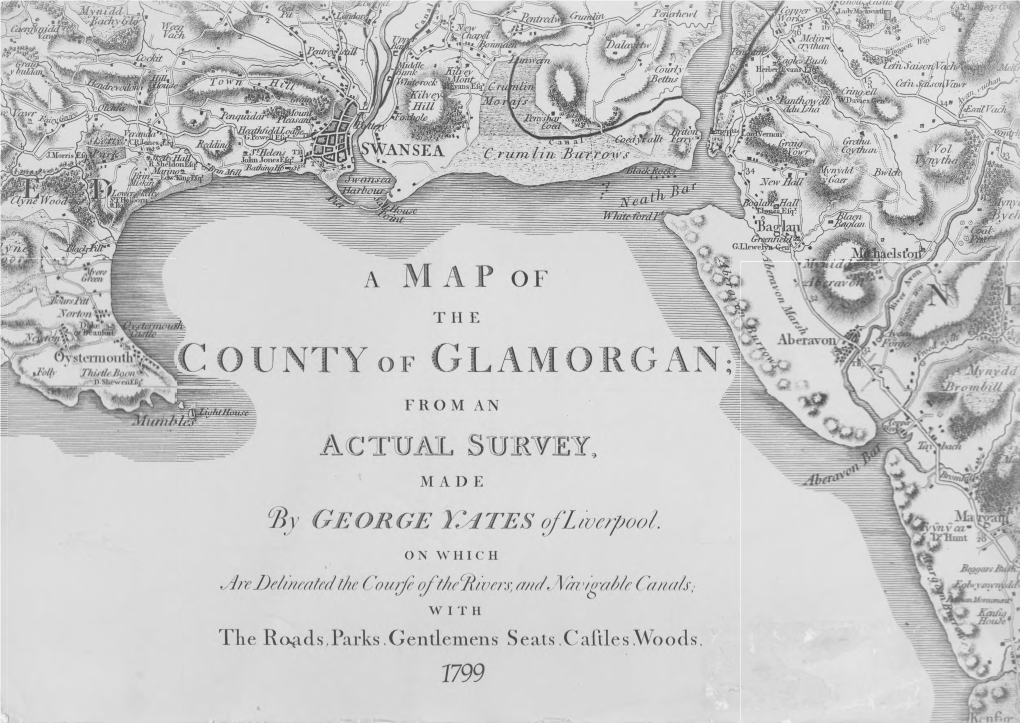

Yates' Map of Glamorgan 1799

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX 2 EXTRACT of REVIEW REPORT – POSITION STATEMENT on JOINT REVIEW Caerphilly County Borough Council Local Development

APPENDIX 2 EXTRACT OF REVIEW REPORT – POSITION STATEMENT ON JOINT REVIEW Caerphilly County Borough Council Local Development Plan – First Review Caerphilly County Borough Council adopted its LDP in November 2010 and has since been monitoring the progress of the plan through its Annual Monitoring Report (AMR). As a consequence of the findings of the 2013 AMR, the Council resolved to trigger the first full review of the plan in line with LDP Regulation 41. There is no specific guidance on the review process, other than that contained in the Local Development Plan (Wales) Regulations 2005. Procedures for consultation and handling representations on LDP alterations are set out in LDP Wales, paras 4.46 – 4.50. As part of the early stakeholder engagement for the review, a series of stakeholder events has occurred. As a consequence of WG involvement in this process Caerphilly County Borough Council has been advised that appropriate consideration should be given to preparing a Joint LDP with neighbouring authorities, particularly in light of the proposals contained within the Positive Planning Consultation Paper and Draft Planning Bill as outlined above. Consideration has been given to the preparation of a joint review with Torfaen and Blaenau Gwent Councils reflecting the recommendations contained within the Williams Report. This indicates that Caerphilly, Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen could be merged into a single local planning authority. At its meeting on the 29 September 2014, the Council resolved that Caerphilly County Borough Council does not support the idea of a merged authority covering Caerphilly, Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen. The preparation of a joint LDP review does not however require the formal merger of the Councils in question to enable this work to be undertaken. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Handbook to Cardiff and the Neighborhood (With Map)

