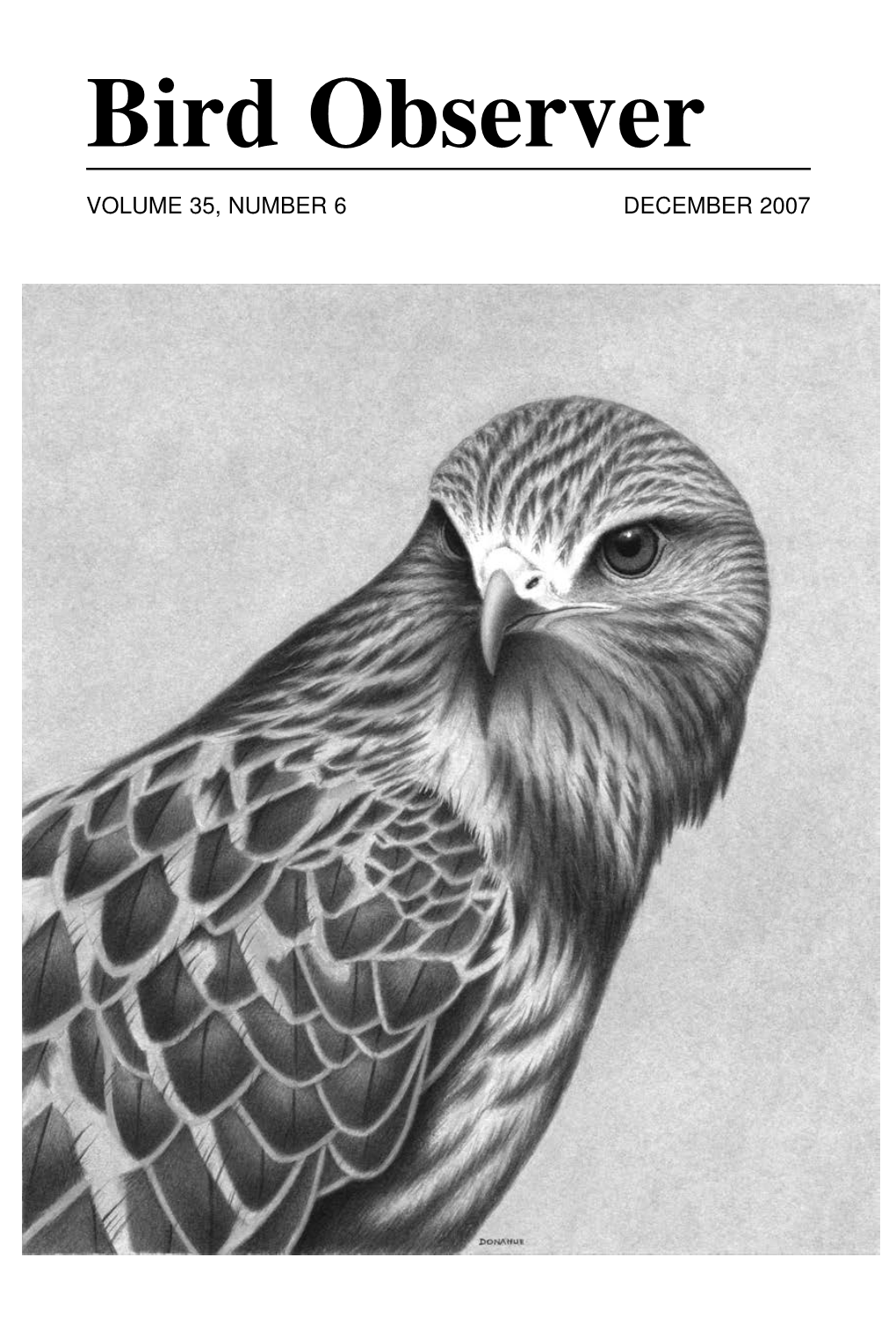

Bird Observer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

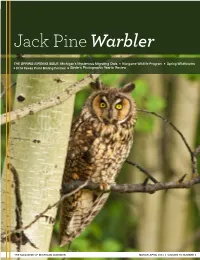

Volume 91 Issue 2 Mar-Apr 2014

Jack Pine Warbler THE SPRING BIRDING ISSUE: Michigan’s Mysterious Migrating Owls Nongame Wildlife Program Spring Wildflowers 2014 Tawas Point Birding Festival Birder’s Photographic Year in Review THE MAGAZINE OF MICHIGAN AUDUBON MARCH-APRIL 2014 | VOLUME 91 NUMBER 2 Cover Photo Long-eared Owl Photographer: Chris Reinhold | [email protected] One day, while taking a drive to a place I normally shoot many hawks and eagles, I came across this Long-eared Owl perched on a fence post. I had heard a number of screeches coming from the CONTACT US area where the owl was hanging out and hunting, so I figured it had By mail: a family of young owls, which it did (four of them). I kept going back PO Box 15249 day after day; I think the owl finally got used to me because I was Lansing, MI 48901 able to get close enough to capture this shot and many others (find them at www.wildartphotography.ca). This image was taken at 1/100 By visiting: sec at f6.3, 500mm focal length, ISO 400 using a stabilized lens and Bengel Wildlife Center Tripod. Gear was a Canon 7D and Sigma 150-500mm lens. 6380 Drumheller Road Bath, MI 48808 Phone 517-641-4277 Fax 517-641-4279 Mon.–Fri. 9 AM–5 PM Contents EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jonathan E. Lutz [email protected] Features Columns Departments STAFF Tom Funke 2 8 1 Conservation Director Michigan's Mysterious A Fine Kettle of Hawks Executive Director’s Letter [email protected] Migratory Owls 2013 Spring Raptor Migration Wendy Tatar 3 Program Coordinator 4 9 Calendar [email protected] Michigan’s Nongame Book Review Wildlife Program Used Books Help Birds 13 Mallory King Announcements Marketing and Communications Coordinator 7 10 New Member List [email protected] Warblers & New Waves in Chapter Spotlight Birding & 2014 Tawas Point Oakland Audubon Society Michael Caterino Birding Festival Membership Assistant 11 [email protected] Spring Wildflowers EDITOR Ephemeral: n. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup Winter 2014 In This Issue: Bioblitz... Lectures... Film Festival... Executive Director’s Report... Festival of Arts... BLM Acting Director’s Visit... Archeology & Heritage Month... Dark Skies Position... Ron Beck’s Big Year... Christmas Bird Count Results... Trees along the 19th-Century River... Brunckow’s Cabin Rehab... EOP Leaders Sought... Walkway Bricks... Operations Committee... Members ... Calendar ... Contacts Save the Date! The morning of April 26, FSPR will hold a Bioblitz (an inventory of the flora and fauna) at various locations in SPRNCA. Stay tuned for details in the coming weeks. FSPR Lectures February & March 20 JoinPawlowski, us on Thursday, Water Sentinels February Program 20 at 7 Coordinatorpm at the Sierra for the Vista Grand Ranger Canyon District Chapter Office, of 4070the Sierra East AvenidaClub, will Saracino, Hereford, for a lecture by Becky Orozco on the Chiracahua Apache. Then, on March 20, Steve discuss ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River; current threats; and the conservation work of the Sentinels within SPRNCA. Learn how to use citizen science, “hands-on” conservation, and advocacy to shape a more-sustainable future for one of the Southwest’s most ecologically significant rivers. Second Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival March 13 & 14 The Friends have been invited to host our second Wild & Scenic Film Festival as part of the 12th annual event that showcases North America’s premier collection of short films on the environment. We have selected 13 films for the evening program for adults that are relevant to many of the issues facing the Southwest. Some will make you smile, some may get you angry, others will have you amazed, but hopefully, all will motivate you to get involved. