DOCUMENT RESUME ED 378 106 SO 024 635 AUTHOR Weaver, Molly A. TITLE a Survey of Modes of Student Response Indicative of Musical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perry Como Lightly Latin Mp3, Flac, Wma

Perry Como Lightly Latin mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Latin / Pop Album: Lightly Latin Country: Germany Released: 1966 Style: Vocal, Easy Listening, Bossa Nova MP3 version RAR size: 1315 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1163 mb WMA version RAR size: 1543 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 644 Other Formats: MPC AUD MP4 APE VOC MIDI AAC Tracklist Hide Credits How Insensitive (Insensatez) A1 3:10 Written-By – Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius De Moraes Stay With Me A2 3:03 Written-By – Nick Perito, Ray Charles The Shadow Of Your Smile A3 3:46 Arranged By – Torrie ZitoWritten-By – Johnny Mandel, Paul Francis Webster Meditation (Meditaçao) A4 Backing Vocals – The Ray Charles SingersWritten-By – Antonio Carlos Jobim, Newton 3:45 Mendonça, Norman Gimbel And Roses And Roses A5 3:07 Backing Vocals – The Ray Charles SingersWritten-By – Dorival Caymmi, Ray Gilbert Yesterday A6 2:59 Written-By – Lennon-McCartney Coo Coo Roo Coo Coo Paloma B1 Backing Vocals – The Ray Charles SingersWritten-By – Patricia P. Valando, Ronnie Carson, 2:49 Tomas Mendez Dindi B2 4:16 Written-By – Aloysio De Oliveira, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Ray Gilbert Baía B3 Arranged By – Torrie ZitoBacking Vocals – The Ray Charles SingersWritten-By – Ary 3:25 Barroso, Ray Gilbert Once I Loved (Amor e Paz) B4 3:50 Written-By – Antonio Carlos Jobim, Ray Gilbert, Vinicius De Moraes Manhã De Carnaval B5 2:39 Backing Vocals – The Ray Charles SingersWritten-By – Antônio Maria, Luiz Bonfá Quiet Nights Of Quiet Stars B6 3:19 Written-By – Antonio Carlos Jobim, Buddy Kaye, Gene Lees Credits -

Collated Scripts

YOU WERE NEVER REALLY HERE. Screenplay by Lynne Ramsay Based on the novella by Jonathan Ames GOLDENROD REVISIONS: 8.29.16 GREEN REVISIONS: 8.24.16 YELLOW REVISIONS: 8.17.16 PINK REVISIONS: 8.5.16 BLUE REVISIONS: 7.25.16 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT: 7.14.16 1 INT. TITLES SEQUENCE 1 Close-up: An adult man’s mouth under water (Joe). He gulps in water. E.C.U: A CLEAR PLASTIC BAG, filled with air, stretched smooth. The inside surface mists - droplets of moisture form - break into miniature rivulets... O.S. The whisper of a BOY’S VOICE (Young Joe) counting down - ‘...1001, 1000, 999, 998, 997...’ With a sharp inhale the clear plastic inverts. The face of A MAN (Joe) as the bag is suddenly sucked hard onto his skin, distorting his features into an inhuman mask. O.S. The boy’s counting suspends. The faint beat of a pulse rises to replace it. The man exhales. The bag balloons again, clouding with his breath. The man breathes again, slowly, the plastic bag balloons and inverts. O.S. The boy’s monotone whisper resumes - ‘...996, 995, 994...’ The man never blinks beneath the plastic, eyes unseeing, its rise and fall around his mouth and nose the only sign of life. TITLES END. 2 INT. HOTEL ROOM, CINCINNATI - NIGHT 2 A GIRL’S FACE, filling the frame - a passport style photograph... ...16-years-old, smiling, a hint of lip gloss and eye shadow, lightly Latin features. The image appears to dance and flicker with an inner light. Slowly at first the picture darkens, then rapidly distorts and blackens. -

