A Corncrake Story,’71,Music in Fermanagh,Elemenopy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sunday Newsletter Knockninny

The Sunday Newsletter Knockninny ST NINNIDH’S CHURCH DERRYLIN 16th August 2020 Twentieth Sunday in Ordinary Time Fr. Gerard Alwill P.P. Phone no. 028 6774 8315 mobile 00353 872305557. parish email [email protected]. Mass Intentions: Sat 15 August: 8pm: Paddy Clarke (Mullyneeny) AND Phil, Margaret & Tony McCaffrey (Fortlea) Sun 16 August: 11.15am: Tom Blake Month's Mind Mon 17th Aug: 10.00am: Special Intention Tues 18th Aug:10.00am: Special Intention Wed 19th Aug: 10.00am: Special Intention Thur 20th Aug:10.00am: Special Intention Fri 21st Aug: 10.00am: Special Intention Sat 22nd Aug: 8.00pm Bridget Murphy (Corraveigha) AND Eamon Reilly & Family (Aughyoule) and Smith family (Camletter) Sun 23rd Aug: 11.15am: Patricia Farrelly (Memorial Mass) Joe Shannon RIP: Please pray for the happy repose of the soul of Joe Shannon, formerly of Derrylin, who died in Coventry, England, on Tuesday, 11th August. Saturday 15th August 8.00pm: Reader: Ellie Clarke Eucharistic Ministers: Valerie McManus Philip McCarron Sunday 16th August 11.15am: Reader: Molly Flanagan Eucharistic Ministers: Caroline Flanagan, Jackie McKenna Saturday 22nd August 8.00pm: Reader Orlaith McIntyre Eucharistic Ministers: Connie Murphy Sunday 23rd August 11.15am: Reader: Caitlin McIntyre Eucharistic Ministers: Anne McBrien, Tomas Scallon Sacrament of Confirmation: The celebration of the Sacrament of Confirmation will take place in St Mary’s Church, Teemore, at 6.00pm on Friday 28th August, and in St Ninnidh’s Church, Derrylin, at 4pm on Saturday 29th August. Rehearsals: The Confirmation rehearsals will take place in St Mary's Church on Wednesday, 26th August at 8pm and St Ninnidh's Church on Thursday, 27th August at 8pm. -

CHURCH of IRELAND the Clogher Diocesan MAGAZINE

CHURCH OF IRELAND The Clogher Diocesan MAGAZINE Member of the worldwide Anglican Communion November 2013 | £1 Celebration of music in Monaghan Church ChristmasChristmas ConcertConcert inin EnniskillenEnniskillen CathedralCathedral withwith NathanNathan CarterCarter Visit by the Archbishop of Hong Kong www.clogher.anglican.org Gardening Services NO JOB TOO LARGE OR TOO SMALL. For all your gardening needs. • Power Washing • Hedge Cutting We do a wide range of jobs at • Timber Cutting • Sheds Cleaned reasonable prices. • Logs Split • Fences and Walls painted Contact Noel on: 028 89 521736 or Mobile 07796 640514 A. S. Oil Boiler and ARMSTRONG Cooker Services Funeral Directors & Memorials • Servicing, Commissioning, Repair & Installation of Oil Fired Boilers / Cookers (All models) • A dignifed and personal 24hr service • Out of Office and 24 Emergency Service can be provided • Offering a caring and professional service • An efficient and effective service using latest technology • Memorials supplied and erected • A timely reminder sent out when your next service is • Large selection of headstones, vases open books due (12 months). • Open books & chipping’s • All harmful fumes eliminated i.e. Carbon monoxide • Also cleaning and renovations (Computer printout given.) to existing memorials • Fires / chimneys cleaned and repaired • Additional lettering • Special offers on all church properties • Qualified OFTEC Te c h n i c i a n 101, 102, 105 & 600A Dromore Tel. • Also, small plumbing jobs carried out 028 8289 8424 We also specialise in making remote oil storage Omagh Tel. tanks vandal proof, which can also provide 028 8224 0803 secondary containment for a tank that is not Robert Mob. bundled (therefore very often not covered by 077 9870 0793 insurance in the event of a spillage) Derek Mob. -