HANDBOOK British Asscciation CARUTFF1920. BRITISH ASSOCIATION CARDIFF MEETING, 1920. Handbook to Cardiff AND THE NEIGHBOURHOOD (WITH MAP). Prepared by various Authors for the Publication Sub-Committee, and edited by HOWARD M. HALLETT. F.E.S. CARDIFF. MCMXX. PREFACE. This Handbook has been prepared under the direction of the Publications Sub-Committee, and edited by Mr. H. M. Hallett. They desire me as Chairman to place on record their thanks to the various authors who have supplied articles. It is a matter for regret that the state of Mr. Ward's health did not permit him to prepare an account of the Roman antiquities. D. R. Paterson. Cardiff, August, 1920. — ....,.., CONTENTS. PAGE Preface Prehistoric Remains in Cardiff and Neiglibourhood (John Ward) . 1 The Lordship of Glamorgan (J. S. Corbett) . 22 Local Place-Names (H. J. Randall) . 54 Cardiff and its Municipal Government (J. L. Wheatley) . 63 The Public Buildings of Cardiff (W. S. Purchox and Harry Farr) . 73 Education in Cardiff (H. M. Thompson) . 86 The Cardiff Public Liljrary (Harry Farr) . 104 The History of iNIuseums in Cardiff I.—The Museum as a Municipal Institution (John Ward) . 112 II. —The Museum as a National Institution (A. H. Lee) 119 The Railways of the Cardiff District (Tho^. H. Walker) 125 The Docks of the District (W. J. Holloway) . 143 Shipping (R. O. Sanderson) . 155 Mining Features of the South Wales Coalfield (Hugh Brajiwell) . 160 Coal Trade of South Wales (Finlay A. Gibson) . 169 Iron and Steel (David E. Roberts) . 176 Ship Repairing (T. Allan Johnson) . 182 Pateift Fuel Industry (Guy de G. -

Download the Catalogue

Five Hundred Years of Fine, Fancy and Frivolous Bindings George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK Tel: 01225 466000 • Fax: 01225 482122 Email: [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com BOUND BY BROCA 1. AINSWORTH (William Harrison). The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. 20 engraved plates by George Cruikshank. First Edition. Three volumes. 8vo. [198 x 120 x 66 mm]. vii, [i], 296 pp; iv, 291 pp; iv, 311 pp. Bound c.1900 by L. Broca (signed on the front endleaves) in half red goatskin, marbled paper sides, the spines divided into six panels with gilt compartments, lettered in the second and third and dated at the foot, the others tooled with a rose and leaves on a dotted background, marbled endleaves, top edges gilt. (The paper sides slightly rubbed). [ebc2209]. London: [by T. C. Savill for] Cunningham and Mortimer, 1842. £750 A fine copy in a very handsome binding. Lucien Broca was a Frenchman who came to London to work for Antoine Chatelin, and from 1876 to 1889 he was in partnership with Simon Kaufmann. From 1890 he appears under his own name in Shaftesbury Avenue, and in 1901 he was at Percy Street, calling himself an "Art Binder". He was recognised as a superb trade finisher, and Marianne Tidcombe has confirmed that he actually executed most of Sarah Prideaux's bindings from the mid-1890s. Circular leather bookplate of Alexander Lawson Duncan of Jordanstone House, Perthshire. STENCILLED CALF 2. AKENSIDE (Mark). The Poems. Fine mezzotint frontispiece portrait by Fisher after Pond. First Collected Edition. 4to. [300 x 240 x 42 mm]. -

The Preserved Counties (Amendment to Boundaries) (Wales) Order 2003

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2003 No. 974 (W.133) LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WALES The Preserved Counties (Amendment to Boundaries) (Wales) Order 2003 Made - - - - 1st April 2003 Coming into force - - 2nd April 2003 The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales reported in November 2002 in a “Review of Preserved County Boundaries”. The National Assembly for Wales, having agreed with the proposals, makes the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred on it by section 58(2) of the Local Government Act 1972(1). Title, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order is called The Preserved Counties (Amendment to Boundaries) (Wales) Order 2003 and comes into force on 2nd April 2003. (2) This Order applies to Wales only. Amendment of Preserved County Boundaries 2. The Preserved County boundaries between Clwyd and Gwynedd, South Glamorgan and Mid Glamorgan, and Gwent and Mid Glamorgan are revised such that the areas of those Preserved Counties are as described in Article 3. New Preserved County Boundaries 3.—(1) The Preserved County of Clwyd comprises the areas of the counties and county boroughs of Denbighshire, Flintshire, Wrexham and Conwy. (2) The Preserved County of Gwynedd comprises the areas of the counties of Anglesey and Gwynedd. (3) The Preserved County of Gwent comprises the areas of the counties and county boroughs of Monmouthshire, Blaenau Gwent, Torfaen, Newport and Caerphilly. (4) The Preserved County of Mid Glamorgan comprises the areas of the county boroughs of Bridgend, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhondda Cynon Taff. -

