Praying Mantis (Stagmomantis Californica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

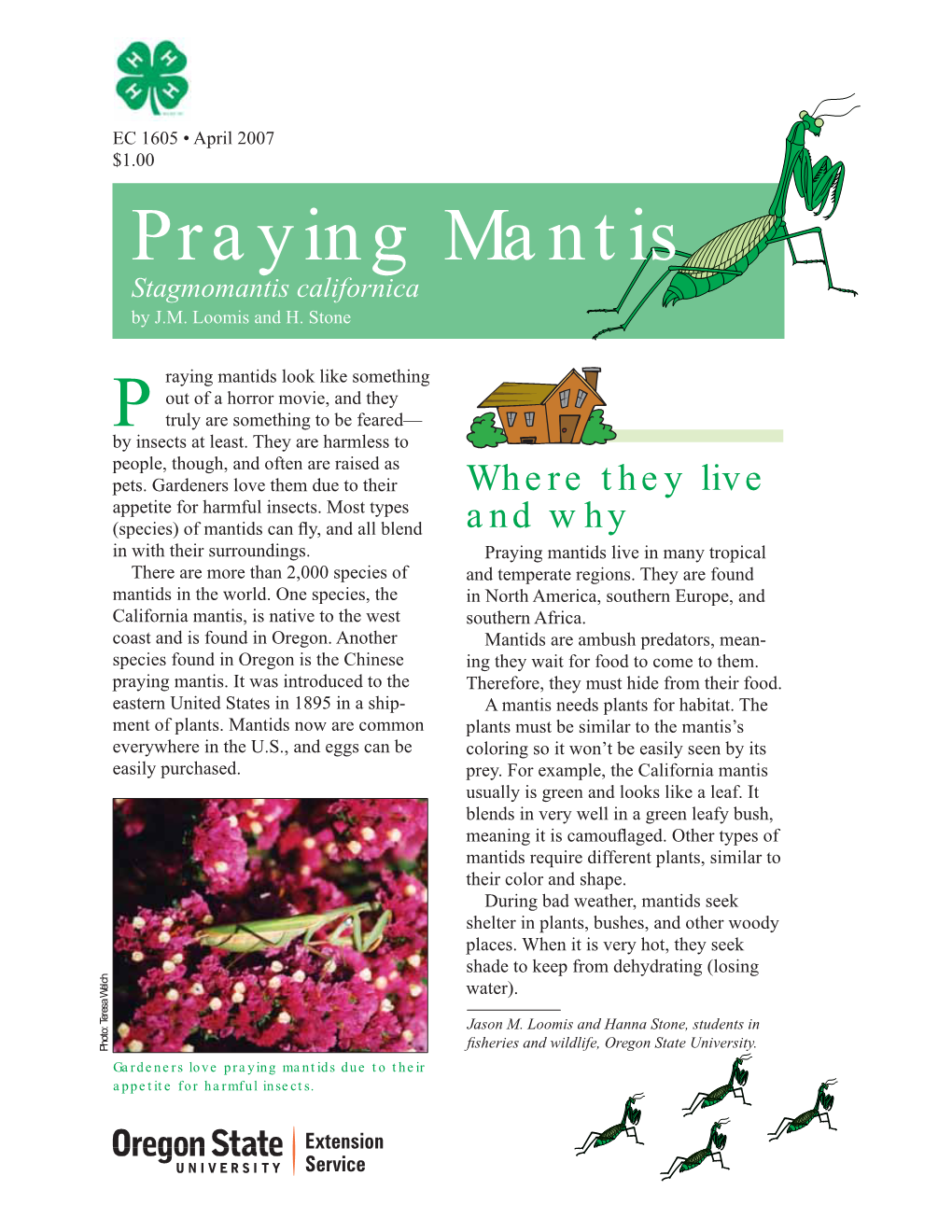

Recommended publications

-

The Buzz About Bees: Honey Bee Biology and Behavior

4-H Honey Bee Leaders Guide Book I The Buzz About Bees: 18 U.S.C. 707 Honey Bee Biology and Behavior Publication 380-071 2009 To the 4-H Leader: The honey bee project (Books Grade 5 1 - 4) is intended to teach young people the basic biology and behavior of honey bees in addition to Living Systems 5.5 hands-on beekeeping management skills. The honey The student will investigate and understand that bee project books begin with basic honey bee and organisms are made up of cells and have distin- insect information (junior level) and advance to guishing characteristics. Key concepts include: instruction on how to rear honey bee colonies and • vertebrates and invertebrates extract honey (senior level). These project books are intended to provide in-depth information related Grade 6 to honey bee management, yet they are written for the amateur beekeeper, who may or may not have Life Science 5 previous experience in rearing honey bees. The student will investigate and understand how organisms can be classified. Key concepts include: Caution: • characteristics of the species If anyone in your club is known to have severe Life Science 8 allergic reactions to bee stings, they should not The student will investigate and understand that participate in this project. interactions exist among members of a population. The honey bee project meets the following Vir- Key concepts include: ginia State Standards of Learning (SOLs) for the • competition, cooperation, social hierarchy, and fourth, fifth, and sixth grades: territorial imperative Grade 4 Acknowledgments Authors: Life Processes 4.4 Dini M. -

Wisconsin Bee Identification Guide

WisconsinWisconsin BeeBee IdentificationIdentification GuideGuide Developed by Patrick Liesch, Christy Stewart, and Christine Wen Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) The honey bee is perhaps our best-known pollinator. Honey bees are not native to North America and were brought over with early settlers. Honey bees are mid-sized bees (~ ½ inch long) and have brownish bodies with bands of pale hairs on the abdomen. Honey bees are unique with their social behavior, living together year-round as a colony consisting of thousands of individuals. Honey bees forage on a wide variety of plants and their colonies can be useful in agricultural settings for their pollination services. Honey bees are our only bee that produces honey, which they use as a food source for the colony