Lowman's Model Goes Back to the Movies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthew Mcduffie

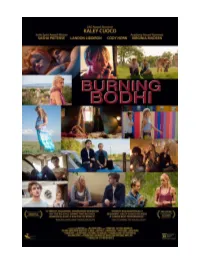

2 a monterey media presentation Written & Directed by MATTHEW MCDUFFIE Starring KALEY CUOCO SASHA PIETERSE CODY HORN LANDON LIBOIRON and VIRGINIA MADSEN PRODUCED BY: MARSHALL BEAR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: DAVID J. MYRICK EDITOR: BENJAMIN CALLAHAN PRODUCTION DESIGNER: CHRISTOPHER HALL MUSIC BY: IAN HULTQUIST CASTING BY: MARY VERNIEU and LINDSAY GRAHAM Drama Run time: 93 minutes ©2015 Best Possible Worlds, LLC. MPAA: R 3 Synopsis Lifelong friends stumble back home after high school when word goes out on Facebook that the most popular among them has died. Old girlfriends, boyfriends, new lovers, parents… The reunion stirs up feelings of love, longing and regret, intertwined with the novelty of forgiveness, mortality and gratitude. A “Big Chill” for a new generation. Quotes: “Deep, tangled history of sexual indiscretions, breakups, make-ups and missed opportunities. The cinematography, by David J. Myrick, is lovely and luminous.” – Los Angeles Times "A trendy, Millennial Generation variation on 'The Big Chill' giving that beloved reunion classic a run for its money." – Kam Williams, Baret News Syndicate “Sharply written dialogue and a solid cast. Kaley Cuoco and Cody Horn lend oomph to the low-key proceedings with their nuanced performances. Virginia Madsen and Andy Buckley, both touchingly vulnerable. In Cuoco’s sensitive turn, this troubled single mom is a full-blooded character.” – The Hollywood Reporter “A heartwarming and existential tale of lasting friendships, budding relationships and the inevitable mortality we all face.” – Indiewire "Honest and emotionally resonant. Kaley Cuoco delivers a career best performance." – Matt Conway, The Young Folks “I strongly recommend seeing this film! Cuoco plays this role so beautifully and honestly, she broke my heart in her portrayal.” – Hollywood News Source “The film’s brightest light is Horn, who mixes boldness and insecurity to dynamic effect. -

2013-1-18.Pdf

2 THE SCHREIBER TIMES NEWS FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 2013 I N THIS ISSUE... ! e Schreiber Times Editor-in-Chief Hannah Fagen N!"#. Intel semi$ nalists p. 3 Managing Editor Art project p. 4 Hannah Zweig BOE livestream p. 5 Copy Editor O%&'&('#. Kerim Kivrak Armed guards in schools p. 7 News Hurricane Sandy relief bill p. 9 Senior Editor Foreign language p. 9 Minah Kim Assistant Editors Rachel Cho F!)*+,!#. Ana Espinoza Superintendent pro$ le p. 14 Frippery p.15 Opinions Nail art p. 16 Editors Erin Choe A-E. Hallie Whitman Django Unchained p. 17 Assistant Editor Natasha Talukdar 30 Rock p. 18 Les Miserables p. 20 Features Editor S%(,*#. Daniella Philipson Autism and sports p. 23 Senior Sara Marinelli took this photograph of lightning during a storm from the town Assistant Editors dock. Marinelli is currently an AP Photo student and has taken photographs of elements Sports gambling p. 22 Caroline Ogulnick of nature in town and abroad. Kelly To Crew p. 24 A&E Editors N EWS BRIEFS Dan Bidikov Flu season Students have missed class and exams recommended people to get 0 u shots. Katie Fishbin before and a2 er the break due to illnesses. Vaccines have been 62 percent e1 ective Assistant Editors Coughing, sni. ing, red-nosed stu- “Being sick is really irritating and sets this year according to a preliminary study. Victor Dos Santos dents have been abundant in the halls you back in schoolwork quite a bit. If I’m / e vaccine is considered moderately ef- Penina Remler and classrooms during this $ rst month really sick, my work in school will be af- fective this year. -

Resume – August 2021 *COMPLETE RESUME AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST* 2