Ľ©É‡Œâ·Ç§'Èž« Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ' & Æ

佩里·科莫 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Just Out of Reach https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/just-out-of-reach-6316284/songs The Songs I Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-songs-i-love-7765273/songs 40 Greatest Hits https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/40-greatest-hits-4637400/songs It's Impossible https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/it%27s-impossible-16997432/songs Look to Your Heart https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/look-to-your-heart-17035278/songs We Get Letters https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/we-get-letters-7977561/songs I Think of You https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/i-think-of-you-5979185/songs Como Swings https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/como-swings-5155142/songs For the Young at Heart https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/for-the-young-at-heart-5467159/songs Sing to Me Mr. C https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sing-to-me-mr.-c-7522782/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/season%27s-greetings-from-perry-como- Season's Greetings from Perry Como 7441866/songs Saturday Night with Mr. C https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/saturday-night-with-mr.-c-7426736/songs By Request https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/by-request-5003818/songs So Smooth https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/so-smooth-7549513/songs And I Love You So https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/and-i-love-you-so-4753312/songs Today https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/today-7812181/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/when-you-come-to-the-end-of-the-day- -

From Conformity to Protest: the Evolution of Latinos in American Popular Culture, 1930S-1980S

From Conformity to Protest: The Evolution of Latinos in American Popular Culture, 1930s-1980s A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2017 by Vanessa de los Reyes M.A., Miami University, 2008 B.A., Northern Kentucky University, 2006 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Porter, Ph.D. Abstract “From Conformity to Protest” examines the visual representations of Latinos in American popular culture—specifically in film, television, and advertising—from the 1930s through the early 1980s. It follows the changing portrayals of Latinos in popular culture and how they reflected the larger societal phenomena of conformity, the battle for civil rights and inclusion, and the debate over identity politics and cultural authenticity. It also explores how these images affected Latinos’ sense of identity, particularly racial and ethnic identities, and their sense of belonging in American society. This dissertation traces the evolution of Latinos in popular culture through the various cultural anxieties in the United States in the middle half of the twentieth century, including immigration, citizenship, and civil rights. Those tensions profoundly transformed the politics and social dynamics of American society and affected how Americans thought of and reacted to Latinos and how Latinos thought of themselves. This work begins in the 1930s when Latin Americans largely accepted portrayals of themselves as cultural stereotypes, but longed for inclusion as “white” Americans. The narrative of conformity continues through the 1950s as the middle chapters thematically and chronologically examine how mainstream cultural producers portrayed different Latino groups—including Chicanos (or Mexican Americans), Puerto Ricans, and Cubans. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 2800-3399

RCA Discography Part 10 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 2800-3399 LPM/LSP 2800 – Country Piano-City Strings – Floyd Cramer [1964] Heartless Heart/Bonaparte's Retreat/Streets Of Laredo/It Makes No Difference Now/Chattanoogie Shoe Shine Boy/You Don't Know Me/Making Believe/I Love You Because/Night Train To Memphis/I Can't Stop Loving You/Cotton Fields/Lonesome Whistle LPM/LSP 2801 – Irish Songs Country Style – Hank Locklin [1964] The Old Bog Road/Too-Ra-Loo-Ra- Loo-Ral (That's An Irish Lullaby)/Danny Dear/If We Only Had Ireland Over Here/I'll Take You Home Again Kathleen/My Wild Irish Rose/Danny Boy/When Irish Eyes Are Smiling/A Little Bit Of Heaven/Galway Bay/Kevin Barry/Forty Shades Of Green LPM 2802 LPM 2803 LPM/LSP 2804 - Encore – John Gary [1964] Tender Is The Night/Anywhere I Wander/Melodie D'amour (Melody Of Love)/And This Is My Beloved/Ol' Man River/Stella By Starlight/Take Me In Your Arms/Far Away Places/A Beautiful Thing/If/(It's Been) Grand Knowing You/Stranger In Paradise LPM/LSP 2805 – On the Country-Side – Norman Luboff Choir [1964] Detroit City/Jambalaya (On The Bayou)/I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry/Your Cheatin’ Heart/You’re The Only Star (In My Blue Heaven)/Tennessee Waltz/I Can’t Stop Loving You/It Makes No Difference Now/Words/Four Walls/Anytime/You Are My Sunshine LPM/LSP 2806 – Dick Schory on Tour – Dick Schory [1964] Baby Elephant Walk/William Told/The Wanderin’ Fifer/Charade/Sing, Sing, Sing/St. -

