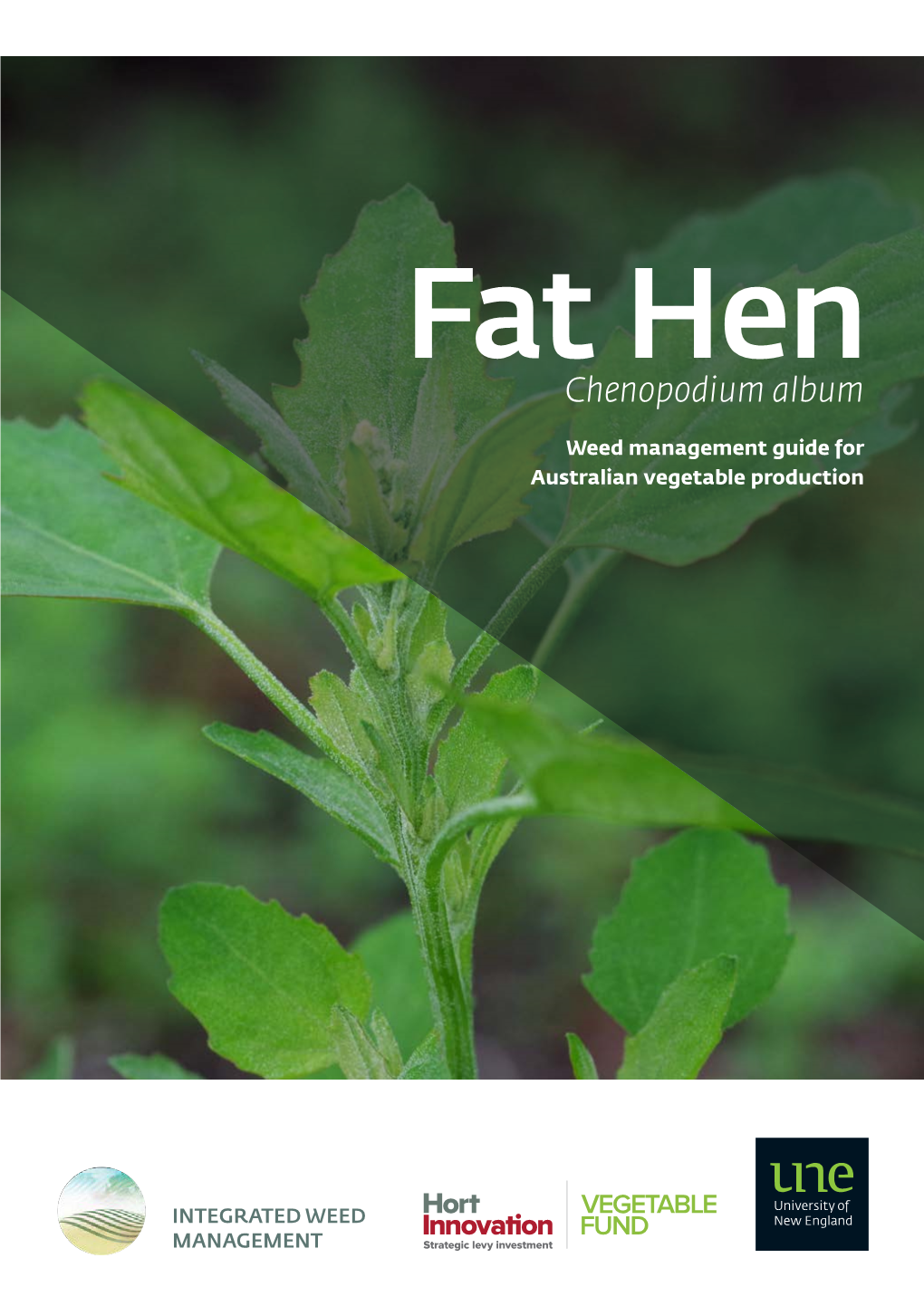

Chenopodium Album

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pest Management of Small Grains—Weeds