during the winter months. In many cases, the honey bees you encounter may be from a local beekeeper’s hive. Occasionally, wild honey bee colonies can become established in cavities in hollow trees and similar settings. Photo by Christy Stewart Bumble bees (Bombus sp.) Bumble bees are some of our most recognizable bees. They are amongst our largest bees and can be close to 1 inch long, although many species are between ½ inch and ¾ inch long. There are ~20 species of bumble bees in Wisconsin and most have a robust, fuzzy appearance. Bumble bees tend to be very hairy and have black bodies with patches of yellow or orange depending on the species. Bumble bees are a type of social bee Bombus rufocinctus and live in small colonies consisting of dozens to a few hundred workers. Photo by Christy Stewart Their nests tend to be constructed in preexisting underground cavities, such as former chipmunk or rabbit burrows. -

Phylum Arthropod Silvia Rondon, and Mary Corp, OSU Extension Entomologist and Agronomist, Respectively Hermiston Research and Extension Center, Hermiston, Oregon

Phylum Arthropod Silvia Rondon, and Mary Corp, OSU Extension Entomologist and Agronomist, respectively Hermiston Research and Extension Center, Hermiston, Oregon Member of the Phyllum Arthropoda can be found in the seas, in fresh water, on land, or even flying freely; a group with amazing differences of structure, and so abundant that all the other animals taken together are less than 1/6 as many as the arthropods. Well-known members of this group are the Kingdom lobsters, crayfish and crabs; scorpions, spiders, mites, ticks, Phylum Phylum Phylum Class the centipedes and millipedes; and last, but not least, the Order most abundant of all, the insects. Family Genus The Phylum Arthropods consist of the following Species classes: arachnids, chilopods, diplopods, crustaceans and hexapods (insects). All arthropods possess: • Exoskeleton. A hard protective covering around the outside of the body (divided by sutures into plates called sclerites). An insect's exoskeleton (integument) serves as a protective covering over the body, but also as a surface for muscle attachment, a water-tight barrier against desiccation, and a sensory interface with the environment. It is a multi-layered structure with four functional regions: epicuticle (top layer), procuticle, epidermis, and basement membrane. • Segmented body • Jointed limbs and jointed mouthparts that allow extensive specialization • Bilateral symmetry, whereby a central line can divide the body Insect molting or removing its into two identical halves, left and right exoesqueleton • Ventral nerve -