Pittsburgh Vinyl Records

Use Command F (⌘F) or CTRL + F to search this document Call Number Composer / Group /Artist Conductor / Title Contents Format Album Year Director and/or Notes Info r RECORD AL 16043 8th Street Rox Live from the corner of rock 12” LP Decade 1987 & roll (stereo) Disc DDR- 3000 r RECORD AL 16042 ACDA Eastern Division Mack, Gerald ACDA Eastern Division recorded at 12” LP Mark MC- 1978 Honors Choir Honors Choir Wm. Penn (stereo) 9176 Hotel, Pgh., February 25, 1978 r RECORD AL 13869 Adams-Michaels Band WDVE Pittsburgh rocks analog, 33 Nova BMC- 1980 album 1/3 rpm, 80102 stereo. ; 12 in. r RECORD AL 16037 Affordable Floors, The Pittsburgh Sound Tracks 12" LP Itzy [198-?] (stereo) Records NR16371 (r) RECORD AL 15963 Alcoa Singers Glockner, An old-fashioned Christmas analog, 33 Aluminum 1979 Eleanor 1/3 rpm, Company stereo.; 12 of America in. 44-4184-J r RECORD AL 15973 All-City Senior High Schools Levin, Stanley 1965 Spring Music Festival Recorded May analog, 33 Century 1965 Orchestra of the Pittsburgh H. concert 13, 1965, in 1/3 rpm ; 12 Records Public Schools Carnegie Music in. 22274 Hall. r RECORD AL 16442 All-City Senior High Schools Levin, Stanley 1963 Spring Music Festival Recorded May analog, 33 Century 1963 Orchestra of the Pittsburgh H. concert 16, 1963, in 1/3 rpm ; 12 Records Public Schools ; Bell-Aires Carnegie Music in. 17141 Hall. r RECORD AL 16454 Allderdice Concert Band Annual spring concert 12" LP Engle [1970?] stereo Associates Recording r RECORD AL 15906 Allderdice High School DiPasquale, 1971 spring concert analog, 33 Conducto [1971] Concert Band Henry J. -

Rick L. Pope Phonograph Record Collection 10 Soundtrack/WB/Record

1 Rick L. Pope Phonograph Record Collection 10 soundtrack/WB/record/archives 12 Songs of Christmas, Crosby, Sinatra, Waring/ Reprise/record/archives 15 Hits of Jimmie Rodgers/Dot / record/archives 15 Hits of Pat Boone/ Dot/ record/archives 24 Karat Gold From the Sound Stage , A Double Dozen of All Time Hits from the Movies/ MGM/ record/archives 42nd Street soundtrack/ RCA/ record/archives 50 Years of Film (1923-1973)/WB/ record set (3 records and 1 book)/archives 50 Years of Music (1923-1973)/WB/ record set (3 records and 1 book)/archives 60 years of Music America Likes Best vols 1-3/RCA Victor / record set (5 pieces collectively)/archives 60 Years of Music America Likes Best Vol.3 red seal/ RCA Victor/ record/archives 1776 soundtrack / Columbia/ record/archives 2001 A Space Oddyssey sound track/ MGM/ record/archives 2001 A Space Oddyssey sound track vol. 2 / MCA/ record/archives A Bing Crosby Christmas for Today’s Army/NA/ record set (2 pieces)/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 1/ Columbia/record/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 2/ Columbia/record/archives A Bing Crosby Collection vol. 3/ Columbia/record/archives A Bridge Too Far soundtrack/ United Artists/record/archives A Collector’s Porgy and Bess/ RCA/ record/archives A Collector’s Showboat/ RCA/ record/archives A Christmas Sing with Bing, Around the World/Decca/record/archives A Christmas Sing with Bing, Around the World/MCA/record/archives A Chorus Line soundtrack/ Columbia/ record/ archives 2 A Golden Encore/ Columbia/ record/archives A Legendary Performer Series ( -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3400-3699