PUBLICATION 8172 SMALL GRAIN PRODUCTION MANUAL PART 9 Pest Management of Small Grains—Weeds MICK CANEVARI, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, San Joaquin County; STEVE ORLOFF, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Siskiyou County; RoN VARGAS, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, UNIVERSITY OF Madera County; STEVE WRIGHT, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm CALIFORNIA Advisor, Tulare County; RoB WILsoN, University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Division of Agriculture Advisor, Lassen County; DAVE CUDNEY, Extension Weed Scientist Emeritus, Botany and and Natural Resources Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside; and LEE JACKsoN, Extension Specialist, http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu Small Grains, Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis This publication, Pest Management of Small Grains—Weeds, is the ninth in a fourteen- part series of University of California Cooperative Extension online publications that comprise the Small Grain Production Manual. The other parts cover specific aspects of small grain production practices in California: • Part 1: Importance of Small Grain Crops in California Agriculture, Publication 8164 • Part 2: Growth and Development, Publication 8165 • Part 3: Seedbed Preparation, Sowing, and Residue Management, Publication 8166 • Part 4: Fertilization, Publication 8167 • Part 5: Irrigation and Water Relations, Publication 8168 • Part 6: Pest Management—Diseases, Publication 8169 • Part 7: -

IN14 Haute Healthy Cuisine Recipes 02.Indd

Haute healthy cuisine BEETROOT WITH MUSTARD SORBET, 01 / L’ATELIER DE JOËL ROBUCHON SILVERY SEA BASS IN HAY-STEAM DRIZZLED WITH BRAISING JUICE AND HERBS BY MICHEL GUÉRARD, LES PRÉS D’EUGÉNIE / 02 CABBAGE AND BEETS WITH PEAR 03 / BY PAUL IVIC, TIAN RESTAURANT WATER GARDEN BY HEINZ BECK, LA PERGOLA / 04 XAVIER BOYER Beetroot with mustard sorbet, L’Atelier de Joël / 01 Robuchon METHOD GREEN MUSTARD SORBET Bring the water and the sugar to boil to make a syrup. Once it has reached a syrup-like consistency, take it off the heat and mix with the green mustard. Slowly add the orange juice and mix together. Freeze the mixture and then place in a home ice cream machine or Pacojet. BEETROOT TARTARE Take a ripe avocado and blend into a paste. Dice the cooked beetroot into small cubes along with the Granny Smith and Golden apples. In a separate bowl, incorporate the blended avocado with the diced beetroot and apples to create an equal mixture of ingredients. Plate in a circle on the plate and finish with a herb salad and drizzle the extra virgin olive oil on top of the tartare. I like to use INGRED IENTS tarragon, basil, dill and chives for a delicate, pretty yet punchy salad. GREEN MUSTARD SORBET • 200ml orange juice • 200ml water • 60g sugar • 200g green mustard BEETROOT TARTARE • 100g cooked beetroot • 75g avocado • 50g Granny Smith apple • 50g golden apple • 20ml extra virgin olive oil Haute healthy cuisine FOUR International 01/16 MICHEL GUÉRARD Silvery sea bass in hay-steam / drizzled with 02 braising juice and herbs METHOD BROTH SAUCE Bring the vegetable broth to boil with butter, garlic crisps and teriyaki sauce. -

An Overview of Nutritional and Anti Nutritional Factors in Green Leafy Vegetables

Horticulture International Journal Review Article Open Access An overview of nutritional and anti nutritional factors in green leafy vegetables Abstract Volume 1 Issue 2 - 2017 Vegetables play important role in food and nutritional security. Particularly, green leafy Hemmige Natesh N, Abbey L, Asiedu SK vegetables are considered as exceptional source for vitamins, minerals and phenolic Department of Plant, Food, and Environmental Sciences, compounds. Mineral nutrients like iron and calcium are high in leafy vegetables than Dalhousie University, Canada staple food grains. Also, leafy vegetables are the only natural sources of folic acid, which are considerably high in leaves of Moringa oleifera plants as compared to other Correspondence: Hemmige Natesh N, Faculty of Agriculture, leafy and non-leafy vegetables. This paper reviewed nutritional and anti nutritional Department of Plant, Food, and Environmental Sciences, factors in some important common green leafy vegetables. The type and composition Dalhousie University, PO Box 550, Truro B2N 5E3, Nova Scotia, of nutritional and anti nutritional factors vary among genera and species of different Canada, Email [email protected] edible leafy vegetables plants. Anti nutritional factors are chemical compounds in plant tissues, which deter the absorption of nutrients in humans. Their effects can Received: October 06, 2017 | Published: November 17, 2017 be direct or indirect and ranges from minor reaction to death. Major anti nutritional factors such as nitrates, phytates, tannins, oxalates and cyanogenic glycosides have been implicated in various health-related issues. Different processing methods such as cooking and blanching can reduce the contents of anti-nutritional factors. This paper also discussed in brief the various analytical methods for the determination of the various nutritional and anti-nutritional factors in some green leafy vegetables. -

