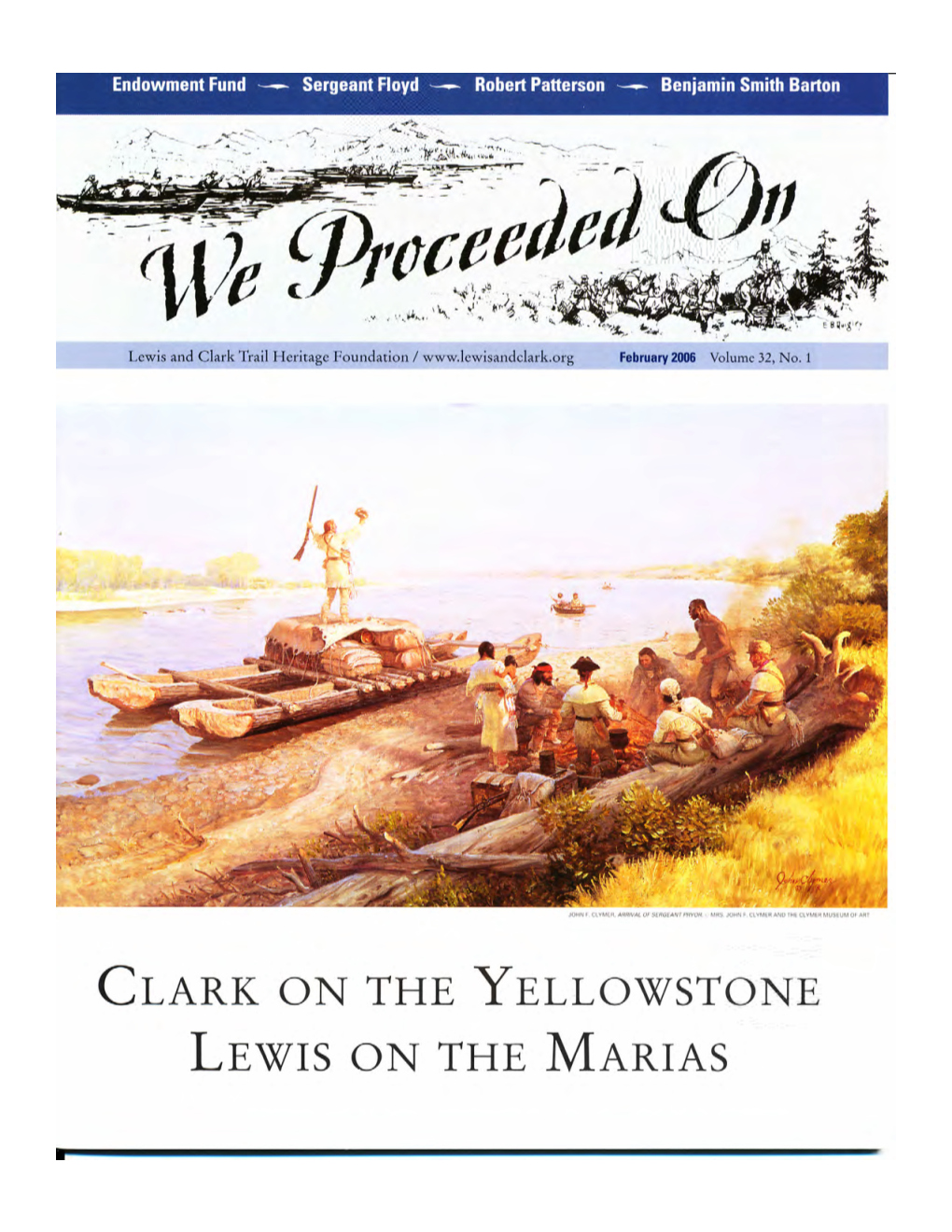

February 2006, Vol. 32 No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIANS DISCOVERING LEWIS and CLARK Oil Painting by C

