Jm-12-47-1993.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordovician Land Plants and Fungi from Douglas Dam, Tennessee

PROOF The Palaeobotanist 68(2019): 1–33 The Palaeobotanist 68(2019): xxx–xxx 0031–0174/2019 0031–0174/2019 Ordovician land plants and fungi from Douglas Dam, Tennessee GREGORY J. RETALLACK Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA. *Email: gregr@uoregon. edu (Received 09 September, 2019; revised version accepted 15 December, 2019) ABSTRACT The Palaeobotanist 68(1–2): Retallack GJ 2019. Ordovician land plants and fungi from Douglas Dam, Tennessee. The Palaeobotanist 68(1–2): xxx–xxx. 1–33. Ordovician land plants have long been suspected from indirect evidence of fossil spores, plant fragments, carbon isotopic studies, and paleosols, but now can be visualized from plant compressions in a Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian or 460 Ma) sinkhole at Douglas Dam, Tennessee, U. S. A. Five bryophyte clades and two fungal clades are represented: hornwort (Casterlorum crispum, new form genus and species), liverwort (Cestites mirabilis Caster & Brooks), balloonwort (Janegraya sibylla, new form genus and species), peat moss (Dollyphyton boucotii, new form genus and species), harsh moss (Edwardsiphyton ovatum, new form genus and species), endomycorrhiza (Palaeoglomus strotheri, new species) and lichen (Prototaxites honeggeri, new species). The Douglas Dam Lagerstätte is a benchmark assemblage of early plants and fungi on land. Ordovician plant diversity now supports the idea that life on land had increased terrestrial weathering to induce the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event in the sea and latest Ordovician (Hirnantian) -

Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, South-West Libya

This is a repository copy of Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, south-west Libya. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125997/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Abuhmida, F.H. and Wellman, C.H. (2017) Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, south-west Libya. Palynology, 41. pp. 31-56. ISSN 0191-6122 https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2017.1356393 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, southwest Libya Faisal H. Abuhmidaa*, Charles H. Wellmanb aLibyan Petroleum Institute, Tripoli, Libya P.O. Box 6431, bUniversity of Sheffield, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, Alfred Denny Building, Western Bank, Sheffield, S10 2TN, UK Twenty nine core and seven cuttings samples were collected from two boreholes penetrating the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, southwest Libya. -

A Chemostratigraphic Investigation of the Late Ordovician Greenhouse to Icehouse Transition: Oceanographic, Climatic, and Tectonic Implications

A CHEMOSTRATIGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF THE LATE ORDOVICIAN GREENHOUSE TO ICEHOUSE TRANSITION: OCEANOGRAPHIC, CLIMATIC, AND TECTONIC IMPLICATIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Seth Allen Young, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Matthew R. Saltzman, Adviser Dr. Kenneth A. Foland Dr. William I. Ausich Dr. Andrea G. Grottoli ABSTRACT The latest Ordovician (444 million years ago) was a critical period in Earth history. This was a time of significant climatic global change with large-scale continental glaciation. Moreover, the end-Ordovician mass extinction is recognized as the second- most devastating mass extinction to have affected the Earth. The anomalous Late Ordovician icehouse period has perplexed many researchers because all previous model and proxy climate evidence suggest high levels of atmospheric CO2 during the Late Ordovician glaciation. Also associated with this period is a large positive carbon isotope (δ13C) excursion (up to +7‰) that represents a global perturbation of the carbon cycle. Additionally, a large decrease (0.001) in seawater 87Sr/86Sr occurs several million years prior (~460 million years ago); this could reflect an increase in atmospheric CO2 uptake due to weathering of volcanic rocks involved in uplift of the early Appalachian Mountains. To address these Ordovician anomalies, well-studied, thick, and continuous Late Ordovician limestone sequences from eastern West Virginia, south-central Oklahoma, central Nevada, Quebec (Canada), Estonia, and China have been sampled. Carbon and strontium isotopic ratios have been measured on samples from these localities of which Estonian and Chinese sample sites represent separate paleocontinents (Baltica and South ii China) and are compared with other data sets from North America. -