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP Mount Watatic Reservation – Resource Management Plan References Ashburnham, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 2004-2009. Ashby, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 1999-2004. Clark, Frances (Carex Associates), 1999. Biological Survey of Mt. Watatic Wildlife Management Area and Vicinity. Prepared for Mass. Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Conservation Services. 2000. Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2001. Biomap: Guiding Land Conservation for Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2003. Living Waters: Guiding the Protection of Freshwater Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2004. Species Data and Community Stewardship Information. Grifith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, S.M. Pierson, and C.W. Kiilsgaard. 1994. The Massachusetts Ecological Regions Project. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Publication No.17587-74-6/94-DEP. Johnson, Stephen F. 1995. Ninnuock (The People), The Algonquin People of New England. Bliss Publishing, Marlborough, Mass. Massachusetts Invasive Plant Advisory Group. 2005. Strategic Recommendations for Managing Invasive Plants in Massachusetts. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Stol. 12 NO. 2

•‘j \ " - y E ^ tf -jj ^ ^ p j | %A .~.,.. ,.<•;: ,.0v -^~., v:-,’-' ' •'... : .......... ■l:"'-"4.< «S ife.,.. .1 { ‘. , ‘ 'M* m m m m m m m ...y m ;y StoL.W 12 NO. 2 V"-' . :.... .,.■... '..'/.'iff? ' ' kC'"^ ' BIRD OBSERVER OF EASTERN MASSACHUSETTS APRIL 1984 VOL. 12 NO. 2 President Editorial Board Robert H. Stymeist H. Christian Floyd Treasurer Harriet Hoffman Theodore H. Atkinson Wayne R. Petersen Editor Leif J. Robinson Dorothy R. Arvidson Bruce A. Sorrie Martha Vaughan Production Manager Soheil Zendeh Janet L. Heywood Production Subscription Manager James Bird David E. Lange Denise Braunhardt Records Committee Herman H. D’Entremont Ruth P. Emery, Statistician Barbara Phillips Richard A. Forster, Consultant Shirley Young George W. Gove Field Studies Committee Robert H. Stymeist John W. Andrews, Chairman Lee E. Taylor Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts (USPS 369-850) A bi-monthly publication Volume 12, No. 2 March-April 1984 $8.50 per calendar year, January - December Articles, photographs, letters-to-the-editor and short field notes are welcomed. All material submitted will be reviewed by the editorial board. Correspondence should be sent to: Bird Observer > 462 Trapelo Road POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Belmont, MA 02178 All field records for any given month should be sent promptly and not later than the eighth of the following month to Ruth Emery, 225 Belmont Street, Wollaston, MA 02170. Second class postage is paid at Boston, MA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Subscription to BIRD OBSERVER is based on a calendar year, from January to December, at $8.50 per year. Back issues are available at $7.50 per year or $1.50 per issue. -

