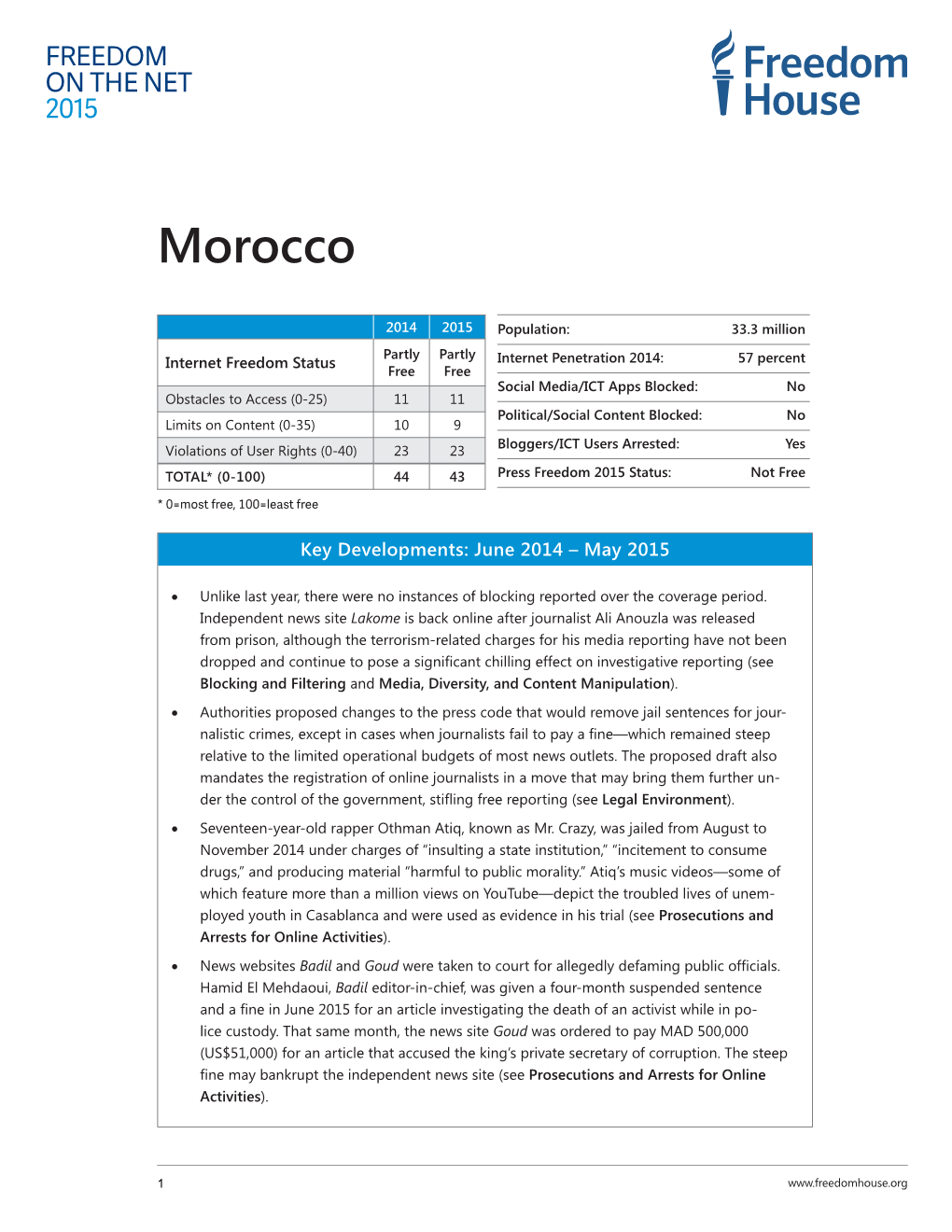

Freedom on the Net 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morocco: an Emerging Economic Force

