Every soul is immortal and upon death enters a new body Pythagorean Theorem Pythagorean Tuning • System of musical tuning where frequency rations are on intervals based on ration 3:2 • "Pure" perfect fifth • Inspired -

On Certainty (Uber Gewissheit) Ed

Ludwig Wittgenstein On Certainty (Uber Gewissheit) ed. G.E.M.Anscombe and G.H.von Wright Translated by Denis Paul and G.E.M.Anscombe Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1969-1975 Preface What we publish here belongs to the last year and a half of Wittgenstein's life. In the middle of 1949 he visited the United States at the invitation of Norman Malcolm, staying at Malcolm's house in Ithaca. Malcolm acted as a goad to his interest in Moore's 'defence of common sense', that is to say his claim to know a number of propositions for sure, such as "Here is one hand, and here is another", and "The earth existed for a long time before my birth", and "I have never been far from the earth's surface". The first of these comes in Moore's 'Proof of the External World'. The two others are in his 'Defence of Common Sense'; Wittgenstein had long been interested in these and had said to Moore that this was his best article. Moore had agreed. This book contains the whole of what Wittgenstein wrote on this topic from that time until his death. It is all first-draft material, which he did not live to excerpt and polish. The material falls into four parts; we have shown the divisions at #65, #192, #299. What we believe to be the first part was written on twenty loose sheets of lined foolscap, undated. These Wittgenstein left in his room in G.E.M.Anscombe's house in Oxford, where he lived (apart from a visit to Norway in the autumn) from April 1950 to February 1951. -

Contextualist Responses to Skepticism

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Theses Department of Philosophy 6-27-2007 Contextualist Responses to Skepticism Luanne Gutherie Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Gutherie, Luanne, "Contextualist Responses to Skepticism." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_theses/22 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTEXTUALIST RESPONSES TO SKEPTICISM by LUANNE GUTHERIE Under the Direction of Stephen Jacobson ABSTRACT External world skeptics argue that we have no knowledge of the external world. Contextualist theories of knowledge attempt to address the skeptical problem by maintaining that arguments for skepticism are effective only in certain contexts in which the standards for knowledge are so high that we cannot reach them. In ordinary contexts, however, the standards for knowledge fall back down to reachable levels and we again are able to have knowledge of the external world. In order to address the objection that contextualists confuse the standards for knowledge with the standards for warranted assertion, Keith DeRose appeals to the knowledge account of warranted assertion to argue that if one is warranted in asserting p, one also knows p. A skeptic, however, can maintain a context-invariant view of the knowledge account of assertion, in which case such an account would not provide my help to contextualism. -

Reason and Responsibility: Readings in Some Basic Problems Of

Readings in Some Basic Problems of Philosophy JOEL FEINBERG Late of University of Arizona RUSS SHAFER-LANDAU University of Wisconsin JOEL FEINBERG (1926-2004): IN MEMORIAM vii PREFACE viii PART ONE Reason and Religious Belief 1 THE EXISTENCE AND NATURE OF GOD 6 ANSELM OF CANTERBURY: The Ontological Argument, from Proslogion 6 GAUNILO OF MARMOUTIERS: On Behalf of the Fool 7 WILLIAM L. ROWE: The Ontological Argument 11 SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS: The Five Ways, from Summa Theologica 21 SAMUEL CLARKE: A Modern Formulation of the Cosmological Argument 22 WILLIAM L. ROWE: The Cosmological Argument 23 WILLIAM PALEY: The Argument from Design 32 DAVID HUME: Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion 38 THE PROBLEM OF EVIL 72 FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY: Rebellion 72 J. L. MACKIE: Evil and Omnipotence 78 GEORGE SCHLESINGER: The Problem of Evil and the Problem of Suffering 86 RICHARD SWINBURNE: Why God Allows Evil 89 B. C. JOHNSON: God and the Problem of Evil 97 REASON AND FAITH 101 W. K. CLIFFORD: The Ethics of Belief 101 WILLIAM JAMES: The Will to Believe 106 KELLY JAMES CLARK: Without Evidence or Argument 114 BLAISE PASCAL: The Wager 119 SIMON BLACKBURN: Miracles and Testimony 122 PART TWO Human Knowledge: Its Grounds and Limits 129 SKEPTICISM 137 JOHN POLLOCK: A Brain in a Vat 137 PETER UNGER: An Argument for Skepticism 139 RODERICK M. CHISHOLM: The Problem of the Criterion 150 OUR KNOWLEDGE OF THE EXTERNAL WORLD 157 BERTRAND RUSSELL: Appearance and Reality and the Existence of Matter RENE DESCARTES: Meditations on First Philosophy 164 JOHN LOCKE: The Causal Theory of Perception 197 GEORGE BERKELEY: Of the Principles of Human Knowledge 205 THOMAS REID: Of the Existence of a Material World 213 G. -

