Street Vendors in Ahmedabad: Status, Contribution and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model Code Casts Shadow on World Heritage Week Celebrations

2/7/2020 Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations Claim your 100 coins now ! Sign Up HOME PHOTOS INDIA ENTERTAINMENT SPORTS WORLD BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY LIFESTYLE Sexuality Happy Rose Valentine's Day 2020: Day 2020: From Share these Rose Day to WhatsApp Promise Day, messages, here's f... $S14M.99S, couplets wit$h10.1..9. 9 $99.99 NADA bans Indian$15.29 boxer Sumit San$gwan29.99 Propose Day 2020: Best This Valentine's Day, surprise your bae for a year for failing dope test WhatsApp messages, with 'pizza ring'; h... Diwali 2019: 5 DIY ways to use fairy lights SMS, couplets, quotes to Rose Day 2020: From Red to peach, here's for decoration this Diwali express... what colours of rose represen... TRENDING# Delhi Elections 2020 CAA protests Ind vs NZ Nirbhaya JNU Home » India » Ahmedabad Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations The civic body is taking steps on how to ensure that the week-long World Heritage Week celebration is a memorable one in wake of the Model Code of Conduct Bhadra Fort Bhadra Fort, which is a heritage site in the city The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation is all geared up to celebrate the World Heritage Week from November 19, the rst after it was declared as SHARE the rst World Heritage City of India by the UNESCO on July 8. However, AMC which had to shelve its plan to observe fortnight-long celebration beginning August 1 to showcase its achievement, in the wake WRITTEN BY of heavy rains and subsequent widespread oods across the state does n want to take any chances this time. -

Special Report on Ahmedabad City, Part XA

PRG. 32A(N) Ordy. 700 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PAR T X-A (i) SPECIAL REPORT ON AHMEDABAD CITY R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE Rs. 9.75 P. or 22 Sh. 9 d. or $ U.S. 3.51 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: * I-A(i) General Report * I-A(ii)a " * I-A(ii)b " * I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :\< I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey .\< I-C Subsidiary Tables -'" II-A General Population Tables * II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) * II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) * II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :l< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) * IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments * IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables :\< V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) ** VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat * VII-B Fairs and Festivals * VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration " ~ N ~r£br Sale - :,:. _ _/ * VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation ) :\' IX Atlas Volume X-A Special Report on Cities * X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory '" X-C Special Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS * 17 District Census Handbooks in English * 17 District Census Handbooks in Gl~arati " Published ** Village Survey Monographs for SC\-Cu villages, Pachhatardi, Magdalla, Bhirandiara, Bamanbore, Tavadia, Isanpur and Ghclllvi published ~ Monographs on Agate Industry of Cam bay, Wood-carving of Gujarat, Patara Making at Bhavnagar, Ivory work of i\1ahllva, Padlock .i\Iaking at Sarva, Seellc l\hking of S,v,,,-kundb, Perfumery at Palanpur and Crochet work of Jamnagar published - ------------------- -_-- PRINTED BY JIVANJI D. -

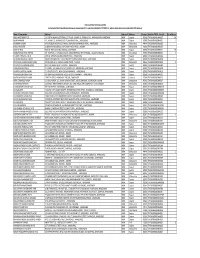

Statement of Unclaimed Dividend Amount Consecutively for 7 Years from Dividend of FY 2010-11, Whose Shares Are to Be Transferred to IEPF Account

