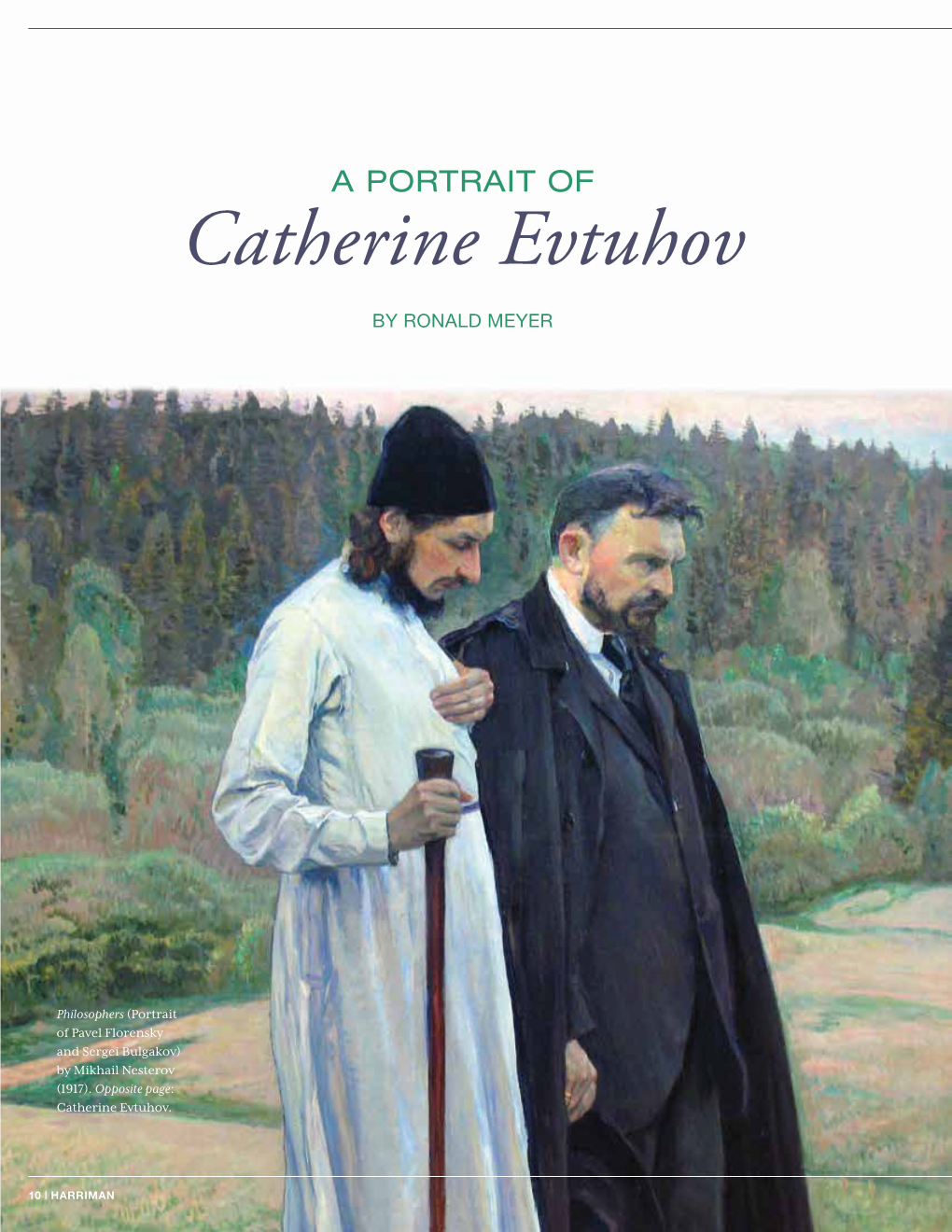

A PORTRAIT of Catherine Evtuhov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks The Johns Hopkins University Christina Lodder University of Kent VOLUME 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Utopian Reality Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond Edited by Christina Lodder Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva LEIDEn • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Staircase in the residential building for members of the Cheka (the Secret Police), Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), 1929–1936, designed by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arsenii Tumbasov. Photograph Richard Pare. © Richard Pare. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Utopian reality : reconstructing culture in revolutionary Russia and beyond / edited by Christina Lodder, Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva. pages cm. — (Russian history and culture, ISSN 1877-7791; volume 14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26320-8 (hardback : acid-free paper)—ISBN 978-90-04-26322-2 (e-book) 1. Soviet Union—Intellectual life—1917–1970. 2. Utopias—Soviet Union—History. 3. Utopias in literature. 4. Utopias in art. 5. Arts, Soviet—History. 6. Avant-garde (Aesthetics)—Soviet Union—History. 7. Cultural pluralism—Soviet Union—History. 8. Visual communication— Soviet Union—History. 9. Politics and culture—Soviet Union—History 10. Soviet Union— Politics and government—1917–1936. I. Lodder, Christina, 1948– II. Kokkori, Maria. III. Mileeva, Maria. DK266.4.U86 2013 947.084–dc23 2013034913 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. -

International Scholarly Conference the PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION of ART EXHIBITIONS. on the 150TH ANNIVERSARY of the FOUNDATION

International scholarly conference THE PEREDVIZHNIKI ASSOCIATION OF ART EXHIBITIONS. ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION ABSTRACTS 19th May, Wednesday, morning session Tatyana YUDENKOVA State Tretyakov Gallery; Research Institute of Theory and History of Fine Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow Peredvizhniki: Between Creative Freedom and Commercial Benefit The fate of Russian art in the second half of the 19th century was inevitably associated with an outstanding artistic phenomenon that went down in the history of Russian culture under the name of Peredvizhniki movement. As the movement took shape and matured, the Peredvizhniki became undisputed leaders in the development of art. They quickly gained the public’s affection and took an important place in Russia’s cultural life. Russian art is deeply indebted to the Peredvizhniki for discovering new themes and subjects, developing critical genre painting, and for their achievements in psychological portrait painting. The Peredvizhniki changed people’s attitude to Russian national landscape, and made them take a fresh look at the course of Russian history. Their critical insight in contemporary events acquired a completely new quality. Touching on painful and challenging top-of-the agenda issues, they did not forget about eternal values, guessing the existential meaning behind everyday details, and seeing archetypal importance in current-day matters. Their best paintings made up the national art school and in many ways contributed to shaping the national identity. The Peredvizhniki -