INDIANS DISCOVERING LEWIS AND CLARK Oil Painting by C. M. Russell Montana Historical Society, Mackay Collection THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. President Incorporated 1969 under Missouri General Not-For-Profit Corporation Act IRS Exemption Certificate No. 501 (C)(3) - Identification No. 51-0187715. Montague~s OFFICERS - EXECUTIVE COMMITIEE President 1st Vice President 2nd Vice President message H. John Montague Donald F. Nell Robert K. Doerk, Jr. 2928 N.W. Verde Vista Terrace P.O. Box577 P.O. Box 50ll Portland, OR 97210 Bozeman, MT 59715 Great Falls, MT 59403 Edrie Lee Vinson, Secretary John E. Walker, Treasurer 1405 Sanders 200 Market St., Suite 1177 Helena, MT 59601 Portland, OR 97201 By any measure, the 19th Annual Meeting Marcia Staigmiller, Membership Secretary of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foun RR 4433; Great Falls, MT 59401 dation was a resounding success. Sincere DIRECTORS thanks and commendations seem inadequate Ruth Backer James R. Fazio Ralph H. Rudeen in reviewing the efforts by our hosts, John Cranford, NJ Moscow, ID Olympia, WA and Pat Foote. They presented a wonderful opportunity to pursue the objectives of the Raymond L. Breun Harry Fritz Arthur F. Shipley St. Louis, MO Missoula, MT Bismarck, ND Foundation. During the visits to the expedi tion campsites and the float trip down the Patti A. Thomsen Malcolm S. Buffum James P. Ronda Waukesha, WI Yellowstone River, one could empathize with Portland, OR Youngstown, OH Captain Clark and his party as they pro Winifred C. George John E. Foote, Immediate Past President ceeded down the Yellowstone River to its St. -

Lewis and Clark: Rockhounding on the Way to the Pacific

Lewis and Clark: Rockhounding on the Way to the Pacific Copyright © 2004 by the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expe- dition, 13 volumes and an abridged edition. Edited by Gary E. Moulton. Lincoln, Nebraska: The University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001. The first volume is the oversized atlas, the last an index. Each volume has a separate subtitle. American Federation of Mineralogical Societies Brenda J. Hankins, Editor 2004 Table of Contents The Rockhound Hobby........................................................................................1 About this Publication............................................................................................1 Sites and Dates Covered........................................................................................3 Camp River DuBois, Wood River, IL...........................................................5 Lewis and Clark Word Find—Word Puzzle #1...................................8 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, MO...................9 Katy Trail State Park, Rocheport, MO.....................................................10 Independence Creek, Atchison, KS...............................................................12 Sergeant Floyd Monument, Sioux City, IA..............................................13 Lewis and Clark Word Search—Word Puzzle #2............................15 Ponca State Park, Ponca, NE...........................................................................16 -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Following in Their Footsteps: Creating the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, by Wallace G. Lewis

WashingtonHistory.org FOLLOWING IN THEIR FOOTSTEPS Creating the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail By Wallace G. Lewis COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Summer 2002: Vol. 16, No. 2 In May 1961 conservationist and celebrated political cartoonist for the Des Moines Register, J. N. "Ding" Darling, proposed that the Missouri River be incorporated into "a national outdoor recreation and natural resources ribbon along the historic trail of Lewis and Clark." Gravely ill, Darling knew he would not live to see such a project carried out, but he secured banker and fellow conservationist Sherry Fisher's promise to initiate a campaign for it. Darling, who had briefly served President Franklin D. Roosevelt as chief of the Biological Survey, was famous for his syndicated editorial cartoons promoting wildlife sanctuaries and opposing dam construction, particularly on his beloved Missouri River, and had been a major founder of the National Wildlife Federation. Following his friend's death in February 1962, Sherry Fisher helped form the J. N. "Ding" Darling Foundation, which he steered toward creation of a Lewis and Clark trail corridor that would also provide habitat for wildlife. Encouraged by Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, representatives of the foundation, federal agencies, and the states through which the Lewis and Clark trail passed met in Portland, Oregon, in the fall of 1962 to discuss the Darling proposal. Congress approved a trail plan in principle in 1963, and the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation began to study development along a ten-mile corridor for inclusion in a proposed nationwide system of scenic trails. On October 6, 1964, Public Law 88-630 was passed authorizing creation of a Lewis and Clark Trail Commission to promote public understanding of the expedition's historical significance and to review proposals for developing "desirable long-term conservation objectives" and recreation opportunities along its length. -

