The Perfect Coquette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Dolce Vita Actress Anita Ekberg Dies at 83

La Dolce Vita actress Anita Ekberg dies at 83 Posted by TBN_Staff On 01/12/2015 (29 September 1931 – 11 January 2015) Kerstin Anita Marianne Ekberg was a Swedish actress, model, and sex symbol, active primarily in Italy. She is best known for her role as Sylvia in the Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita (1960), which features a scene of her cavorting in Rome's Trevi Fountain alongside Marcello Mastroianni. Both of Ekberg's marriages were to actors. She was wed to Anthony Steel from 1956 until their divorce in 1959 and to Rik Van Nutter from 1963 until their divorce in 1975. In one interview, she said she wished she had a child, but stated the opposite on another occasion. Ekberg was often outspoken in interviews, e.g., naming famous people she couldn’t bear. She was also frequently quoted as saying that it was Fellini who owed his success to her, not the other way around: "They would like to keep up the story that Fellini made me famous, Fellini discovered me", she said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. Ekberg did not live in Sweden after the early 1950s and rarely visited the country. However, she welcomed Swedish journalists into her house outside Rome and in 2005 appeared on the popular radio program Sommar, and talked about her life. She stated in an interview that she would not move back to Sweden before her death since she would be buried there. On 19 July 2009, she was admitted to the San Giovanni Hospital in Rome after falling ill in her home in Genzano according to a medical official in the hospital's neurosurgery department. -

LCCC Thematic List

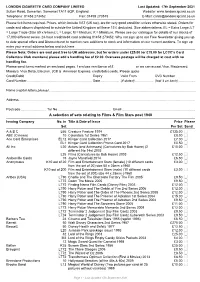

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

From 5 to 13 October at Fiere Di Parma

Press Release MERCANTEINFIERA AUTUMN THE POETRY OF THE HEEL, ITALIAN MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND FOUR CENTURIES OF ART HISTORY From 5 to 13 October at Fiere di Parma Mercanteinfiera, the Fiere di Parma international exhibition of antiques, modern antiques, design and vintage collectibles, is an increasingly “fusion” event. Protagonists of the 38th edition are the Villa Foscarini Rossi Shoes Museum of the LVMH Group and the BDC Art Gallery in Parma, owned by Lucia Bonanni ad Mauro del Rio, curators of the two collateral exhibitions. On the one hand, stylists such as Dior, Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent and Nicholas Kirkwood highlighted by the far-sightedness of the entrepreneur Luigino Rossi, the Muse- um’s founder. On the other, masters of the visual language such as Ghirri, Sottsass, Jodice, as well as the paparazzi. With Lino Nanni and Elio Sorci, we will dive into the years of the exuberant Dolce Vita. (Parma, 30 September 2019) - At the beginning there were” pianelle”, or “chopines”, worn by both aristocratic women and commoners to protect their feet from mud and dirt. They could be as high as 50 cm (but only for the richest ladies), while four centuries later Mari- lyn Monroe would build her image on a relatively very modest 11-cm peep toe heel. For Yves Saint Laurent the perfect stride required a 9-cm heel. This was too high for the Swinging Sixties of London and Twiggy, when ballerinas were the footwear of choice. Whether high, low, with a 9 or 11cm heel, shoes have always been the best-loved accesso- ry of fashion victims and many others and they are the protagonists of the collateral exhi- bition “In her Shoes. -

SAAS Conference Program (P

Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood Wallengren, Ann-Kristin 2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wallengren, A-K. (2018). Celebrated, Contested, Criticized: Anita Ekberg, a Swedish Sex Goddess in Hollywood. 34. Abstract from The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS), . Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 10th Biennial Conference of The Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) OPEN COVENANTS: PASTS AND FUTURES OF GLOBAL AMERICA Friday September 28th – Sunday September 30th 2018 Stockholm, Sweden PROGRAM MAGNUS BERGVALLS STIFTELSE Welcome to the 10th biennial conference of the Swedish Association for American Studies (SAAS) Stockholm, September 28–30, 2018 Keynote speakers: Prof. -

