The Rohtak Distlict Which Forms a Part of Haryana Is Strategically Situated in the Passage from the North-West Through the Delhi Gateway to the Broad Ganga Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

List of Villages for Special IMI.Pdf

GRAM SWARAJ ABHIYAN (14th April to 5th May, 2018) Sabka Sath Sabka Gaon Sabka Vikas Villages for Saturation of Seven Programmes State District Sub-District Sub-District Village Total State Name District Name Village Name No. of HH Code Code Code Name Code Population 06 Haryana 069 Panchkula 00356 Kalka 056980 Basawal (125) 247 1364 06 Haryana 069 Panchkula 00357 Panchkula 057159 Nawagaon Urf 214 1097 Khader (24) 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00358 Naraingarh 057193 Behloli (48) 231 1253 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00358 Naraingarh 057239 Bilaspur (258) 313 1510 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00358 Naraingarh 057244 Kherki Manakpur 229 1167 (256) 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00358 Naraingarh 057287 Panjlasa (Part)(96) 654 3203 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057346 Khatoli (30) 312 1649 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057367 Sarangpur (117) 377 1761 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057378 Ghasitpur (126) 216 1323 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057386 Rattanheri (22) 267 1519 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057389 Sapehra (66) 409 2127 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057394 Manglai (129) 377 2203 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00359 Ambala 057489 Addu Majra (278) 229 1216 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057523 Dubli (222) 218 1173 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057525 Chudiala (191) 297 1691 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057533 Nagla (196) 263 1380 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057540 Behta (158) 1500 7865 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057552 Tobha (20) 396 2251 06 Haryana 070 Ambala 00360 Barara 057565 Jharu Majra (77) 201 1048 06 Haryana -

Government of India Ground Water Year Book of Haryana State (2015

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE (2015-2016) North Western Region Chandigarh) September 2016 1 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE 2015-2016 Principal Contributors GROUND WATER DYNAMICS: M. L. Angurala, Scientist- ‘D’ GROUND WATER QUALITY Balinder. P. Singh, Scientist- ‘D’ North Western Region Chandigarh September 2016 2 FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board has been monitoring ground water levels and ground water quality of the country since 1968 to depict the spatial and temporal variation of ground water regime. The changes in water levels and quality are result of the development pattern of the ground water resources for irrigation and drinking water needs. Analyses of water level fluctuations are aimed at observing seasonal, annual and decadal variations. Therefore, the accurate monitoring of the ground water levels and its quality both in time and space are the main pre-requisites for assessment, scientific development and planning of this vital resource. Central Ground Water Board, North Western Region, Chandigarh has established Ground Water Observation Wells (GWOW) in Haryana State for monitoring the water levels. As on 31.03.2015, there were 964 Ground Water Observation Wells which included 481 dug wells and 488 piezometers for monitoring phreatic and deeper aquifers. In order to strengthen the ground water monitoring mechanism for better insight into ground water development scenario, additional ground water observation wells were established and integrated with ground water monitoring database. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

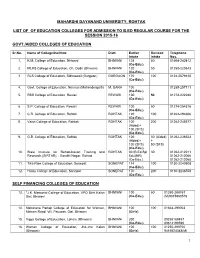

List of Education Colleges B.Ed Regular Course

MAHARSHI DAYANAND UNIVERSITY, ROHTAK LIST OF OF EDUCATION COLLEGES FOR ADMISSION TO B.ED REGULAR COURSE FOR THE SESSION 2015-16 GOVT./AIDED COLLEGES OF EDUCATION Sr.No. Name of College/Institute Distt. Earlier Revised Telephone Intake Intake Nos. 1. K.M. College of Education, Bhiwani BHIWANI 128 50 01664-242412 (Co-Edu.) 2. MLRS College of Education, Ch. Dadri (Bhiwani) BHIWANI 120 50 01250-220843 (Co-Edu.) 3. RLS College of Education, Sidhrawali (Gurgaon) GURGAON 170 100 0124-2679128 (Co-Edu.) 4. Govt. College of Education, Narnaul (Mahendergarh) M. GARH 100 01285-257111 (Co-Edu.) 5. RBS College of Education, Rewari REWARI 100 50 01274-222280 (Co-Edu.) 6. S.P. College of Education, Rewari REWARI 100 50 01274-254316 (Co-Edu.) 7. C.R. College of Education, Rohtak ROHTAK 120 100 01262-294606 (Co-Edu.) 8. Vaish College of Education, Rohtak ROHTAK 100 200 01262-248577 (Aided)+ 100 (SFS) (Co-Edu.) 9. G.B. College of Education, Rohtak ROHTAK 100 50 (Aided) 01262-236523 (Aided)+ + 100 (SFS) 50 (SFS) (Co-Edu.) 10. State Institute for Rehabilitation Training and ROHTAK 30 (B.Ed Spl 30 01262-212211 Research,(SIRTAR), , Gandhi Nagar, Rohtak Edu(MR) 01262-212066 (Co-Edu.) 01262-212065 11. Tika Ram College of Education, Sonepat SONEPAT 114 100 0130-2240508 (Co-Edu.) 12. Hindu College of Education, Sonepat SONEPAT 170 200 0130-2246558 (Co-Edu.) SELF FINANCING COLLEGES OF EDUCATION 13. 1*J.K. Memorial College of Education, VPO Birhi Kalan BHIWANI 100 50 01250-288761 4Dist. Bhiwani (Co-Edu.) (M)9315860516 . 14. 1Maharana Partap College of Education for Women, BHIWANI 100 100 01664-290003 5Meham Road, Vill. -