Contextualism in Context: Interview with Michael Williams

AVANT , Vol. XI, No. 2 ISSN: 2082-6710 avant.edu.pl/en DOI: 10.26913/avant.2020.02.03 Contextualism in Context: Interview with Michael Williams Luca Corti University of Porto MLAG – Mind, Language, and Action Group (Institute of Philosophy, U.Porto) luca.corti @ hotmail.de Diana Couto University of Barcelona BIAP/LOGOS Research Group in Analytic Philosophy MLAG – Mind, Language, and Action Group (Institute of Philosophy, U.Porto) dpcouto @ ub.edu Received 4 October 2019; accepted 5 October 2019; published 10 January 2020 "Contextualism" is usually taken as the name for a very general view that can be found in different areas: from semantics to epistemology, from philosophy of language to philosophy of action. According to contextualism the role of context is necessary for an utterance, knowledge claim or action to have meaning or be intelligible. In philosophy of language, the idea is that what an utterance expresses depends on the context, which therefore has a role in determining its truth-conditions. One of the most renowned “radical contextualists”, Charles Travis writes: “words may have any of many semantics, compatibly with what they mean. Words in fact vary their semantics from one speaking of them to another” (2008, p. 123). Epistemic contextualism, on the other hand, is the view that certain features of the context affect the standards that a subject S must meet in order for S' beliefs to count as knowledge (or, alternatively, for a sentence attributing knowledge to S to be true). Knowledge attributions are context-sensitive. Like the other forms of contextualism, epistemic contextualism comes in various flavors. -

Wittgenstein's Refutation of Idealism

1 Wittgenstein’s Refutation of Idealism Wittgenstein’s notes, collected as “On Certainty”, are a gold mine of ideas for philosophers concerned with knowledge and scepticism.1 But in my view, Wittgenstein’s approach to scepticism is still not well understood. Obviously, a short essay is no place for an exhaustive treatment of Wittgenstein’s anti-sceptical ideas. Instead, I shall present a reconstruction of a particular argument that I call “Wittgenstein’s Refutation of Idealism”. This argument is developed in the first sixty-five sections of “On Certainty”, although there is a later passage (90) that must also be considered. To appreciate this argument, it is essential to be clear about its target. It is evident that Wittgenstein’s thoughts on scepticism are prompted by Moore’s “Proof of an External World” and “Defence of Common Sense”. 2 But these well-known papers differ in an important way. In his “Proof”, Moore’s topic is external world scepticism in its most general form: his aim is to prove, in defiance of the sceptic and idealist, that external objects, defined as “things to be met with in space”, really do exist. By contrast, in his “Defence”, Moore undertakes to defend a body of rather more specific beliefs: that the earth has existed for many years past, that he has never been far from its surface, and 1 Ludwig Wittgenstein, On Certainty, edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, translated by Denis Paul and G.E.M. Anscombe (New York: J. and J. Harper 1969). References to this work are given in the text by numbered, displayed paragraphs or by parenthetical paragraph numbers. -