Railway and Canal Historical Society Early Railway Group

RAILWAY AND CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY EARLY RAILWAY GROUP Occasional Paper 251 BENJAMIN HALL’S TRAMROADS AND THE PROMOTION OF CHAPMAN’S LOCOMOTIVE PATENT Stephen Rowson, with comment from Andy Guy Stephen Rowson writes - Some year ago I had access to some correspondence originally in the Llanover Estate papers and made this note from within a letter by Benjamin Hall to his agent John Llewellin, dated 7 March 1815: Chapman the Engineer called on me today. He says one of their Engines will cost about £400 & 30 G[uinea]s per year for his Patent. He gave a bad account of the Collieries at Newcastle, that they do not clear 5 per cent. My original thoughts were of Chapman looking for business by hawking a working model of his locomotive around the tramroads of south Wales until I realised that Hall wrote the letter from London. So one assumes the meeting with William Chapman had taken place in the city rather than at Hall’s residence in Monmouthshire. No evidence has been found that any locomotive ran on Hall’s Road until many years later after it had been converted from a horse-reliant tramroad. Did any of Chapman’s locomotives work on south Wales’ tramroads? __________________________________ Andy Guy comments – This is a most interesting discovery which raises a number of issues. In 1801, Benjamin Hall, M.P. (1778-1817) married Charlotte, daughter of the owner of Cyfarthfa ironworks, Richard Crawshay, and was to gain very considerable industrial interests from his father- in-law.1 Hall’s agent, John Llewellin, is now better known now for his association with the Trevithick design for the Tram Engine, the earliest surviving image of a railway locomotive.2 1 Benjamin Hall was the son of Dr Benjamin Hall (1742–1825) Chancellor of the diocese of Llandaff, and father of Sir Benjamin Hall (1802-1867), industrialist and politician, supposedly the origin of the nickname ‘Big Ben’ for Parliament’s clock tower (his father was known as ‘Slender Ben’ in Westminster). -

Devolution Decade

spring 2009 Production Editor: John Osmond Devolution Decade Assistant Editor: Nick Morris Associate Editors: On the face of it the verdicts we publish in this issue by leading protagonists in Geraint Talfan Davies, Rhys David the 1997 referendum on the first ten years of the National Assembly make pretty depressing reading. Professor Kevin Morgan, who chaired the Yes Campaign, is Administration: Helen Sims-Coomber, Clare Johnson especially damning. He lets us in to what he describes as “devolution’s dirty little secret”, its failure to make a fist of developing the Welsh economy. And the Design: statistics are incontrovertible. In terms of our prosperity relative to most other www.theundercard.co.uk parts of the United Kingdom, we’ve actually gone backwards in the first decade To advertise – declining from 77 to 75 per cent of the UK’s average GVA. When we started Tel: 029 2066 6606 out the Assembly Government’s stated ambition was to climb to 90 per cent by Institute of Welsh Affairs 2010, an aspiration that has been quietly dropped. One way or another our other 4 Cathedral Road contributors all point to the economy as the central reason for their Cardiff CF11 9LJ disappointment with devolution’s record so far. Tel: 029 2066 0820 Yet a narrow focus on the economy, important as it undoubtedly is, leads Email: [email protected] to a zero sum game. Devolution is about much more than that. And anyway, www.iwa.org.uk as Kevin Morgan himself concedes, the amount that government can do to The IWA is a non-aligned independent think- influence the economy will always be limited, especially a government with so tank and research institute, based in Cardiff with relatively little control over the main economic levers as the one in Cardiff Bay. -

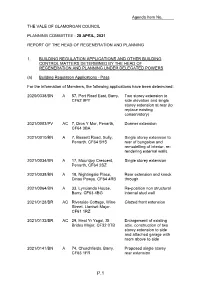

Planning Committee Report 20-04-21

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 28 APRIL, 2021 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2020/0338/BN A 57, Port Road East, Barry. Two storey extension to CF62 9PY side elevation and single storey extension at rear (to replace existing conservatory) 2021/0003/PV AC 7, Dros Y Mor, Penarth, Dormer extension CF64 3BA 2021/0010/BN A 7, Bassett Road, Sully, Single storey extension to Penarth. CF64 5HS rear of bungalow and remodelling of interior, re- rendering external walls. 2021/0034/BN A 17, Mountjoy Crescent, Single storey extension Penarth, CF64 2SZ 2021/0038/BN A 18, Nightingale Place, Rear extension and knock Dinas Powys. CF64 4RB through 2021/0064/BN A 33, Lyncianda House, Re-position non structural Barry. CF63 4BG internal stud wall 2021/0128/BR AC Riverside Cottage, Wine Glazed front extension Street, Llantwit Major. CF61 1RZ 2021/0132/BR AC 29, Heol Yr Ysgol, St Enlargement of existing Brides Major, CF32 0TB attic, construction of two storey extension to side and attached garage with room above to side 2021/0141/BN A 74, Churchfields, Barry. Proposed single storey CF63 1FR rear extension P.1 2021/0145/BN A 11, Archer Road, Penarth, Loft conversion and new CF64 3HW fibre slate roof 2021/0146/BN A 30, Heath Avenue, Replace existing beam Penarth. -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Vale of Glamorgan Profile (Final Version at March 2017)