(S.S.A.) PERSPECTIVE PLAN 2003-2007 & Annual Work Plan & Budget 2003-2004 District-Jhajjar (Haryana) CONTENTS

A PROGRAMME FOR UNIVERSALISATION OF ELEMENTARY EDUCATION IN INDIA SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (S.S.A.) PERSPECTIVE PLAN 2003-2007 & Annual Work Plan & Budget 2003-2004 District-Jhajjar (Haryana) CONTENTS Sr. Name of the Chapter Page No, No. District Profile i) History 1-3 •0 Topography 3 III) Climate 4 iv) Geology 4 V) Basic Statistics 6-7 Vi) Demography 7 VII) Literacy 8 VKl) BPL Sun/ey 9 IX) Educational Institutions 9 *) Existing Incentive Scheme 10 Educational Profile 11 Table- 1.5 No. of Govt. Schools Blockwise. 11 Table 1 6 Blockwise No of Girls Pry. Schools. 11 Table 1 7 Clockwise No of Teachers in Pry,’ Schools 12 Table 1 9 Blockwise & Sexv.'ise No. of Scheduled Caste Teachers 12 Table 1 e Teachers position in upper primary school. 13 Table 1 10 CD Blockwise number of schools. 13 Table 111. Blockwise details of disabled children in the age group 6*14 years. 14 Table 1.12. Enrolmem of Anganwary centres as on 30-09-2002. 14 Table 1.13.Block wiso schools having primary teacher in position. 15 Table 1.14. Block wise head Teachers position in primary schools. 16 Table 1.15. Block-vy^se population in the age of 6-11. 16 Table 1.16 Block-wise total Enrolment in the age group of 6-11 16 Table 1.17 Block-wise Enrolment in Govt. Primary Schools. 17 Table 1.18 Biock-wise Enrolment in Govt, Primary Schools ( in %) 17 Table 1.19 Block-wise Enrolment in Private Primary School. 18 Table 1.20 BIcck-wise Enrolment in Private Primary School.(in %) 18 Table 1.21 Block-wise N.E.R, in the age group of 6-11 19 Table 1.22 Block-w/ise Retention in the age group of 6-11 19 Table 1.23 Block-wise Drop out in the age group of 6-11 20 Table 1.24 Block-wise Drop out in the age group of 6-11 (in %) 20 Table 1.25 Block-wise Non starter in the age group of 6-11 21 Tab's 1.26 Block-wise Non starter in the age group of 6-11 (in %) 21 Table 1.27 Block-wise out of school in the age group of 6-11 22 Table 1.28 Block-wise out of school in the age group of 6-11 (in %) 22 Table 1.29. -

Meham Assembly Haryana Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/HR-60-0118 ISBN : 978-93-5293-516-1 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 144 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-13 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 14-15 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