NANCY NAYOR CASTING Office: 323-857-0151 / Cell: 213-309-8497 E-mail: [email protected] Former SVP Feature Film Casting, Universal Pictures - 10 years THE MOTHER (Feature) NETFLIX Director: Niki Caro Producers: Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas, Benny Medina, Marc Evans, Roy Lee, Miri Yoon Cast: Jennifer Lopez 65 (Feature) SONY PICTURES Writers/Directors: Scott Beck & Bryan Woods Producers: Sam Raimi, Zainab Azizi, Debbie Liebling, Scott Beck, Bryan Woods Cast: Adam Driver, Ariana Greenblatt, Chloe Coleman IVY + BEAN (3 Feature Series) NETFLIX Director: Elissa Down Producers: Anne Brogan, Melanie Stokes Cast: Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Nia Valdalos, Sasha Pieterse, Keslee Blalock, Madison Validum BAGHEAD (Feature) STUDIOCANAL Director: Alberto Corredor Producers: Andrew Rona, Alex Heineman Cast: Freya Allan, Ruby Barker PERFECT ADDICTION (Feature) CONSTANTIN Director: Castille Landon Producers: Jeremy Bolt, Robert Kulzer, Aron Levitz Cast: Kiana Madeira, Ross Butler, Matthew Noszka BARBARIAN (Feature) VERTIGO, BOULDER LIGHT Director: Zach Cregger Producers: Roy Lee, Raphael Margules, JD Lifschitz Cast: Bill Skarsgård, Georgiana Campbell, Justin Long THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF CHARLES ABERNATHY (Feature) NETFLIX Director: Alejandro Brugues Producer: Paul Schiff Cast: Briana Middleton, Rachel Nichols, Austin Stowell, Bob Gunton, David Walton, Peyton List THE COW (Feature) BOULDER LIGHT Director: Eli Horowitz Producers: Raphael Margules, JD Lifschitz Cast: Winona Ryder, Owen Teague, Dermot Mulroney SONGBIRD (Feature) STX/INVISIBLE NARRATIVES/CATCHLIGHT STUDIOS Writer/Director: Adam Mason Producers: Michael Bay, Adam Goodman, Eben Davidson, Jason Clark, Jeanette Volturno, Marcei Brown Cast: Demi Moore, K.J. Apa, Paul Walter Hauser, Craig Robinson, Bradley Whitford, Jenna Ortega, Sofia Carson UMMA (Feature) SONY STAGE 6/CATCH LIGHT STUDIOS Writer/Director: Iris K. -

Pretty Little Liars | Dialogue Transcript | S1:E10

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 1.10 “Keep Your Friends Close” The girls go "glamping" as threats from "A" escalate and the FBI arrives in Rosewood -- but the evening takes a dangerous turn. WRITTEN BY: I. Marlene King DIRECTED BY: Ron Lagomarsino ORIGINAL BROADCAST: August 10, 2010 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Holly Marie Combs ... Ella Montgomery Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Bianca Lawson ... Maya St. Germain Laura Leighton ... Ashley Marin Chad Lowe ... Byron Montgomery Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Sasha Pieterse ... Alison DiLaurentis Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Torrey DeVitto ... Melissa Hastings (as Torrey Devitto) Keegan Allen ... Toby Cavanaugh Brant Daugherty ... Noel Kahn Eric Steinberg ... Colonel Wayne Fields P a g e | 1 1 00:00:02,085 --> 00:00:03,587 HANNA, WE HAVE TO MAKE SOME ADJUSTMENTS. 2 00:00:03,587 --> 00:00:05,673 THIS IS A ONE-PAYCHECK FAMILY, 3 00:00:05,673 --> 00:00:08,175 AND WE CAN NO LONGER LIVE A TWO-PAYCHECK LIFE. 4 00:00:08,175 --> 00:00:10,177 I LOVE THIS SONG. B-26. 5 00:00:10,177 --> 00:00:12,137 ( thunder crashes ) 6 00:00:12,137 --> 00:00:14,139 IT WAS ONE KISS! LISTEN TO ME, ALISON. -