Visitor Map Attractions Activities Restaurants & Pubs Shopping Transport Fermanaghlakelands.Com Frances Morris Studio | Gallery Angela Kelly Jewellery

Experience Country Estate Living on a Private Island on Lough Erne. Northern Ireland’s Centrally located with Choice of Food & Only 4 Star Motel lots to see & do nearby Drink nearby Enjoy a stay at the beautifully restored 4* Courtyards,Cottages & Coach Houses. Award Winning Belle Isle Cookery School. Boating, Fishing, Mountain Biking & Bicycle Hire available. Choice of accommodation 4 Meeting & The Lodge At Lough Erne, variety of room types Event spaces our sister property Pet Friendly Accommodation & Free Wi-Fi. Book online www.motel.co.uk or contact our award winning reception T. 028 6632 6633 | E. [email protected] www.belle-isle.com | [email protected] | tel: 028 6638 7231 Tempo Road | Enniskillen | BT74 6HX | Co. Fermanagh NORTHERN IRELAND Monea Castle Visitor Map Attractions Activities Restaurants & Pubs Shopping Transport fermanaghlakelands.com Frances Morris Studio | Gallery Angela Kelly Jewellery l Original Landscapes Unique Irish Stone & Silver Jewellery l Limited Edition Prints Contemporary & Celtic Designs l Photographic Images One-off pieces a speciality 16 The Buttermarket Craft & Design Centre Market House, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, BT74 7DU 17 The Buttermarket Craft Centre, T: 028 66328741/ 0792 9337620 Enniskillen | Co. Fermanagh | BT74 7DU [email protected] T: 0044(0) 2866328645 | M: 0044(0) 7779787322 E: [email protected] www.francesmorris.com www.angelakellyjewellery.com Activities Bawnacre Centre Castle Street, Irvinestown 028 6862 1177 MAP1 E2 Blaney Caravan Park Belle Isle Estate & Belle Isle -