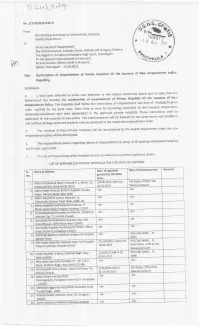

List of Empanelled Hospitals

a "[^: a , f \^ ' C- ft]^Y' t",l] Na. 21 27 6 | 2012-l H B-lll From Government, Haryana' /ff"u The Principal Secretary to Health DePartment. To t.,oW All the Heads of Departments \ Hissar, Rohtak and Gurgaon Division' R The Commissioners, Ambala, \^ The Registrar, Punjab and Haryana High Court' Chandigarh' \rl(qrr,xu All the Deputy Commissioners in Haryana ,r-y All Sub-Division Officer (Civil) in Haryana Dated Chandigarh 13'08.2015 the issuance of llew Empanelment policy- Sub:- Continuation of Empanelment of Private Hospitals till Regarding. Sir/Madam mentioned above and to state that the 2. l, have been directed to invite your attention to the subject Private Hospitalsi till the issuance of New Governmerlt has decided the continuation of ernpanelment of empanelment and that of Package/lmplant Ernpanelment Policy. The hospitals shall follow the instructions of treatment to the Haryana Government rates notified by the state Govt. from time to time for providing private hospitals' 'fhese instructions shall be employees/pensioners and their dependents in the approved be allowed on the same terms and conditions applicable till the issuance of new policy. The reimbursement will empanelment order' and notified package rates and implants rates as explained in the respective the Health Departrnent when the new 3. The renewal of these private Hospitals will be reconsidered by empanelment policy will be introduced' (2 years) of all existing empanelled hospitals 4. The empanelment orders regarding period of empanelment are hereby suPerseded. to continue is given as under:- 5. The list of Private Empanelled Hospitals which are aliowed L|sToFEMPANELLEDPR|VATEHOSP|TALSFoRTHESTATEoFHARYANA Remarks Date of aPProval Rate of reimbursement Sr. -

Haryana State Development Report

RYAN HA A Haryana Development Report PLANNING COMMISSION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI Published by ACADEMIC FOUNDATION NEW DELHI First Published in 2009 by e l e c t Academic Foundation x 2 AF 4772-73 / 23 Bharat Ram Road, (23 Ansari Road), Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002 (India). Phones : 23245001 / 02 / 03 / 04. Fax : +91-11-23245005. E-mail : [email protected] www.academicfoundation.com a o m Published under arrangement with : i t x 2 Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi. Copyright : Planning Commission, Government of India. Cover-design copyright : Academic Foundation, New Delhi. © 2009. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of, and acknowledgement of the publisher and the copyright holder. Cataloging in Publication Data--DK Courtesy: D.K. Agencies (P) Ltd. <[email protected]> Haryana development report / Planning Commission, Government of India. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 13: 9788171887132 ISBN 10: 8171887139 1. Haryana (India)--Economic conditions. 2. Haryana (India)--Economic policy. 3. Natural resources--India-- Haryana. I. India. Planning Commission. DDC 330.954 558 22 Designed and typeset by Italics India, New Delhi Printed and bound in India. LIST OF TABLES ARYAN 5 H A Core Committee (i) Dr. (Mrs.) Syeda Hameed Chairperson Member, Planning Commission, New Delhi (ii) Smt. Manjulika Gautam Member Senior Adviser (SP-N), Planning Commission, New Delhi (iii) Principal Secretary (Planning Department) Member Government of Haryana, Chandigarh (iv) Prof. Shri Bhagwan Dahiya Member (Co-opted) Director, Institute of Development Studies, Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak (v) Dr. -