The Art of Printing and the Culture of the Art Periodical in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917)

University of Alberta The Art of Printing and the Culture of the Art Periodical in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917) by Hanna Chuchvaha A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Modern Languages and Cultural Studies Art and Design ©Hanna Chuchvaha Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. To my father, Anatolii Sviridenok, a devoted Academician for 50 years ABSTRACT This interdisciplinary dissertation explores the World of Art (Mir Iskusstva, 1899- 1904), The Golden Fleece (Zolotoe runo, 1906-1909) and Apollo (Apollon, 1909- 1917), three art periodicals that became symbols of the print revival and Europeanization in late Imperial Russia. Preoccupied with high quality art reproduction and graphic design, these journals were conceived and executed as art objects and examples of fine book craftsmanship, concerned with the physical form and appearance of the periodical as such. Their publication advanced Russian book art and stimulated the development of graphic design, giving it a status comparable to that of painting or sculpture. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Paul Kulikovsky №83 February 2015 Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich - Portrait by Konstantin Gorbunov, 2015 In memory of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich It was quite amazing how many events was held this year in commemoration of the assassination of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich - 110 years ago - on 17th of February 1905. Ludmila and I went to the main event, which was held in Novospassky Monastery, were after the Divine liturgy, was held a memorial service for Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, who is buried there in the crypt of the Romanov Boyars. The service in the church of St. Romanos the melodist (in the crypt of the Romanov Boyars) was led by Bishop Sava and Bishop Photios Nyaganskaya Ugra and concelebrated by clergy of Moscow. The service was attended by Presidential Envoy to the Central Federal District A.D. Beglov, Chairman of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society S.V. Stepashin, chairman of the Moscow City Duma A.V. Shaposhnikov, President of Elisabeth Sergius Educational Society Anna V. Gromova, Grand Duke George Michailovich and Olga Nicholaievna Kulikovsky-Romanoff, Ludmila and Paul Kulikovsky, Director of Russian State Archives S. V. Mironenko, and members of the Russian Nobility Assembly. Present were also the icon of Mother of God "Quick to Hearken" to which members of the Romanov family were praying, and later residents of besieged Leningrad. It had arrived a few days earlier from the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg. The Mother of God is depicted on it without the baby, praying with outstretched right hand. -