FIELDREPORT Northern Rockies | Summer 2015

FIELDREPORT Northern Rockies | Summer 2015 Sacred Ground A Lasting Legacy for Grand Teton Protecting the “Backbone of the World” By Sharon Mader Efforts to transfer ownership of state lands to Grand Teton Program Manager the Park Service are well underway, but are he Blackfeet Nation first encountered bound by an extremely ambitious timeline. Summer Celebration for Glacier’s North Fork the United States government in the resident Obama has an amazing The clock is ticking, and without immediate Tearly morning chill of July 27, 1806. opportunity, before the end of his action at the highest levels of government, Capt. Meriwether Lewis, returning with presidency, to create a profound his men from the Pacific, chanced upon P and lasting legacy for America’s national a band of eight young braves, camped in parks. As we look toward the Centennial spectacular buffalo country where unbroken of the National Park Service in August prairie crashes headlong into soaring 2016—NPCA is encouraging the peaks. What unfolded that morning was administration to prioritize protecting the only bloodshed recorded by Lewis lands in Grand Teton National Park that and Clark. are owned by the state of Wyoming. Before the summer sun had climbed high enough to warm the gravel banks of the More than 1,200 acres of state-owned Two Medicine River, two young Blackfeet lands fall within the boundary of the men—boys, really—were killed. park. These inholdings offer some of the most spectacular scenery and wildlife- Two centuries later, in 1982, the US viewing opportunities imaginable. Driving it’s possible this deal will not be completed in government returned to those very same by these lands, travelers assume these time. -

2013 NOV - I AM 19 REGIONS 8: R:·L L

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY 2013 NOV - I AM 19 REGIONS 8: r:·l L. ·1 . •- ..J Docket No. CWA-08-2014-0004 CPA HEGIOU VIII pr A~' l ~lc; CL FRI~ In the Matter of: ) ) Nelcon, Inc. ) ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER 304 Jellison Road ) FOR COMPLIANCE ON CONSENT Kalispell, Mt. 59903, ) ) Respondent. ) INTRODUCTION 1. This Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent (Consent Order) is entered into voluntarily by Nelcon, Inc. (Respondent) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA has authority to issue this Consent Order pursuant to section 309(a) of the Clean Water Act (Act), 33 U.S.C. § 1319(a), which authorizes the Administrator of the EPA to issue an order requiring compliance by a person found to be in violation of, inter alia, section 301(a) of the Act. This authority has been properly delegated to the undersigned EPA official. 2. The Findings in paragraph numbers 7 through 44 below are made solely by the EPA. In signing this Consent Order, and for that limited purpose only, Respondent neither admits nor denies the Findings. 3. Without any admission of liability, Respondent consents to issuance of this Consent Order and agrees to abide by all of its conditions. Respondent waives any and all remedies, claims for relief, and otherwise available rights to judicial or administrative review that Respondent may have with respect to any issue of fact or law set forth in this Consent Order, including any right ofjudicial review of this Consent Order under the Administrative Procedure Page 1 of 12 Act, 5 U.S.C. -