La Dolce Vita Nothing but the Best Is Good Enough for You

La Dolce Vita Nothing but the best is good enough for you La Dolce Vita Nothing but the best is good enough for you La The phrase comes from the title of a famous Federico Fellini movie, with a memorable scene in which Marcello Dolce Mastroianni bathes with alluring Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain in Rome, late at night. La dolce vita, actually, is much more than enjoying life’s most epicurean Vita and seductive joys, it is at once a community lifestyle and a state-of-mind, a way of being in the world and of the world. The expression comes from the title of a famous Federico Fellini movie. In a memorable scene, Marcello Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg take a late night dip in Rome’s Trevi fountain. In truth, “la dolce vita” is much more than enjoying life’s seductive pleasures. It is a lifestyle, a state-of-mind... La Dolce Vita “La dolce vita”… dreamily pronounced, is an iconic Italian expression. The “sweet life” conveys that relaxed, pleasure-filled lifestyle that Italians are known to seek and cultivate. This is at the heart of an unforgettable Italian vacation. Passionately devoted to this philosophy Italy’s Finest is delighted to present the ultimate Italian experience: La Dolce Vita Vacation. La Dolce Vita Beloved FAMILY, cherished FRIENDS and delicious FOOD are the indispensable values the Italians treasure. Living life to its fullest means savoring these pleasures leisurely, every day. Wishes Desires& Breathtaking natural beauty, unrivaled artistic heritage and Which are the indispensable elements in life, those lively traditions from the Alps to values that Italians pursue, treasure and bravely defend Sicily. -

La Cultura Italiana

LA CULTURA ITALIANA FEDERICO FELLINI (1920-1993) This month’s essay continues a theme that several prior essays discussed concerning fa- mous Italian film directors of the post-World War II era. We earlier discussed Neorealism as the film genre of these directors. The director we are considering in this essay both worked in that genre and carried it beyond its limits to develop an approach that moved Neoreal- ism to a new level. Over the decades of the latter-half of the 20th century, his films became increasingly original and subjective, and consequently more controversial and less commercial. His style evolved from Neorealism to fanciful Neorealism to surrealism, in which he discarded narrative story lines for free-flowing, free-wheeling memoirs. Throughout his career, he focused on his per- sonal vision of society and his preoccupation with the relationships between men and women and between sex and love. An avowed anticleric, he was also deeply concerned with personal guilt and alienation. His films are spiced with artifice (masks, masquerades and circuses), startling faces, the rococo and the outlandish, the prisms through which he sometimes viewed life. But as Vincent Canby, the chief film critic of The New York Times, observed in 1985: “What’s important are not the prisms, though they are arresting, but the world he shows us: a place whose spectacularly grand, studio-built artificiality makes us see the interior truth of what is taken to be the ‘real’ world outside, which is a circus.” In addition to his achievements in this regard, we are also con- sidering him because of the 100th anniversary of his birth. -

An Homage to Marcello Mastroianni Saturday, September 22, 2018 Castro Theatre, San Francisco

Ciao, Marcello! An Homage to Marcello Mastroianni Saturday, September 22, 2018 Castro Theatre, San Francisco An overdue homage to a great star 60 years after the making of “La Dolce Vita”, featuring the works of four directors for one actor in one day. Presented in collaboration with The Leonardo da Vinci Society, The Consul General of Italy and The Italian Cultural Institute of San Francisco. With gratitude to Luce Cinecittá, Janus Films, Kino Lorber, and Paramount Pictures. Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1963) 119 min. BD 10:00 AM Directed by Vittorio De Sica with Sophia Loren 8½ (1963) 138 min. 35 mm 1:00 PM Directed by Federico Fellini with Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimèe, Sandra Milo A Special Day (1977) 106 min. 35 mm 3:30 PM Directed by Ettore Scola with Sophia Loren La Dolce Vita (1960) 173 min. DCP 6:00 PM Directed by Federico Fellini with Anita Ekberg Via Veneto Party 9:00 PM-10:30 PM Divorce Italian Style (1961) 105 min. 35 mm 10:30 PM Directed by Pietro Germi with Daniela Rocca, Stefania Sandrelli Marcello Mastroianni A more intimate Marcello, who after the 10 years in the theater under the artistic wing of Luchino Visconti, arrives to the big success of “La Dolce Vita”, never forgetting the intimate life of the average Italian of the time. He molds and changes according to the director that he works with, giving us a kaleidoscope of images of Italy of the 60s. Marcello said: “Yes! I confess, I prefer cinema to theater. Yes, I prefer it for approximation and improvisations, for its confusion. -