THE ANUP ENGINEERING LIMITED Statement of Unclaimed Dividend amount consecutively for 7 years from Dividend of FY 2010-11, whose shares are to be transferred to IEPF Account Name of Shareholder Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Pincode Folio No / DP ID - Client ID No. of Shares AEGIS INVESTMENTS LTD C/O.SHETH LALBHAI DALPATBHAI, 1ST FLOOR, 'AKSHAY' 53, SHRIMALI SOC., NAVRANGPURA, AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380009 THEA0000000000A00179 306 ANJANA MANAN 101, AKSHAY, 53, SHRIMALI SOCIETY, NAVRANGPURA,, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380009 THEA0000000000A00217 11 ARJANBHAI ALABHAI 664 KUBERDAS MODI'S OLD CHAWAL, SAIJPUR BOGHA NARODA ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Maharashtra 444444 THEA0000000000A00203 1 BAKULA R JHAVERI 10 SEKHSARIA BUILDINGS, 2ND FLOOR, 448 SVP ROAD, , MUMBAI INDIA Maharashtra 400004 THEA0000000000B00168 1 BANK OF INDIA BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, BHADRA, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380001 THEA0000000000B00118 783 BHARATKUMAR SHIVJI SHETHIA 7/1 'TILOTTMA', 1-C PANKAJ MULLICK, SARANI (FORMALY RITCHIE ROAD), , CALCUTTA KOLKATA INDIA West Bengal 700019 THEA0000000000B00138 33 C V MEHTA PRIVATE LIMITED BANK OF BARODA BUILDING, GANDHI ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380001 THEA0000000000C00068 1 DR ARUNA RAMANLAL JHAVERI RAJAN SHRI NIWAS SOC., SUKHIPURA NEW SHARDA MANDIR ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380007 THEA0000000000A00086 1 DR JIVANLAL HUKAMCHANDJI PAREKH C/O.DHANRAJ & CO., RESHAM BAZAR ITWARI, , NAGPUR INDIA Maharashtra 444444 THEA0000000000J00051 13 DR SUMATILAL VIRCHAND MODI NO.1 NEW ANJALI SOCIETY, VASANA, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380007 -

ALTRIM-Catalogue-2018-21.Pdf

India & Southeast Asia Architectural Travel Guides CATALOGUE 2018-2021 Connecting local culture and architecture in a unique and surprising manner Indian Architectural Travel Guides NEW JAIPUR 230 pages Jaipur is a melting pot of Rajput, Mughal and several other cultures and is With 228 colour photographs, also the seat of a generous amount of vernacular tradition. The visitor will 22 maps and 102 plans also find a contemporary architecture infusing new forms with the legacy of 5 x 7.25” (126 x 184 mm) the past and the spirit of place. ISBN: 978-84-942342-4-8 Price: 25€ / 30$ / 22£ 7 itineraries, 166 buildings and places to visit, Buildings index list Jaipur’s bibliography Facts for the visitors chapter JAIPUR Talkatora TalkatoraSamode Haveli Anokhi Museum Samode Haveli Badrinath Temple Bihari ji ka Temple Panna Meena ka Kund Sagar Lake GOVIND DEV Srijagat Shiromaniji Temple Gaitore ki Chhatriyan Kale Hanumanji ka Mandir COLONY GOVIND DEV Kale Hanumanji ka Mandir COLONY Amber Palace Govind Devji Temple Maotha Lake Govind Devji Temple RAMCHANDRA CHAND MAHAL CHAUKARI COLONY Diwan-I-Khas Hawa Mahal Road RAMCHANDRA CHAUKARI Sawai Man Singh CHAND MAHAL Town Hall COLONY City Palace Diwan-I-Khas Hawa Mahal Road Sawai Man Singh Jantar Mantar Town Hall Tripolia Gate City Palace Sargasuli (Isarlat) Raghunathji Temple Hawa Mahal BADI CHAUPAR Jantar Mantar Way to Jaigarh, Govt. Public Library Nahargarh Fort Tripolia Gate Sargasuli (Isarlat) Raghunathji Temple Hawa Mahal BADI CHAUPAR Govt. Public Library Jal Mahal Jaipur JOHRI BAZAR Rajasthan School -

