The Konami Code: an Experiment in Dialect Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry Aerospace • KAWASAKI • VOLVO • CATERPILLAR • ADVANCED COATING • KEDDEG COMPANY • XI'AN AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY • CHINA FAW GROUP TECHNOLOGIES GROUP • KOREAN AIRLINES • CHINA INTERNATIONAL Agriculture • AIRBUS MARINE CONTAINERS • L3 COMMUNICATIONS • AIRCELLE • AGRICOLA FORNACE • CHRYSLER • LOCKHEED MARTIN • ALLIANT TECHSYSTEMS • CARGILL • COMMERCIAL VEHICLE • M7 AEROSPACE GROUP • AVICHINA • E. RITTER & COMPANY • • MESSIER-BUGATTI- CONTINENTAL AIRLINES • BAE SYSTEMS • EXOPLAST DOWTY • CONTINENTAL • BE AEROSPACE • MITSUBISHI HEAVY • JOHN DEERE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES • • BELL HELICOPTER • MAUI PINEAPPLE CONTINENTAL • NASA COMPANY AUTOMOTIVE SYSTEMS • BOMBARDIER • • NGC INTEGRATED • USDA COOPER-STANDARD • CAE SYSTEMS AUTOMOTIVE Automotive • • CORNING • CESSNA AIRCRAFT NORTHROP GRUMMAN • AGCO • COMPANY • PRECISION CASTPARTS COSMA INDUSTRIAL DO • COBHAM CORP. • ALLIED SPECIALTY BRASIL • VEHICLES • CRP INDUSTRIES • COMAC RAYTHEON • AMSTED INDUSTRIES • • CUMMINS • DANAHER RAYTHEON E-SYSTEMS • ANHUI JIANGHUAI • • DAF TRUCKS • DASSAULT AVIATION RAYTHEON MISSLE AUTOMOBILE SYSTEMS COMPANY • • ARVINMERITOR DAIHATSU MOTOR • EATON • RAYTHEON NCS • • ASHOK LEYLAND DAIMLER • EMBRAER • RAYTHEON RMS • • ATC LOGISTICS & DALPHI METAL ESPANA • EUROPEAN AERONAUTIC • ROLLS-ROYCE DEFENCE AND SPACE ELECTRONICS • DANA HOLDING COMPANY • ROTORCRAFT • AUDI CORPORATION • FINMECCANICA ENTERPRISES • • AUTOZONE DANA INDÚSTRIAS • SAAB • FLIR SYSTEMS • • BAE SYSTEMS DELPHI • SMITH'S DETECTION • FUJI • • BECK/ARNLEY DENSO CORPORATION -

Factset-Top Ten-0521.Xlsm

Pax International Sustainable Economy Fund USD 7/31/2021 Port. Ending Market Value Portfolio Weight ASML Holding NV 34,391,879.94 4.3 Roche Holding Ltd 28,162,840.25 3.5 Novo Nordisk A/S Class B 17,719,993.74 2.2 SAP SE 17,154,858.23 2.1 AstraZeneca PLC 15,759,939.73 2.0 Unilever PLC 13,234,315.16 1.7 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,046,820.57 1.6 L'Oreal SA 10,415,009.32 1.3 Schneider Electric SE 10,269,506.68 1.3 GlaxoSmithKline plc 9,942,271.59 1.2 Allianz SE 9,890,811.85 1.2 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd. 9,477,680.83 1.2 Lonza Group AG 9,369,993.95 1.2 RELX PLC 9,269,729.12 1.2 BNP Paribas SA Class A 8,824,299.39 1.1 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. 8,557,780.88 1.1 Air Liquide SA 8,445,618.28 1.1 KDDI Corporation 7,560,223.63 0.9 Recruit Holdings Co., Ltd. 7,424,282.72 0.9 HOYA CORPORATION 7,295,471.27 0.9 ABB Ltd. 7,293,350.84 0.9 BASF SE 7,257,816.71 0.9 Tokyo Electron Ltd. 7,049,583.59 0.9 Munich Reinsurance Company 7,019,776.96 0.9 ASSA ABLOY AB Class B 6,982,707.69 0.9 Vestas Wind Systems A/S 6,965,518.08 0.9 Merck KGaA 6,868,081.50 0.9 Iberdrola SA 6,581,084.07 0.8 Compagnie Generale des Etablissements Michelin SCA 6,555,056.14 0.8 Straumann Holding AG 6,480,282.66 0.8 Atlas Copco AB Class B 6,194,910.19 0.8 Deutsche Boerse AG 6,186,305.10 0.8 UPM-Kymmene Oyj 5,956,283.07 0.7 Deutsche Post AG 5,851,177.11 0.7 Enel SpA 5,808,234.13 0.7 AXA SA 5,790,969.55 0.7 Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Notification of Business Conducted at the 41St Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders

