The Challenge of Dubbing Bird Names: Shifts of Meaning and Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Volume 91 Issue 2 Mar-Apr 2014

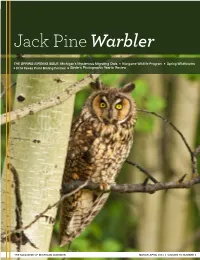

Jack Pine Warbler THE SPRING BIRDING ISSUE: Michigan’s Mysterious Migrating Owls Nongame Wildlife Program Spring Wildflowers 2014 Tawas Point Birding Festival Birder’s Photographic Year in Review THE MAGAZINE OF MICHIGAN AUDUBON MARCH-APRIL 2014 | VOLUME 91 NUMBER 2 Cover Photo Long-eared Owl Photographer: Chris Reinhold | [email protected] One day, while taking a drive to a place I normally shoot many hawks and eagles, I came across this Long-eared Owl perched on a fence post. I had heard a number of screeches coming from the CONTACT US area where the owl was hanging out and hunting, so I figured it had By mail: a family of young owls, which it did (four of them). I kept going back PO Box 15249 day after day; I think the owl finally got used to me because I was Lansing, MI 48901 able to get close enough to capture this shot and many others (find them at www.wildartphotography.ca). This image was taken at 1/100 By visiting: sec at f6.3, 500mm focal length, ISO 400 using a stabilized lens and Bengel Wildlife Center Tripod. Gear was a Canon 7D and Sigma 150-500mm lens. 6380 Drumheller Road Bath, MI 48808 Phone 517-641-4277 Fax 517-641-4279 Mon.–Fri. 9 AM–5 PM Contents EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jonathan E. Lutz [email protected] Features Columns Departments STAFF Tom Funke 2 8 1 Conservation Director Michigan's Mysterious A Fine Kettle of Hawks Executive Director’s Letter [email protected] Migratory Owls 2013 Spring Raptor Migration Wendy Tatar 3 Program Coordinator 4 9 Calendar [email protected] Michigan’s Nongame Book Review Wildlife Program Used Books Help Birds 13 Mallory King Announcements Marketing and Communications Coordinator 7 10 New Member List [email protected] Warblers & New Waves in Chapter Spotlight Birding & 2014 Tawas Point Oakland Audubon Society Michael Caterino Birding Festival Membership Assistant 11 [email protected] Spring Wildflowers EDITOR Ephemeral: n. -

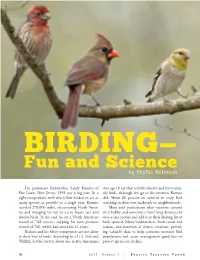

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup Winter 2014 In This Issue: Bioblitz... Lectures... Film Festival... Executive Director’s Report... Festival of Arts... BLM Acting Director’s Visit... Archeology & Heritage Month... Dark Skies Position... Ron Beck’s Big Year... Christmas Bird Count Results... Trees along the 19th-Century River... Brunckow’s Cabin Rehab... EOP Leaders Sought... Walkway Bricks... Operations Committee... Members ... Calendar ... Contacts Save the Date! The morning of April 26, FSPR will hold a Bioblitz (an inventory of the flora and fauna) at various locations in SPRNCA. Stay tuned for details in the coming weeks. FSPR Lectures February & March 20 JoinPawlowski, us on Thursday, Water Sentinels February Program 20 at 7 Coordinatorpm at the Sierra for the Vista Grand Ranger Canyon District Chapter Office, of 4070the Sierra East AvenidaClub, will Saracino, Hereford, for a lecture by Becky Orozco on the Chiracahua Apache. Then, on March 20, Steve discuss ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River; current threats; and the conservation work of the Sentinels within SPRNCA. Learn how to use citizen science, “hands-on” conservation, and advocacy to shape a more-sustainable future for one of the Southwest’s most ecologically significant rivers. Second Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival March 13 & 14 The Friends have been invited to host our second Wild & Scenic Film Festival as part of the 12th annual event that showcases North America’s premier collection of short films on the environment. We have selected 13 films for the evening program for adults that are relevant to many of the issues facing the Southwest. Some will make you smile, some may get you angry, others will have you amazed, but hopefully, all will motivate you to get involved. -