Ahmedabad City Map Pdf Free Download

Ahmedabad city map pdf free download Continue The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 613 X 814 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 121722. You can open this downloadable and printed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map of yourself or this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 557 X 775 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 163573. You can open, download and print this detailed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map yourself or by clicking on this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 1843 X 1405 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 317955. You can open this downloadable and printed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map of yourself or this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 3213 X 2436 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 577895. You can open, download and print this detailed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map yourself or by clicking on this link: Open the map. Car rental on OrangeSmile.com OrangeSmile.com is an expert on online travel booking, providing reliable services for car rental and hotel booking. We have more than 25,000 destinations with 12,000 rental offices and 200,000 hotels around the world. Secure Server Head Office Weegschaalstraat 3, Eindhoven 5632 CW, Netherlands No31 40 40 150 44 Privacy Policy Terms About Us Copyright © 2002 - OrangeSmile Tours B.V. OrangeSmile.com (OrangeSmile.com) Under the direction and direction of IVRA Holding B.V. -

City Wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/S GTPL Hathway, As Reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015

City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s GTPL Hathway, as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. Name of City S. No Name of State (Area of Name of Linked LCO Address of Linked LCO operation) 1 BIHAR PATNA B.S.V CABLE NETWORK PAHARPUR,POLICE COLONY, ANISABAD, PATNA, BIHAR, 0 2 BIHAR PATNA S.R CABLE NETWORK S/O LATE. SUNDAR PRASAD, SOUTH MANDIRIKATHPULPATNA, REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 3 BIHAR PATNA ANIKIT VISION DHANOOTRUPASPURPATNA, PATNA, REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 801506 4 BIHAR PATNA VINOD CABLE NETWORK S/O LAXMI MAHTONIKASH PIND, PATNACITYREENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800008 5 BIHAR PATNA ANMOL NAMAN CABLE NETWORK S/O LT.BRIJNANDAN PRASAD YADAVLODIPURKESHAVLAALROAD, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 6 BIHAR PATNA N‐BUDDHA CABLE NETWORK DUJRA PURBI GALIBUDDHA COLONYPATNA, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 7 BIHAR PATNA RANJAN ENTERPRISES DR.JANARDHAN GALINEAR PURANDAPUR JAKANPUR, , REENA VILLA SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800001 8 BIHAR PATNA M/S MADAN CABLE NETWORK PATNA NAGAR NIGAMSHEK BUCHER KA CHAURAHA, DURGA CHARAN LANE NEAR SHIV MANDIRP.O GULZARBAGH, PS‐ ALAM GUNJ PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800007 9 BIHAR PATNA MAA MANGLA GAURI CABLE LAXMI NIWAS KADAM KUAN CHORI MARKET, , REENA VILLA NETWORK SHANTINIKETAN, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800003 10 BIHAR PATNA ENTERTAINMENT CITY CABLE N/W DAHUA CHAK NAGLA, MALSALAMI, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, (RC BIHAR, 800008 11 BIHAR PATNA SONY MANORANJAN NETWORK BHAISANI TOLA, MALSALAMI, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, (RC) 800008 12 BIHAR PATNA PAWAN CABLE NETWORK(JMD) BADI NAGLA, MALSALAMIPATNA CITY, PATNA, PATNA, PATNA, BIHAR, 800008 City wise List of Linked Local Cable Operators of M/s GTPL Hathway, as reported to TRAI, on 25.05.2015. -