NOTIFICATION OF BUSINESS CONDUCTED AT THE 41ST ORDINARY GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS Stock Code Number: 9766 June 27, 2013 Dear Shareholder, This is to inform you that the following reports were presented and the resolutions were passed at the 41st Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders held on June 27, 2013. Sincerely yours, Kagemasa Kozuki Representative Director KONAMI CORPORATION 7-2, Akasaka 9-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo Reports 1. Business Report, Consolidated Financial Statements for the 41st fiscal year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2013); and on the Reports of the accounting auditor and of the Board of Corporate Auditors regarding Consolidated Financial Statements for the 41st fiscal year 2. Financial Statements for the 41st fiscal year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2013) We reported the contents of the above. Resolutions Proposal 1: Election of seven members to the Board of Directors It was approved as proposed. Messrs. Kagemasa Kozuki, Takuya Kozuki, Kimihiko Higashio, Noriaki Yamaguchi, Tomokazu Godai, Hiroyuki Mizuno and Akira Gemma were reelected and reassumed their office as Director. Proposal 2: Election of two members to the Board of Corporate Auditors It was approved as proposed. Messrs. Shinichi Furukawa and Minoru Maruoka were newly elected and assumed their office as Corporate Auditor. Proposal 3: Continuation and Partial Revision of the Countermeasures to Large-Scale Acquisitions of KONAMI CORPORATION Shares (takeover defense measures) It was approved as proposed. As a result of resolutions passed at the meetings of the Board of Directors and the Board of Corporate Auditors which were held after the 41st Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders, the new Board of Directors and Board of Corporate Auditors as of June 27, 2013, are set as shown on the following page. -

Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Introduces Playstation®4 (Ps4™)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SONY COMPUTER ENTERTAINMENT INC. INTRODUCES PLAYSTATION®4 (PS4™) PS4’s Powerful System Architecture, Social Integration and Intelligent Personalization, Combined with PlayStation Network with Cloud Technology, Delivers Breakthrough Gaming Experiences and Completely New Ways to Play New York City, New York, February 20, 2013 –Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) today introduced PlayStation®4 (PS4™), its next generation computer entertainment system that redefines rich and immersive gameplay with powerful graphics and speed, intelligent personalization, deeply integrated social capabilities, and innovative second-screen features. Combined with PlayStation®Network with cloud technology, PS4 offers an expansive gaming ecosystem that is centered on gamers, enabling them to play when, where and how they want. PS4 will be available this holiday season. Gamer Focused, Developer Inspired PS4 was designed from the ground up to ensure that the very best games and the most immersive experiences reach PlayStation gamers. PS4 accomplishes this by enabling the greatest game developers in the world to unlock their creativity and push the boundaries of play through a system that is tuned specifically to their needs. PS4 also fluidly connects players to the larger world of experiences offered by PlayStation, across the console and mobile spaces, and PlayStation® Network (PSN). The PS4 system architecture is distinguished by its high performance and ease of development. PS4 is centered around a powerful custom chip that contains eight x86-64 cores and a state of the art graphics processor. The Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) has been enhanced in a number of ways, principally to allow for easier use of the GPU for general purpose computing (GPGPU) such as physics simulation. -

Provista, Our Company's Supply Chain Partner, Offers You Personal

The best savings on the best products — only for you at Best Buy.® Provista, our company’s supply chain partner, offers you personal discounts on more than 150,000 brand-name products in addition to a complete in-store selection. Enjoy huge savings on products like: • HD displays • Tablets • Video games • Laptops • Printers • Appliances Get started by signing up. You’ll need: Steps to create an account: 1) Your company 1) Visit bbfb.com/psf/provista Member ID 2) Click on the right 2) The Best Buy Registration side of the screen code: PROVISTA1 3) Complete the form as directed 4) Click at the bottom of the page 5) Enjoy the website! Need assistance with your member ID or have other questions? Call Provista at 888-538-4662 © 2015 Provista Empower your business with a powerful product line. Appliances Denon (Boston Acoustics) Fūl Philips Dynex Anaheim Griffin Technology Gefen Pioneer Electronics Elmo Aroma iHome (Hotel Golla Plantronics Fuji Avanti Technologies) Harman Multimedia RCA GoPro Bissell Insignia HP Roku Labs HP Black & Decker Ion Audio Incase Russound Insignia Bosch Klipsch Init Samsung JVC Broan LG Electronics Insignia Sennheiser Kingston Bunn Logitech Kensington Sharp Kodak Char-Broil Monster Cable Klipsch Shure Lenmar Conair Numark Lenovo Sirius Lexar Cuisinart Panasonic Logitech Sony Lite-On Danby Peavey Electronics Macally Toshiba Logitech DeLonghi Peerless Industries Microsoft Universal Electronics Lowepro Dirt Devil Philips NLU Products ViewSonic Microsoft Dyson Pioneer Electronics Peerless Industries XM Nikon Electrolux -