Biological Pest Control

■ ,VVXHG LQ IXUWKHUDQFH RI WKH &RRSHUDWLYH ([WHQVLRQ :RUN$FWV RI 0D\ DQG -XQH LQ FRRSHUDWLRQ ZLWK WKH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV 'HSDUWPHQWRI$JULFXOWXUH 'LUHFWRU&RRSHUDWLYH([WHQVLRQ8QLYHUVLW\RI0LVVRXUL&ROXPELD02 ■DQHTXDORSSRUWXQLW\$'$LQVWLWXWLRQ■■H[WHQVLRQPLVVRXULHGX AGRICULTURE Biological Pest Control ntegrated pest management (IPM) involves the use of a combination of strategies to reduce pest populations Steps for conserving beneficial insects Isafely and economically. This guide describes various • Recognize beneficial insects. agents of biological pest control. These strategies include judicious use of pesticides and cultural practices, such as • Minimize insecticide applications. crop rotation, tillage, timing of planting or harvesting, • Use selective (microbial) insecticides, or treat selectively. planting trap crops, sanitation, and use of natural enemies. • Maintain ground covers and crop residues. • Provide pollen and nectar sources or artificial foods. Natural vs. biological control Natural pest control results from living and nonliving Predators and parasites factors and has no human involvement. For example, weather and wind are nonliving factors that can contribute Predator insects actively hunt and feed on other insects, to natural control of an insect pest. Living factors could often preying on numerous species. Parasitic insects lay include a fungus or pathogen that naturally controls a pest. their eggs on or in the body of certain other insects, and Biological pest control does involve human action and the young feed on and often destroy their hosts. Not all is often achieved through the use of beneficial insects that predacious or parasitic insects are beneficial; some kill the are natural enemies of the pest. Biological control is not the natural enemies of pests instead of the pests themselves, so natural control of pests by their natural enemies; host plant be sure to properly identify an insect as beneficial before resistance; or the judicious use of pesticides. -

Colour Transcript

Colour Transcript Date: Wednesday, 30 March 2011 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 30 March 2011 Colour Professor William Ayliffe Some of you in this audience will be aware that it is the 150th anniversary of the first colour photograph, which was projected at a lecture at the Royal Institute by James Clerk Maxwell. This is the photograph, showing a tartan ribbon, which was taken using the first SLR, invented by Maxwell’s friend. He took three pictures, using three different filters, and was then able to project this gorgeous image, showing three different colours for the first time ever. Colour and Colour Vision This lecture is concerned with the questions: “What is colour?” and “What is colour vision?” - not necessarily the same things. We are going to look at train crashes and colour blindness (which is quite gruesome); the antique use of colour in pigments – ancient red Welsh “Ladies”; the meaning of colour in medieval Europe; discovery of new pigments; talking about colour; language and colour; colour systems and the psychology of colour. So there is a fair amount of ground to cover here, which is appropriate because colour is probably one of the most complex issues that we deal with. The main purpose of this lecture is to give an overview of the whole field of colour, without going into depth with any aspects in particular. Obviously, colour is a function of light because, without light, we cannot see colour. Light is that part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can see, and that forms only a tiny portion. -

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear(Isabella Tiger Moth Larva)