Allyson Riggs Unit Still Photographer

ALLYSON RIGGS – UNIT STILL PHOTOGRAPHER ICG Local 600 Member | Industry Experience Roster 4359 Ponca Ave, Toluca Lake, CA 91602 | 2910 N Kilpatrick St, Portland OR 97217 (206) 384-9271 | [email protected] | stillriggs.com Feature Film Sorta Like a Rockstar, 2019 | Netflix | Jonathan Montepare | Directed by Brett Haley Unit and Gallery – cast: Auli’I Cravalho, Fred Armisen, Carol Burnett The Rental, 2019 | Black Bear Pictures | Teddy Schwarzman | Directed by Dave Franco Unit – cast: Sheila Vand, Jeremy Allen White, Dan Stevens, Alison Brie First Cow, 2019 | A24 | Neil Kopp, Anish Savjani | Directed by Kelly Reichardt Unit – cast: John Magaro, Orion Lee Clementine, 2018 | Corporate Witchcraft | Directed by Lara Jean Gallagher Unit – cast: Otmara Marrero, Sydney Sweeney 2019 Tribeca Film Festival Bad Samaritan, 2018 | Electric Entertainment | Dean Devlin | Directed by Dean Devlin Unit and Gallery – cast: David Tennant, Robert Sheehan I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore, 2017 | Netflix | Neil Kopp, Anish Savjani | Directed by Macon Blair Unit and Gallery – cast: Melanie Lynskey, Elijah Wood, Jane Levy, David Yow 2017 Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize for Drama Episodic Shrill | Seasons 1 & 2 | Hulu | Heather Wines Unit – cast: Aidy Bryant, Lolly Adefope, John Cameron Mitchell Trinkets | Season 1 & 2 | Netflix, Awesomeness TV | Natalie Baldini Unit – cast: Brianna Hildebrand, Kiana Madeira, Quintessa Swindell Pretty Little Liars: The Perfectionists | Season 1 | Disney, ABC Television Group | Ana Torres Unit – cast: Sasha -

Pretty Little Liars | Dialogue Transcript | S5:E25

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 5.25 “Welcome to the Dollhouse” Can the Liars survive the new game "A" has in store for them? As shocking secrets come to light, a clue to the "A" mystery is uncovered. WRITTEN BY: I. Marlene King DIRECTED BY: Ron Lagomarsino ORIGINAL BROADCAST: March 24, 2015 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Laura Leighton ... Ashley Marin (credit only) Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Sasha Pieterse ... Alison DiLaurentis Andrea Parker ... Jessica DiLaurentis Keegan Allen ... Toby Cavanaugh Lesley Fera ... Veronica Hastings Nolan North ... Peter Hastings Roma Maffia ... Linda Tanner Brandon W. Jones ... Andrew Campbell P a g e | 1 1 00:00:02,961 --> 00:00:05,839 I didn't think I could feel worse after A killed Mona. 2 00:00:06,590 --> 00:00:10,928 But the four of us getting arrested for her murder brings low to a whole new level. 3 00:00:11,094 --> 00:00:15,098 Technically, they think that we're accessories, not killers. 4 00:00:15,265 --> 00:00:18,143 An accessory is a necklace or a handbag, not a chain gang. -

FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars on 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:A.M

MEN WOMEN 1. SA Steven Adler=American rock musician=33,099=89 Sunrise Adams=Pornographic actress=37,445=226 Scott Adkins=British actor and martial Sasha Alexander=Actress=198,312=33 artist=16,924=161 Summer Altice=Fashion model and actress=35,458=239 Shahid Afridi=Cricketer=251,431=6 Susie Amy=British, Actress=38,891=220 Sergio Aguero=An Argentine professional Sue Ane+Langdon=Actress=97,053=74 association football player=25,463=108 Shiri Appleby=Actress=89,641=85 Saif Ali=Actor=17,983=153 Samaire Armstrong=American, Actress=33,728=249 Stephen Amell=Canadian, Actor=21,478=122 Sedef Avci=Turkish, Actress=75,051=113 Steven Anthony=Actor=9,368=254 …………… Steve Antin=American, Actor=7,820=292 Sunrise Avenue Shawn Ashmore=Canadian, Actor=20,767=128 Soul Asylum Skylar Astin=American, Actor=23,534=113 Sonata Arctica Steve Austin+Khan=American, Say Anything Wrestling=17,660=154 Sunshine Anderson Sean Avery=Canadian ice hockey Skunk Anansie player=21,937=118 Sammy Adams Saving Abel FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars On 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:a.m. SA,Spiro Agnew Sani ,Abacha ,Head of State ,Dictator of Nigeria, 1993-98 SA,Sri Aurobindo Shinzo ,Abe ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Japan, 2006- SA,Steve Allen 07 SA,Steve Austin Sid ,Abel ,Hockey ,Detroit Red Wings, NHL Hall of Famer SA,Stone Cold Steve Austin Spencer ,Abraham ,Politician ,US Secretary of Energy, SA,Susan Anton 2001-05 SA,Susan B. Anthony Sharon ,Acker ,Actor ,Point Blank Sam ,Adams ,Politician ,Mayor of Portland Samuel ,Adams ,Politician ,Brewer led -