RAJ RAMAYYA Composer for Film, Television & Games

RAJ RAMAYYA composer for film, television & games Contact: ARI WISE, agent • 1.866.784.3222 • [email protected] FEATURE FILM WOLF’S RAIN (Anime Feature – Original Songs) 2003 Go Haruna, Minoru Takanashi, prod. Bendai Visual Co., Bones, Fuji Television Network COWBOY BEBOP (Anime Feature – Original Songs) 2001 Ryohei Tsunoda, Takayuki Yoshii, , prod. Destination Films/Sony Pictures Entertainment Shinichiro Watanabe, dir. CHIN CHIRO MAI (original songs) 2000 Kazuhiko Kato, prod. Sony Music Entertainment TELEVISION/DOCUMENTARY SHADOW OF DUMONT (Documentary) 2020 Kelly Balon, Anand Ramayya, prod. Karma Film, Vision Tevor Cameron, dir. WHO KILLED GANDHI? (Documentary) 2013 Kelly Balon, Anand Ramayya, prod. Karma Film, Vision/Zoomer Television Anand Ramayya, dir. PATHS OF PILGRIMS (Documentary) 2013 Marilyn Thomas, prod. Monkey Ink Media Kate Kroll, dir. LITTLE CHARO (Series) 2010 Y. Takayanagi, Jako Mizukami, prod. NHK Japan various, dir. LANDINGS (Series) 2010 Ryan Lockwood, prod. SCN/CBC MAD COW SACRED COW (Documentary) 2009 Stephen Huszar, Ryan Lockwood, Anand Karma Film, Hulo Films, Film Option International Ramayya prod., Anand Ramayya, dir. EIGORYAN! (TV Series) 2006 K. Sato, prod. NHK Japan THE WORLD OF GOLDEN EGGS (TV Series Theme) 2005 Yoshihiko Dai, prod. PLUSheads Inc., Warner Home Video COSMIC CURRENT (Documentary) 2004 Joseph MacDonald, Graydon McCrea, prod. National Film Board of Canada Anand Ramayya, dir. GUNGRAVE-UNOS (TV Series Theme) 2004 Shigeru Kitayama, Toru Kubo, prod. Geneon Entertainment various, dir. 48 HOURS -

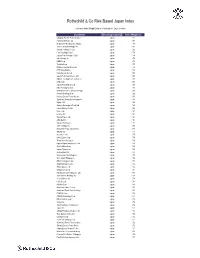

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of January 31, 2020 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight (%) Chugoku Electric Power Co Inc/ Japan 1.01 Yamada Denki Co Ltd Japan 0.91 McDonald's Holdings Co Japan L Japan 0.88 Sushiro Global Holdings Ltd Japan 0.82 Skylark Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.82 Fast Retailing Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Ain Holdings Inc Japan 0.78 KDDI Corp Japan 0.77 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.75 Mizuho Financial Group Inc Japan 0.74 NTT DOCOMO Inc Japan 0.73 Kobe Bussan Co Ltd Japan 0.72 Japan Post Insurance Co Ltd Japan 0.69 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 0.69 LINE Corp Japan 0.69 Japan Post Bank Co Ltd Japan 0.68 Nitori Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.67 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.66 Konami Holdings Corp Japan 0.66 Kyushu Electric Power Co Inc Japan 0.65 Sumitomo Realty & Development Japan 0.65 Fujitsu Ltd Japan 0.63 Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd Japan 0.63 Japan Airlines Co Ltd Japan 0.62 NEC Corp Japan 0.61 Lawson Inc Japan 0.60 Sekisui House Ltd Japan 0.60 ABC-Mart Inc Japan 0.60 Kyushu Railway Co Japan 0.60 ANA Holdings Inc Japan 0.59 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Lt Japan 0.58 ORIX Corp Japan 0.57 Secom Co Ltd Japan 0.57 Seiko Epson Corp Japan 0.56 Trend Micro Inc/Japan Japan 0.56 Nippon Paper Industries Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Suzuki Motor Corp Japan 0.56 Japan Tobacco Inc Japan 0.55 Aozora Bank Ltd Japan 0.55 Sony Financial Holdings Inc Japan 0.55 West Japan Railway Co Japan 0.54 MEIJI Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Sugi Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Tokyo -