Quantification of Airborne Peronospora for Downy Mildew Disease Warning

Quantification of airborne Peronospora for downy mildew disease warning Steve Klosterman Salinas, CA The Salinas Valley, California ~ 70 % US fresh market spinach grown in CA ~ 50 % of that production in the Salinas Valley ~ 13 km Downy mildew on spinach Peronospora effusa (Peronospora farinosa f. sp. spinaciae) 50 μm Symptoms: Chlorotic Signs: typically grey-brownish spots on top of leaves. downy masses of spores on the underside of leaf Downy mildew on spinach Peronospora effusa Objectives: 1. Develop an assay (qPCR) for detection and quantification of DNA from airborne Peronospora effusa. 2. Validate the assay in the field. 3. Assess levels of Peronospora effusa DNA associated with disease development in a field plot. Peronospora effusa/spinach Peronospora schachtii/chard 50 μm TaqMan assay to distinguish Peronospora effusa from related species (18S rRNA gene target) Klosterman et al. 2014. Phytopathology 104 :1349-1359. Test of a TaqMan assay to distinguish Peronospora effusa from related species on various plant hosts Downy mildew infected host plant qPCR detection Spinacia oleracea (spinach) + Beta vulgaris (beet/Swiss chard) +/- Chenopodium album (lambsquarters) - Atriplex patula (spear saltbush) - Spergula arvensis (corn spurry) - Bassia scoparia (burningbush) - Chenopodium polyspermum (manyseed goosefoot) - Chenopodium bonus-henricus (good King Henry) - Rumex acetosa (garden sorrel) - Dysphania ambrosiodes (epazote) - DNA template integrity tested by SYBR green assays prior to specificity tests. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-specific PCRs for determining frequencies of target alleles ∆Cq Freq. SNP1= 1/(2 + 1) where ∆Cq = (Cq of SNP1–specific PCR) – (Cq of SNP2–specific PCR) Klosterman et al. 2014. Phytopathology. 104 :1349-1359. Adapted from Germer et al. 2000. Genome Research 10:258–266. -

Reduced-Rate Herbicide Sequences in Beetroot Production

Eleventh Australian Weeds Conference Proceedings REDUCED-RATE HERBICIDE SEQUENCES IN BEETROOT PRODUCTION C.W.L. Henderson Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Gatton Research Station, PO Box 241, Gatton, Queensland 4343, Australia Summary Weed management in beetroot is costly; cur- efficacy and phytotoxicity of low rates of post-emergence rent herbicide strategies are expensive, do not provide herbicides in beetroot production. reliable control and occasionally cause significant crop damage. Sugarbeet producers in the USA and Europe MATERIALS AND METHODS sequentially apply beet herbicides at low rates, with less I conducted the experiment, comprising five replicates of risk of crop damage and at reduced costs. nine weed management treatments, on a black earth soil In a 1995 experiment at Gatton Research Station, at the QDPI Gatton Research Station in south-east we sprayed 4-true-leaf beetroot with a mixture of Queensland. Beetroots (cv. Early Wonder Tall Top) were 0.78 kg ha-1 of phenmedipham and 1.00 kg ha-1 of sown on 30 March 1995, in rows 0.75 m apart, with ethofumesate as the current commercial recommenda- intra-row spacings of 0.05 m. Apart from weed treat- tion. Compared to a hand-weeded control, this reduced ments, beetroot were grown using standard agronomy. beetroot yields by 25%. Spraying 0.31-0.39 kg ha-1 of phenmedipham when beetroots had cotyledons and Weed management treatments I used the registered 2-true-leaves, followed by another 0.31 kg ha-1 one week beet herbicides phenmedipham (Betanal®) and etho- later, yielded 87% of the hand-weeded beetroots. The fumesate (Tramat®) in this experiment. -