Baseri & Bari, Bajri Mineapplicant Name

Project Name: Jainpur Unit-1 Sand UNIT, Sand mining (minor mineral) PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT District: Sonipat, Haryana M/s Shyam Jaina Ram. PRE- FEASIBILITY REPORT Vardan Environet, Gurgaon Page | 21 Project Name: Jainpur Unit-1 Sand UNIT, Sand mining (minor mineral) PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT District: Sonipat, Haryana M/s Shyam Jaina Ram. 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Letter of Intent (LOI) for mining contract Jainpur Unit-1, Sonipat for minor mineral sand over an area of 38.10 ha has been granted from Director Mines & Geology department, Chandigarh, Haryana,. Memo No. DMG/Hy/Cont/Jainpur-1/2015/319 dated 21/01/2015, for the period of 9 year to M/s Shyam Jaina Ram (Copy enclosed as Annexure-I) The proposed production capacity of sand is 14.35 Lakhs MTPA. The contract area lies on Yamuna riverbed/Private Agricultural land. The total mine contract area is 38.10 ha which is non-forest land. The proposed mining contract project covered the riverbed/Private agriculture land. 1. Jainpur-1 River bed Block (area of 28.10 Ha.) 2. Jainpur-1 Outside River bed Block (area of 10.00 ha) The period of contract shall be 9 years and same shall commence with effect from date of grant of Environmental Clearance by the competent authority or on expiry of 12 months from the date of issuance of Letter of Intent, whichever is earlier. The following special conditions shall be applicable for the excavation of minor mineral from river beds in order to ensure safety of river-beds, structures and the adjoining areas: a. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Rohtak, Part XII-A & B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE &TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT ROHTAfK v.s. CHAUDHRI DI rector of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, ]993 HARYANA DISTRICT ROHTAK Km5 0 5 10 15 10Km bLa:::EL__ :L I _ b -~ (Jl o DISTRICT ROHTAK CHANGE IN JURISDICTION 1981-91 z Km 10 0 10 Km L-.L__j o fTI r BOUNDARY, STATE! UNION TERRi10RY DIS TRICT TAHSIL AREA GAINED FROM DISTRIC1 SONIPAT AREA GAINED FROM DISTRICT HISAR \[? De/fl/ ..... AREA LOST TO DISTRICT SONIPAT AREA LOST TO NEWLY CREATED \ DISTRICT REWARI t-,· ~ .'7;URt[oN~ PART OF TAHSIL JHAJJAR OF ROHTAK FALLS IN C.D,BLO,CK DADRI-I . l...../'. ",evA DISTRICT BHIWANI \ ,CJ ~Q . , ~ I C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY "- EXCLUDES STATUTORY ~:'"t -BOUNDARY, STATE I UNION TERRITORY TOWN (S) ',1 DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED TAHSIL. UPTO I. 1.1990 C.D.BLOCK HEADQUARTERS '. DISTRICT; TAHSIL; C. D. BLOCK. NATIONAL HIGHWAY STATE HIGHWAY SH 20 C. O. BLOCKS IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD RS A MUNDlANA H SAMPLA RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION, BROAD GAUGE IiiiiI METRE GAUGE RS B GOHANA I BERI CANAL 111111""1111111 VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME Jagsi C KATHURA J JHAJJAR URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,!I,lII, IV & V" ••• ••• 0 LAKHAN MAJRA K MATENHAIL POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION .. [liiJ C'a E MAHAM L SAHLAWAS REST ClOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW' AND CANAL BUNGALOW RH, TB, CB F KALANAUR BAHADURGARH Other villages having PTO IRH/TBIC8 ~tc.,are shown as. -

Department of School Education, Government of Haryana

Department of School Education, Government of Haryana List of Private High Schools as on 11 Jul, 2019 05:01:20 PM Boys/Girls/Co-Ed Assembly Parliamentry Sr. No. School Name School Code UDISE Code District Block Rural/Urban Constituency Constituency 1 Asa Ram Senior 27675 06020102906 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Urban 04-Ambala Cantt 01-Ambala (SC) Secondary Public PC School Kuldeep Nagar Amabala Cantt 2 Lehna Singh 27297 06020113006 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Urban 05-Ambala City 01-Ambala (SC) S.D.Girls High PC School, Model Town, Ambala City 3 ST FRANCIS 28953 06020502003 Co-Edu Ambala Naraingarh Rural 03-Nariangarh 01-Ambala (SC) ACADEMY PC SCHOOL 4 Jasper School 27043 06020101707 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Urban 05-Ambala City 01-Ambala (SC) PC 5 The Scholars 28488 06020105306 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Rural 05-Ambala City 01-Ambala (SC) PC 6 E Max 26894 06020305003 Co-Edu Ambala Saha Rural 06-Mullana 01-Ambala (SC) International PC School 7 BHARTIYA 20008 06020106804 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Rural 06-Mullana 01-Ambala (SC) VIDYA MANDIR PC 8 GURU TEG 20023 06020110504 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Rural 05-Ambala City 01-Ambala (SC) BAHADUR PC SCHOOL 9 MATA PARVATI 20029 06020106803 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Rural 04-Ambala Cantt 01-Ambala (SC) HIGH SCHOOL PC 10 ST. JOSEPH 20057 06020113063 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Urban 05-Ambala City 01-Ambala (SC) HIGH SCHOOL PC 11 ASA RAM 20066 06020205605 Co-Edu Ambala Ambala-I (City) Urban 04-Ambala Cantt 01-Ambala (SC) PUBLIC PC Report Generated by RTE on 11 Jul, 2019 05:01:20 PM 1 of 155 Boys/Girls/Co-Ed Assembly Parliamentry Sr.