RCA Discography Part 11 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3400-3699 LPM/LSP 3400 - Remember – Norman Luboff Choir [1965] Remember/I'll Get By (As Long As I Have You)/Always/Dream/It Had To Be You/I'll Be Seeing You/Look To Your Heart/As Time Goes By/Day By Day/Together/The Very Thought Of You/I'll See You Again LPM/LSP 3401 - Shut the Door! (They’re Comin’ Through the Window!) – Buffalo Bills [1965] Shut The Door! (They're Comin' Through The Window)/I'm A Ding Dong Daddy/Sam, You Made The Pants Too Long (Lawd You Made The Night Too Long)/Josephine, Please No Lean On The Bell/Mad Dogs And Englishmen/Barney Google/Cigareetes, Whusky, And Wild Women/I Love A Piano/The Preacher And The Bear/Does The Spearmint Lose Its Flavor (On The Bedpost Over Night?)/Don't Bring Lulu/Too Fat Polka LPM/LSP 3402 - The Great Race (Stk) – Henry Mancini [1965] Overture/Push The Button, Max!/The Royal Waltz/Night Night Sweet Prince/They're Off/The Sweetheart Tree/The Great Race March/HeShould n't-A, Hadn't-A, Oughtn't-A Swang On Me!/Music To Become King By/Cold Finger/Pie-In-The-Face Polka LPM/LSP 3403 - Curtain Time – Paul Lavalle and the Band of America [1965] Overture From "The Sound Of Music”/Overture From "Do I Hear A Waltz”/Overture From "Hello Dolly”/Overture From "My Fair Lady”/Overture From "Camelot”/Overture From "Fiddler On The Roof” LPM/LSP 3404 - Tommy Leonetti Sings the Winners – Tommy Leonetti [1965] Spanish Harlem/So Much In Love/The Wayward Wind/Looking Back/Save The Last Dance For Me/(You've Got) Personality/Wonderful! Wonderful!/Moments To Remember/Come Softly To Me/Our Day Will Come/I Can't Stop Loving You/Oh Lonesome Me LPM/LSP 3405 - Class of ’65 – Floyd Cramer [1965] I Feel Fine/You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'/King Of The Road/Willow Weep For Me/I'll Follow The Sun/Downtown/Try To Remember/Cast Your Fate To The Wind/Dear Heart/I'll Be There/Mr. -

A&M Records Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0779q1nw No online items Finding Aid for the A&M Records records PASC-M.0269 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff, 2008. Finding aid revised by Melissa Haley, 2017. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2019 August 5. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the A&M Records PASC-M.0269 1 records PASC-M.0269 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: A&M Records records Creator: A & M Records (Firm) Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0269 Physical Description: 98 Linear Feet(196 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1959-2001 Abstract: The collection consists of sound recordings, manuscript musical arrangements, photographs, correspondence, promotional materials, posters, gold albums, awards, books, and ephemera from just prior to the founding of A & M Records in 1962 to a few years after its sale to Polygram in 1989, while Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert were still affiliated with the label. Portions of the collection stored off-site. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of collection unprocessed and currently undescribed. Please contact Special Collections reference ([email protected]) for more information. -

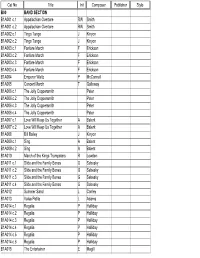

CEC Music Lib Instr 06.Fp5

Cat No Title Init Composer Publisher Style B00 BAND SECTION B1A001 c.1 Appalachian Overture RW Smith B1A001 c.2 Appalachian Overture RW Smith B1A002 c.1 Tingo Tango J Kinyon B1A002 c.2 Tingo Tango J Kinyon B1A003 c.1 Fanfare March F Erickson B1A003 c.2 Fanfare March F Erickson B1A003 c.3 Fanfare March F Erickson B1A003 c.4 Fanfare March F Erickson B1A004 Emperor Waltz P McConnell B1A005 Concert March T Galloway B1A006 c.1 The Jolly Coppersmith Peter B1A006 c.2 The Jolly Coppersmith Peter B1A006 c.3 The Jolly Coppersmith Peter B1A006 c.4 The Jolly Coppersmith Peter B1A007 c.1 Love Will Keep Us Together A Balent B1A007 c.2 Love Will Keep Us Together A Balent B1A008 Bill Bailey J Kinyon B1A009 c.1 Sing A Balent B1A009 c.2 Sing A Balent B1A010 March of the Kings Trumpeters R Lowden B1A011 c.1 Slide and the Family Bones G Sebesky B1A011 c.2 Slide and the Family Bones G Sebesky B1A011 c.3 Slide and the Family Bones G Sebesky B1A011 c.4 Slide and the Family Bones G Sebesky B1A012 Summer Sand L Conley B1A013 Valse Petite L Adams B1A014 c.1 Regalia P Halliday B1A014 c.2 Regalia P Halliday B1A014 c.3 Regalia P Halliday B1A014 c.4 Regalia P Halliday B1A014 c.5 Regalia P Halliday B1A014 c.6 Regalia P Halliday B1A015 The Entertainer E Magill Cat No Title Init Composer Publisher Style B1A016 c.1 You'll Never Walk Alone J O'Reilly B1A016 c.2 You'll Never Walk Alone J O'Reilly B1A017 c.1 Sounds of Sousa J Ployhar B1A017 c.2 Sounds of Sousa J Ployhar B1A018 Getting' It Together C Giovanni B1A019 Turn! Turn! Turn! F Coffield B1A020 A Brahms Symphonette -