The Soil of Radonezh and the Artists of Abramtsevo

Experiment 25 (2019) 83-100 brill.com/expt The Soil of Radonezh and the Artists of Abramtsevo Inge Wierda Lecturer in Art History at Wackers Academie, Amsterdam, Boulevard Magenta, Laag-Soeren, and HOVO University of Utrecht Editor-in-chief of Eikonikon: Journal of Icons [email protected] Abstract This article examines the historical and spiritual significance of Radonezh soil and its impact on the artistic practice of the Abramtsevo circle. Through a close reading of three paintings—Viktor Vasnetsov’s Saint Sergius of Radonezh (1881) and Alenushka (1881), and Elena Polenova’s Pokrov Mother of God (1883)—it analyzes how the Abramtsevo artists negotiated Saint Sergius’s legacy alongside their own experiences of the sacred sites in this area and especially the Pokrovskii churches. These artworks demonstrate how, in line with the prevalent nineteenth-century Slavophile interests, Radonezh soil provided a fertile ground for articulating a distinct Russian Orthodox identity in the visual arts of the 1880s and continues to inspire artists to this day. Keywords Abramtsevo – Khotkovo – Akhtyrka – Sergiev Posad – Elena Polenova – Viktor Vasnetsov – Saint Sergius – Pokrov Mother of God – Intercession – Alenushka – Icon of the Akhtyrka Mother of God – Trinity From July 16 to October 10, 2014, the Federal State Cultural Establishment Artistic and Literary Museum-Reserve Abramtsevo organized the exhibition “By the Pokrovskii Convent. Artists of Radonezh Soil.” Local artists such as Iulia Goncharova, Oleg Lieven, and Aleksandr Petrov celebrated the -

The Peredvizhniki Pioneers of Russian Painting

Inessa Kouteinikova exhibition review of The Peredvizhniki Pioneers of Russian Painting Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) Citation: Inessa Kouteinikova, exhibition review of “The Peredvizhniki Pioneers of Russian Painting,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn12/kouteinikova-reviews-the-peredvizhniki. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Kouteinikova: The Peredvizhniki Pioneers of Russian Painting Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012) The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting The National Museum, Stockholm Sweden September 29, 2011 – January 22, 2012 Kunstsammlung Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany February 26, 2012 – May 28, 2012 Catalogue: The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting. Edited by David Jackson and Per Hedström. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum and Elanders Falth & Hassler, Varnamo 2011. 303 pp; color illustrations. $89.95 (hardcover) ISBN: 9789171008312 (English) ISBN: 9789171008305 (Swedish) On November 9, 1863 art students protested against the subject prescribed for the annual Gold Medal painting competition at the Imperial Art Academy in St Petersburg, Russia; as a result, fourteen of the best artists left the school.[1] Among them were Ivan Kramskoy, Konstantin Makovsky, Aleksej Korzukhin, and Nikoaj Shustov. Those who remained behind did so in order to pursue the goal of receiving the Gold Medal, the highest academic award for young artists in imperial Russia. In addition to the medal, the winning recipient was granted an opportunity to study in Italy for up to three years. -

The State Tretyakov Gallery the State Tretyakov Gallery Is a Museum of Russian Art