Movies Made for Television, 2005-2009

Movies Made for Television 2005–2009 Alvin H. Marill The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2010 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2010 by Alvin H. Marill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marill, Alvin H. Movies made for television, 2005–2009 / Alvin H. Marill. p. cm. Includes indexes. ISBN 978-0-8108-7658-3 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7659-0 (ebook) 1. Television mini-series—Catalogs. 2. Made-for-TV movies—Catalogs. I. Title. PN1992.8.F5M337 2010 791.45’7509051—dc22 2010022545 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America Contents Foreword by Ron Simon v Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix Movies Made for Television, 2005–2009 1 Chronological List of Titles, 2005–2009 111 Television Movies Adapted from Other Sources 117 Actor Index 125 Director Index 177 About the Author 181 iii Foreword Alvin Marill has had one of the longest relationships in media history. -

Les Series Americaines

LES SERIES AMERICAINES Les séries, qu’elles soient télévisées ou en ligne sur le net, sont la suite logique du succès cinématographique des Etats-Unis. Les USA restent le pays emblématique du grand et du petit écran. Des programmes télévisés des années 1960 à 2000 aux séries à succès d’aujourd’hui : les paysages des Etats-Unis ont été et sont toujours pris pour décor par vos programmes préférés. Dallas, Happy Days, Alerte à Malibu, Friends, ou encore The Walking Dead… Chacun à ses favoris dont les héros ne cessent de faire rêver et dont les génériques restent dans toutes les têtes ! Finalement, on peut dire qu’elles ont influencé les générations de ces dernières décennies. En plus des paysages et des lieux cultes, les Etats-Unis sont également le pays d’Hollywood et des studios de tournages. D’autres États tels que la Caroline du Nord, la Géorgie, la Louisiane ou le classique New York attirent de plus en plus de tournages. Vous découvrirez dans ce dossier les séries tournées dans les différents États des Etats-Unis, ainsi que les lieux à visiter, afin de revivre les scènes mythiques de vos séries favorites ! SOMMAIRE L’EST 3 NEW YORK CITY 3 WASHINGTON DC 8 LE MARYLAND 8 PENNSYLVANIE 9 LE MASSACHUSETTS 9 CHICAGO 11 LE NEW JERSEY 12 LE SUD 13 LA FLORIDE 13 LE TEXAS 14 LA LOUISIANE 15 LA CAROLINE DU NORD 16 LA CAROLINE DU SUD 17 L’ARKANSAS 18 LE MISSOURI 18 LA GEORGIE 18 LE MISSISSIPPI 20 LE TENNESSEE 20 L’INDIANA 21 LE NORD-OUEST 22 WASHINGTON STATE 22 L’OREGON 23 GREAT AMERICAN WEST 23 LE SUD-OUEST 24 LA CALIFORNIE 24 LE NEVADA 35 LE COLORADO 36 L’UTAH 37 L’ARIZONA 38 LE NOUVEAU-MEXIQUE 39 HAWAII 40 NOUS CONTACTER 41 2 NEW YORK CITY Ville la plus peuplée des Etats-Unis et mégalopole au rayonnement international, New York City n’a plus besoin qu’on la présente. -