OFO Ontb-Aug2010 .Qxp

ONTARIO BIRDS ONTARIO VOLUME34 NUMBER2 ONTARIO AUGUST 2016 Celebrating our th BIRDS Issue100 100 TH ISSUE VOLUME 34 NUMBER 2VOLUME 2016 AUGUST JOURNAL OF THE ONTARIO FIELD ORNITHOLOGISTS Ontario Field Ornithologists (OFO) ONTARIO is dedicated to the study of birdlife in Ontario OFO was formed in 1982 to unify the ever-growing numbers of field ornithologists (birders/birdwatchers) across the prov ince, and to pro- vide a forum for the exchange of ideas and information among its BIRDS Editors: The aim of Ontario Birds is to provide a members. Chip Weseloh, 1391 Mount Pleasant Road, veh icle for documentation of the birds of Toronto, Ontario M4N 2T7 Ont ario. We encourage the submission of full The Ontario Field Ornitho lo gists officially oversees the activities length articles and short notes on the status, Ken Abraham, 434 Manorhill Avenue, distribution, identification, and be hav iour of of the Ontario Bird Records Committee (OBRC); publishes a Peterborough, Ontario K9J 6H8 newsletter (OFO News) and this journal (Ont ar io Birds); oper ates a birds in Ont ario, as well as location guides to Chris Risley, 510 Gilmour Street, significant Ont ario bird wat ching areas, and bird sightings listserv (ONTBIRDS), coor dinated by Mark Cranford; Peterborough, Ontario K9H 2J9 similar material of interest on Ontario birds. hosts field trips throughout Ontario; and holds an Annual Conven- Associate Editor: Alan Wormington, tion and Ban quet in the autumn. Current information on all OFO R.R. #1, Leamington, Ontario N8H 3V4. Submit material for publication by e-mail attach ment (or CD or DVD) to either: activities is on the OFO website (www.ofo.ca), coordinated by Doug Copy Editor – Tina Knezevic [email protected] Woods. -

The Big Year Ebook Free Download

THE BIG YEAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Obmascik | 320 pages | 08 Dec 2011 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780857500694 | English | London, United Kingdom The Big Year PDF Book Pete Shackelford Steve Darling Archived from the original on January 26, In , Nicole Koeltzow reached the species milestone on July 1, while in August Gaylee and Richard Dean became the first birders to reach species in consecutive years. Highway runs along the California Coast. Crazy Credits. By Noah Strycker July 26, Stu is hiking with his toddler grandson already enamored by birds in the Rockies. Mary Swit Calum Worthy Miller Greg Miller It also replaces Jack Black's narration of the story with a new narration by John Cleese who also receives a credit in the opening title sequence. Narrator voice Jack Black Brad is a skilled birder who can identify nearly any species solely by sound. Category:Birds and humans Zoomusicology. Added to Watchlist. Retrieved January 25, Get Audubon in Your Inbox Let us send you the latest in bird and conservation news. Retrieved Jessica Steve Martin Paul Lavigne Heather Osborne Share this page:. Birds class : Aves. Yukon News. Tony Cindy Busby Wheel of Fortune Underscore. Visit our What to Watch page. Caprimulgiformes nightjars and relatives Steatornithiformes Podargiformes Apodiformes swifts and hummingbirds. In , an unprecedented four birders attempted simultaneous ABA Area big years. Steve's character provides fatherly guidance and support that helps Jack Black's character move forward with his life and relationships. The company is in the middle of complicated negotiations to merge with a competitor, so his two anointed successors keep calling him back to New York for important meetings; to some extent he is a prisoner of his own success. -

Hummerbird Celebration: the Big Year

For Immediate Release Contact: Sandy Jumper Vice President of Marketing and Promotion Rockport-Fulton Chamber of Commerce [email protected] (361) 729.6445 HummerBird Celebration: The Big Year An event celebrating the spectacular fall migration of hummingbirds Rockport-Fulton, Texas Celebrate the Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and all fall migrants at the 31st Annual HummerBird Celebration in Rockport and Fulton, Texas, Thursday - Sunday September 19-22. At 5 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 19, attendees will be treated to a Welcome Reception at the Rockport Center for the Arts building located at 101 S. Austin St. in Downtown Rockport. It is free to all attendees. It features wine, cheese, fine art and information on the event. The opening dinner will be a Texas Style Barbecue at the newly remodeled Saltwater Pavilion of Rockport Beach from 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. This is a ticketed event. Over the three-day event period, event attendees have an array of activities to experience. The choices include: guided bus trips to see the hummingbirds, boat and nature tours, photography talks, field trips guided by experts, lectures from world renowned speakers, workshops, outdoor exhibits and two Hummer Malls filled with vendors marketing nature-related products. Each day is filled with something special such as the Opening Texas Barbecue Dinner on Thursday, Sept. 19, featuring local birder of the year Martha McLeod and Niharika Raiput, a wildlife and conservation artist from New Delhi, India. Friday's highlight is the live bird talk given by representatives from Sky King Falconry out of San Antonio. Saturday begins with a unique Hummer Breakfast on the grounds of the History Center of Aransas County, and ends with the keynote presentation from Greg Miller, a world renowned birder whose character was played by Hollywood actor, Jack Black in the movie "The Big Year". -