Compiled by C.J. Harksen and Karen S. Midtlyng Helena, Montana June

WATER-RESOURCES ACTIVITIES OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IN MONTANA, OCTOBER 1989 THROUGH SEPTEMBER 1991 Compiled by C.J. Harksen and Karen S. Midtlyng U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 91-191 Prepared in cooperation with the STATE OF MONTANA AND OTHER AGENCIES Helena, Montana June 1991 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, JR., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Jooks and Open-File Reports Section 428 Federal Building federal Center, Building 810 301 South Park, Drawer 10076 iox 25425 Helena, MT 59626-0076 Denver, CO 80225-0425 CONTENTS Page Message from the District Chief. ....................... 1 Abstract ................................... 3 Basic mission and programs .......................... 3 U.S. Geological Survey ........................... 3 Water Resources Division .......................... 4 District operations. ............................. 4 Operating sections ............................. 5 Support units. ............................... 5 Office addresses .............................. 5 Types of funding .............................. 8 Cooperating agencies ............................ 10 Hydrologic conditions ............................ 10 Data-collection programs ........................... 13 Surface-water stations (MT001) ....................... 16 Ground-water stations (MT002)........................ 17 Water-quality stations (MT003) ...................... -

Cut Bank Report

MONTANA RURAL DEVELOPMENT PARTNERS, INC. Rural Resource Team Report Cut Bank, Montana Glacier County January 22, 23 & 24, 2002 MT RDP Mission As our Mission, the Montana Rural Development Partners, Inc. is committed to supporting locally conceived strategies to sustain, improve, and develop vital and prosperous rural Montana communities by encouraging communication, coordination, and collaboration among private, public and tribal groups. THE MONTANA RURAL DEVELOPMENT PARTNERS, INC. The Montana Rural Development Partners, Inc. is a collaborative public/private partnership that brings together six partner groups: local government, state government, federal government, tribal governments, non-profit organizations and private sector individuals and organizations. An Executive Committee representing the six partner groups governs MT RDP, INC. The Executive Committee as well as the Partners’ membership has established the following goals for the MT RDP, Inc.: Assist rural communities in visioning and strategic planning Serve as a resource for assisting communities in finding and obtaining grants for rural projects Serve and be recognized as a neutral forum for identification and resolution of multi-jurisdictional issues. The Partnership seeks to assist rural Montana communities with their needs and development efforts by matching the technical and financial resources of federal, state, and local governments and the private sector with locally conceived strategies/efforts. If you would like more information about the Montana Rural Development Partners, Inc. and how you may benefit as a member, contact: Gene Vuckovich, Executive Director Montana Rural Development Partners, Inc. 118 East Seventh Street; Suite 2A Anaconda, Montana 59711 Ph: 406.563.5259 Fax: 406.563.5476 [email protected] http://www.mtrdp.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The elements are all here for Cut Bank to have a successful future. -

National Historic Landmarks Geology

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS Dr. Harry A. Butowsky GEOLOGY THEME STUDY Page 1 Geology National Historic Landmark Theme Study (Draft 1990) Introduction by Dr. Harry A. Butowsky Historian, History Division National Park Service, Washington, DC The Geology National Historic Landmark Theme Study represents the second phase of the National Park Service's thematic study of the history of American science. Phase one of this study, Astronomy and Astrophysics: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study was completed in l989. Subsequent phases of the science theme study will include the disciplines of biology, chemistry, mathematics, physics and other related sciences. The Science Theme Study is being completed by the National Historic Landmarks Survey of the National Park Service in compliance with the requirements of the Historic Sites Act of l935. The Historic Sites Act established "a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the American people." Under the terms of the Act, the service is required to survey, study, protect, preserve, maintain, or operate nationally significant historic buildings, sites & objects. The National Historic Landmarks Survey of the National Park Service is charged with the responsibility of identifying America's nationally significant historic property. The survey meets this obligation through a comprehensive process involving thematic study of the facets of American History. In recent years, the survey has completed National Historic Landmark theme studies on topics as diverse as the American space program, World War II in the Pacific, the US Constitution, recreation in the United States and architecture in the National Parks. -

Proceedings for Science, Policy and Communication: the Role of Science in a Changing World