1. Read the passage and answer the questions: What is the passage about? Pavel Tretyakov is an outstanding person in Russian culture. He was not only a collector, but a patron of the arts as well. He was interested in paiting, followed the development of art, believed in Russian artists and rejoiced at their success. Pavel Tretyakov decided to collect the most talented works of Russian realistic painters. The artists appreciated his attempt to turn his collection into a national gallery and helped him to do that. Pavel Tretyakov started with the pictures of his contemporaries and later began to collect pieces What is the Tretyakov Gallery famous of ancient art as well. By the 1870s his collection was for? opened for the public. The State Tretyakov Gallery The State Tretyakov Gallery is a museum of Russian art. It is one of the largest museums in the world. The Tretyakov Gallery was founded by Pavel Tretyakov (1832-1898) in the middle of the 19th century. In 1856 Pavel Tretyakov bought his first two paintings: “Temptation” by Shilder and “Skirmish with Finnish Smugglers” by Khudyakov. This year is considered to be the date of the foundation of the Tretyakov Gallery. Pavel Tretyakov is an outstanding person in Russian culture. He was not only a collector, but a patron of the arts as well. He was interested in painting, followed the development of art, believed in Russian artists and rejoiced at their success. Pavel Tretyakov decided to collect the most talented works of Russian realistic painters. The artists appreciated his attempt to turn his collection into a national gallery and helped him to do that. -

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives EDITED BY LOUISE HARDIMAN AND NICOLA KOZICHAROW To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives Edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Copyright of each chapter is maintained by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Mikhail Vrubel and the Search for a Modernist Idiom

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives EDITED BY LOUISE HARDIMAN AND NICOLA KOZICHAROW https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Copyright of each chapter is maintained by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. The publication of this volume has been made possible by a grant from the Scouloudi Foundation in association with the Institute of Historical Research at the School of Advanced Study, University of London. -

Romantic Nationalism and the Image of the Bird-Human in Russian Art of the 19Th and Early 20Th Century

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Romantic Nationalism and the Image of the Bird-Human in Russian Art of the 19th and early 20th Century Kathleen Diane Keating Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Painting Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Keating, Kathleen Diane, "Romantic Nationalism and the Image of the Bird-Human in Russian Art of the 19th and early 20th Century" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 285. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/285 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romantic Nationalism and the Image of the Bird-Human in Russian Art of the 19th and early 20th Century A Senior Project by Kathleen Keating for the program of Russian and Eurasian Studies at Bard College, May 4th, 2016 Acknowledgements ТО Oleg Minin, my advisor, -

On the Format of the Divine

Legal proceedings, sermons, and the creative industries; the universal applicability of law, the consensus of the flock, and corporate ethics. All of them require that you forget or repress something, that you pay a price for the (im)possibility of joining the fold. But what if you are in a court of law, or maybe listening to a 01/06 sermon, or sitting at an office, and you can’t afford the fee? You start to suspect that the silent majority around you has already paid up, that they have become one with the laws of the state, God, or commerce, and this stirs your soul with anarchist protest: your imagination calls for riot and transgression. You want to subvert the serenity of all those present, all those who agree. Gleb Napreenko ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ“There is so much of the repressed in this painting,” Sasha Novozhenova told me in front of The Venerable Sergei in His Youth, at an On the Format exhibition by Mikhail Nesterov1 in the Tretyakov Gallery: a scrofulous lad in a monk’s habit once of the Divine again rolls his eyes ecstatically in the midst of Russian Nature, nothing but a frail vessel for the grace of God to fill his pretty boy’s body, as he waits with pale, clammy palms É It’s better to stop here, lest we give rise to too copious a stream of perverted fantasies and garbled fragments of the returning repressed: sex, femininity, and violence. It isn’t very hard to poke fun at Nesterov’s religious masterpieces at the exhibition “In Search of My Russia,” just like it isn’t hard to poke fun at Tikhon Shevkunov, the shifty archimandrite rumored to be Putin’s spiritual mentor.