Katian-Hirnantian

Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 244 (2017) 217–240 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/revpalbo Cryptospore and trilete spore assemblages from the Late Ordovician (Katian–Hirnantian) Ghelli Formation, Alborz Mountain Range, Northeastern Iran: Palaeophytogeographic and palaeoclimatic implications Mohammad Ghavidel-Syooki Institute of Petroleum Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Tehran, P.O. Box: 11155/4563, Tehran, Iran article info abstract Article history: Well-preserved miospore assemblages are recorded from the Late Ordovician (Katian–Hirnantian) Ghelli Formation Received 4 March 2015 in the Pelmis Gorge, located in the Alborz Mountain Range, Northeastern Iran. The palynomorphs were extracted Received in revised form 29 March 2016 from siliciclastic deposits that are accurately dated using marine palynomorphs (acritarchs and chitinozoans). Accepted 9 April 2016 The spore assemblages consist of 14 genera and 28 species (26 cryptospores and 2 trilete spore species). Six Available online 15 June 2017 new cryptospore species are described: Rimosotetras punctata n.sp., Rimosotetras granulata n.sp., Dyadospora Keywords: asymmetrica n.sp., Dyadospora verrucata n.sp., Segestrespora iranense n.sp., and Imperfectotriletes persianense Cryptospores n.sp. The study furthers knowledge of the development of the vegetative cover during the Late Ordovician. Late Ordovician Various and abundant cryptospores in the Late Ordovician (Katian–Hirnantian) Ghelli Formation are probably Palaeo-biogeography related to the augmentation of land-derived sediments either during the global sea-level fall linked to the Late Palaeo-climatology Ordovician glaciation or adaptation of the primitive land plants in a wide range of climatic conditions. These Alborz Mountain Range miospore taxa were produced by the earliest primitive land plants, which probably grew close to the shoreline Northeastern Iran and were washed in from adjacent areas, producing a high volume of miospores. -

Early Middle Ordovician Evidence for Land Plants in Argentina (Eastern Gondwana)

New Phytologist Research Rapid report Early Middle Ordovician evidence for land plants in Argentina (eastern Gondwana) Author for correspondence: C. V. Rubinstein1, P. Gerrienne2, G. S. de la Puente1, R. A. Astini3 and Claudia V. Rubinstein 2 Tel: +54 261 5244217 P. Steemans Email: [email protected] 1Unidad de Paleopalinologı´a, Departamento de Paleontologı´a, Instituto Argentino de Nivologı´a, Received: 30 June 2010 Glaciologı´a y Ciencias Ambientales, CCT CONICET – Mendoza, A. Ruiz Leal s ⁄ n, Parque General Accepted: 19 July 2010 San Martı´n, 5500 Mendoza, Argentina; 2Pale´obotanique, Pale´opalynologie, Micropale´ontologie (PPM), Department of Geology, University of Lie`ge, B-18, Sart Tilman, BE–4000 Lie`ge 1, Belgium; 3Laboratorio de Ana´lisis de Cuencas, Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Tierra, CONICET- Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba. Pabello´n Geologı´a, Ciudad Universitaria, 2º Piso, Oficina 7, Av. Ve´lez Sa´rsfield 1611, X5016GCA-Co´rdoba, Argentina Summary New Phytologist (2010) 188: 365–369 • The advent of embryophytes (land plants) is among the most important evolu- doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03433.x tionary breakthroughs in Earth history. It irreversibly changed climates and biogeo- chemical processes on a global scale; it allowed all eukaryotic terrestrial life to Key words: cryptospores, embryophytes, evolve and to invade nearly all continental environments. Before this work, the evolution, Gondwana, land plants, Middle earliest unequivocal embryophyte traces were late Darriwilian (late Middle Ordovician, origin. Ordovician; c. 463–461 million yr ago (Ma)) cryptospores from Saudi Arabia and from the Czech Republic (western Gondwana). • Here, we processed Dapingian (early Middle Ordovician, c. -

Type of the Paper (Article

life Article Dynamics of Silurian Plants as Response to Climate Changes Josef Pšeniˇcka 1,* , Jiˇrí Bek 2, Jiˇrí Frýda 3,4, Viktor Žárský 2,5,6, Monika Uhlíˇrová 1,7 and Petr Štorch 2 1 Centre of Palaeobiodiversity, West Bohemian Museum in Pilsen, Kopeckého sady 2, 301 00 Plzeˇn,Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology, Geological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rozvojová 269, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (V.Ž.); [email protected] (P.Š.) 3 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 21 Praha 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Czech Geological Survey, Klárov 3/131, 118 21 Prague 1, Czech Republic 5 Department of Experimental Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viniˇcná 5, 128 43 Prague 2, Czech Republic 6 Institute of Experimental Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, v. v. i., Rozvojová 263, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic 7 Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Albertov 6, 128 43 Prague 2, Czech Republic * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-733-133-042 Abstract: The most ancient macroscopic plants fossils are Early Silurian cooksonioid sporophytes from the volcanic islands of the peri-Gondwanan palaeoregion (the Barrandian area, Prague Basin, Czech Republic). However, available palynological, phylogenetic and geological evidence indicates that the history of plant terrestrialization is much longer and it is recently accepted that land floras, producing different types of spores, already were established in the Ordovician Period. -