Empower Your Business with a Powerful Product Line

Empower your business w ith a powerful product line. Appliances Denon (Boston Acoustics) Fu! Philips Dynex Anaheim Griffin Technology Gefen Pioneer Electronics Elmo iHome (Hotel Golla Plantronics Fuji Aroma Avanti Technologies) Harman Multimedia RCA Go Pro Insignia HP RokuLabs HP Bissell Black & Decker Ion Audio In case Russound Insignia Klipsch !nit Samsung JVC Bosch Broan LG Electronics Insignia Sennheiser Kingston Bunn Logitech Kensington Sharp Kodak Char-Broil Monster Cable Klipsch Shure Len mar Conair Numark Lenovo Sirius Lexar Panasonic Logitech Sony Lite-On Cuisinart Danby Peavey Electronics Macally Toshiba Logitech Peerless Industries Microsoft Universal Electronics Lowepro De Longhi Dirt Devil Philips NLU Products ViewSonic Microsoft Dyson Pioneer Electronics Peerless Industries XM Nikon Electrolux Polk Audio Plantronics Olympus Eureka Rocketfish Primax Electronics Displays Panasonic Euro-Pro Russound RCA Acer America Pen tax Frigidaire Samsung Rocketfish AOC Pinnacle SDI Technologies (iHome) Samsonite PNY GE ASUS GE Profile Sennheiser Samsung Dell Pure Digital Haier Sharp Sennheiser HP Samsung Hamilton Beach Skullcandy SIIG Lenovo San disk HoMedics So nos Sony LG Sanyo Fisher Sony Speck Sony Honeywell NEC Hoover Yamaha StarTech.com Panasonic Sunpak Yamaha Pro Audio STM Bags Targus Hotpoint Samsung Inglis Swiss Gear Sharp Toshiba Targus Vivi tar iRobot Cables Sony Keurig Cables To Go Timbuk2 Toshiba KitchenAid Belkin Toshiba View Sonic Interactive Velocity Micro Electronics Krups Dynex Whiteboards Wacom Lasko Monster Cable E-Readers -

Miki Orihara Solo Concert

LaGuardia Performing Arts Center Steven Hitt...Artistic Producing Director Handan Ozbilgin...Associate Director/Artistic Director Rough Draft Festival Carmen Griffin...Theatre Operations Manager/Technical Director Toni Foy...Education Outreach Coordinator Isabelle Marsico...Events Coordinator Caryn Campo...Finance Officer LaGuardia Performing Arts Center Mariah Sanchez...House Manager Scott Davis...Line Producer Juan Zapata...Graphic Designer Luisa Fer Alarcon...Video Editor/Designer Dayana Sanchez...Marketing Coordinator MIKI ORIHARA SOLO CONCERT Production Staff Patrick Anthony Surillo...Resident Stage Manager Cassandra Lynch...Props Master Hollis Duggans…Production Staff Works of American and Japanese Modern Dance Pioneers Winter Muniz…Production Staff Piano by Nora Izumi Bartosik Technical Staff Glenn Wilson...Stage Manager/Assistant Technical Director Melody Beal...Lighting Designer Alex Desir...Master Electrician Ronn Thomas...Sound Engineer Miki Orihara Marland Harrison...Technician Denton Bailey...Technician Giovanni Perez...Technician House Staff Marissa Bacchus Jason Berrera Julio Chabla Rachel Faria Anne Husmann Emily Johnson Martha Graham Doris Humphrey Rebecca Shrestha LaGuardia Community College Dr. Gail O. Mellow...President Dr. Paul Arcario...Provost and Senior Vice President 31-10 Thomson Avenue Long Island City, 11101 Seiko Takata Konami Ishii Yuriko Upper left: Martha Graham in Lamentation(1930) Photo by Soichi Sunami, courtesy of The Sunami Family. Upper middle: Miki Orihara, Photo by Tokio Kuniyoshi. Upper right: Doris Humphrey photo by Soichi Sunami , courtesy of the Sunami Family. Lower left: Seiko Takata(1938) in Mother Photo courtesy of Nanako Yamada. Lower middle: Konami Ishii in Koushou (1938) Photo courtesy of Noriko Sato. Lower right: Yuriko in The Cry (1963) Photo courtesy of the Kikuchi Family. WWW.LPAC.NYC RESONANCE III “Onko chishin” – is a Japanese expression describing an attempt to discover new things by studying the past. -