A profile of the Vale of Glamorgan The Vale of Glamorgan is a diverse and beautiful part of Wales. The county is characterised by rolling countryside, coastal communities, busy towns and rural villages but also includes Cardiff Airport, a variety of industry and businesses and Wales’s largest town. The area benefits from good road and rail links and is well placed within the region as an area for employment as a visitor destination and a place to live. The map below shows some key facts about the Vale of Glamorgan. There are however areas of poverty and deprivation and partners are working with local communities to ensure that the needs of different communities are understood and are met, so that all residents can look forward to a bright future. Our population The population of the Vale of Glamorgan as per 2015 mid-year estimates based on 2011 Census data was just under 128,000. Of these, approximately 51% are female and 49% male. The Vale has a similar age profile of population as the Welsh average with 18.5% of the population aged 0-15, 61.1% aged 16-64 and 20.4% aged 65+. Population projections estimate that by 2036 the population aged 0-15 and aged 16-64 will decrease. The Vale also has an ageing population with the number of people aged 65+ predicted to significantly increase and be above the Welsh average. 1 Currently, the percentage of the Vale’s population reporting activity limitations due to a disability is one of the lowest in Wales. -

Deposit Draft Local Development Plan 2006 - 2021 Preserving Our Heritage • Building Our Future Contents

Deposit Draft Local Development Plan 2006 - 2021 Preserving Our Heritage • Building Our Future Contents Chapter 1 Introduction and Context ......................................3 Chapter 7 Monitoring and Review Framework....................117 Introduction...................................................................3 Appendix 1 Detailed Allocations ..........................................121 Structure of document ..................................................4 a) Housing Allocations .............................................121 Key facts about Rhondda Cynon Taf.............................5 b) Employment Allocations......................................128 Links to other Strategies................................................5 c) Retail Allocations .................................................130 National Planning Policy and Technical Advice.........11 d) Major Highway Schemes......................................131 How to use the document...........................................15 e) Sites of Important Nature Conservation Chapter 2 Key Issues in Rhondda Cynon Taf .........................17 and Local Nature Reserves ..................................133 Chapter 3 Vision and Objectives ..........................................21 Appendix 2 Statutory Designations.......................................137 Chapter 4 Core Strategy.......................................................25 Appendix 3 Local Development Plan Evidence Base..............139 Key Diagram ................................................................28 -

Parc Afon Ewenni Regeneration Area MASTERPLAN FRAMEWORK and DELIVERY STRATEGY

Parc Afon Ewenni Regeneration Area MASTERPLAN FRAMEWORK AND DELIVERY STRATEGY NOVEMBER 2011 Contents SECTION 1 Introduction 4 SECTION 2 Vision and objectives 7 SECTION 3 Site and contextual analysis 9 SECTION 4 Planning Policy context 19 SECTION 5 Challenges and opportunities 24 SECTION 6 Development framework 26 SECTION 7 Delivery strategy 44 SECTION 8 Summary and Conclusions 50 Parc Afon Ewenni Regeneration Area MASTERPLAN FRAMEWORK AND DELIVERY STRATEGY Contents 3 1 1. Introduction The Commission The Client Group Framework Masterplan This Framework Masterplan has been prepared by Savills in The Client Group consists of the following parties: This Framework Masterplan revisits the previous Masterplan conjunction with Waterman Transport and Development. It WRUHÁHFWWKLVHFRQRPLFFKDQJHDQGUHYLHZVWKHVWUDWHJ\IRU outlines the aspirations for future development of land at Bridgend County Borough Council (BCBC) WKHDUHDLGHQWLI\LQJWKHIXWXUHRSSRUWXQLWLHVDQGKRZWKH :DWHUWRQ5RDGLQ%ULGJHQGDOVRNQRZQDVWKH3DUF$IRQ South Wales Police (SWP) development potential of the area can be realised. Ewenni Regeneration Area. Dovey Estates Ltd (DEL) The production of this Framework Masterplan for the BCBC The initial brief of the commission was to prepare a Framework Waterton Depot allows for a planned approach to future 0DVWHUSODQYLVLRQDQGVWUDWHJ\IRUWKHZKROHVLWHDUHDDQG Previous ‘Parc Afon Ewenni’ Masterplanning Work development and inward investment and would link into the a linked Development Brief of the BCBC Waterton Depot emerging Local Development Plan (LDP) which is currently VLWHWKDWHQFRXUDJHVIRUDPRUHSODQQHGDSSURDFKWRWKH Powell Dobson Urbanists were appointed by BCBC and the being prepared for the County Borough. future development of the area. The brief emphasised that the Welsh Government in 2006 to prepare a masterplan for part of commercial viability of potential development was an integral WKHVLWHZKLFKZDVNQRZQDV¶3DUF$IRQ(ZHQQL·+RZHYHUWKH Achieving sustainable and deliverable development and good part of the exercise.