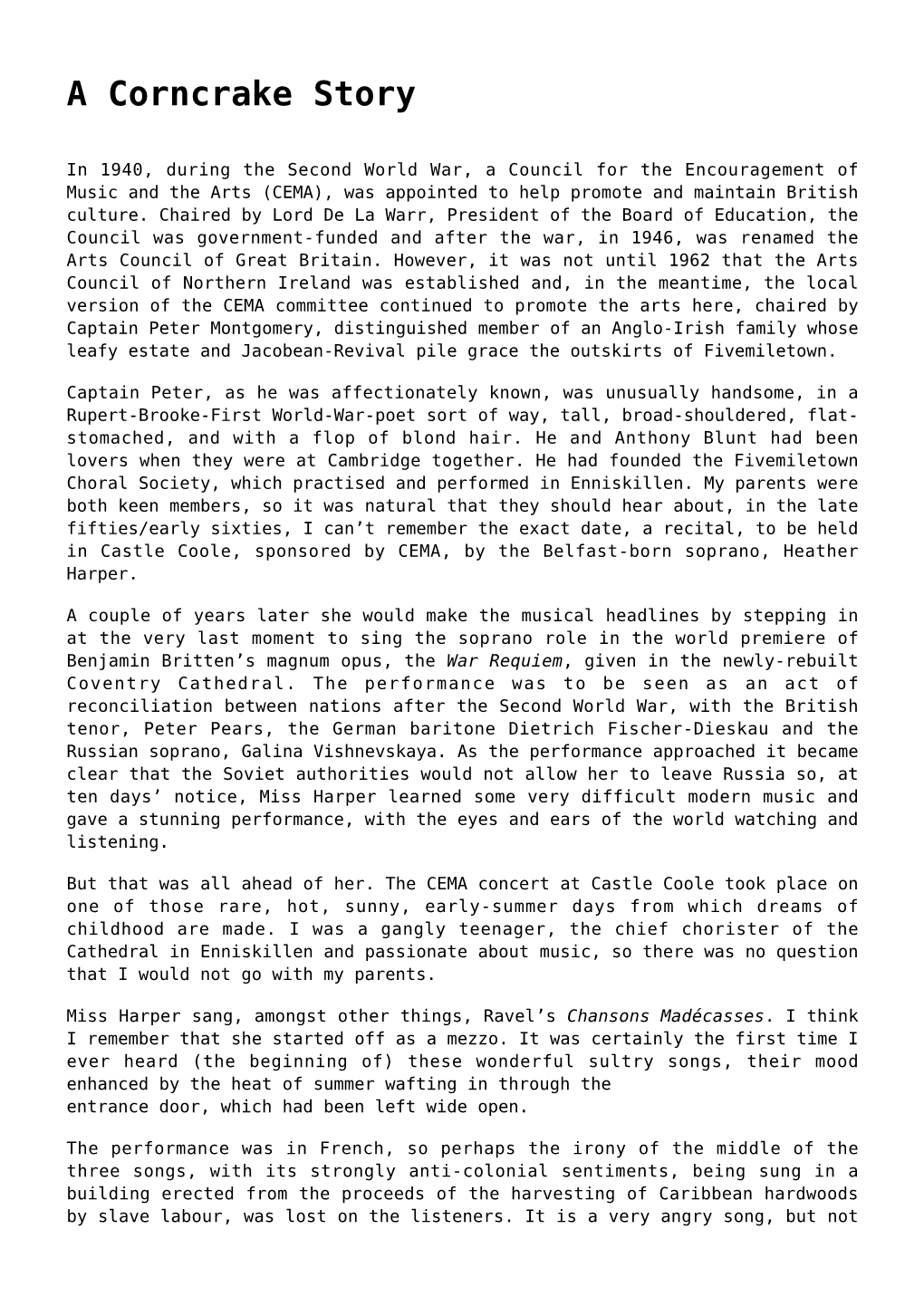

A Revised List of the Executive Assets in County Fermanagh Is Provided and an Update Will Be Provided to the Assembly Library

Conor Murphy MLA Minister of Finance Clare House, 303 Airport Road West Belfast BT3 9ED Mr Seán Lynch MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Parliament Buildings Stormont AQW: 6772/16-21 Mr Seán Lynch MLA has asked: To ask the Minister of Finance for a list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh. ANSWER A revised list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh is provided and an update will be provided to the Assembly Library. Signed: Conor Murphy MLA Date: 3rd September 2020 AQW 6772/16-21 Revised response DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers -

Area Profile of Ballinamallard

‘The Way It Is’ Area Profiles A Comprehensive Review of Community Development and Community Relationships in County Fermanagh December 98 AREA PROFILE OF BALLINAMALLARD (Including The Townland Communities Of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy, Killadeas And Kilskeery). Description of the Area Ballinamallard is a small village, approximately five miles North of Enniskillen; it is located off the main A32, Enniskillen to Irvinestown road on the B46, Enniskillen to Dromore road. Due to its close proximity to Enniskillen, many of the residents work there and Ballinamallard is now almost a ‘dormitory’ village - house prices are relatively cheaper than Enniskillen, but it is still convenient to this major settlement. With Irvinestown, located four miles to its North, the village has been ‘squeezed’ by two economically stronger settlements. STATISTICAL SUMMARY: BALLINAMALLARD AREA (SUB-AREAS: WHITEHILL, TRORY, BALLYCASSIDY, KILLADEAS) POPULATION: Total 2439 Male 1260 (51.7%) Female 1179 (48.3%) POPULATION CHANGE 1971-1991: 1971 1991 GROWTH 2396 2439 1.8% HOUSEHOLDS: 794 OCCUPANCY DENSITY: 3.07 Persons per House. DEPRIVATION: OVERALL WARD: Not Deprived (367th in Northern Ireland) Fourth Most Prosperous in Fermanagh ENUMERATION DISTRICTS: NINE IN TOTAL Four Are Deprived One In The Worst 20% in Northern Ireland UNEMPLOYMENT (September 1998): MALES 35 FEMALES 18 OVERALL 53 RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION: CATHOLIC: 15.7% PROTESTANT: 68.2% OTHERS / NO RESPONSE: 16.1% Socio-Economic Background: The following paragraphs provide a review of the demographic, social and economic statistics relating to Ballinamallard village and the surrounding townland communities of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy and Killadeas. According to the 1991 Census, 2439 persons resided in the Ballinamallard ward, comprising 1260 males and 1179 females; the population represents 4.5% of Fermanagh’s population and 0.15% of that of Northern Ireland. -