Federico Fellini: a Life in Film

Federico Fellini: a life in film Federico Fellini was born in Rimini, the Marché, on 20th January 1920. He is recognized as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time. His films have ranked in polls such as ‘Cahiers du cinéma’ and ‘Sight & Sound’, which lists his 1963 film “8½” as the 10th-greatest film. Fellini won the ‘Palme d'Or’ for “La Dolce Vita”, he was nominated for twelve 'Academy Awards', and won four in the category of 'Best Foreign Language Film', the most for any director in the history of the Academy. He received an honorary award for 'Lifetime Achievement' at the 65th Academy Awards in Los Angeles. His other well-known films include 'I Vitelloni' (1953), 'La Strada' (1954), 'Nights of Cabiria' (1957), 'Juliet of the Spirits' (1967), 'Satyricon' (1969), 'Roma' (1972), 'Amarcord' (1973) and 'Fellini's Casanova' (1976). In 1939, he enrolled in the law school of the University of Rome - to please his parents. It seems that he never attended a class. He signed up as a junior reporter for two Roman daily papers: 'Il Piccolo' and 'lI Popolo di Roma' but resigned from both after a short time. He submitted articles to a bi- weekly humour magazine, 'Marc’Aurelio', and after 4 months joined the editorial board, writing a very successful regular column “But are you listening?” Through this work he established connections with show business and cinema and he began writing radio sketches and jokes for films. He achieved his first film credit - not yet 20 - as a comedy writer in “Il pirato sono io” (literally, “I am a pirate”), translated into English as “The Pirate’s Dream”. -

The Dark Side of Hollywood

TCM Presents: The Dark Side of Hollywood Side of The Dark Presents: TCM I New York I November 20, 2018 New York Bonhams 580 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 24838 Presents +1 212 644 9001 bonhams.com The Dark Side of Hollywood AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 New York | November 20, 2018 TCM Presents... The Dark Side of Hollywood Tuesday November 20, 2018 at 1pm New York BONHAMS Please note that bids must be ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION 580 Madison Avenue submitted no later than 4pm on Front cover: lot 191 IMPORTANT NOTICE New York, New York 10022 the day prior to the auction. New Inside front cover: lot 191 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com bidders must also provide proof Table of Contents: lot 179 irrespective of any previous activity of identity and address when Session page 1: lot 102 with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW submitting bids. Session page 2: lot 131 complete the Bidder Registration Los Angeles Session page 3: lot 168 Form in advance of the sale. The Friday November 2, Please contact client services with Session page 4: lot 192 form can be found at the back of 10am to 5pm any bidding inquiries. Session page 5: lot 267 every catalogue and on our Saturday November 3, Session page 6: lot 263 website at www.bonhams.com and 12pm to 5pm Please see pages 152 to 155 Session page 7: lot 398 should be returned by email or Sunday November 4, for bidder information including Session page 8: lot 416 post to the specialist department 12pm to 5pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale Session page 9: lot 466 or to the bids department at collection and shipment. -

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? and Involved an Axelrod-Like Writer, a Monroe-Like Star, and a Satanic Agent Who Collected Percentages of Souls Rather Than Salaries

The American Century Theater presents by George Axelrod Audience Guide Written and compiled by Jack Marshall January 15–February 6 Theatre II, Gunston Arts Center Theater you can afford to seesee———— ppplaysplays you can’t afford to miss! About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, and neglected American plays of the twentieth century . what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender our moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. These audience guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. The American Century Theater is a 501(c)(3) professional nonprofit theater company dedicated to producing significant 20th Century American plays and musicals at risk of being forgotten. The American Century Theater is supported in part by Arlington County through the Cultural Affairs Division of the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources and the Arlington Commission for the Arts. This arts event is made possible in part by the Virginia Commission on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as by many generous donors. -