Cursory Notes on Vimsatika

!1 Cursory Notes on Viṃśatikā Vijñaptimātratāsiddhiḥ. Kaspars Eihmanis PhD student, National Chengchi University, Faculty of Philosophy Viṃśatikā Vijñaptimātratāsiddhiḥ opens with the statement of the author’s thesis, stated in the auto-commentary vṛtti : 「安⽴⼤乘三界唯識。以契經說三界唯⼼。」1 According to the Mah"y"na the three realms of sensuous desire, form and formlessness are consciousness only (vijñapti-mātratā; 唯識). This statement embraces the view that everything we come to know, become aware of, i.e. cognise, is dependent on transformations of consciousness. This statement is further attested by the affirmation found in Mah"y"na scriptures that the three worlds are mind-only (cittam"tra; 唯⼼). Vasubadhu also provides us with the definition of the key terms found throughout the text, concepts forming the core of the Yog"c"ra theory of consciousness and epistemology: 「⼼意識了名之差別。此中說⼼意兼⼼所。」2 Mind (citta; ⼼), thought (manas; 意 ), consciousness (vijñāna; 識) and cognising (vijñapti; 了) are different names, hence throughout the treatise the concepts of mind and thought are used together with the concept of mental concomitants (caitta; ⼼所) . Preliminary statement describes not only the thesis of the author, but also recounts the intention of the author in writing the treatise, those countering the possible counter-arguments against vijñapti-mātratā. This becomes obvious upon reading the following verses and their commentaries, the rest of the treatise is devoted to providing proofs for the vijñapti-mātratā thesis as well as refuting counter-arguments raised by Buddhist and non-Buddhist critics, who mainly hail form the realist schools of Indian philosophy. As a modern reader, I might employ two different approaches in an attempt to make the text philosophically relevant. -

The Self-Fashioning of Emil Du Bois-Reymond

Science in Context (2020), 33,19–35 doi:10.1017/S0269889720000101 RESEARCH ARTICLE Physiology and philhellenism in the late nineteenth century: The self-fashioning of Emil du Bois-Reymond Lea Beiermann* and Elisabeth Wesseling Maastricht University *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Argument Nineteenth-century Prussia was deeply entrenched in philhellenism, which affected the ideological frame- work of its public institutions. At Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University, philhellenism provided the ratio- nale for a persistent elevation of the humanities over the burgeoning experimental life sciences. Despite this outspoken hierarchy, professor of physiology Emil du Bois-Reymond eventually managed to increase the prestige of his discipline considerably. We argue that du Bois-Reymond’s use of philhellenic repertoires in his expositions on physiology for the educated German public contributed to the rise of physiology as a renowned scientific discipline. Du Bois-Reymond’s rhetorical strategies helped to disassociate experimen- tal physiology from clinical medicine, legitimize experimental practices, and associate the emerging disci- pline with the more esteemed humanities and theoretical sciences. His appropriation of philhellenic rhetoric thus spurred the late nineteenth-century change in disciplinary hierarchies and helped to pave the way for the current hegemonic position of the life sciences. Keywords: physiology; Du Bois-Reymond; discipline formation; interdisciplinarity; university history; life sciences; rhetoric; scientific self-fashioning German physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond has been described as “the most important forgotten intellectual of the nineteenth century” (Finkelstein 2013, xv). Born in 1818, he became a much- acclaimed physiologist, nationally and internationally. He was especially well known for his eloquent speeches on science and culture. -

Epistemology.Pdf

Epistemology An overview Contents 1 Main article 1 1.1 Epistemology ............................................. 1 1.1.1 Background and meaning ................................... 1 1.1.2 Knowledge .......................................... 1 1.1.3 Acquiring knowledge ..................................... 5 1.1.4 Skepticism .......................................... 7 1.1.5 See also ............................................ 7 1.1.6 References .......................................... 8 1.1.7 Works cited .......................................... 9 1.1.8 External links ......................................... 10 2 Knowledge 11 2.1 Knowledge ............................................... 11 2.1.1 Theories of knowledge .................................... 11 2.1.2 Communicating knowledge ................................. 12 2.1.3 Situated knowledge ...................................... 13 2.1.4 Partial knowledge ...................................... 13 2.1.5 Scientific knowledge ..................................... 13 2.1.6 Religious meaning of knowledge ............................... 14 2.1.7 See also ............................................ 15 2.1.8 References .......................................... 15 2.1.9 External links ......................................... 16 2.2 Belief ................................................. 16 2.2.1 Knowledge and epistemology ................................. 17 2.2.2 As a psychological phenomenon ............................... 17 2.2.3 Epistemological belief compared to religious belief -