Building Control & Licensing Report (Paper E

Report to: Environmental Services Committee Agenda Item: 4.4 Report Title: Building Control & Licensing Report (Paper E) th (Period 1 – 25 March 2015) th Date: 8 April 2015 Report by: Director of Environment and Place For Publication: Yes If 'not for publication', Insert reference to grounds upon which information is deemed 'confidential' [ref Local Government (Northern Ireland) Act 2014 section 42(2), (3)] or 'exempt' [ref Local Government (Northern Ireland) Act 2014 section 42(4) Schedule 6]: (i) Confidential grounds: N/A (ii) Exempt grounds: N/A 1. Relevant Background and Introduction 1.1 The aim of the Building Control and Licensing Department is to protect people and the environment by ensuring safe, sustainable and accessible building for all. The Department is responsible for the following key areas:- Building Control Regulations Property Certificate Administration Postal Naming and Numbering Licensing Animal Welfare and Dog Control Off Street Car Parking Compliance – Clean Neighbourhood Others 1.2 The Director and Head of Service have delegated powers in respect of Building Control and Licensing Legislation (as approved by Fermanagh and Omagh District Council – Scheme of Delegation), designed to ensure speedier decision making and improved efficiency. 2. Key Issues 2.1 BUILDING CONTROL REPORT 2.1.1 BUILDING REGULATIONS (NORTHERN IRELAND) 2012 (as amended) The attached Building Control Report indicates the number of applications Approved, Accepted, Granted, Rejected, and Cancelled in accordance with the Building Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2012 (as amended) – See Appendix 1 2.1.2 UNAUTHORISED DEVELOPMENTS Details have been requested in respect of the following developments on which work has commenced, apparently without approval. -

Constituency Profile Fermanagh and South Tyrone – June 2016

Constituency Profile Fermanagh and South Tyrone – June 2016 Constituency Profile – Fermanagh and South Tyrone June 2016 About this Report Welcome to the June 2016 Constituency Profile for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. This profile has been produced by the Northern Ireland Assembly’s Research and Information Service (RaISe) to support the work of Members. The report includes a demographic profile of Fermanagh and South Tyrone and indicators of Health, Education, Employment, Business, Low Income, Crime and Traffic and Travel. For each indicator, this profile presents: . The most up-to-date information available for Fermanagh and South Tyrone; . How Fermanagh and South Tyrone compares with the Northern Ireland average; and . How Fermanagh and South Tyrone compares with the other 17 Constituencies in Northern Ireland. For a number of indicators, ward level data1 is provided demonstrating similarities and differences within the constituency. A summary table has been provided showing the latest available data for each indicator, as well as previous data, illustrating change over time. Constituency Profiles are also available for each of the other 17 Constituencies in Northern Ireland and can be accessed via the Northern Ireland Assembly website. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/assembly-business/research-and-information-service-raise/ The data used to produce this report has been obtained from the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency’s Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS). To access the full range of information available on NINIS, please visit: http://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/ Please note that the figures contained in this report may not be comparable with those in previous Constituency Profiles as figures are sometimes revised and as more up-to-date mid-year estimates are published. -

2019-Summer-Activities-Brochure.Pdf

Activity Date Time Age Cost / Application Procedure Junior tennis Camp 29 July - 2 August Various All Ages Please contact Bawnacre Centre Arts & Crafts 29 July - 2 August 11 - 1pm 5 - 9 years £15 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Arts & Crafts 29 July - 2 August 2 - 4pm 10 - 16 years £15 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Gymnastics 5 - 9 August 11 - 1pm 6 - 8 years £20 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Gymnastics 5 - 9 August 2 - 4pm 9 - 16 years £20 Please contact Bawnacre to register Junior Open Tennis Championships 5 - 10 August Various All Ages Free - Please contact Bawnacre Centre Dodgeball 7 August 11.30 - 1pm 12+ £3 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register All Ireland Inter-Provincial Junior Tennis 12 - 15 August Various U14 + U18 Teams already selected but Championships spectators welcome to watch Football 21 - 23 August 2 - 4pm 6 - 12 £9 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Activity Date Time Age Cost / Application Procedure Beginners Summer Drumming Work- 1 - 5 July Various 7 - 11 years Register at Bawnacre Centre shop Gaa Cul Camp 1 - 5 July Various Primary Register at Bawnacre Centre School Hockey 1 - 5 July 11am-1pm 6 -12 years £15 Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Goal Ball Activity Session 10 July 10am - 11.30am 8 - 17 years Free - Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Sensory Activity Session 10 July 12noon - 1.30pm 8 - 17 years Free - Please contact Bawnacre Centre to register Bonny Baby Competition 13 July 2pm 1 - 3 years Free - Enter on the day Pet Show 13 July 2.30pm -