Dopo Pino Daniele, Rosi E Anita Ekberg<!--:-->

Dipartite: dopo Pino Daniele, Rosi e Anita Ekberg Ci sono immagini, suoni e parole che rimarranno impresse nella mente di milioni di persone,poiché chi le ha interpretate le ha rese eterne. Il 2014 ha portato via con sé personalità conosciute tra cui il cantante Giuseppe Mango, morto stroncato da un infarto, durante il concerto che stava tenendo al Pala Ercole di Policoro, in provincia di Matera, gli attori americani Robin Williams e Philip Seymour Hoffman, il premio nobel per la letteratura Gabriel García Márquez,La bimba prodigio di Hollywood Shirley Temple, e l’attrice nazionalpopolare Virna Lisi. Il 2015 non ha compiuto il suo primo “complemese”, ma ha già visto tre importanti personaggi di fama mondiale spegnersi lasciando in chi li ha sempre sostenuti e amati un vuoto incolmabile caratterizzato da grande incredulità,perché alcune persone sembrano immortali. Il 4 gennaio, il cantautore partenopeo Pino Daniele che attraverso canzoni come Napule ha reso onore alla sua città è stato stroncato da un infarto. Il 10 gennaio è deceduto il regista Francesco Rosi, profondo innovatore del linguaggio cinematografico e fautore di un grande impegno sociale e politico, ha prodotto film quali: Il caso Mattei e Le mani sulla città. Il suo operato ha ispirato registi del calibro di Coppola e Scorsese. Esemplare e degna di rispetto è stata l’iniziativa promossa dalla figlia di Rosi, Carolina che ha invitato sostenitori e amici attraverso il suo necrologio pubblicato sul quotidiano “Il Corriere della sera” a non rendere omaggio a suo padre mediante dei fiori, ma con “la solidarietà agli immigrati”. Dopo sole ventiquattro ore si è spenta Anita Ekberg, meglio conosciuta come la femme fatale dalla chioma color oro che con andatura elegante interpretò la scena girata nella fontana di Trevi del film “La Dolce Vita” di Federico Fellini. -

Ebay: 1000+ Vinyl RECORD COLLECTION-Soundtrack-Cast-TV-Hippie (Item 4856976553 End Time Apr-03-06 15:37:28 PDT) 03/31/2006 08:31 AM

eBay: 1000+ Vinyl RECORD COLLECTION-Soundtrack-Cast-TV-Hippie (item 4856976553 end time Apr-03-06 15:37:28 PDT) 03/31/2006 08:31 AM home | pay | register | sign out | site map Start new search Search Advanced Search Back to My eBay Listed in category: Music > Records 1000+ Vinyl RECORD COLLECTION-Soundtrack-Cast-TV-Hippie Item number: 4856976553 Beatnik, Kids, Personality, Sexy, Sports-Vogues, Promo You are signed in Meet the seller justkidsnostalgia ( 9127 ) Current bid: US $17,600.00 Place Bid > Seller: Feedback: 99.5% Positive Reserve not met Member: since Apr-15-99 in United States No payments for 3 months - Apply now Read feedback comments Ask seller a question Add to Favorite Sellers End time: Apr-03-06 15:37:28 PDT (3 days 9 hours) View seller's other items Shipping costs: Check item description and payment instructions or contact seller for details Buy safely Ships to: Worldwide 1. Check the seller's reputation Item location: Huntington, NY, United States Score: 9127 | 99.5% Positive History: 8 bids Read feedback comments 2. Learn how you are protected High bidder: skipper51 ( 12477 ) Free PayPal Buyer Protection. See eligibility View larger picture You can also: Watch this item Email to a friend Listing and payment details: Show Description (revised) Item Specifics - Music: Records Speed: -- Genre: Soundtrack, Theater Record Size: -- Sub-Genre: -- Duration: -- Just Kids Nostalgia is now listing a very large collection of personality records. The Weird, The Unusual, The Interesting, The Oddball... Over 1,000 Records! Rare Movie Soundtracks… Myra Breckenridge staring Mae West, God’s Little Acre, Hercules, On A Note of Triumph, Silencers Interview Record with Dean Martin, Single Room Furnished with Jane Mansfield, From Here to Eternity 10”, The Girl in the Bikini with Bardot.