PPCO Twist System

PHOTO SALON The Next Big Thing Laura Keene's Photographic Big Year ig-list birding is one of the ABA’s oldest and most storied traditions. There are shelves of books, not to mention a major motion picture, chronicling the stories of ABA Area Big Years, as well as inter- national efforts. Roger Tory Peterson and James Fisher’s 1954 Big Year continues to thrill us, and, as Kenn BKaufman has noted, Lynds Jones and pals were doing Big Days as long ago as the late 19th century. At first blush, the Big Year seems easy. What’s the Big Deal? You spend a year traveling all over the place looking at birds. But once you get to reading about Big Years, or attempting your own, certain themes begin to emerge: surprisingly complex strategies, frustration and loneliness, real hardship and sometimes outright danger, strained relationships… The central challenge of a Big Year is seeing or hearing all the species well enough to be able to say for certain that they belong on your checklist. Talk to any of the guides who have worked with Big Year birders over the years—from Attu to Florida and now Hawaii—and eventually you’ll get a little smile and an eye roll when discussing whether this or that birder actually saw this or that bird. It comes with the ter- ritory. Our lists are our own, and whether we’ve had a “good enough look” is up to each birder. Which is where Laura Keene’s unprecedented 2016 effort comes in. During her 2016 ABA Area Big Year, Laura saw 815 species—and physically documented 802 of them. -

The Evolutionary History of Birds

April, 2011 The Evolutionary History of Birds Birds are charismatic and familiar parts of our natural world, and their fossil past is equally eloquent and well documented. We will explore the gradual transition from the Raptors of Jurassic Park to the chickens and chickadees we know today. Our speaker is Brian Davis a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma. He is a native Oklahoman who grew up back east and went to school at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. He has a Masters in Zoology from the University of Oklahoma, and will be defending his dissertation and completing his PhD next month on the evolution of early fossil mammals. He became interested in birds only recently, after reading "The Big Year" in 2007. His wife is also a graduate student, They have two boys: Ben, 4, can identify more birds than the average undergraduate, and Owen, 2, will hopefully be right on his heels. Come join us and bring a friend for a good evening of camaraderie, birds, & great refreshments. Our meetings are held September through June on the third Monday of each month. Meetings begin at 7 p.m. at the Will Rogers Garden Center, I-4 and NW 36th Street. Visitors are always welcome. Cookie Patrol Refreshments for the April meeting will be provided by Bill Diffin, Nealand Hill, Marion Homier & John Cleal. Have you overlooked paying your 2011 dues??? It‟s not too late but please renew soon before your membership lapses! Dues for 2011 are $15 and can be paid at the April meeting. -

President's Message

BIRD SONGS Newsletter of the Discovery Center Bird Club August, 2012 Vol. 9, No. 1 David Foster, Editor [email protected] Officers John Randolph, President David Foster, Secretary Carne Andrews, Treasurer Jim Krakowski, Program Chair Linda Dunn, Membership President’s Message By John Randolph outstanding in-house, volunteer guide) arranged for a trip to Wyalusing State Park and adjacent Our birding hikes and adventures have always areas. This trip was guided by a young man who been greatly enjoyable to me, and this year the did a terrific job, helping us to see several Club Bird Club has further increased our opportunities life birds, such as the Kentucky Warbler, by hiring very knowledgeable guides for several Prothonotary Warbler, and my favorite sighting, of the trips taken thus far in 2012. In addition to the Cerulean Warbler, and many other species. I the wonderful skills (and generous sharing of had a particularly good look at the beautiful blue expertise) of many of our members, we benefited color of the Cerulean, despite the tree-top height from the talents of fine birders who had valuable of its perch. familiarity with the areas we visited. Starting in February in Duluth and the Sax-Zim Bog, we Although attendance was smaller than we hoped added two life birds for the Club, the relatively for, the 2012 Birding Festival was a major huge Great Black-backed Gull (biggest gull in the pleasure, with quite nice weather, good field trips, world) and the Thayer’s Gull, and got good looks and notably fine speakers and programs. -

The Big Year: a Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition the Big Year (The Movie)

The Big Year, the book and movie about the 365 day marathon of birdwatching, to find and identify an extraordinary 745 different species of birds by official year-end count. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0036QVOHS/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?ie=UTF8&btkr=1 The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition Every year on January 1, a quirky crowd of adventurers storms out across North America for a spectacularly competitive event called a Big Year -- a grand, grueling, expensive, and occasionally vicious, "extreme" 365-day marathon of birdwatching. For three men in particular, 1998 would be a whirlwind, a winner-takes-nothing battle for a new North American birding record. In frenetic pilgrimages for once-in-a-lifetime rarities that can make or break their lead, the birders race each other from Del Rio, Texas, in search of the rufous-capped warbler, to Gibsons, British Columbia, on a quest for Xantus's hummingbird, to Cape May, New Jersey, seeking the offshore great skua. Bouncing from coast to coast on their potholed road to glory, they brave broiling deserts, roiling oceans, bug-infested swamps, a charge by a disgruntled mountain lion, and some of the lumpiest motel mattresses known to man. The unprecedented year of beat-the-clock adventures ultimately leads one man to a new record -- one so gigantic that it is unlikely ever to be bested...finding and identifying an extraordinary 745 different species by official year-end count. Prize-winning journalist Mark Obmascik creates a rollicking, dazzling narrative of the 275,000-mile odyssey of these three obsessives as they fight to the finish to claim the title in the greatest -- or maybe the worst -- birding contest of all time.