Life Membership 2011-18 Dec Telephone

LIFE MEMBERSHIP 2011-18 DEC TELEPHONE . Sl.No Name Designation ADDRESS NO SABZAZRE_NASEEBA-17,Muslim 1 A A MUNSHI HD Pharmasist soc. Navrangpura, AHMEDABAD 9979148439 380009. Gineshwar part - I Nr Kanti part 2 A B PANT EE(D) society,Ghatlodia Ahmedabad- 27604204 380061 B-32, Orchid park nr Shailby Hospital 3 A C Bajaj Mgr(Logistic) 9904981023 opp. Karnavati c;lub Satelite , A-22,Park Avenue New cg 4 A C Barua Dy.SE(P) 9427336696 roadChandkheda Ahmedabad-380005 22,Somvil Bunglows,Bhaikaka Nagar 5 A C Saini SE(P) Thaltej Ahmedabad-55 B-302.Chinubhai Tower Satelite 6 A D PATEL SE(P) 9428563893 Memnagar AHMEDABAD-52. 27,Konark Society Sabarmati 7 A D VAID DySE(E) 9898218428 Ahmedabad -380019 A-9 AL-Ashurfi Society,B/H Haider 8 A G SHAIKH AEE(P) Nagar, JUHAPAURA, Sarkhej Road 9428330591 AHMEDABAD 380055 B-27, Shardakrupa Society, B/H 9 A H Naik Dy. SE(P) Janatanagar Chandkheda, 27516085 GANDHINAGAR-382424. 66/7 Madini Chamber ,Mahakali 10 A I Shaikh AE(M) Temple Dudeshwar Shahibaug 9824591030 Ahmedabad 8 Sindhu Mahal soc. Ashram road Old 11 A J Sharma DM(HR) 9428008152 Vadaj Ahmedabad 380013. D-303 Aditya residency Motera 12 A K Dhawan GM(Res) 9428332121 Ahmedabad 380005. H-6,Karnavati Soc.GHB Chandkheda 13 A K GAHLAUT GM(P) 23296926 Ahmedabad-382424 Flat no 1001 Sangath Diomond 14 A K Gupta Exe.Director Tower nr PVR cinema Motera 9712922825 Ahmedabad 380005. 2nd floor Rituraj Apartment op Rupal 15 A K Gupta DGM(MM) flats nr Xavier Loyla school 9426612638 Ahmedabad B-77,RJESHWARI 09428330135- 16 A K MEHTA EE(M) SOCIETY,PO,TRAGAD,IOC ROAD 27508082 CHANDKHEDA AHMEDABAD-382470. -

Street Vendors in Ahmedabad: Status, Contribution and Challenges

a i d Street Vendors in Ahmedabad: Status, n I f o Contribution and Challenges t n e 9 0 m 0 n 0 r 8 e 3 v - o d a G , b a n o d i e t a m i h v e A l l , a A r y u t r p e g v n o a r P v n a y a t N i b s , r r d e U a v o i d n n R a U y t g i T n s i P r s e E u v i o C n H U f , o s y u r p t s i m a n i C i M a r h o f b l e a r t L n i e a h C b e r c u r t u s o a s e K Darshini Mahadevia R l Alison Brown a n Michal Lyons o i t Suchita Vyas a Kaushal Jajoo N Aseem Mishra CUE Working Paper 22 March 2013 Centre for Urban Equity (CUE) Street Vendors in Ahmedabad: Status, Contribution and Challenges Darshini Mahadevia Alison Brown Michal Lyons Suchita Vyas Kaushal Jajoo Aseem Mishra CUE Working Paper 21 March 2013 SEWA, Cardiff, ESRC, London South Banks University, DFID and Centre for Urban Equity- CEPT University About Centre for Urban Equity (CUE) CUE was established at CEPT University in 2009, evolving from the Urban Poverty Alleviation (UPA) Cell established in 2008. CUE advocates a human-centered and equitable urban development paradigm. -