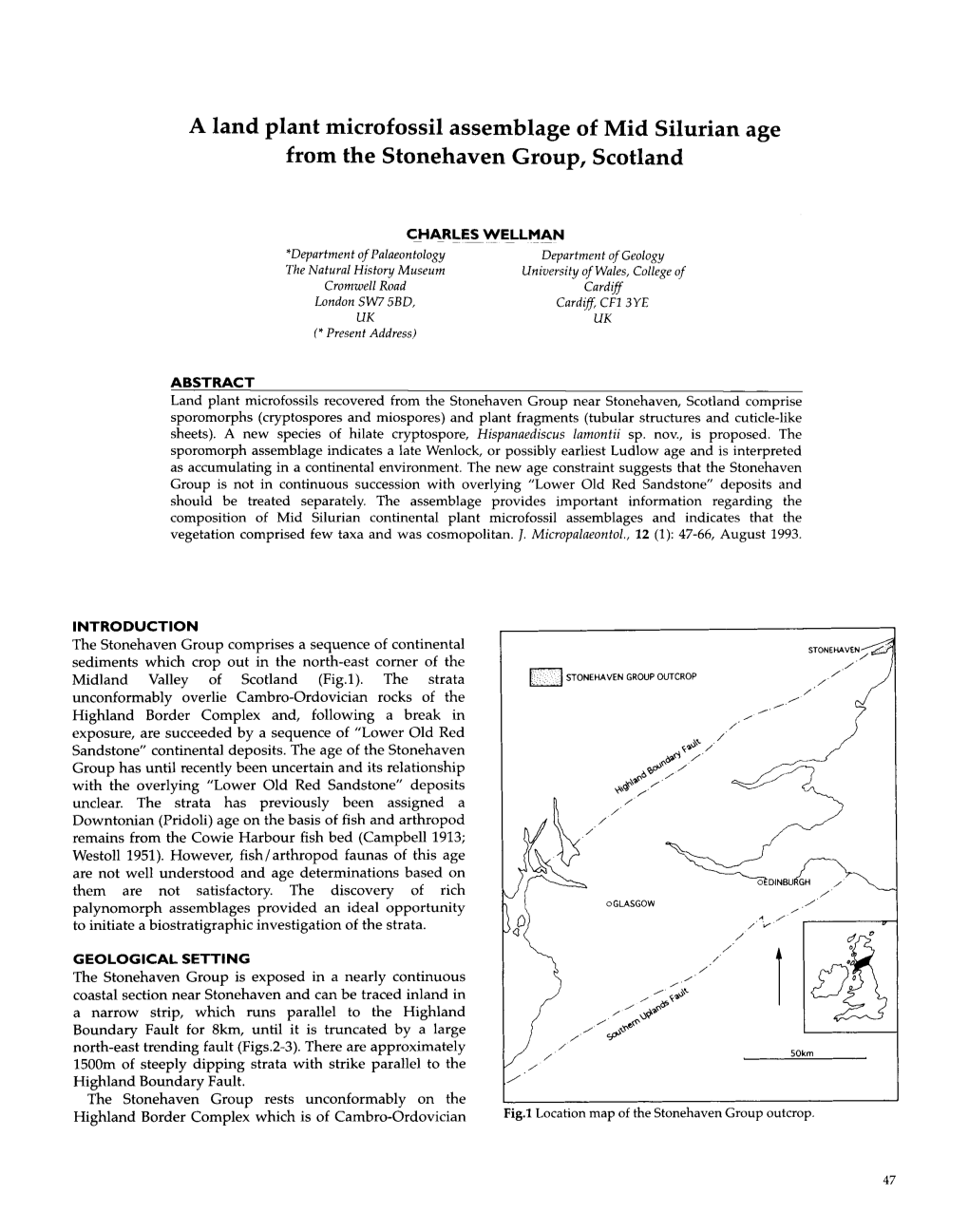

The Terrestrialization Process: a Palaeobotanical and Palynological Perspective Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud, Thomas Servais, Marco Vecoli, Philippe Gerrienne