Shopping Guide

fermanaghlakelands.com Shopping Directory Page 1 Ballinamallard 6 2 Bellanaleck 6 3 Belleek 7 4 Irvinestown 8 5 Lisnaskea 9 6 Enniskillen 12 Arts & Crafts 22 Welcome A little bit of what you extra’ which reflects the Courtyard environment stunning showroom fancy does you good, so excellent service for which at the Buttermarket Craft and purchase a piece of they say, so therefore the county is reputed. & Design Centre and pottery to take home. search, browse, unearth appreciate the artists at and admire a bargain in Or slow the pace down a work in their studios which In addition to an award an unrivalled shopping little in one of our smaller showcase Fermanagh’s winning museum, The experience in Fermanagh. market towns – why not rich craft offering. Sheelin Lace Shop in combine a day’s shopping Bellanaleck is a treasure The vibrant streets of the with one of the festival For an absolutely unique trove of antique Irish lace principal ‘island town’ events taking place. retail experience why items and other vintage of Enniskillen provides not visit either Belleek textiles and clothing. The a large choice of well- You’ll be spoilt for choice, Pottery or the Sheelin perfect opportunity to known high street names whether you’re looking to Lace Museum. Belleek pick up something you and a fantastic range of indulge in some serious Pottery is the oldest will cherish forever! products but also local retail therapy or simply working pottery in Ireland, and specialty shops, relax and browse with founded in 1857. Take a There are many reasons independent boutiques the occasional stop-off tour and discover how this to visit and shop in and family run businesses in order to recharge fine Parian china, known Fermanagh, where there’s which cater for both the with a coffee or a bite throughout the world, something for everyone, holidaymaker and the local to eat and drink. -

Co. FERMANAGH POST OFFICES Compiled by Ken Smith (Updated 14/2/2020)

Co. FERMANAGH POST OFFICES compiled by Ken Smith (updated 14/2/2020). Aghalane 1899: BELTURBET. Rubber issued 30-3-1899. 1-2-1922 ENNISKILLEN (tc.23-7-1997: re-open 15-9-1997) Closed 24-11-2003. Arney 1859: ENNISKILLEN. Rubber 1886. Replaced by 'Five Points' 1954/55. Ballinamallard 24-9-1834: PP. ENNISKILLEN. 2-10-1865 RSO. MO-SB 1-2-1883. T.O.3-5-1892(BQI). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 3-5-1941 ENNISKILLEN (to Spar 16-4-2015, PO Local). Ballindarragh 1853 'Ballindarra' LISNASKEA. Closed c.Oct.1859. Re-estd.1879: CLONES,Co.Mon. By 1886 LISNASKEA RSO. Rubber 1904. 'Ballindarragh' by 1926. 18-12-1940 ENNISKILLEN. Closed by 14/2/2020. Ballycassidy 1852: ENNISKILLEN. 2-10-1865 RSO. By 7/1890 BALLINAMALLARD RSO. Rubber 1891. MO-SB by 1897: discont.1-12-1901. T.O.16-11-1942(BLN). 3-5-1941 ENNISKILLEN. Closed 4-11-2008 (replaced by Home Service). Ballyreagh 1877: ENNISKILLEN. By 1885 LISBELLAW RSO. 1890 TEMPO S.O. 1896 LISBELLAW RSO. Rubber 1898. 1-3-1902 TEMPO. Closed 1916 (July-Dec) Belcoo 1923 (poc.3/12/1923) MO-SB: ENNISKILLEN. Closed April 2016. PO Local, Spar, 6-7-2016. Bellanaleck 1900: ENNISKILLEN. Rubber issued 23-4-1900. T.O.7-12-1938(JNZ). Belleek 26-5-1833: PP. BALLYSHANNON (&1848). By 1855 ENNISKILLEN. M.O.1-1-1864. S.B.28-3-1864. 2-10-1865 RSO. T.O.27-7-1871(BZA). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 12-2-1930 ENNISKILLEN. 1-4-1935 POST TOWN. 3-5-1941 ENNISKILLEN >PO Local 12-5-2016. -