The Japanese Gaming Cluster

The Japanese Gaming Cluster Tatsuya Hasegawa, Takeru Ito, Ryu Kawano, Koichi Kibata, Ken Nonomura 1 Table of Contents 1. Japan Competitiveness ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Country Background ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 The Economic Performance of Japan after WW II ............................................................................ 4 1.3 Macroeconomic and Political Risks .................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Social infrastructure .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Microeconomic competitiveness and national diamond analysis ...................................................... 7 1.5.1 Context for Firm Strategy and Rivalry ....................................................................................... 8 1.5.2 Demand Condition ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.5.3 Supporting and Related Industry ................................................................................................ 8 1.5.4 Factor Condition ........................................................................................................................ 9 1.6 National Cluster mapping and industrial -

Calvert VP EAFE International Index Portfolio 1St Quarter Holdings

Calvert VP EAFE International Index Portfolio March 31, 2020 Schedule of Investments (Unaudited) Common Stocks — 98.5% Security Shares Value Australia (continued) Security Shares Value Australia — 5.8% Ramsay Health Care, Ltd. 1,442 $ 50,704 REA Group, Ltd. 537 25,155 AGL Energy, Ltd. 6,090 $ 63,734 Rio Tinto, Ltd. 3,172 163,420 Alumina, Ltd.(1) 14,501 12,996 Santos Ltd., 13,517 27,761 AMP,Ltd.(1)(2) 22,416 18,306 Scentre Group 45,895 43,959 APA Group(1) 11,361 72,094 Seek, Ltd.(1) 3,323 30,366 Aristocrat Leisure, Ltd. 4,773 61,847 Sonic Healthcare, Ltd. 4,020 60,420 ASX, Ltd. 1,623 76,185 South32, Ltd. 48,353 53,377 Aurizon Holdings, Ltd. 16,477 42,701 Stockland 19,317 29,704 AusNet Services(1) 27,031 28,383 Suncorp Group, Ltd.(1) 11,330 62,918 Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, Ltd. 24,210 253,900 Sydney Airport 8,748 30,225 Bendigo & Adelaide Bank, Ltd. 4,706 18,080 Tabcorp Holdings, Ltd.(1) 15,814 24,474 BGP Holdings PLC(2)(3) 77,172 — Telstra Corp., Ltd. 37,215 69,858 BHP Group, Ltd. 26,250 476,209 TPG Telecom, Ltd.(1) 3,460 14,735 BlueScope Steel, Ltd. 4,388 22,973 Transurban Group(1) 24,274 180,808 Boral, Ltd. 10,917 13,712 Treasury Wine Estates, Ltd. 6,449 40,039 Brambles, Ltd. 14,024 90,648 Vicinity Centres 25,959 16,238 Caltex Australia, Ltd. 1,867 25,210 Washington H. -

Stoxx True Exposure™ Japan 25% Index

STOXX TRUE EXPOSURE™ JAPAN 25% INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Toyota Motor Corp. Automobiles & Parts Japan 2.10 Softbank Group Corp. Telecommunications Japan 1.90 KDDI Corp. Telecommunications Japan 1.74 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Telecommunications Japan 1.53 Keyence Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 1.51 RECRUIT HOLDINGS Industrial Goods & Services Japan 1.46 Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd. Health Care Japan 1.39 Oriental Land Co. Ltd. Travel & Leisure Japan 1.25 Central Japan Railway Co. Travel & Leisure Japan 1.20 Sony Corp. Personal & Household Goods Japan 1.15 NTT DoCoMo Inc. Telecommunications Japan 1.15 Itochu Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 1.15 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Banks Japan 1.08 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou Banks Japan 1.05 Fast Retailing Co. Ltd. Retail Japan 0.99 East Japan Railway Co. Travel & Leisure Japan 0.94 Kao Corp. Personal & Household Goods Japan 0.89 Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Health Care Japan 0.85 Mitsubishi Estate Co. Ltd. Real Estate Japan 0.84 M3 Health Care Japan 0.82 Aeon Co. Ltd. Retail Japan 0.80 Tokio Marine Holdings Inc. Insurance Japan 0.80 Mitsubishi Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.76 Mizuho Financial Group Inc. Banks Japan 0.76 Secom Co. Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.75 SOFTBANK Telecommunications Japan 0.73 Nitori Co. Ltd. Retail Japan 0.73 Mitsui Fudosan Co. Ltd. Real Estate Japan 0.72 Shiseido Co. Ltd. Personal & Household Goods Japan 0.71 Daiwa House Industry Co. Ltd. Personal & Household Goods Japan 0.71 Fujitsu Ltd. Technology Japan 0.69 Z HOLDINGS Technology Japan 0.67 Mitsui & Co.