Annual Report Table of Contents

University of Massachusetts Lowell Fiscal Year 2015 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS CAMPUS RECREATION AT A GLANCE 2 Our Mission 2 Organizational Chart 3 Year In Review 4 PROGRAMS 5 Intramural Sports 5 Club Sports 7 Group Fitness 9 Personal Training 11 Wellness Programs 13 Outdoor Adventure 15 Bike Shop & Bike Share 17 Youth Programs 19 Community Programs 21 Kayak Center and Boathouse 23 UMass Lowell Campus Recreation is committed to excellence in supporting the development of STUDENT EMPLOYMENT 25 healthier and happier lifestyles. Through experiential education we strive to teach students the importance of exercise and recreational activities in preparation for a productive, balanced and Student Payroll and Staff Demographics 25 rewarding life. We will offer diverse and dynamic recreational programming and facilities in order OPERATIONS 27 to meet the needs of our students and create a fun and connected University Community. Facilities 27 Memberships 29 Risk Management 30 MARKETING & PROMOTIONS 31 Social Media 31 CAMPUS RECREATION ORGANIZATIONAL CHART FY ‘15 YEAR IN REVIEW Campus Recreation had a very successful 2014 – 2015 academic year. For the purposes of this report, Campus Recreation focused on participation as our main indicator of success. A large part of this year’s success can be attributed to the addition of staff and financial support. We have used these resources to better serve and support our students and this is demonstrated through the growth in both participation and programs offered. While we have seen achievement throughout all areas, the following bullets are some of our most notable highlights from this past year. Intramural Sports has seen a dramatic increase in participation over the past three years rising from 3,500 participants to nearly 6,000 this year. -

Sculptors Gallery Proudly Hosts “34,” a Group Exhibition Curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX

!"#$"% #&'()$"*# +,((-*. !"#$%&'"(!) *++, 486 Harrison Ave, Boston,."t ! XXXCPTUPOTDVMQUPSTDPNtCPTUPOTDVMQUPST!ZBIPPDPN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 7, 2015 Exhibition Title: 34 Exhibition Dates: July 22 – August 16, 2015 Artists’ Reception: July 26 from 3 – 5 pm SOWA First Friday Reception: August 7 from 5 – 8 pm Gallery Hours: Wed. – Sun. from 12 – 6 pm (Boston, MA): As a part of the Isles Arts Initiative, a summer long public art series on the Boston Harbor Islands and in venues across Boston, the Boston Sculptors Gallery proudly hosts “34,” a group exhibition curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX. Boston Sculptors Gallery will showcase work inspired by the intrinsic beauty and divergent tales of the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park. “34” is a group exhibition that includes 34 regional artists each responding to one of the 34 Boston Harbor Islands. Each imaginative work will be accompanied by a placard, featuring text from Chris Klein’s Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands, which outlines a brief history of the particular island and will provide additional context for the work itself. The exhibition serves as a physical beacon on land that will be in conversation with the artwork on the harbor. Artists’ work will educate and inspire visitors, sharing unique perspectives and visionary iconography that will demonstrate why the islands’ history is among the most fascinating in our region. About Boston Sculptors: Founded in 1992, Boston Sculptors Gallery is an artist-run organization that presents and promotes innovative, challenging sculpture and installations. It is the only sculptors organization in the United States that maintains its own exhibition space. The organization has presented exhibitions of its sculptors in other venues and countries and occasionally invites Curators to present exhibitions in its gallery in Boston’s South End. -

Geologic Relationships of the Southern Portion of the Boston Basin from the Blue Hills Eastward

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Collection 1-1-1976 Geologic Relationships of the Southern Portion of the Boston Basin from the Blue Hills Eastward Nellis, David A. Hellier, Nancy W. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation Nellis, David A. and Hellier, Nancy W., "Geologic Relationships of the Southern Portion of the Boston Basin from the Blue Hills Eastward" (1976). NEIGC Trips. 243. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/243 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trips A-4 & B-4 GEOLOGIC RELATIONSHIPS OF THE SOUTHERN PORTION OF THE BOSTON BASIN FROM THE BLUE HILLS EASTWARD by David A. Nellis boston State College and Nancy W. Hellier The structural, stratigraphic and petrologic relation ships in the Weymouth and Cohasset quadrangles are the princi ple subjects of this field trip. The Dedham Granodiorite is the oldest rock in this area and varies petrologically from granite to granodiorite to diorite. Overlying the Dedham Grano diorite are the lower Cambrian Weymouth Formation and the Middle Cambrian Braintree Argillite. The intrusive contact between Ordovician Quincy Granite and 3raintree Argillite will be noted. At some locations the Weymouth and Braintree formations are missing and the Dedham Granodiorite is overlain by the Bos ton Bay Group sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Pennsylvanian(?) age.