Understanding the Weedy Chenopodium Complex in the North Central States

UNDERSTANDING THE WEEDY CHENOPODIUM COMPLEX IN THE NORTH CENTRAL STATES BY SUKHVINDER SINGH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop Sciences in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Patrick J. Tranel, Chair Associate Professor Aaron G. Hager Associate Professor Geoffrey A. Levin Assistant Professor Matthew E. Hudson ABSTRACT The genus Chenopodium consists of several important weed species, including Chenopodium album, C. berlandieri, C. strictum, and C. ficifolium. All of these species share similar vegetative morphology and high phenotypic plasticity, which makes it difficult to correctly identify these species. All of these weedy Chenopodium species have developed resistance to one or more classes of herbicides. An experiment was conducted to determine if there is variability in response of Chenopodium species present in the North Central states to glyphosate. Our results indicate variable responses within and among the Chenopodium species. Species such as C. berlandieri and C. ficifolium had higher levels of tolerance to glyphosate than did various accessions of C. album. In another experiment, 33 populations of Chenopodium sampled across six North Central states were screened with glyphosate. The results showed variable responses to glyphosate within and among the Chenopodium populations. In general, the Chenopodium populations from Iowa were more tolerant, but some biotypes from North Dakota, Indiana and Kansas also had significantly high tolerance to glyphosate. Given there are species other than C. album that have high tolerance to glyphosate, and there are Chenopodium populations across the North Central states that showed tolerance to glyphosate, one intriguing question was to whether the Chenopodium populations were either biotypes of C. -

Beta Vulgaris As a Natural Nitrate Source for Meat Products: a Review

foods Review Beta vulgaris as a Natural Nitrate Source for Meat Products: A Review Paulo E. S. Munekata 1,*, Mirian Pateiro 1 , Rubén Domínguez 1 , Marise A. R. Pollonio 2,Néstor Sepúlveda 3 , Silvina Cecilia Andres 4, Jorge Reyes 5, Eva María Santos 6 and José M. Lorenzo 1,7 1 Centro Tecnológico de la Carne de Galicia, Rúa Galicia No. 4, Parque Tecnológico de Galicia, San Cibrao das Viñas, 32900 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (R.D.); [email protected] (J.M.L.) 2 Department of Food Technology, School of Food Engineering, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas 13083-862, SP, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Producción Agropecuaria, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales, Universidad de La Frontera, Campus Integrado Andrés Bello Montevideo s/n, Temuco 4813067, Chile; [email protected] 4 Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo en Criotecnología de Alimentos (CIDCA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnicas (CONICET), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, CIC-PBA, 47 y 116, La Plata 1900, Argentina; [email protected] 5 Departamento de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Alimentos, Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Calle París, San Cayetano Alto, Loja 110107, Ecuador; [email protected] 6 Area Academica de Quimica, Universidad Autonoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Carr. Pachuca-Tulancingo Km. 4.5, Mineral de la Reforma, Hidalgo 42184, Mexico; [email protected] 7 Área de Tecnología de los Alimentos, Facultad de Ciencias de Ourense, Universidad de Vigo, 32004 Ourense, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Munekata, P.E.S.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Pollonio, M.A.R.; Abstract: Curing meat products is an ancient strategy to preserve muscle foods for long periods. -