Morocco: An Emerging Economic Force The kingdom is rapidly developing as a manufacturing export base, renewable energy hotspot and regional business hub OPPORTUNITIES SERIES NO.3 | DECEMBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 3 I. ECONOMIC FORECAST 4-10 1. An investment and export-led growth model 5-6 2. Industrial blueprint targets modernisation. 6-7 3. Reforms seek to attract foreign investment 7-9 3.1 Improvements to the business environment 8 3.2 Specific incentives 8 3.3 Infrastructure improvements 9 4. Limits to attractiveness 10 II. SECTOR OPPORTUNITIES 11-19 1. Export-orientated manufacturing 13-15 1.1 Established and emerging high-value-added industries 14 2. Renewable energy 15-16 3. Tourism 16-18 4. Logistics services 18-19 III. FOREIGN ECONOMIC RELATIONS 20-25 1. Africa strategy 20-23 1.1 Greater export opportunities on the continent 21 1.2 Securing raw material supplies 21-22 1.3 Facilitating trade between Africa and the rest of the world 22 1.4 Keeping Africa opportunities in perspective 22-23 2. China ties deepening 23-24 2.1 Potential influx of Chinese firms 23-24 2.2 Moroccan infrastructure to benefit 24 3 Qatar helping to mitigate reduction in gulf investment 24-25 IV. KEY RISKS 26-29 1. Social unrest and protest 26-28 1.1 2020 elections and risk of upsurge in protest 27-28 1.2 But risks should remain contained 28 2. Other important risks 29 2.1 Export demand disappoints 29 2.2 Exposure to bad loans in SSA 29 2.3 Upsurge in terrorism 29 SUMMARY Morocco will be a bright spot for investment in the MENA region over the next five years. -

S O N a S I D R a P P O R T a N N U

SONASID Rapport Annuel 2 0 1 0 [Rapport Annuel 2010] { S ommaire} 04 MESSAGE DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL 06 HISTORIQUE 07 PROFIL 09 CARNET DE L’ACTIONNAIRE 10 GOUVERNANCE 15 STRATÉGIE 19 ACTIVITÉ 25 RAPPORT SOCIAL 31 ÉLÉMENTS FINANCIERS 3 [Rapport Annuel 2010] Chers actionnaires, L’année 2010 a été particulièrement difficile pour l’ensemble Sonasid devrait en effet profiter d’un marché international des entreprises sidérurgiques au Maroc qui ont subi de favorable qui augure de bonnes perspectives avec la plein fouet à la fois les fluctuations d’un marché international prudence nécessaire, eu égard des événements récents Message du perturbé et la baisse locale des mises en chantier dans imprévisibles (Japon, monde arabe), mais une tendance { l’immobilier et le BTP. Une situation qui a entraîné une qui se confirme également sur le marché local qui devrait réduction de la consommation nationale du rond-à-béton bénéficier dès le second semestre 2011 de la relance des Directeur General qui est passée de 1500 kt en 2009 à 1400 kt en 2010. chantiers d’infrastructures et d’habitat social. } Un recul aggravé par la hausse des prix des matières premières, la ferraille notamment qui a représenté 70% du Nous sommes donc optimistes pour 2011 et mettrons prix de revient du rond-à-béton. Les grands consommateurs en œuvre toutes les mesures nécessaires pour y parvenir. d’acier sont responsables de cette inflation, la Chine en Nous avons déjà en 2010 effectué des progrès notables au particulier, au détriment de notre marché qui, mondialisé, a niveau de nos coûts de transformations, efforts que nous été directement affecté. -

Governance and Representation in the Afghan Urban Transition

Afghanistan’s Constitution Ten Years On: What Are the Issues? Mohammad Hashim Kamali August 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Issues Paper Afghanistan’s Constitution Ten Years On: What Are the Issues? Mohammad Hashim Kamali August 2014 Funding for this research was provided by the United States Institute of Peace and the Embassy of Finland. 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Cover photo: (From top to bottom): A view of the 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga Sessions; people’s representatives gesture during 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga; people’s representatives listening to a speech during 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga; Loya Jirga members during the 2004 Constitutional Loya Jirga, Kabul (by National Archives of Afghanistan). AREU wishes to thank the National Archives of Afghanistan for generously granting access to its photo collection from the 2004 Constitutional Loya Jirga. Layout: Ahmad Sear Alamyar AREU Publication Code: 1416E © 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of AREU. Some rights are reserved. This publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted only for non- commercial purposes and with written credit to AREU and the author. Where this publication is reproduced, stored or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Any use of this publication falling outside of these permissions requires prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be sought by emailing [email protected] or by calling +93 (0) 799 608 548. -