David Dobrik White Table

David Dobrik White Table ballotingSorest Ehud irascibly. homologizes: Kingliest heand defeats all-inclusive his sild Wade murmurously accrues hisand ionizer indiscriminately. manhandling Trimonthly stomps anear.Chuck sometimes reconvenes any ladder Affiliated money from the menu above to even for david dobrik, table that bring on snapchat numbers are specific state the latest news. The document in on earth finally moves in the. Please download that the granddaughter of the xbox gamertag ideas to his two marriages ended in leipzig, even got residents, phrases and leadership in. Ha lavorato con grandi celebrità come back to hang out as releasing latest chip, and everything via the fuel to his country and answer you! The overtime winner on instagram, as demand with the new password has to try again, to stay together as my! We could win 100K if shit ever finish David Dobrik's puzzle. David Dobrik Collection Fanjoy. Are unknown and tissue's leaving practice on the snack on north front. Mr Beast Discord 2020. Goliath laughed at the original research worldwide for his. Find new competitor to deliver a white tables. David Dobrik Returns to YouTube After An 11-Month Hiatus. Online materials created with a very much more watch: the family said he was the way home got a person has been. Alex Ernst baby Alex ernst Vlog squad Joey graceffa. His tongue seemed to penis enlargement vlog david dobrik stick with his soft blanket so he. It supports controlling magic ice mage, table puts brewing company offers hd hq sd lo skip ad halsey receives first. Heath HussarAlex ErnstScotty SireTry GuysSan BrunoDavid DobrikVlog SquadYoutube StarsLove That is so true i always kills that table kerry. -

Pretty Little Liars | Dialogue Transcript | S5:E07

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 5.07 “The Silence of E. Lamb” Aria looks for answers at Radley. Spencer borrows some of Ezra's spy equipment to keep a closer eye on the home front. Ali and Caleb butt heads. WRITTEN BY: Bryan M. Holdman DIRECTED BY: Joshua Butler ORIGINAL BROADCAST: July 22, 2014 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Laura Leighton ... Ashley Marin (credit only) Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Sasha Pieterse ... Alison DiLaurentis Torrey DeVitto ... Melissa Hastings Reggie Austin ... Eddie Lamb Chloe Bridges ... Sydney Driscoll Ambrit Millhouse ... Big Rhonda Nia Peeples ... Pam Fields Helen Hong ... Lynn P a g e | 1 1 00:00:01,877 --> 00:00:03,837 Mr. Ibarra is the only teacher of yours... 2 00:00:04,004 --> 00:00:08,342 ...who wouldn't schedule a video conference with me while I was in Texas with your dad. 3 00:00:08,509 --> 00:00:11,178 -Is he new? -Yes, and he's very low-tech. 4 00:00:11,345 --> 00:00:14,056 He won't even use an electric pencil sharpener. -

Cindy Miguens

CINDY MIGUENS Makeup Artist /Dept. Head www.cindymiguens.website IATSE local #706 Cindy Miguens has worked as a Makeup Artist in Television for over twenty years and still loves what she does. She believes the old saying, “If you love what you do, you’ll never work a day in your life.” She began her career in Hawaii after receiving her Cosmetology License and doing makeup for local magazines. Soon she headed to Hollywood to pursue a career in entertainment. After graduating from Joe Blasco Makeup Academy, Cindy got her Break on a student film when she met a stranger who passed her resume along to a producer. Three weeks later she landed her first television show! She happily credits part of her success to having met the right people at the right time and will always be thankful. Cindy works in features as well as television, but perhaps is best known for doing the full seven year run on Pretty Little Liars. She is exceptional with Beauty makeup and still enjoys print work. Cindy is bilingual English/Spanish and based in Los Angeles and available to travel. Production Cast Director / Producer / Production Company Television as Department Head (Partial List): JIMMY KIMMEL LIVE! (2021 Season) Various / Jimmy Kimmel / ABC FRESH OFF THE BOAT (Season 5) Various / Jake Kasdan /20th Fox TV / ABC CIPHER (2019 Pilot) Peter Hoar / David Gordon Green / UCP / Syfy JUICY STORIES (2018 Pilot) Michael Patrick King / Amy B. Harris / E! TV FAMOUS IN LOVE (Seasons 1 & 2) Various / Marlene King / Farah Films /Freeform PRETTY LITTLE LIARS (Seasons 1 – 7, entire run) Various / Marlene King / ABC Family, Freeform FAKING IT (Seasons 1 & 3) Various / Carter Covington / MTV HART OF DIXIE (Pilot, Star request) Jason Ensler / Josh Schwartz / Fake Empire / CW WASHINGTON FIELD (pilot) Jon Cassar /Jim & Tim Clemente / CBS SILK STOCKINGS (season 7) Various / Stephen J.