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear (Isabella Tiger Moth larva) basics The banded woollybear gets its name for two reasons: its furry appearance and the fact that, like a bear, it hibernates during the winter. Woollybears are the caterpillar stage of medium sized moths known as tiger moths. This family of moths rivals butterflies in beauty and grace. There are approximately 260 species of tiger moths in North America. Though the best-known woollybear is the banded woollybear, there are at least 8 woollybear species in the U.S. with similar dense, bristly hair covering their bodies. Woollybears are most commonly seen in the autumn, when they are just about finished with feeding for the year. It is at this time that they seek out a place to spend the winter in hibernation. They have been eating various green plants since June or early July to gather enough energy for their eventual transformation into butterflies. A full-grown banded woollybear caterpillar is nearly two inches long and covered with tubercles from which arise stiff hairs of about equal length. Its body has 13 segments. Middle segments are covered with red-orange hairs and the anterior and posterior ends with black hairs. The orange-colored oblongs visible between the tufts of setae (bristly hairs) are spiracles—entrances to the respiratory system. Hair color and band width are highly variable; often as the caterpillar matures, black hairs (especially at the posterior end) are replaced with orange hairs. In general, older caterpillars have more black than young ones. However, caterpillars that fed and grew in an area where the fall weather was wetter tend to have more black hair than caterpillars from dry areas. -

Lesson 3 Life Cycles of Insects

Praying Mantis 3A-1 Hi, boys and girls. It’s time to meet one of the most fascinating insects on the planet. That’s me. I’m a praying mantis, named for the way I hold my two front legs together as though I am praying. I might look like I am praying, but my incredibly fast front legs are designed to grab my food in the blink of an eye! Praying Mantis 3A-1 I’m here to talk to you about the life stages of insects—how insects develop from birth to adult. Many insects undergo a complete change in shape and appearance. I’m sure that you are already familiar with how a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The name of the process in which a caterpillar changes, or morphs, into a butterfly is called metamorphosis. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 Insects like the butterfly pass through four stages in their life cycles: egg, larva [LAR-vah], pupa, and adult. Each stage looks completely different from the next. The young never resemble, or look like, their parents and almost always eat something entirely different. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 The female insect lays her eggs on a host plant. When the eggs hatch, the larvae [LAR-vee] that emerge look like worms. Different names are given to different insects in this worm- like stage, and for the butterfly, the larva state is called a caterpillar. Insect larvae: maggot, grub and caterpillar3A-3 Fly larvae are called maggots; beetle larvae are called grubs; and the larvae of butterflies and moths, as you just heard, are called caterpillars. -

The Effects of Native and Non-Native Grasses on Spiders, Their Prey, and Their Interactions

Spiders in California’s grassland mosaic: The effects of native and non-native grasses on spiders, their prey, and their interactions by Kirsten Elise Hill A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Professor Rosemary G. Gillespie Professor Mary E. Power Spring 2014 © 2014 Abstract Spiders in California’s grassland mosaic: The effects of native and non-native grasses on spiders, their prey, and their interactions by Kirsten Elise Hill Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science and Policy Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Joe R. McBride, Chair Found in nearly all terrestrial ecosystems, small in size and able to occupy a variety of hunting niches, spiders’ consumptive effects on other arthropods can have important impacts for ecosystems. This dissertation describes research into spider populations and their interactions with potential arthropod prey in California’s native and non-native grasslands. In meadows found in northern California, native and non-native grassland patches support different functional groups of arthropod predators, sap-feeders, pollinators, and scavengers and arthropod diversity is linked to native plant diversity. Wandering spiders’ ability to forage within the meadow’s interior is linked to the distance from the shaded woodland boundary. Native grasses offer a cooler conduit into the meadow interior than non-native annual grasses during midsummer heat. Juvenile spiders in particular, are more abundant in the more structurally complex native dominated areas of the grassland. -