Unclaim Account Reportas on 31-03-2021

ACCT NAME ADDRESS NATRAJ CLOTH STORES 23, PATEL CLOTH MARKET BAPUNAGAR AHD BHOLANATH VASTRA BHANDAR 11/12, PATEL CLOTH MARKET AHD STUDENT WELFARE TRUST OPP. KALYAN KENDRA,NEW BAPUNAR Ah d VISWAS CORPARATION VISWANATH BANGLOWS BIH. SHIVDARSHAN ODHAV ROAD Ahmedabad CELLO PAINTS IND 5-P D CORPORATION NR. REVABHA REVABHAI ESTATE C.T.M Ahmedabad NEWMAC AIR PRODUCTS 7-AMAR ESTATE NR.KANTA ESTATE Ahmedabad SHALIGRAM MOTOR INDUSTRIES D-77, INDRAJIT,MAHAVIRSOCIETY THAKKARBAPANAGAR Ahmedabad GAJARA ONERS ASOCIATION 493-MAHAVIRNAGARSOCIETY THHKARBAPANAGAR Ahmedabad SWATI ENTERPRISES SHRIJEE COMPLEX , NEAR SUKHRAM CHAMBER S, BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad MANOJ ELECTRONICS 30/3 VIRATNAGAR SOCIETY KHODIYARNAGAR Ahmedabad KINJAL SALES AGENCY 74/MAYURPARK SOC, BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad MANPASAND SINTHITEC 23/ PATEL CLOTH MARKET Ahmedabad SURAJ PROVISION STORS D-8/ NARAYANNAGAR PART-2 KHODIYARNAGAR AHMEDABAD METALAB ENTERPRISE 25/26, NILKANTH AVENUE, B/H PALM HOTEL SARDAR PATEL RING ROAD AVAS DEVLOPERS RATANBA VIDHAVAL NR. TAHHAKARBAPANAGAR Ahmedabad SOMANTH CORPORATION B-207 SHIVPARK SOCIETY ODHAV Ahmedabad SUKHARAM BILLDERS A-1 TWIN BUNGLOJ SOCIETY NICOLGAM ROAD Ahmedabad SARTHI BUILDERS GHANSYAMNAGAR NR. SANKET VIDH. BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad AKASH SPINNERS 8,MAMTA IND. ESTATE VASTRAL ROAD, AMRAIVADI Ahmedabad KRISHNA COMPUTER CENTER F/31-32 SARTHI COMPLEX JASODANAGAR CHOKDI Ahmedabad NEHA TEXTILES 12/ AVAKASH SOCIETY BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad SHREEJI CORPORATION NR. PANCHVATI SOCIETY THAKKARBAPA NAGAR ROAD Ahmedabad SHREE AAMBESHWER MOLDAS 31/ CHANDRA DYAMAND CENTER BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad KHODIYAR SALES CORPORATION SHAHAPURA TILES COMPOUND ODHAV ROAD Ahmedabad CHANDRAKANT BHAGVANBHAI PATEL 719, MAHAVIRNAGAR INDIA COLONY Ahmedabad KHODIYAR HANDLOOM HOUSE A-10, GOPINATH SOCIETY INDIA COLONY, BAPUNAGAR Ahmedabad SHRI UMIYA DECORETARS MANAHAR NAGAR PART-1, KHODIYAR NAGAR Ahmedabad PRAMUKH DEVLOPERS 703/4633 G.H. -

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY B.Ed. Online Centralized Admission

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY Gujarat University B.Ed.Admission Committee (GUBEDAC) B.Ed. Online Centralized Admission Information Booklet: 2019 - 2020 GUJARAT UNIVERSITY B.Ed. ADMISSION COMMITTEE (GUBEDAC) Room No. : 08 Department of Education School of Psychology,Education and Philosophy, Gujarat University,NAVRANGPURA, AHMEDABAD-380009. From the Desk of the Vice Chancellor Namaskar and Season’s Greetings! Many congratulations to you on your excellent academic journey so far. You are warmly welcome to the Gujarat University family. Since its inception in 1949 and banking on our glorious alumni tradition, the University strives to excel in various disciplines like Humanities, Management, Law, Education, Sciences, Medical and Paramedical. This e-booklet details various courses following the UGC and Government of Gujarat guidelines. The credit system for each subject is the core component of the education system at Gujarat University. This will be especially beneficial for those who wish to pursue higher studies at the institutes and universities of national and international repute. These programmes include wide range of core, compulsory, core electives, subject electives and soft skill and foundation courses. The motto of Gujarat University is Education-Innovation-Skill with Culture. The Gujarat University also provides a progressive platform to young entrepreneurs/researchers/scholars/faculties. The University has a strong and innovative initiativelike Gujarat University Startup and Entrepreneurship Council (GUSEC), Gujarat University Consultancy Cell (GUCC) and an upcoming APJ Abdul Kalam Centre for Extension, Research and Innovation (CERI), Research Park (RP), DST- Technology Business Incubator (TBI), Atal Incubation Centre (AIC). The affiliated colleges of this University also provide various opportunities and a platform to the students to blossom in curricular and extra-curricular activities like cultural, social, sports, NSS and NCC, etc. -