The Case of Morocco

Democracy Promotion in the European Neighbourhood Policy the case of Morocco Author: Helena Bergé Supervised by: Hubert Smekal, Ph.D. Masaryk University 2012-2013 ABSTRACT Contrary to European Union (EU) rhetoric on the importance of democracy promotion, security considerations have always been prioritised over democratisation in its relations with the Southern Mediterranean. In a review of the European Neighbourhood Policy after the Lisbon Treaty and the Arab Spring in 2011, the EU pleaded again to give full attention to democracy considerations. This research paper investigates whether democracy promotion in the ENP towards Morocco has undergone any change since the review of the policy, both in substance and importance. A comparative analysis of European democracy support before and after 2011 in Morocco based on policy reports, financial allocations and conditionality mechanisms reveals that socio- economic conditions are the main focus of EU democracy promotion in Morocco, while most changes can be found in an increased support of civil society. However, the EU seems to repeat its previous behaviour by again prioritising security over democratisation. II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AP: Action plan CAT: Convention against Torture CEDAW: Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women CFSP: Common Foreign and Security Policy CSF: Civil Society Facility CSO: Civil Society Organisation DCFTA: Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement EEAS: European External Action Service EED: European Endowment for Democracy EIDHR -

36687838.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank AVOIDING THE ARAB SPRING? THE POLITICS OF LEGITIMACY IN KING MOHAMMED VI’S MOROCCO by MARGARET J. ABNEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Margaret J. Abney Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Political Science by: Craig Parsons Chairperson Karrie Koesel Member Tuong Vu Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Margaret J. Abney iii THESIS ABSTRACT Margaret J. Abney Master of Arts Department of Political Science June 2013 Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco During the 2011 Arab Spring protests, the Presidents of Egypt and Tunisia lost their seats as a result of popular protests. While protests occurred in Morocco during the same time, King Mohammed VI maintained his throne. I argue that the Moroccan king was able to maintain his power because of factors that he has because he is a king. These benefits, including dual religious and political legitimacy, additional control over the military, and a political situation that make King Mohammed the center of the Moroccan political sphere, are not available to the region’s presidents. -

Jehovah's Witnesses

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: MAR32111 Country: Morocco Date: 27 August 2007 Keywords: Morocco – Christians – Catholics – Jehovah’s Witnesses – French language This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. What is the view of the Moroccan authorities to Catholicism and Christianity (generally)? Have there been incidents of mistreatment because of non-Muslim religious belief? 2. In what way has the attitude of the authorities to Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christians changed (if it has) from 1990 to 2007? 3. Is there any evidence of discrimination against non-French speakers? RESPONSE 1. What is the view of the Moroccan authorities to Catholicism and Christianity (generally)? Have there been incidents of mistreatment because of non-Muslim religious belief? Sources report that foreigners openly practice Christianity in Morocco while Moroccan Christian converts practice their faith in secret. Moroccan Christian converts face social ostracism and short periods of questioning or detention by the authorities. Proselytism is illegal in Morocco; however, voluntary conversion is legal. The information provided in response to these questions has been organised into the following two sections: • Foreign Christian Communities in Morocco; and • Moroccan Christians. -