Was Moore a Moorean? on Moore and Scepticism

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 6-1-2009 Was Moore A Moorean? On Moore And Scepticism Peter Baumann Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Peter Baumann. (2009). "Was Moore A Moorean? On Moore And Scepticism". European Journal Of Philosophy. Volume 17, Issue 2. 181-200. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0378.2008.00300.x https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/21 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Was Moore a Moorean? On Moore and Scepticism1 Peter Baumann Abstract One of the most important views in the recent discussion of epistemological scepticism is Neo- Mooreanism. It turns a well-known kind of sceptical argument (the dreaming argument and its different versions) on its head by starting with ordinary knowledge claims and concluding that we know that we are not in a sceptical scenario. This paper argues that George Edward Moore was not a Moorean in this sense. Moore replied to other forms of scepticism than those mostly discussed nowadays. His own anti-sceptical position turns out to be very subtle and complex; furthermore it changed over time. This paper follows Moore's views of what the sceptical problem is and how one should respond to it through a series of crucial papers with the main focus being on Moore's 'Proof of an External World'. -

Gregory W. Dawes, Galileo and the Conflict Between Religion and Science

Galileo and the Conflict Between Religion and Science Gregory W. Dawes Prepublication version; published in the Philosophy of Religion Series by Routledge (New York) in 2016. The definitive version is the version published by Routledge; you should cite the published version when reviewing or commenting on the work. This draft is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License. You are free to cite this material provided you attribute it to its author; you may also make copies, but you must include the author’s name and a copy of this notice. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ To Kitty This is a small episode in an unending argument between those who know they are right and therefore claim the mandate of heaven, and those who suspect that the human race has nothing but the poor candle of reason by which to light its way. Christopher Hitchens iii Contents List of Figures....................................................................................................8 Introduction...............................................................................................1 1. The Old Conflict Thesis.................................................................................3 1.1 John William Draper..............................................................................3 1.2 Andrew Dickson White...........................................................................7 1.3 Rejection of the Draper-White Thesis.................................................10 2. The Relation of Religion -

The Paradox of Moore's Proof of an External World

The Philosophical Quarterly doi: ./j.-...x THE PARADOX OF MOORE’S PROOF OF AN EXTERNAL WORLD B A C Moore’s proof of an external world is a piece of reasoning whose premises, in context, are true and warranted and whose conclusion is perfectly acceptable, and yet immediately seems flawed. I argue that neither Wright’s nor Pryor’s readings of the proof can explain this paradox. Rather, one must take the proof as responding to a sceptical challenge to our right to claim to have warrant for our ordinary empirical beliefs, either for any particular empirical belief we might have, or for belief in the existence of an external world itself. I show how Wright’s and Pryor’s positions are of interest when taken in connection with Humean scepticism, but that it is only linking it with Cartesian scepticism which can explain why the proof strikes us as an obvious failure. ... I remember with particular vividness that on one such occasion I found him poring over a piece of paper on which was handwritten a very short argument entitled ‘Proof of an External World’. I read it with some dismay. ‘Moore,’ I said, ‘surely your proof is a simple petitio principii?’ ‘Indeed, it is not,’ he smilingly replied. ‘Ah, so then does it perhaps suffer a failure of warrant transmission?’ ‘No’, he said. Bewildered, I ventured, ‘Then is it merely dialectically ineffec- tive?’ ‘No’, he said, smiling more mysteriously than ever. Then it came to me. ‘Moore’, I said, ‘is your proof merely completely irrelevant to the point at issue?’ ‘Yes!’ he said, clapping his hands with delight.