Newsletter 29-1D

UK Belleek Collectors’ Group Newsletter 29/1 April 2008 UK Belleek Collectors’ Group Newsletter Number 29/1 Apri l 2008 Spring Special Research Issue Brian Russell on Masonic Ware: some fabulous previously unrecorded items Tony Fox ––– Part 5 of Teaware: Shamrock pattern in all its variety…variety… Pat and Paul Tubb investigate more Belleek people David Reynolds on the lookout for Belleek images in unexpected places And… Glenda and Paul Norman on a Page peculiar 111 New Zealand phenomphenomeeeenon.non. UK Belleek Collectors’ Group Newsletter 29/1 April 2008 Contacts: Chris Marvell is the Newsletter editor. Please let him have your contributions for future Newsletters, comments, suggestions, letters for publication, criticisms etc. If you want, Gina Kelland is still happy to receive material for the Newsletter: she will be assisting Chris with her advice and proofreading. If you are sending published articles please either get Copyright clearance yourself or enclose the details of the publisher so Chris can ask for permission. You can contact Chris by email to [email protected] Chris and Bev Marvell publish and distribute the Newsletter. Chris has set up a database which forms the Group’s “digital” archive, keeping a record of relevant publications and photographs (including photos etc. gathered at meetings and not published in the Newsletter). Some or all of this information will be available on the Internet as our website develops - working with Simon Whitlock, we intend to publish all the back issues of the Newsletter and all of the research done by our Group members on our website. If you have questions about the publication and distribution of the Newsletter, contact Chris or Bev by email at [email protected] . -

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

194 / 195 Pettigo - Belleek Mondays to Fridays Service 194b 194 194c 194b 194c 194i 194b 194d Vehicle Type LF LF Service Restrictions 1 Enniskillen, Enniskillen Bus Station 0650 0925 1030 1135 1415 1535 1555 1750 Drumclay, South West Acute Hospital Grounds 0700 0935 1040 1145 1425 1605 1800 Ballinamallard, Main Street 0710 0945 1050 1155 1435 1550 1615 1810 Irvinestown, By-Pass 0720 0955 1100 1205 1445 1600 1625 1820 Lisnarick, Connolly Park 0725 1000 1210 1607 1630 1825 Kesh, Post Office 0730 1005 1215 1615 1635 1830 Ederney, McKerveys Shop 1835 Kesh, Pettigo HM Customs 0740 1225 1645 1851 Scardans, Castlecaldwell Village 1235 Belleek, Post Office 1245 Belleek, Ballyshannon Bus Station 1255 Bundoran, Astoria Road 1305 Saturdays Service 194c 194b 194d Enniskillen, Enniskillen Bus Station 1030 1305 1710 Drumclay, South West Acute Hospital Grounds 1040 1315 1720 Ballinamallard, Main Street 1050 1325 1730 Irvinestown, By-Pass 1100 1335 1740 Lisnarick, Connolly Park 1340 1745 Kesh, Post Office 1345 1750 Ederney, McKerveys Shop 1756 Kesh, Pettigo HM Customs 1355 1812 Scardans, Castlecaldwell Village 1407 Belleek, Post Office 1415 Belleek, Ballyshannon Bus Station 1425 Bundoran, Astoria Road 1435 Sundays no service Service Restrictions: 1 - until 15 Jan 2021 Notes: LF - Operated by Low Floor vehicles 194 / 195 Belleek - Pettigo Mondays to Fridays Service 194a 194c 194b 194d 194j 194a 194a Vehicle Type LF LF LF LF Service Restrictions 1 Bundoran, Astoria Road 1310 Belleek, Ballyshannon Bus Station 1320 Belleek, Post Office 1330 Scardans, Castlecaldwell