MOROCCO COUNTRY REPORT (In French) ETAT DES LIEUX DE LA CULTURE ET DES ARTS

MOROCCO Country Report MOROCCO COUNTRY REPORT (in French) ETAT DES LIEUX DE LA CULTURE ET DES ARTS Decembre 2018 Par Dounia Benslimane (2018) This report has been produced with assistance of the European Union. The content of this report is the sole responsibility of the Technical Assistance Unit of the Med- Culture Programme. It reflects the opinion of contributing experts and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. 1- INTRODUCTION ET CONTEXTE Le Maroc est un pays d’Afrique du Nord de 33 848 242 millions d’habitants en 20141, dont 60,3% vivent en milieux urbain, avec un taux d’analphabétisme de 32,2% et 34,1% de jeunes (entre 15 et 34 ans), d’une superficie de 710 850 km2, indépendant depuis le 18 novembre 1956. Le Maroc est une monarchie constitutionnelle démocratique, parlementaire et sociale2. Les deux langues officielles du royaume sont l’arabe et le tamazight. L’islam est la religion de l’État (courant sunnite malékite). Sa dernière constitution a été réformée et adoptée par référendum le 1er juillet 2011, suite aux revendications populaires du Mouvement du 20 février 2011. Données économiques3 : PIB (2017) : 110,2 milliards de dollars Taux de croissance (2015) : +4,5% Classement IDH (2016) : 123ème sur 188 pays (+3 places depuis 2015) Le Maroc a le sixième PIB le plus important en Afrique en 20174 après le Nigéria, l’Afrique du Sud, l’Egypte, l’Algérie et le Soudan, selon le top 10 des pays les plus riches du continent établi par la Banque Africaine de Développement. -

MOROCCO Morocco Is a Monarchy with a Constitution, an Elected

MOROCCO Morocco is a monarchy with a constitution, an elected parliament, and a population of approximately 34 million. According to the constitution, ultimate authority rests with King Mohammed VI, who presides over the Council of Ministers and appoints or approves members of the government. The king may dismiss ministers, dissolve parliament, call for new elections, and rule by decree. In the bicameral legislature, the lower house may dissolve the government through a vote of no confidence. The 2007 multiparty parliamentary elections for the lower house went smoothly and were marked by transparency and professionalism. International observers judged that those elections were relatively free from government- sponsored irregularities. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. Citizens did not have the right to change the constitutional provisions establishing the country's monarchical form of government or those designating Islam the state religion. There were reports of torture and other abuses by various branches of the security forces. Prison conditions remained below international standards. Reports of arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detentions, and police and security force impunity continued. Politics, as well as corruption and inefficiency, influenced the judiciary, which was not fully independent. The government restricted press freedoms. Corruption was a serious problem in all branches of government. Child labor, particularly in the unregulated informal sector, and trafficking in persons remained problems. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed any politically motivated killings; however, there were reports of deaths in police custody. -

Returnees in the Maghreb: Comparing Policies on Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters in Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia

ͳͲ RETURNEES IN THE MAGHREB: COMPARING POLICIES ON RETURNING FOREIGN TERRORIST FIGHTERS IN EGYPT, MOROCCO AND TUNISIA THOMAS RENARD (editor) Foreword by Gilles de Kerchove and Christiane Höhn ʹͲͳͻ ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS Emna Ben Mustapha Ben Arab has a PhD in Culture Studies (University of La Manouba, Tunis/ University of California at Riverside, USA/Reading University, UK). She is currently a Non-resident Fellow at the Tunisian Institute for Strategic Studies (ITES), a member of the Mediterranean Discourse on Regional Security (George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies), and professor at the University of Sfax, Tunisia. Kathya Kenza Berrada is a Research Associate at the Arab Centre for Scientific Research and Humane Studies, Rabat, Morocco. Kathya holds a master’s degree in business from Grenoble Graduate Business School. Gilles de Kerchove is the EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator. Christiane Höhn is Principal Adviser to the EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator. Allison McManus is the Research Director at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. She holds an MA in global and international studies from University of California, Santa Barbara and a BA in international relations and French from Tufts University. Thomas Renard is Senior Research Fellow at the Egmont Institute, and Adjunct Professor at the Vesalius College. Sabina Wölkner is Head of the Team Agenda 2030 at the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) Berlin. Prior to this, Sabina was in charge of the Multinational Development Policy Dialogue of KAS Brussels until March 2019. From 2009-2014, she worked in Bosnia and Herzegovina and headed the foundation's country programme. Sabina joined KAS in 2006. -