Shri Mahakali Beverages

+91-8048372464 Shri Mahakali Beverages https://www.indiamart.com/shri-mahakali-beverages/ Established in the year 2018 Ahmedabad, Gujarat “Shri Mahakali Beverages” are a Sole Proprietorship firm, engaged as the foremost Manufacturer of Svagat Drink, Packaged Drinking Water Bottle etc. About Us Established in the year 2018 Ahmedabad, Gujarat “Shri Mahakali Beverages” are a Sole Proprietorship firm, engaged as the foremost Manufacturer of Svagat Drink, Packaged Drinking Water Bottle etc. Our products are high in demand due to their premium quality and affordable prices. Furthermore, we ensure to timely deliver these products to our clients, through this we have gained a huge clients base in the market. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/shri-mahakali-beverages/aboutus.html PACKAGED DRINKING WATER BOTTLE O u r P r o d u c t s USP 500 ML Packaged USP 1 L Packaged Drinking Drinking Water Bottle Water Bottle Assure 250ml Packaged Yesh 250ml Packaged Drinking Water Bottle Drinking Water Bottle PACKAGED DRINKING WATER BOTTLE SET O u r P r o d u c t s USP 500ml Packaged Assure 1 Liter Packaged Drinking Water Bottle Set Drinking Water Bottle Set USP 1 L Packaged Drinking Yesh 1 L Packaged Drinking Water Bottle Set Water Bottle Set SVAGAT DRINK O u r P r o d u c t s Svagat Jeera Masala Drink Svagat Orange Drink Svagat Apple Drink Svagat Green Lemon Drink OTHER PRODUCTS O u r P r o d u c t s SVAGAT COLA DRINK ASSURE PACKAGED DRINKING WATER LA YESH 500ML PACKAGED USP 1 LTR PACKAGED DRINKING WATER DRINKING WATER O u r OTHER -

AHMEDABAD CITY TOUR 0 Nights / 1 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW

Tour Code : AKSR0144 Tour Type : Short Tours (domestic) 1800 233 9008 AHMEDABAD CITY TOUR www.akshartours.com 0 Nights / 1 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 1Cities 1Days 7Activities Highlights Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Gandhi Ashram - Hutheesing Jain Temple - Sidi Saiyad Mosque - Bhadra Fort - Ellis Bridge - Riverfront Flower Garden - Sanskar Kendra - Kankariya Lake SIGHTSEEINGS Hutheesing Jain Temple Ahmedabad The construction of the temple was initiated originally planned by Sheth Hutheesing Kesarisinh, a wealthy Ahmedabad trader who died at 49. The construction was supervised and completed by his wife Shethani Harkunvar Ba. The total cost was approximately Rs. 8 lakh then a major sum. The temple is dedicated to Lord Dharmanatha, the fifteenth Jain Tirthankar. The Hutheesing Temple was created a hundred and fifty years ago by hundreds of artisans during the time a terrible drought hit Gujarat State in India, compelling hundreds of skilled artisans to migrate to Ahmedabad in search of work. The only means of livelihood for these migrant artisans was the Hutheesing Temple which supported them for a period of years. The temple apart for its rich architectural is also known for rainwater harvesting structure. Gandhi Ashram Ahmedabad Mahatma Gandhi established this Ashram in 17 June 1917. Gandhiji had driven all the major activities of independence as well as upliftment of the society from this Ashram which was popularly known as Sabarmati Ashram. He stayed in the ashram for Thirteen years before he finally proceeded for a march to Dandi to break the salt law on 12 March 1930.