The terrestrialization process: A palaeobotanical and palynological perspective Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud, Thomas Servais, Marco Vecoli, Philippe Gerrienne To cite this version: Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud, Thomas Servais, Marco Vecoli, Philippe Gerrienne. The terrestrialization process: A palaeobotanical and palynological perspective. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Elsevier, 2016, The terrestrialization process : a palaeobotanical and palynological perspective - volume 1, 224 (1), pp.1-3. 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.10.011. hal-01278369 HAL Id: hal-01278369 https://hal-sde.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01278369 Submitted on 26 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 224 (2016) 1–3 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/revpalbo The terrestrialization process: A palaeobotanical and palynological perspective Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud a,⁎,ThomasServaisb,MarcoVecolic,PhilippeGerrienned a CNRS, Université de Montpellier, Botanique -

Servais Et Al. 2019.Pdf

Revisiting the Great Ordovician Diversification of land plants: Recent data and perspectives Thomas Servais, Borja Cascales-Miñana, Christopher Cleal, Philippe Gerrienne, David A.T. Harper, Mareike Neumann To cite this version: Thomas Servais, Borja Cascales-Miñana, Christopher Cleal, Philippe Gerrienne, David A.T. Harper, et al.. Revisiting the Great Ordovician Diversification of land plants: Recent data and per- spectives. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Elsevier, 2019, 534, pp.109280. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109280. hal-03046718 HAL Id: hal-03046718 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03046718 Submitted on 22 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2 3 Revisiting the great Ordovician diversification of land plants: 4 recent data and perspectives 5 6 7 Thomas Servaisa*, Borja Cascales-Miñanaa, Christopher J. Clealb, Philippe Gerriennec, 8 David A.T. Harperd, Mareike Neumanne,f 9 10 a CNRS, University of Lille, UMR 8198 - Evo-Eco-Paleo, F-59000 Lille, France 11 b Department of Natural Sciences, National Museum Wales, Cardiff, CF10 3NP, UK 12 c EDDy Lab, Department of Geology, University of Liege, B18 Sart Tilman, B-4000 Liege, 13 Belgium 14 d Palaeoecosystems Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham DH1 15 3LE, United Kingdom 16 e Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Hans-Knoell-Straße 10, 07745 Jena, Germany 17 f MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, 18 Leobenerstraße 8, 28359 Bremen, Germany 19 20 * Corresponding author. -

Supplementary Information 1. Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Information 1. Supplementary Methods Phylogenetic and age justifications for fossil calibrations The justifications for each fossil calibration are presented here for the ‘hornworts-sister’ topology (summarised in Table S2). For variations of fossil calibrations for the other hypothetical topologies, see Supplementary Tables S1-S7. Node 104: Viridiplantae; Chlorophyta – Streptophyta: 469 Ma – 1891 Ma. Fossil taxon and specimen: Tetrahedraletes cf. medinensis [palynological sample 7999: Paleopalynology Unit, IANIGLA, CCT CONICET, Mendoza, Argentina], from the Zanjón - Labrado Formations, Dapinigian Stage (Middle Ordovician), at Rio Capillas, Central Andean Basin, northwest Argentina [1]. Phylogenetic justification: Permanently fused tetrahedral tetrads and dyads found in palynomorph assemblages from the Middle Ordovician onwards are considered to be of embryophyte affinity [2-4], based on their similarities with permanent tetrads and dyads found in some extant bryophytes [5-7] and the separating tetrads within most extant cryptogams. Wellman [8] provides further justification for land plant affinities of cryptospores (sensu stricto Steemans [9]) based on: assemblages of permanent tetrads found in deposits that are interpreted as fully terrestrial in origin; similarities in the regular arrangement of spore bodies and size to extant land plant spores; possession of thick, resistant walls that are chemically similar to extant embryophyte spores [10]; some cryptospore taxa possess multilaminate walls similar to extant liverwort spores [11]; in situ cryptospores within Late Silurian to Early Devonian bryophytic-grade plants with some tracheophytic characters [12,13]. The oldest possible record of a permanent tetrahedral tetrad is a spore assigned to Tetrahedraletes cf. medinensis from an assemblage of cryptospores, chitinozoa and acritarchs collected from a locality in the Rio Capillas, part of the Sierra de Zapla of the Sierras Subandinas, Central Andean Basin, north-western Argentina [1]. -

The First Report of Cryptospore Assemblages of Late Ordovician in Iran, Ghelli Formation, Eastern Alborz