Insects Carolina Mantis Mayfly

I l l i n o i s Insects Carolina mantis mayfly elephant stag beetle widow skimmer ichneumon wasp click beetle black locust borer birdwing grasshopper large milkweed bug (adults and nymphs) mantisfly walking stick lady beetle stink bug crane fly stonefly (nymph) horse fly wheel bug bot fly prairie cicada leafhopper robber fly katydid alderfly syrphid fly Order Ephemeroptera mayfly Species List Order Coleoptera black locust borer click beetle This poster was made possible by: nsects and their relatives (arthropods) make up nearly 80 percent of the known animal species. Scientists elephant stag beetle lady beetle Illinois Department of Natural Resources Order Plecoptera stonefly currently estimate that 5 to 15 million species of insects exist. In contrast, 5,000 species of mammals are Order Orthoptera birdwing grasshopper Carolina mantis Division of Education found on our planet. In Illinois, we have more than 20,000 species of insects, and many more likely katydid Illinois Natural History Survey I Order Hemiptera large milkweed bug Illinois State Museum occur, as yet undetected in our state! The scientific study of insects is known as entomology. Entomologists stink bug wheel bug Order Diptera bot fly study insects for many reasons, including their incredible number of species and their wide variety of sizes, crane fly horse fly colors, shapes, and lifestyles. The 24 species depicted on this poster were selected by Michael R. Jeffords of robber fly syrphid fly Order Homoptera leafhopper the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Illinois Natural History Survey, to represent the variety of prairie cicada Order Phasmida walking stick insects occurring in our state. -

German Cockroach, Blattella Germanica (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Blattodea: Blattellidae)1 S

EENY-002 doi.org/10.32473/edis-in1283-2020 German Cockroach, Blattella germanica (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Blattodea: Blattellidae)1 S. Valles2 The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of Distribution insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant The German cockroach is found throughout the world to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested in association with humans. They are unable to survive laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as in locations away from humans or human activity. The academic audiences. major factor limiting German cockroach survival appears to be cold temperatures. Studies have shown that German Introduction cockroaches were unable to colonize inactive ships during The German cockroach (Figure 1) is the cockroach of cool temperatures and could not survive in homes without concern, the species that gives all other cockroaches a bad central heating in northern climates. The availability name. It occurs in structures throughout Florida, and is of water, food, and harborage also govern the ability of the species that typically plagues multifamily dwellings. In German cockroaches to establish populations, and limit Florida, the German cockroach may be confused with the growth. Asian cockroach, Blattella asahinai Mizukubo. While these cockroaches are very similar, there are some differences that Description a practiced eye can discern. Egg Eggs are carried in an egg case, or ootheca, by the female until just before hatch occurs. The ootheca can be seen protruding from the posterior end (genital chamber) of the female. Nymphs will often hatch from the ootheca while the female is still carrying it (Figure 2). -

World Ocean Datbase User's Manual

National Oceanographic Data Center Internal Report 22 doi:10.7289/V5DF6P53 WORLD OCEAN DATABASE 2013 USER’S MANUAL Ocean Climate Laboratory National Oceanographic Data Center Silver Spring, Maryland December 24, 2013 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service 1 National Oceanographic Data Center Additional copies of this publication, as well as information about NODC data holdings and services, are available upon request directly from NODC. National Oceanographic Data Center User Services Team NOAA/NESDIS E/OC1 SSMC-3, 4th Floor 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910-3282 Telephone: (301) 713-3277 Fax: (301) 713-3300 E-mail: [email protected] NODC home page: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/ For updates on data, documentation, and additional information about the WOD13 please refer to: http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/WOD/wod_updates.html This document should be cited as: Johnson, D.R., T.P. Boyer, H.E. Garcia, R.A. Locarnini, O.K. Baranova, and M.M. Zweng, 2013. World Ocean Database 2013 User’s Manual. Sydney Levitus, Ed.; Alexey Mishonov, Technical Ed.; NODC Internal Report 22, NOAA Printing Office, Silver Spring, MD, 172 pp. Available at http://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/WOD13/docwod13.html. doi:10.7289/V5DF6P53 2 National Oceanographic Data Center Internal Report 22 doi:10.7289/V5DF6P53 WORLD OCEAN DATABASE 2013 User’s Manual Daphne R. Johnson, Tim P. Boyer, Hernan E. Garcia, Ricardo A. Locarnini, Olga K. Baranova, and Melissa M. Zweng Ocean Climate Laboratory National Oceanographic Data Center Silver Spring, Maryland December 24, 2013 U.S. -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use.