RCA Victor Consolidated Series

RCA Discography Part 17 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor Consolidated Series In 1972, RCA instituted a consolidated series, where all RCA releases were in the same series, including albums that were released on labels distributed by RCA. APL 1 0001/APD 1 0001 Quad/APT 1 0001 Quad tape — Love Theme From The Godfather — Hugo Montenegro [1972] Medley: Baby Elephant Walk, Moon River/Norwegian Wood/Air on the G String/Quadimondo/I Feel the Earth Move/The Godfather Waltz/Love Theme from the Godfather/Pavanne/Stutterolgy RCA Canada KPL 1 0002 — Trendsetter — George Hamilton IV [1975] Canadian LP. Bad News/The Ways Of A Country Girl/Let My Love Shine/Where Would I Be Now/The Good Side Of Tomorrow/My Canadian Maid/The Wrong Side Of Her Door/Time's Run Out On You/The Isle Of St. Jean/The Dutchman RCA Red Seal ARL 1 0002/ARD 1 0002 Quad – The Fantastic Philadelphians Volume 1 – Eugene Ormandy and Philadelphia Orchestra [1972] EspanÞa Rhapsody (Chabrier)/The Sorcerer's Apprentice (Dukas)//Danse Macabre (Saint-Sae8ns)/A Night On Bald Mountain (Moussorgsky) 0003-0007 (no information) RCA Special Products DPL 1 0008 – Toyota Jazz Parade – Various Artists [1973] Theme from Toyota – Al Hirt/Java – Al Hirt/Cotton Candy – Al Hirt/When the Saints Go Marching In – Al Hirt/At the Jazz Band Ball – Dukes of Dixieland/St. Louis Blues – Louis Armstrong/St. James Infirmary – King Oliver//Hi-Heel Sneakers – Jose Feliciano/Amos Moses – Jerry Reed/Theme from Shaft – Generation Gap/Laughing – Guess Who/Somebody to Love – Jefferson Airplane 0009-0012 (no information) APL 1 0013/APD 1 0013 Quad/APT 1 0013 Quad tape — Mancini Salutes Sousa — Henry Mancini [1972] Drum Corps/Semper Fidelis/Washington Post/Drum Corps/King Cotton/National Fencibles/The Thunderer/Drum Corps/El Capitan/The U. -

45 Inventory

45 Inventory item type artist title condition price quantity 45RPM ? And the Mysterians 96 Tears / Midnight Hour VG+ 8.95 222 45RPM ? And the Mysterians I Need Somebody / "8" Teen vg++ 18.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Cryin' Time / I've Got A Tiger By The Tail vg+ 19.95 111 45RPM ? And the Mysterians Everyday I have to cry / Ain't Got No Home VG+ 8.95 111 Don't Squeeze Me Like Toothpaste / People In 10 C.C. 45 RPM Love VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. How Dare You / I'm Mandy Fly Me VG+ 12.95 111 45 RPM 10 C.C. Ravel's Bolero / Long Version VG+ 28.95 111 45 RPM 100% Whole Wheat Queen Of The Pizza Parlour / She's No Fool VG+ 12 111 EP:45RP Going To The River / Goin Home / Every Night 101 Strings MMM About / Please Don't Leave VG+ 56 111 101 Strings Orchestra Love At First Sight (Je T'Aime..Moi Nom Plus) 45 RPM VG+ 45.95 111 45RPM 95 South Whoot (There It Is) VG+ 26 111 A Flock of Seagulls Committed / Wishing ( If I had a photograph of you 45RPM nm 16 111 45RPM A Flock of Seagulls Mr. Wonderful / Crazy in the Heart nm 32.95 111 A.Noto / Bob Henderson A Thrill / Inst. Sax Solo A Thrill 45RPM VG+ 12.95 555 45RPM Abba Rock Me / Fernando VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abba Voulez-Vous / Same VG+ 16 111 PictureSle Abba Take A Chance On Me / I'M A Marionette eve45 VG+ 16 111 45RPM Abbot,Gregory Wait Until Tomorrow / Shake You Down VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM Abc When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 12.95 111 45RPM ABC When Smokey Sings / Be Near Me VG+ 8.95 111 45RPM ABC Reconsider Me / Harper Valley p.t.a.