Geopersia 4 (2), 2014, PP. 125-140 The first report of cryptospore assemblages of Late Ordovician in Iran, Ghelli Formation, Eastern Alborz Maryam Mahmoudi1, Jafar Sabouri2*, Habib Alimohammadian3, Mahmoud Reza Majidifard1 1 Geoscience Research Center, Geological survey of Iran, Tehran, Iran 2 Ferdowsi University of Mashhad International Campus 3 Enviromental and Paleomagnetic Laboratory, Geological survey of Iran, Tehran *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] (received: 31/05/2014 ; accepted: 08/12/2014) Abstract For the first time, an assemblage of cryptospores, which includes 10 species belonging to nine genera, from the Upper Ordovician strata, is being reported, in Iran. These cryptospore assemblages were recovered from the upper part of Ghelli Formation., from the eastern Alborz Mountain range. These peri-Gondwanan cryptospores have been classified based on their morphology (monad, true dyad, pseudodyad, true attached, and loose tetrads). The results of the present study support previous findings that there are no significant differences between similar-aged cryptospore assemblages of the peri-Gondwanan, Baltic provinces and other parts of the world. Based on the presence of the chitinozoan index of the northern Gondwana (Spinachitina oulebsiri), the index acritarchs, and the present cryptospores, a late Hirnantian (Late Ordovician) age is proposed to the top of the Ghelli Formation. The cryptospores seem to be transported from an adjacent land area and the lack of land-derived elements in the up-section may indicate an increased distance offshore. Keywords: Cryptospore, Late Ordovician, Ghelli Formation, Eastern Alborz, Iran. Introduction The Ghelli Formation (Abarsaj formation) was The study area is located about 80 km north-east of first introduced by Shahrabi (1990) in the Gorgan the city of Shahroud and east of the Khosh-Yeilaghi geological map (scale 1:250000). -

Strother.Pdf

Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 227 (2016) 28–41 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/revpalbo Systematics and evolutionary significance of some new cryptospores from the Cambrian of eastern Tennessee, USA Paul K. Strother ⁎ Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Boston College Weston Observatory, 381 Concord Road, Weston, MA 02493, USA article info abstract Article history: The highly bioturbated mudstones of the uppermost Rome Formation and the Conasauga Group in eastern Tennes- Received 3 June 2015 see contain an extensive palynoflora that consists primarily of nonmarine, spore-like microfossils, which are treat- Received in revised form 24 September 2015 ed systematically as cryptospores because they present characters that are consistent with a charophytic origin. Accepted 9 October 2015 The following new taxa are proposed: Adinosporus voluminosus, Adinosporus bullatus, Adinosporus geminus, Available online 3 November 2015 Spissuspora laevigata,andVidalgea maculata. The lamellated wall ultrastructure of some of these cryptospores Keywords: appears to be homologous to extant, crown group sphaerocarpalean liverworts and to the more basal genus, — Laurentia Haplomitrium. There is direct evidence that some of these cryptospores developed via endosporogenesis entirely Palynology within the spore mother cell wall. The topology of enclosed spores indicates that the meiotic production of spore Origin of land plants dyads represents the functional spore end-members, but the diaspore itself appears to be a spore packet corre- Rogersville Shale sponding to the contents of each original spore mother cell. Aeroterrestrial charophytes of this time period Successive meiosis underwent sporogenesis via successive meiosis rather than simultaneous meiosis. -

Baltica Cradle of Early Land Plants? Oldest Record of Trilete Spores and Diverse Cryptospore Assemblages; Evidence from Ordovician Successions of Sweden

GFF ISSN: 1103-5897 (Print) 2000-0863 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/sgff20 Baltica cradle of early land plants? Oldest record of trilete spores and diverse cryptospore assemblages; evidence from Ordovician successions of Sweden Claudia V. Rubinstein & Vivi Vajda To cite this article: Claudia V. Rubinstein & Vivi Vajda (2019) Baltica cradle of early land plants? Oldest record of trilete spores and diverse cryptospore assemblages; evidence from Ordovician successions of Sweden, GFF, 141:3, 181-190, DOI: 10.1080/11035897.2019.1636860 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2019.1636860 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 24 Jul 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 604 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=sgff20 GFF 2019, VOL. 141, NO. 3, 181–190 https://doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2019.1636860 ARTICLE Baltica cradle of early land plants? Oldest record of trilete spores and diverse cryptospore assemblages; evidence from Ordovician successions of Sweden Claudia V. Rubinsteina and Vivi Vajdab* aDepartment of Paleopalynology, IANIGLA, CCT CONICET Mendoza, M5502IRA, Mendoza, Argentina; bDepartment of Paleobiology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The origin of land plants is one of the most important evolutionary events in Earth’s history. The mode and Received 16 June 2019 timing of the terrestrialization of plants remains debated and previous data indicate Gondwana to be the Accepted 24 June 2019 ~ – center of land-plant radiation at 470 460 Ma.