15IFM07 Cardiometabolic Food Plan 1200-1400 Final V4.Indd

Cardiometabolic Food Plan (1200–1400 Calories) PROTEINS Proteins o Hummus or other o Refined beans, FATS & OILS Fats bean dips–⅓ c vegetarian–¼ c Servings/day: 7–9 o o o o o o o 1 serving = 110 calories, 15 g carbs, 7 g protein Servings/day: 3–4 o o o o o o o Lean, free-range, grass-fed, organically grown Minimally refined, cold-pressed, organic, meats; non-GMO plant proteins and wild-caught DAIRY & ALTERNATIVES Proteins/Carbs non-GMO preferred fish preferred o Avocado–2 T o Olives, black or Servings/day: 1 o o o o o o o Animal Proteins: o Meat: Beef, buffalo, o Butter–1 t, 2 t green–8 elk, lamb, venison, o Cheese, low-fat–1 oz Unsweetened whipped o Oils, cooking: other wild game–1 oz o Cheese, hard–½ oz o Buttermilk–4 oz o Yogurt, plain or o Chocolate, dark, Butter, coconut o Poultry (skinless): (virgin), grapeseed, o Cottage cheese, Kefir, plain–4 oz coconut (cultured 70% or higher Chicken, Cornish o low-fat–¼ c coconut milk)–6 oz cocoa–1 sq, olive, (extra virgin) hen, turkey–1 oz o Milk: Cow, goat–4 oz rice bran, sesame–1 t o Yogurt, Greek, 1 square = 7 g o Egg or 2 egg o Milk: Almond, Plant Protein: plain–4 oz o Oils, salad: Almond, whites–1 coconut, flaxseed, o Coconut milk, o Burger alternatives: avocado, canola, o Egg substitute–⅔ c hazelnut, hemp, oat, regular, canned– Bean, mushroom, 1½ T flaxseed, grapeseed, o Feta cheese, soy–8 oz hempseed, high-oleic soy, veggie–1 oz o Coconut milk, light, low-fat–1 oz 1 serving = 50-100 calories, 12g carbs, 7g protein safflower,olive (extra o Miso–3 T canned–3 T o Parmesan cheese–2 T Low -

Original Research Article Assessment of the Nutritional Value of Selected

Original Research Article Assessment of the Nutritional Value of Selected Wild Leafy Vegetables Growing in the Roma Valley, Lesotho . ABSTRACT Keywords: wild leafy, Amaranthus, micronutrients, vegetables, carbohydrates, macronutrients Objective: The aim of this study was to determine the nutrient content of nine selected wild leafy vegetables growing in Roma Valley of Lesotho as a means to achieve food security, improve nutritional and dietary diversity and address malnutrition in rural communities Methodology: The fresh vegetables were analysed for proximate composition, and Ca, Mg, Na, P, K, Fe, Mn, Se, Cu and Zn and vitamin C. Analyses were carried out using standard methods. Results: The proximate analysis revealed a high in moisture (81.15 - 92.23%), some were high in protein, vitamin C, Cu, Mn, K and Fe. Chenopodium album has the highest protein (31.53±8.65 mg/100g fresh weight (FW); and Rorripa nudiscula (51.4% of RDA). Chenopodium album and Rorripa nudiscula were rich in Ca, 1598.21±15.25 mg/100g FW and 1508.50±25.40 mg/100g FW and in Mg, 505.14±35.55 mg/100g FW and 525.18 mg/100g FW respectively. The vegetables were rich in K, but low in Na, with Na-to-K ratio < 1.0, indicating that the vegetables could be ideal source of balanced sodium and potassium intake in diet. The vegetables were rich in Cu with ranging from 114.4% of RDA in Hypochaeris radicata to 342.2% of RDA in Chenopodium album. Fe was abundant in Rorripa nudiscula 251.7% of RDA and Chenopodium album 187.8% of the RDA. -