Proceedings for Science, Policy and Communication: The role of science in a changing world American Water Resources Association Montana Section 2017 Conference October 18 - October 20, 2017 Great Northern Hotel -- Helena, Montana Contents Thanks to Planners and Sponsors Full Meeting Agenda About the Keynote Speakers Concurrent Session and Poster Abstracts* Session 1. Surface Water Session 2. Science, Policy and Communication Session 3. Forestry Session 4. Ground Water Session 5. Restoration Session 6. Water Quality Session 7. Water Data Systems and Information Session 8. Models, Water Quality and Geochemistry Poster Session *These abstracts were not edited and appear as submitted by the author, except for some changes in font and format. 1 THANKS TO ALL WHO MAKE THIS EVENT POSSIBLE! • The AWRA Officers Aaron Fiaschetti, President -- Montana DNRC Emilie Erich Hoffman, Vice President -- Montana DEQ Melissa Schaar, Treasurer -- Montana DEQ Nancy Hystad, Executive Secretary -- Montana State University • Montana Water Center, Meeting Coordination Whitney Lonsdale And especially the conference presenters, field trip leaders, moderators, student judges and volunteers. Aaron Fiaschetti Emilie Erich Hoffman Melissa Schaar Nancy Hystad 2 A special thanks to our generous conference sponsors! 3 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2017 REGISTRATION 9:30 am – 7:00 pm REGISTRATION Preconference registration available at http://www.montanaawra.org/ WORKSHOP, FIELD TRIP and HYDROPHILE RUN 10:00 am - 12:00 pm Workshop: Science and Public Collaboration Led by Susan Gilbertz, Oriental Ltd. Room 1:00 pm – 5:00 pm Field Trip: Canyon Ferry - Present, Past Led by Melissa Schaar, MT DEQ and AWRA Treasurer Bus leaves Great Northern Hotel promptly at 1 pm, returns at 5 pm 5:40 pm – 7:00 pm Hydrophile 5k Run/Walk Meet at field trip bus drop off location at 5:40 or 301 S. -

Mr. Budd's Historical Expeditions

Mr. Budd’s Historical Expeditions Randal O’Toole n 1925 and 1926, the Great North- ern Railway sponsored two trips Iunlike any rail tours before or since. In preparation, the railway erected six historic monuments that remain to this day, commissioned numer ous papers on the history of the Northwest, convinced the U.S. Post Office to rename several places newspaper publishers and writers. he said. “The country distinctly has a so as to reflect their history, and in- Though the ostensible purpose was past and a great many stirring things vited prominent historians, state gov- to study agricultural conditions, the happened many years before what we ernors, a former chief of staff of the group passed the Chief Joseph Battle- call our present civilization came here U.S. Army, and a U.S. Supreme Court field in Montana and spent time in at all.”3 This was Budd’s vision for the justice to give talks at various points Glacier National Park and Seaside, Upper Missouri Historical Expedition along the way. Oregon, giving Budd the opportunity that would go from St. Paul to Glacier These tours were the brainchild to point out numerous historic sites Park in July 1925, stopping at a wide of Great Northern president Ralph along the way.2 variety of historic sites along the way. Budd. An Iowa farm boy who received While Glacier and Seaside offered Budd’s objective, at least in part, his degree in civil engineering at the unforgettable scenery, Budd realized was to attract passengers to his rail- age of 19, Budd was a self- made intel- that many travelers thought the Great road. -

Proposed Action-Revised Forest Plan Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest

Helena – Lewis and Clark National Forest Draft Revised Forest Plan Appendix F. Evaluation of Wilderness Inventory Areas Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 Wilderness Evaluation Process Overview ........................................................................................1 Wilderness Inventory ............................................................................................................. 1 Public Comment to the Inventory ...................................................................................................2 Summary of Wilderness Recommendations for the Proposed Action....................................... 4 Evaluation of Inventoried Polygons ........................................................................................ 5 Big Belts Geographic Area ............................................................................................................. 11 Big Log Area (BB1) ............................................................................................................................................... 11 Hogback Area (BB2) ............................................................................................................................................ 17 Trout Creek Area (BB3) ....................................................................................................................................... 23 North Belts Area (BB4) .......................................................................................................................................