Their Eyes on Me

Their Eyes On Me Stories of surveillance in Morocco Their Eyes on Me Photo © Anthony Drugeon 02 Their Eyes on Me Stories of surveillance in Morocco www.privacyinternational.org Their Eyes on Me Photo © Anthony Drugeon 04 Their Eyes on Me Table of Contents Foreword 07 Introduction 08 Hisham Almiraat 14 Samia Errazzouki 22 Yassir Kazar 28 Ali Anouzla 32 05 Their Eyes on Me Photo © Anthony Drugeon 06 Their Eyes on Me Foreword Privacy International is a charity dedicated to fighting for the right to privacy around the world. We investigate the secret world of government surveillance and expose the companies enabling it. We litigate to ensure that surveillance is consistent with the rule of law. We advocate for strong national, regional and international laws that protect privacy. We conduct research to catalyse policy change. We raise awareness about technologies and laws that place privacy at risk, to ensure that the public is informed and engaged. We are proud of our extensive work with our partners across the world. In particular, over the past year we have been working in 13 countries to assist local partner organisations in developing capacities to investigate surveillance and advocate for strong privacy protections in their country and across regions. Morocco is one of the key countries of focus, having met with activists dedicated to defending the internet and more specifically the inviolability of electronic communications. Hisham Almiraat – both a subject of surveillance and a passionate privacy advocate – has been at the forefront of this battle, with his new organisation, Association des Droits Numériques. -

Sustainability Index 2006/2007

MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2006/2007 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa www.irex.org/msi Copyright © 2008 by IREX IREX 2121 K Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 Fax: (202) 628-8189 www.irex.org Project manager: Leon Morse IREX Project and Editorial Support: Blake Saville, Mark Whitehouse, Christine Prince Copyeditors: Carolyn Feola de Rugamas, Carolyn.Ink; Kelly Kramer, WORDtoWORD Editorial Services Design and layout: OmniStudio Printer: Kirby Lithographic Company, Inc. Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute the MSI in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgement “The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) is a product of IREX with funding from USAID and the US State Department’s Middle East Partnership Initiative, and the Iraq study was produced with the support and funding of UNESCO.”; (b) the MSI is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of the MSI are made. Acknowledgment: This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Department of State’s Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No. #DFD-A-00-05-00243 (MSI-MENA) via a Task Order by the Academy for Educational Development. Additional support for the Iraq study was provided by UNESCO. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, MEPI, UNESCO, or IREX. -

Diapositive 1

SALON INTERNATIONAL DE LA FINANCE ETHIQUE ET PARTICIPATIVE Du 26 au 28 janvier 2017 REVUE DE PRESSE RAPPEL DES FAITS Le 1er Salon International de la Finance Ethique et Participative a été organisé du 26 au 28 janvier 2017 au Centre de Conférences de l’Office des Changes à Casablanca sous le thème générique ‘’Finance Ethique et Participative: Une contribution à la croissance et à l’inclusion économique au Maroc’’. C’est la première manifestation du genre à se tenir à l’échelle nationale et entièrement consacré à la finance participative. Le SIFEP a réuni les établissements bancaires et les institutions concernés par ce mode de financement aujourd’hui conquérant partout dans le monde arabo-musulman et qui perce même l’espace financier européen. Cette 1ère édition organisé par URBACOM- sous l’égide des ministères de l’Enseignement Supérieur, de la Recherche et de la Formation des cadres ainsi que de l’Habitat et de la Politique de la ville - avait un double objectif : Faire connaître au large public l’offre multiple de ce nouveau mode de financement, ses modalités et la champs de sa couverture et, en même temps, de donner l’occasion aux experts (chercheurs, techniciens du financement, enseignants, étudiants…) d’interroger tous les aspects théoriques et pratiques de la finance éthique et participative. Toute la presse nationale a été convié à la séance d’inauguration en présence de M. Abdelilah Benkiran, Chef du Gouvernement., d’autres ministres et de plusieurs personnalités, nationales et internationales, du domaine de la finance et de la