Biology and Management of Common Lambsquarters

GWC-11 The Glyphosate, Weeds, and Crops Series Biology and Management of Common Lambsquarters Bill Curran, The Pennsylvania State University Christy Sprague, Michigan State University Jeff Stachler, The Ohio State University Mark Loux, The Ohio State University Purdue Extension 1-888-EXT-INFO Glyphosate, Weeds, and Crops TheThe Glyphosate,Glyphosate, Weeds,Weeds, andand CropsCrops SeriesSeries This publication was reviewed and endorsed by the Glyphosate, Weeds, and Crops Group. Members are university weed scientists from major corn and soybean producing states who have been working on weed management in glyphosate-resistant cropping systems. To see other titles in the Glyphosate, Weeds, and Crops series, please visit the Purdue Extension Education Store: www.ces.purdue.edu/new. Other publications in this series and additional information and resources are available on the Glyphosate, Weeds, and Crops Group Web site: www.glyphosateweedscrops.org. University of Delaware University of Nebraska Mark VanGessel Mark Bernards University of Guelph Stevan Knezevic Peter Sikkema Alex Martin University of Illinois North Dakota State University Aaron Hager Richard Zollinger Dawn Nordby The Ohio State University Iowa State University Mark Loux Bob Hartzler Jeff Stachler Mike Owen The Pennsylvania State University Kansas State University Bill Curran Dallas Peterson Purdue University Michigan State University Thomas Bauman Jim Kells Bill Johnson Christy Sprague Glenn Nice University of Minnesota Steve Weller Jeff Gunsolus South Dakota State University University of Missouri Mike Moechnig Kevin Bradley Southern Illinois University Reid Smeda Bryan Young University of Wisconsin Chris Boerboom Financial support for developing, printing, and distributing this publication was provided by BASF, Bayer Crop Science, Dow AgroSciences, Dupont, Illinois Soybean Association, Indiana Soybean Alliance, Monsanto, Syngenta, Valent USA, and USDA North Central IPM Competitive Grants Program. -

Beetroot (Silver Beet) Leaf Spot (320)

Pacific Pests and Pathogens - Fact Sheets https://apps.lucidcentral.org/ppp/ Beetroot (silver beet) leaf spot (320) Photo 1. Leaf spot on beetroot, Cercospora beticola. Common Name Beetroot leaf spot Scientific Name Cercospora beticola Distribution Worldwide. Asia, Africa, North, South and Central America, the Caribbean, Europe, Oceania. It is recorded from Australia, Cook Islands, New Caledonia, Niue, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga. Hosts Beta species (Beta vulgaris, beetroot, silver beet, and Beta vulgaris variety saccharifera, sugar beet), Amaranthus, spinach, and lettuce. Many weeds are hosts: Chenopdium, Amaranthus, Plantago and Verbena. Symptoms & Life Cycle Leaf spots, round to irregular, 2-5 mm wide, ash-grey to pale brown, usually with a brown or reddish-purple border often severe on older leaves (Photo 1). Spores develop in the centre of the spots. The centre of the spots fall out, giving a 'shot-hole' symptom. The disease can be severe on older leaves; the spots join together, the leaves dry and later collapse, although remain attached to the plant. Spread over short distances occur by rain splash whereas, over longer distances, it occurs in wind and seed. Survival occurs on crop remains: spores only last a few months, but the fungal strands of the stromata, last 1-2 years. The fungus also survives on weeds and seeds between crops of beet. Seed infection is common in sugarbeet, especially in Europe, the US and India. Warm (20-30°C) wet weather with showers favours the disease. Impact Severe outbreaks with loss of (sugar) yield are reported in sugar beet from many countries of the world. -

Beta Vulgaris: a Systematic Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by shahrekord university of medical scinces Available online a t www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Der Pharmacia Lettre, 2016, 8 (19):404-409 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html) ISSN 0975-5071 USA CODEN: DPLEB4 Chemistry and pharmacological effect of beta vulgaris: A systematic review Sepide Miraj M.D., Gynecologist, Fellowship of Infertility, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Beta vulgaris is a plant native to Mediterranean, the Atlantic coast of Europe, the Near East, and India belong to Amaranthaceae, Genus Beta, and Subfamily Betoideae. The aim of this study is to overview Chemistry and pharmacological effect of beta vulgaris . This review article was carried out by searching studies in PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, and IranMedex databases up to 201 6.Among 89 found articles, 54 articles were included. The search terms were “Beta vulgaris”, “therapeutic”, and “pharmacological”, "Chemistry ". Various studies have shown that Beta vulgaris possess anti-inflammatory effect, antioxidant Properties, anti-stress effect, anti-Anxiety and anti-depressive effect, anti-cancer, antihypertensive effect, hydrophobic properties, anti-sterility effects. The result of this study have found various constituents of Beta vulgaris exhibit a variety of therapeutic